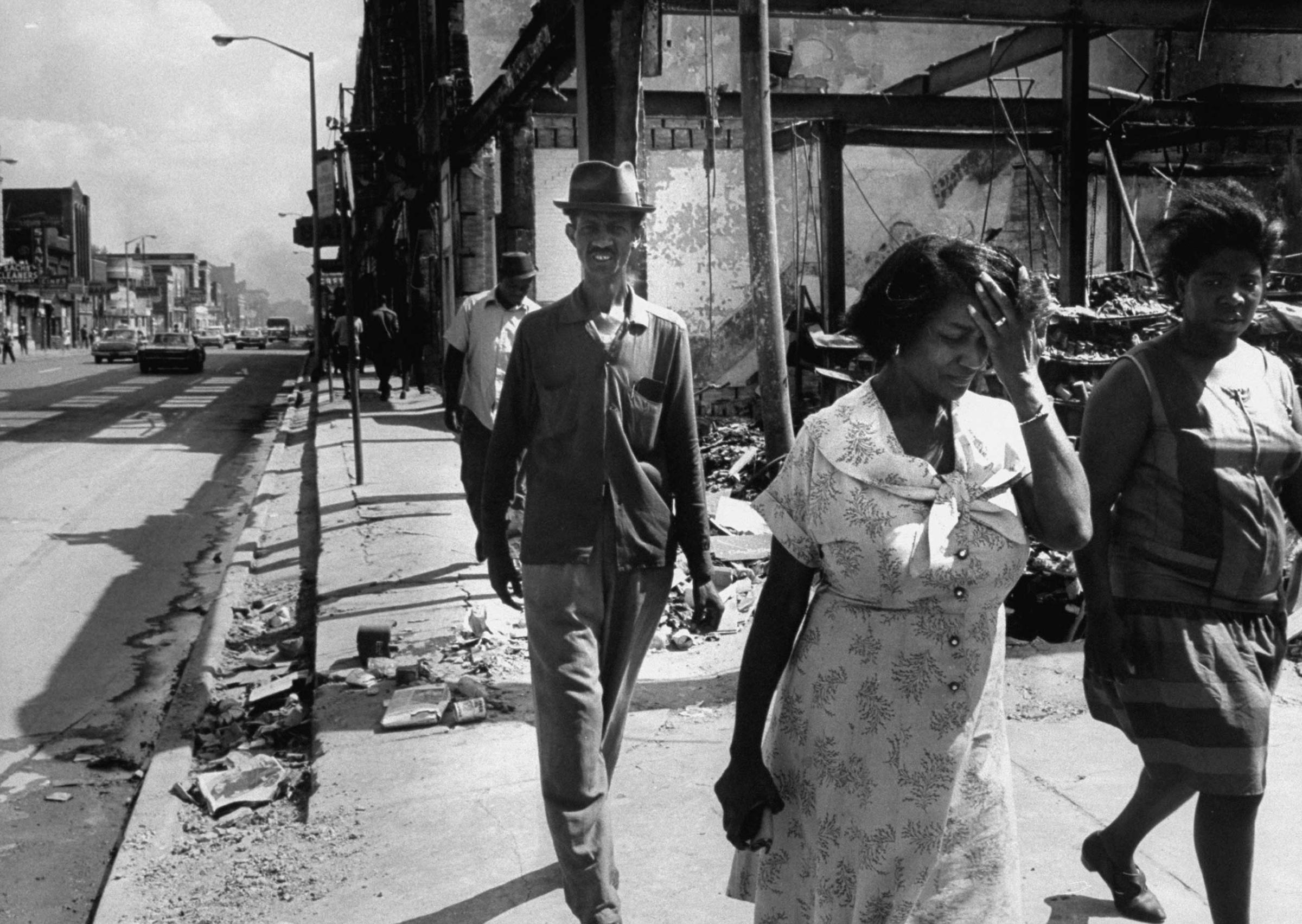

Almost exactly 50 years ago, when TIME looked for one experience with which to summon the mood of the riots that swept Detroit in the summer of 1967, the magazine turned to Hubert G. Locke, then an administrative assistant to the Detroit police commissioner and a member of the disproportionately small group of black employees of the police department. At midnight, the story explained, he “left his desk at headquarters and climbed to the roof for a look at Detroit. When he saw it, he wept. Beneath him, whole sections of the nation’s fifth largest city lay in charred, smoking ruins.”

Locke, who would go on to have a long career in academia and whose book The Detroit Riot of 1967 was recently reissued, remembers that moment well.

“At some point I simply went up after dark on the top of police headquarters, which is a 13-story building, and looked out over the city,” he recalls. “While I was not in the Second World War, Detroit looked like what I imagined Dresden looked like after its fire-bombing in World War II. You could just see flames, pockets of flames, all across the city, east and west. That was enough to be one of the saddest moments in my life, for a city that I grew up in, loved dearly and still have a passion for.”

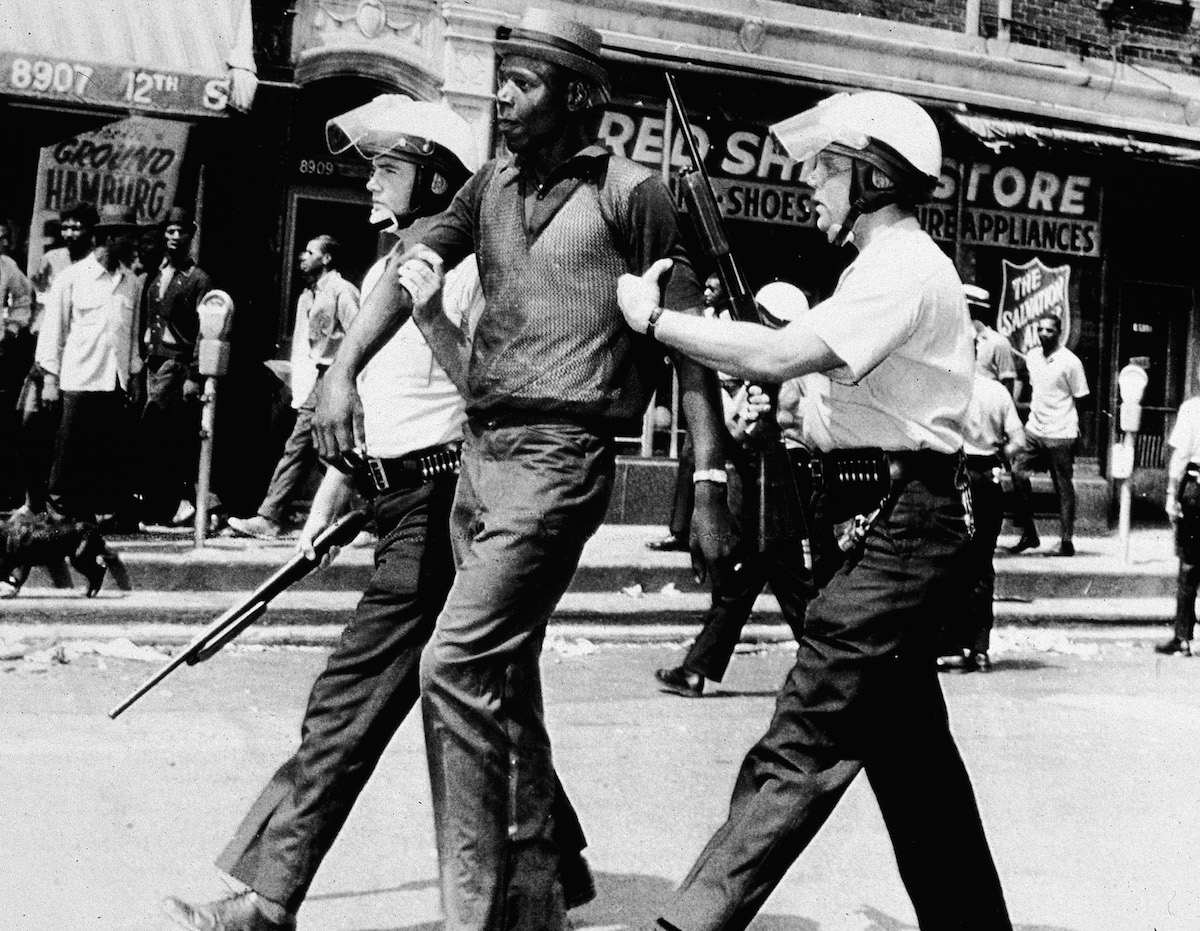

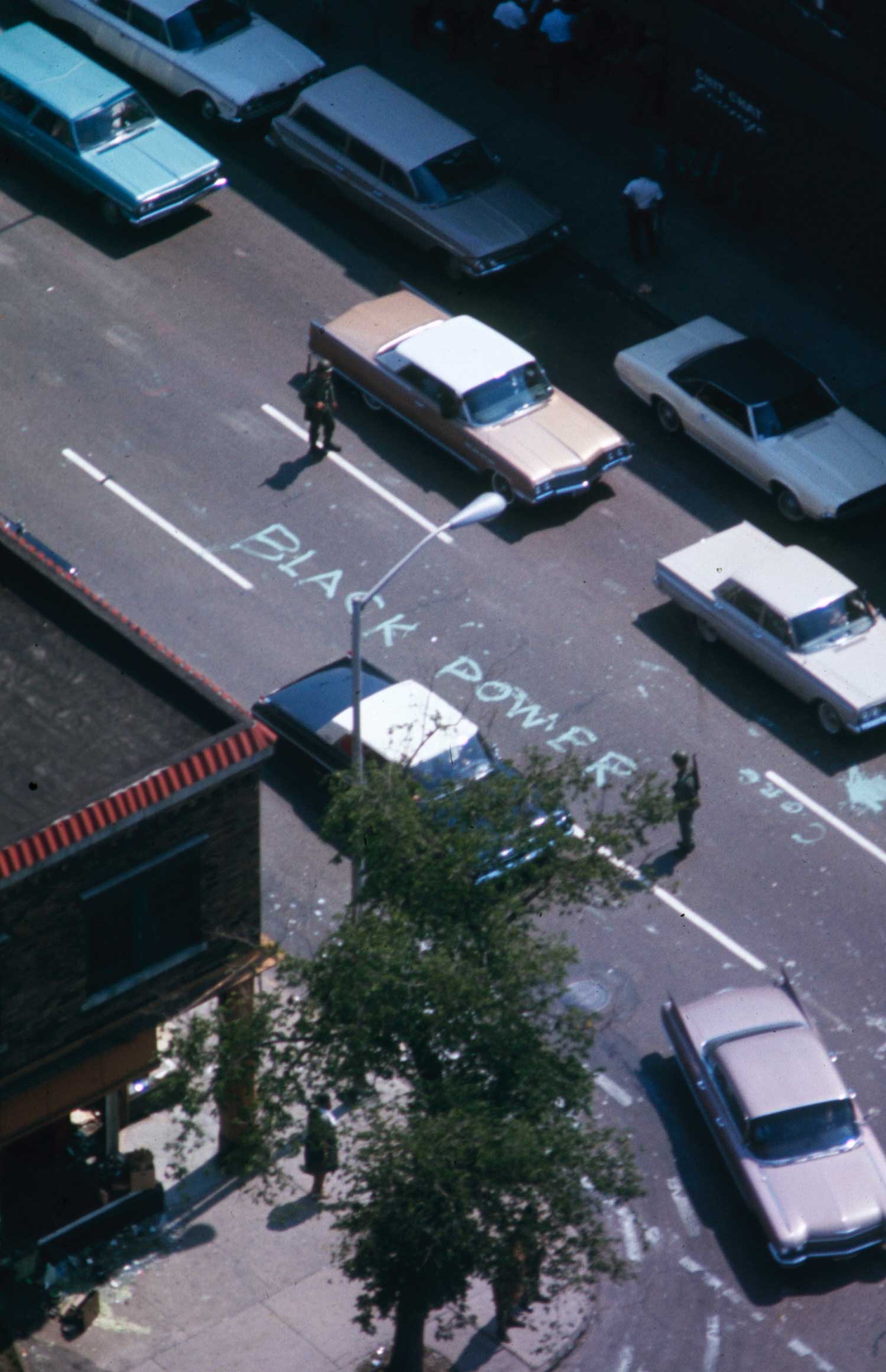

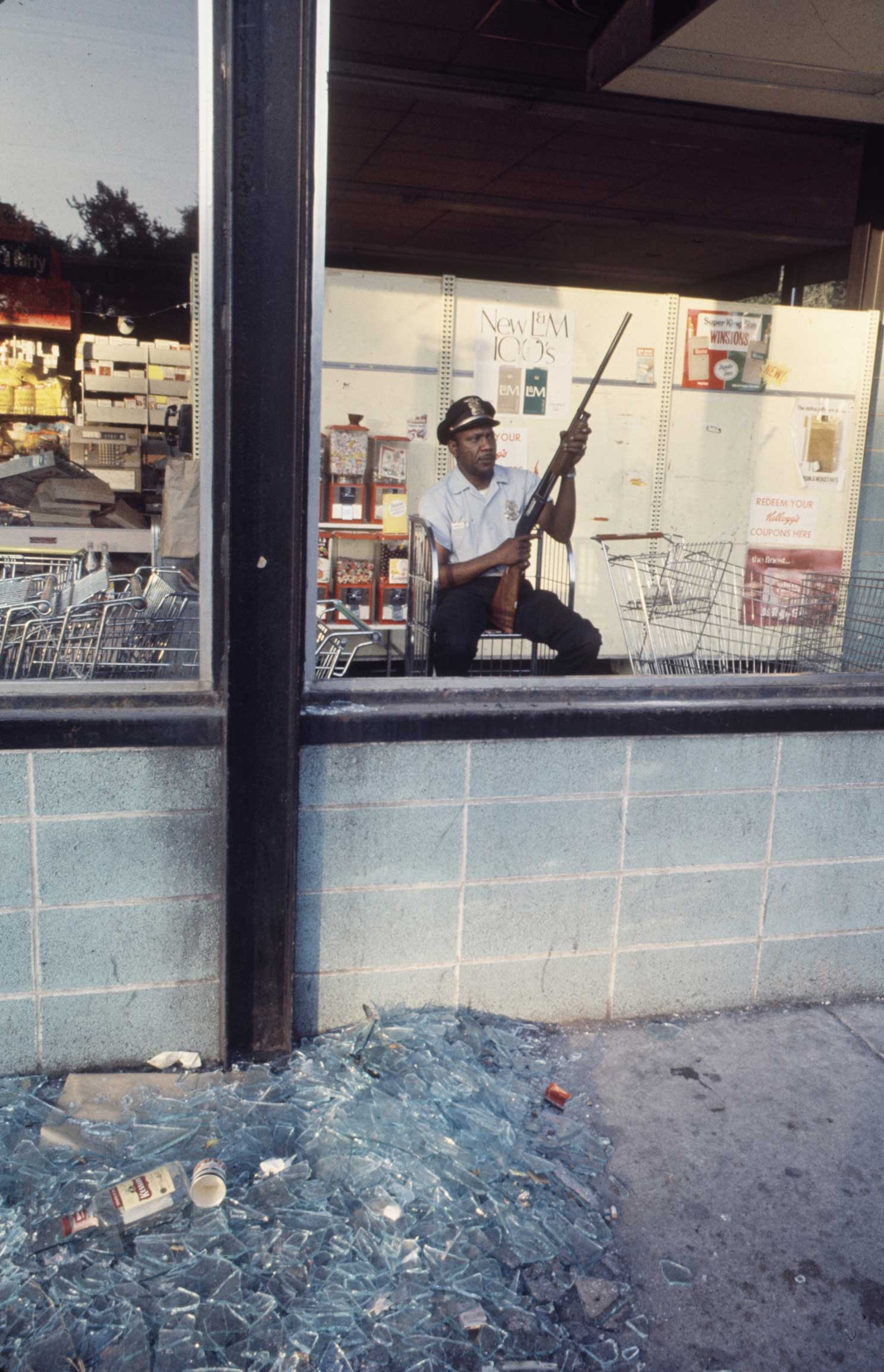

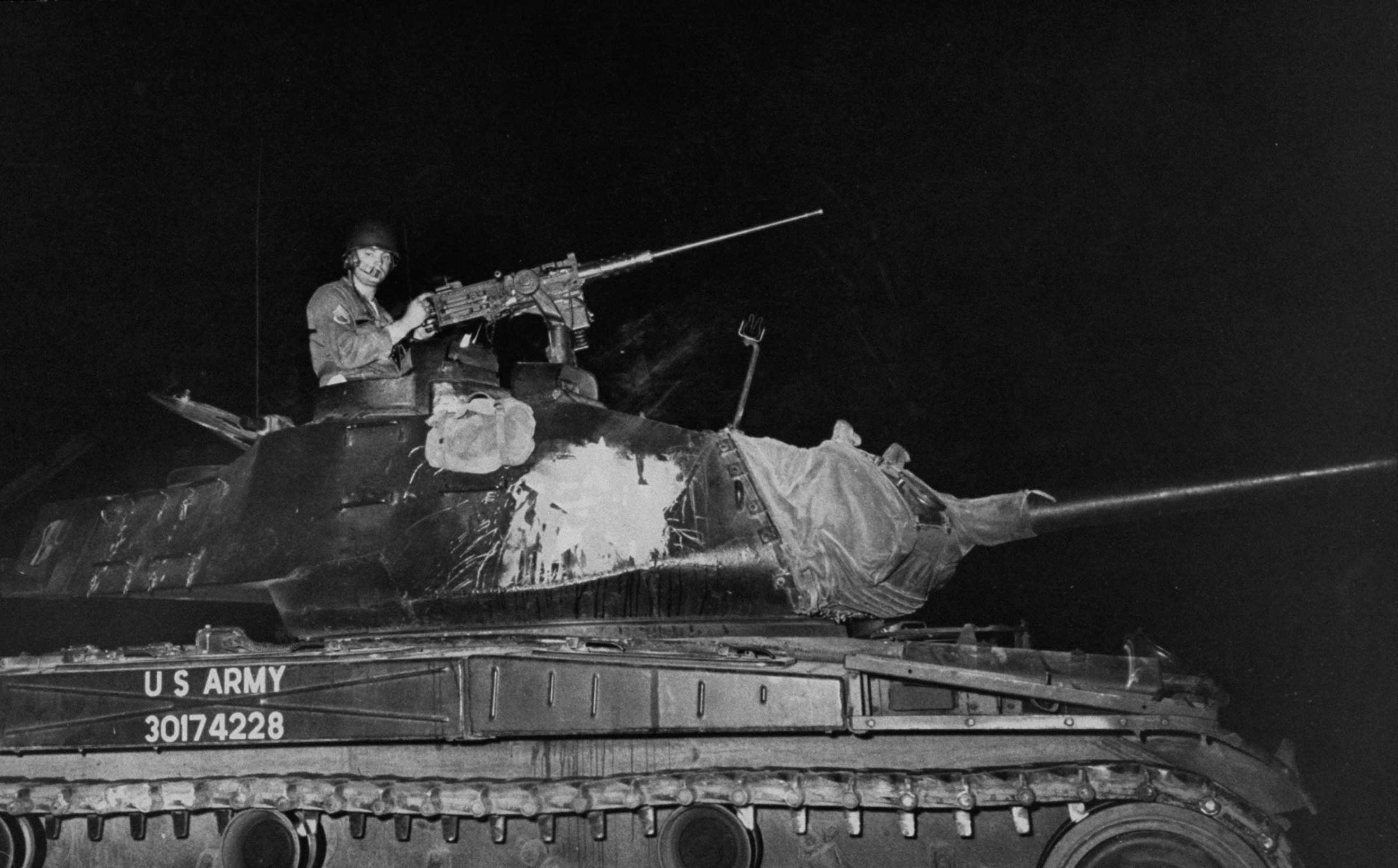

The days-long stretch of violence that July would leave 43 dead, hundreds injured, thousands arrested and even more homeless due to fire and destruction, in what TIME called “the bloodiest uprising in half a century and the costliest in terms of property damage in U.S. history.” As the magazine’s cover story on the events explained, it had started with a “routine” police raid on a “blind pig” (an afterhours club where alcohol could be purchased illegally) on the city’s West Side. But, beneath that moment lay deep wells of resentment between the city’s black population and its majority-white local government and law enforcement. When dozens of customers were arrested in the early hours of that morning, a crowd began to gather. As police attempted to get them into cars and away from the scene, a bottle was thrown.

The ensuing melee — which is most commonly called a riot though some argue would be better described as a rebellion — would not cease for five days, after the arrival of thousands of police officers, National Guardsmen and federal forces. Those days were also the time of the infamous incident at the Algiers Motel, which director Kathryn Bigelow explores in the new movie Detroit. (Locke was personally involved in that incident too, as he interviewed the two young women who were there after an attorney friend brought their story to his attention, saying that “he had two young women in his office who had a story to tell, and if 25% of it was true we had a real problem in the police department.”)

Many outside observers were surprised that things got so bad so quickly in Detroit. As TIME noted, though there had been a race riot in Detroit in 1943, the city was often held up as a shining example of peace in the mid-’60s. The city’s black middle class was relatively large and the local government stood out for its investments in programs to further alleviate poverty. The experts who tried to predict where the fuse would next blow left Detroit off their lists, especially after 1966’s so-called Kercheval incident, in which a potential riot had been successfully defused by a lucky rainfall and the work of local leaders and police. “Word went around the country that Detroit has been able to show the country how to handle a potential riot,” Locke says. “Well, that of course turned out to be a moment of great folly.”

So what had gone wrong? The magazine’s answer back then was that the riot was “the most sensational expression of an ugly mood of nihilism and anarchy that has ever gripped a small but significant segment of America’s Negro minority.”

But, looking back, the pervasive idea that Detroit was an expression of nihilism or despair misses a few key facts.

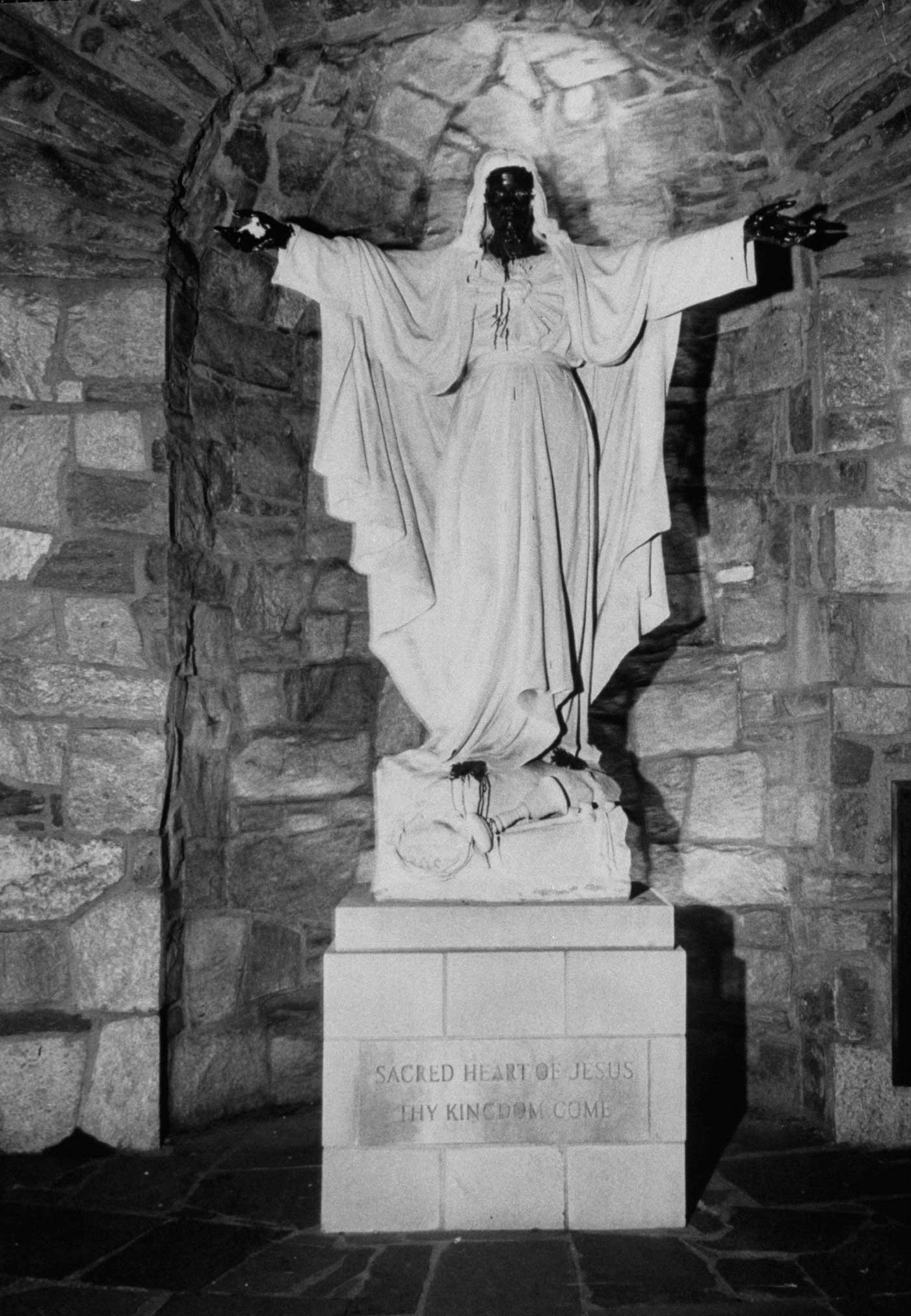

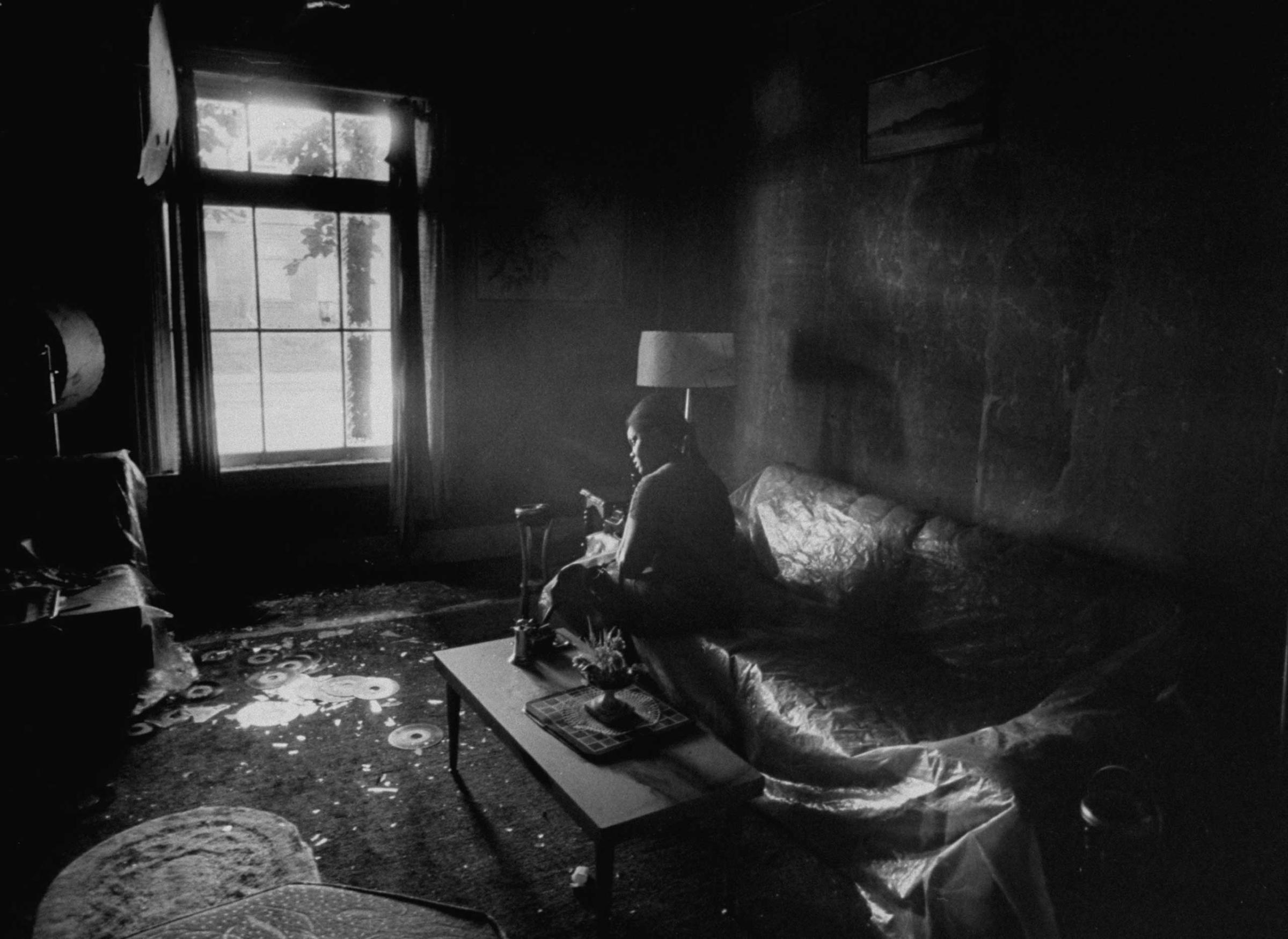

Detroit Burning: Photos From the 12th Street Riot, 1967

One of those facts is something that’s easier to see now than it was in 1967: The economic situation in Detroit was already set on a course toward the decline for which it is more recently famous. Locke says that it took him years to come to that conclusion. For a long time, he had thought that the subsequent decline of the once-vibrant city was a “direct result” of the riot, but he now believes that, if anything, it was the other way around.

“What I think we didn’t sufficiently recognize in 1967 is that we were right in the midst of the deindustrialization of Detroit, of the collapse of Detroit as the symbol of industrial America,” he says. The beginnings of automation meant that major employers like Ford could turn out the same number of cars with fewer employees, and the factories began to restructure and move. “In retrospect it’s so easy [to see]. At the time, Detroit had always been the home of the industrial process, the manufacturing process at its best, so we just weren’t prepared to face the reality of what was going on.”

Those changing economics were, he says, a key ingredient what happened in 1967 — and that’s an opinion echoed by historian Thomas Sugrue, author of The Origins of the Urban Crisis and of a new introduction to an anniversary reissue of John Hersey’s The Algiers Motel Incident.

Sugrue — who also questions the common wisdom that Detroit was the clear “worst” of the 1967 riots, as it was a proportionately larger city than Newark, for example, and flat numbers don’t reflect that difference — points out that Detroit and Newark both had deep histories of segregation, with large African-American populations in cities run by white-dominated governments. Both cities were already experiencing high degrees of disinvestment and depopulation, he says, well before the summer of 1967. And, as the process began, African-Americans tended to experience the worst of its consequences. “That’s another bit of conventional wisdom that’s completely wrong, that Detroit was thriving and then ’67 happened and all the whites left and all the businesses left. Detroit had been hemorrhaging jobs and population for at least 15 years,” he says.

As Sugrue notes, studies by sociologists and political scientists in the wake of the riots revealed that in fact the poorest residents of those cities were not the ones on the street. Rather, those who took to the streets tended to be “a notch up” — insecure economically but educated, politically aware and in a position to feel economic and social setbacks. The Zeno’s-paradox feeling, that progress was slowing or stopping, was a crucial ingredient in putting the city on the edge.

The mistake of seeing frustration but reading despair had serious consequences. The wave of calls for law-and-order politics that followed the summer of 1967 was predicated on the notion that the people who took the streets had done so because of amorality or nihilistic lawlessness.

“This may sound perverse, but the uprisings didn’t grow out of total despair and hopelessness, which is how they’re often perceived,” he says. “They grew out of a sense that we needed more disruption to accomplish real change.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com