Armed Venezuelan police stormed Thamara Candelo’s apartment complex at dawn on June 30, 2016. It was two weeks after her wedding day, and Candelo’s American husband, Joshua Holt, was lying in their bed in Caracas. One officer demanded to see his visa. Others ransacked the rooms, took Holt’s phone and finally ordered him to get into a pickup truck. For the next five hours, his gun-toting captors mocked and hit him. Then they took him to the Helicoide, a prison home to the Venezuelan intelligence police. He has not been allowed out since.

Holt, 25, sent this account of his capture in a letter last August to his parents, who live south of Salt Lake City in his childhood home. It was only the beginning of an ordeal his family could never have fathomed when the young couple met online through their church that year. Holt was accused of arms possession, though witnesses told his family and lawyers that they watched agents plant firearms in the apartment after the arrest. He and Candelo have been held without trial. Five preliminary hearings have been canceled, with no explanation other than judges or courts were unavailable.

According to his family, Holt has lost more than 50 lb. subsisting on the prison’s diet of uncooked chicken and raw pasta, meals former Helicoide inmates have claimed are mixed with feces. He was denied medical care for bronchitis, a kidney stone and pneumonia. When an infection spread from his jaw to his eye, authorities pulled a tooth and filled the hole with cement, right atop his exposed nerve. Holt became suicidal. On July 3, the 368th day of his imprisonment, he fell from his bunk when guards woke him, sustaining what his family fears was a concussion and a back fracture. “Demons stroll the hallways,” Holt wrote of the prison. “I have been told by 10 or 20 people, prisoners and guards, that I am here because I am American.”

At any given moment, a handful of innocent Americans are detained in grisly conditions by hostile governments. Others are held by terrorist groups. At least four U.S. citizens are currently imprisoned in Iran. A North Carolina pastor is jailed in Turkey, accused without public evidence of membership in a group the government considers to be terrorists. Last year, North Korea seized Otto Warmbier, an Ohio college student visiting Pyongyang on a tour program, and sentenced him to 15 years of hard labor for allegedly trying to steal a propaganda poster. Warmbier fell into a coma in captivity after “tortuous mistreatment,” according to his family, and died days after he was finally released in June. Three other Americans remain in prison in North Korea.

Many of the families of these captives are united by a faith that President Trump will do what it takes to win their loved ones’ release. As a candidate, Trump promised that his dealmaking skills would free innocent Americans held abroad. “This doesn’t happen if I’m president!” Trump tweeted a few weeks before Election Day, when Iran sentenced two Americans for allegedly spying. As President, Trump has indeed pushed forcefully, and personally. In April, his Administration negotiated the release of aid worker Aya Hijazi, who had been held for three years in an Egyptian prison. Trump sent a plane to pick her up and tweeted a photo montage of him and Hijazi with Lee Greenwood’s “God Bless the USA” playing in the background. He has boasted about the deal in interviews, saying it took him just 10 minutes in the Oval Office with Egyptian President Abdul Fattah al-Sisi to secure Hijazi’s release. “President Obama tried and failed many times over three years, but we were able to get this done in a very short period and that is an amazing victory for Aya and her family,” Trump tells TIME, adding that “there have been other releases, some that we can’t talk about.”

Senior White House officials have held dozens of meetings with captives’ families in the first months of the Administration. Deputy National Security Adviser Dina Powell speaks every two weeks with Babak Namazi, whose father and brother are imprisoned in Tehran and were the subject of Trump’s pre-election tweet. Lawyers for Andrew Brunson, the pastor detained in Turkey since October, say Trump aides have been involved in their case since the presidential transition.

MORE: Read an Interview With President Trump on U.S. Captives Abroad

All this outreach from the highest levels of government is why Josh Holt’s family believes Trump will be his savior. “Right after Trump’s Inauguration, I thought, He’s going to get him home,” Josh’s mother Laurie Holt tells TIME from her living room, where Faith – family – friends is stenciled above the window. Laurie was invited to the White House in April. Even Donald Trump Jr. has weighed in on behalf of the Holts, according to Republican Senator Orrin Hatch of Utah. At one point, Trump Jr. offered to go to Venezuela, Hatch says. A lawyer for Trump Jr. did not return multiple requests for comment, and the Trump Organization declined to comment.

U.S. Presidents have often struggled with the challenge of when to trade favor or treasure for Americans captured abroad. Trump says he will deal forcefully with foreign adversaries. “We are aggressively pursuing the release of our people. We will leave no lawful tool, partnership or recovery option off the table,” Trump tells TIME. “I am always tough on countries or terrorist groups that hold our people hostage or detain them on fake charges and keep them captive in hellish locations far from their family and loved ones.”

Trump may find that the issues are not as black and white as he and the families that have placed their hope in him initially thought. In the past, hostile foreign governments have demanded a high price for the release of captives, from the release of criminals in the case of Iran to diplomatic concessions in the case of North Korea. “Securing the release of American hostages is really hard,” says longtime U.S. diplomat James Dobbins, now a senior fellow at the Rand Corp. “Normally, the only options are to rescue or ransom them. Rescue requires first locating them and is not even an option when they are being held by another state. Paying ransom is against U.S. policy as it only encourages more hostage taking. This leaves U.S. officials with a very narrow range of alternatives.”

When foreign adversaries take captives, the course of history can change. It’s a tribal tale woven through mythology. When Hades kidnapped Persephone, despair killed all the fruits of the earth until the Greek gods reached a compromise. The Trojan War of Homer’s Iliad was fought to bring home Menelaus’ wife Helen, the woman whose face launched a thousand ships. In America’s earliest days, President George Washington paid ransoms for shipping crews taken by Algerian pirates. Less than a decade later, Thomas Jefferson refused to do the same, starting the First Barbary War. Jimmy Carter’s presidency buckled under the humiliation of Iranian revolutionaries holding 52 Americans for 444 days. When George W. Bush was in the White House, Colombia’s Revolutionary Armed Forces held three American defense contractors captive for five years until they were rescued in a military helicopter operation.

Barack Obama’s presidency changed in the summer of 2014, when the Islamic State beheaded an American hostage, freelance journalist James Foley, and posted the macabre footage online. Two other Americans met a similar end. In the aftermath, several of their families spoke out against what they saw as the Obama Administration’s inaction and refusal to pay the ransoms the terrorists demanded. (By contrast, many European governments do pay ransoms.)

Partly in response, Obama created the first-ever special presidential envoy for hostage affairs as well as a new interagency Hostage Recovery Fusion Cell to coordinate intelligence, diplomatic, legal and military efforts to bring Americans home safely and to better communicate with victims’ families. By most accounts, the new efforts were an improvement. Many families finally felt like the Administration was giving them the voice and information they desired amid the bigger geopolitical policy priorities. “Our citizens are held as hostages because they are Americans, so getting them released means understanding what kidnappers want from America,” says James O’Brien, Obama’s hostage envoy.

Despite the political rancor over Trump’s election, aides to both Administrations have largely cooperated on hostage and detainee cases. “Obama deserves some credit,” Homeland Security Adviser Thomas Bossert said at an Aspen Institute event in mid-July. But the new Administration has also gone its own way.

Trump’s first hostage crisis came early in his presidency. Two months after Trump negotiated Hijazi’s release from Egypt, he got on the phone with Warmbier’s parents, who were in disbelief about their son’s incurable comatose state. “It was, ‘Are you taking care of yourself?’ and, ‘We worked hard, and I’m sorry this is the outcome,'” Otto’s father Fred recalled, days before his son died. Trump sent Powell to the funeral in Ohio to represent the White House. “Otto’s fate,” Trump said, “deepens my Administration’s determination to prevent such tragedies from befalling innocent people.”

Trump directed the National Security Council to create strategies for each detainee, a senior Administration official says. Take the case of the Namazi family. Siamak Namazi, a 45-year-old businessman and dual citizen of the U.S. and Iran, was visiting his family in Tehran in 2015 when authorities intercepted him at the airport and locked him in solitary confinement. For months, his father Baquer, 80, who is also a dual citizen, went to the prison every day to beg the guards to let him see his son. Then he, too, was seized. In a petition filed to the U.N., their lawyer Jared Genser notes that Iranian authorities have presented no evidence to support their accusation that the Namazis were spying. Since Trump’s Inauguration, Babak Namazi, Siamak’s brother and Baquer’s son, has been invited to the White House four times, an opportunity never granted under Obama. Trump Administration officials raised the Namazi case with Iranian counterparts in Vienna this spring during a compliance review of the 2015 Iran nuclear deal. On July 21, the Trump Administration threatened Iran with “new and serious consequences” unless all unjustly imprisoned Americans were returned.

Lawyers for Brunson, the North Carolina pastor detained in Turkey, also praise Trump’s support. Brunson, who had lived in Turkey for 23 years, was accused of being tied to a cleric, now in the U.S., whom the Turkish government accused of staging a coup against President Recep Tayyip Erdogan last year.

Brunson’s attorney Jordan Sekulow, the son of Trump’s personal lawyer Jay Sekulow, says it took a petition with hundreds of thousands of signatures to get the Obama White House to focus on the fate of a former client, pastor Saeed Abedini, who was held in Iran before being freed after the implementation of the nuclear deal with Iran. In contrast, Sekulow began working with Vice President Mike Pence’s staff on the Brunson case shortly after Election Day. Secretary of State Rex Tillerson met with Brunson’s wife Norine when he visited Turkey in March. When Trump hosted Erdogan in the Oval Office in May, he asked for Brunson’s release and insisted that the request be included in the meeting’s readout.

“They are different than the Obama Administration, which was strategy before action, heavier on strategy, lighter on action,” says David Bradley, chairman of Atlantic Media, who has worked closely with the families of Americans captured by the Islamic State. “The Trump Administration is more focused on action, pedal to the metal, one to take much greater risk, politically.”

Trump’s moves have drawn plaudits from supporters across the U.S. as well as Republicans on Capitol Hill. Evangelist Franklin Graham asked his nearly 6 million Facebook followers to thank Trump for pushing for Brunson’s release. Republican Congresswoman Ileana Ros-Lehtinen of Florida is among those to praise Trump for issuing three rounds of sanctions against Venezuelan officials. “It’s absolutely true,” says Senator Marco Rubio of Florida, “that this White House has placed a higher priority on securing the release of Americans unfairly jailed or detained overseas than the previous Administration did.”

Trump’s approach raises questions of its own. Obama never invited al-Sisi to the White House: his rise to power included a coup, and the State Department and outside observers have criticized the regime’s repeated human-rights abuses. Even though Trump’s Oval Office sit-down with al-Sisi resulted in Hijazi’s release, critics feared the invitation signaled the Administration’s blessing of the regime. Broader policy discussions, Obama’s envoy O’Brien says, are necessarily part of getting hostages released. Iran and Cuba released U.S. prisoners after extensive diplomatic and security negotiations with Obama Administration officials. “Seeking the release of a hostage without encouraging more such incidents requires more patience, subtlety and dedication to the task than most American leaders can bring to bear, or risk,” says Christopher Hill, a four-time ambassador under three Presidents.

Families too are beginning to worry that geopolitical realities may make it hard for Trump to deliver on his promises. On July 26, the Trump Administration announced the latest round of sanctions on current and former Venezuelan officials. “I am concerned that the government does not take into consideration the possible negative consequences that these sanctions could have on Josh Holt,” says Holt family lawyer Carlos Trujillo.

There’s also a concern that Trump’s impulsive comments could complicate other strategic U.S. efforts to get captives released. The same day that Chinese Nobel laureate and human-rights activist Liu Xiaobo died after nearly a decade as a political prisoner, Trump called Chinese President Xi Jinping “a terrific guy” for whom he has “great respect.” The White House later stated that Trump was “deeply saddened” by Liu’s death, but some activists feared that Trump had effectively removed any incentive for Xi’s government to free Liu’s wife, who remains under house arrest, and potentially undercut his Secretary of State’s call for the government to set her free, made the same day.

Then there are practical matters. Trump has not appointed a new special presidential envoy for hostage affairs, the position Obama created to streamline solving such cases and to centralize assistance for hostages’ families. The Hostage Recovery Fusion Cell continues its work, but largely devotes its resources not to cases of Americans like Warmbier or Holt, who were detained by governments, but to criminal and terrorist hostage cases, where Americans have been kidnapped by nonstate actors. Financial assistance for victims is similarly split, leaving those detained by foreign governments in the lurch. “As a country, we should be helping the few people unfortunate enough to become political causes,” O’Brien says. “It is important that the U.S. government do more to support the families and the prisoners once they come home.”

None of this has dimmed the Holt family’s faith in Trump. Soon after Josh’s parents got word last summer that he and Thamara had been taken, they reached out to their elected officials and learned to use WhatsApp to communicate with their South American legal team. Within a week, they launched a #JusticeForJosh social-media campaign and asked people to tweet at then candidate Trump. “We have gotten word he could help us,” the family posted on Facebook in July 2016.

At first, Laurie says, she had a hard time getting Washington’s attention, though Secretary of State John Kerry brought up Josh’s case when he spoke with Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro in September 2016. When Laurie first visited D.C. last fall, she had meetings with State Department officials and her local representatives. Soon after, she says, U.S. officials recommended that the family keep Josh’s case quiet during a pending U.S. Administration change. But as the months went on, she and her husband became convinced that that was a mistake.

When she returned to Washington in April, Laurie was surprised and relieved to be invited to the White House. For an hour, the 49-year-old accountant sat down with Trump’s then Deputy National Security Adviser, K.T. McFarland, who assured her that the President was already aware of her son’s case. Laurie has not heard from the White House since then, and McFarland has left the White House.

Behind the scenes, Trump Jr. has been working with Hatch to get Holt released, the Senator says. During the 2016 presidential race, Trump Jr. and Hatch had campaigned together in heavily Mormon districts out west, and Hatch brought up Holt’s case. Since his father took office, Trump Jr. has remained involved, Hatch says. At one point, Hatch says Trump Jr. brought in friends from New York who did business in the region. “They indicated they might be able to do something,” Hatch says. “I was willing to stretch real hard to help them if they would help get this young man out.” But the idea was ultimately discarded, according to Hatch.

On a Friday evening in early July, the Holt family held a press conference near their Utah home. In a landscaped park featuring splash playgrounds and basketball courts, Holt’s parents pleaded with Trump and U.N. ambassador Nikki Haley to intervene on Josh’s behalf. Hatch spoke, and friends came from their Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints congregation and from Holt’s high school football team. But the rally was small compared with the scene on the other side of the park, where kids cartwheeled and families picnicked, enjoying the end of a summer workweek.

It was a reminder of just how lonely their struggle remains. When Laurie and Jason leave for work each morning, they see an American flag across the street atop their church flagpole, which Josh built for his Eagle Scout project. When they return home, they spend their evenings calling their lawyers, researching new strategies and trying to be good parents to their three other children, who have at times felt placed on the back burner. They shelled out more that $30,000 for their first legal team before they found new representation. Even in captivity, Josh’s car payments and other bills are still due.

Venezuela’s political crisis has accelerated as its economic situation deteriorates. Maduro plans to hold a vote on July 30 that senior Administration officials say will move his rule toward dictatorship. In 2016, three-quarters of Venezuelans lost an average of 19 lb. each amid food shortages, according to a survey on living conditions there. Violent police raids on apartment complexes have continued, and in May, Venezuela launched Operation Knock-Knock to round up alleged antigovernment conspirators. Washington and Caracas have not had ambassadors since 2010, and in December the State Department issued a warning to U.S. citizens against visiting Venezuela.

Venezuela’s national oil company gave $500,000 to Trump’s Inauguration through Citgo Petroleum, the subsidiary it owns in the U.S. and which the Holts are boycotting. But after Trump’s second round of sanctions against its officials in May, Maduro soured on the Trump Administration. “Get your dirty hands out of here,” he said in a televised speech to Trump, who has called the Venezuelan humanitarian crisis “a disgrace to humanity.” Meanwhile, Russian President Vladimir Putin started sending several thousand tons of wheat each month to Venezuela, which leveraged nearly half of Citgo for a loan from a Russian state-owned oil company. (The Venezuelan embassy in D.C. did not comment on Holt’s case, after multiple requests.)

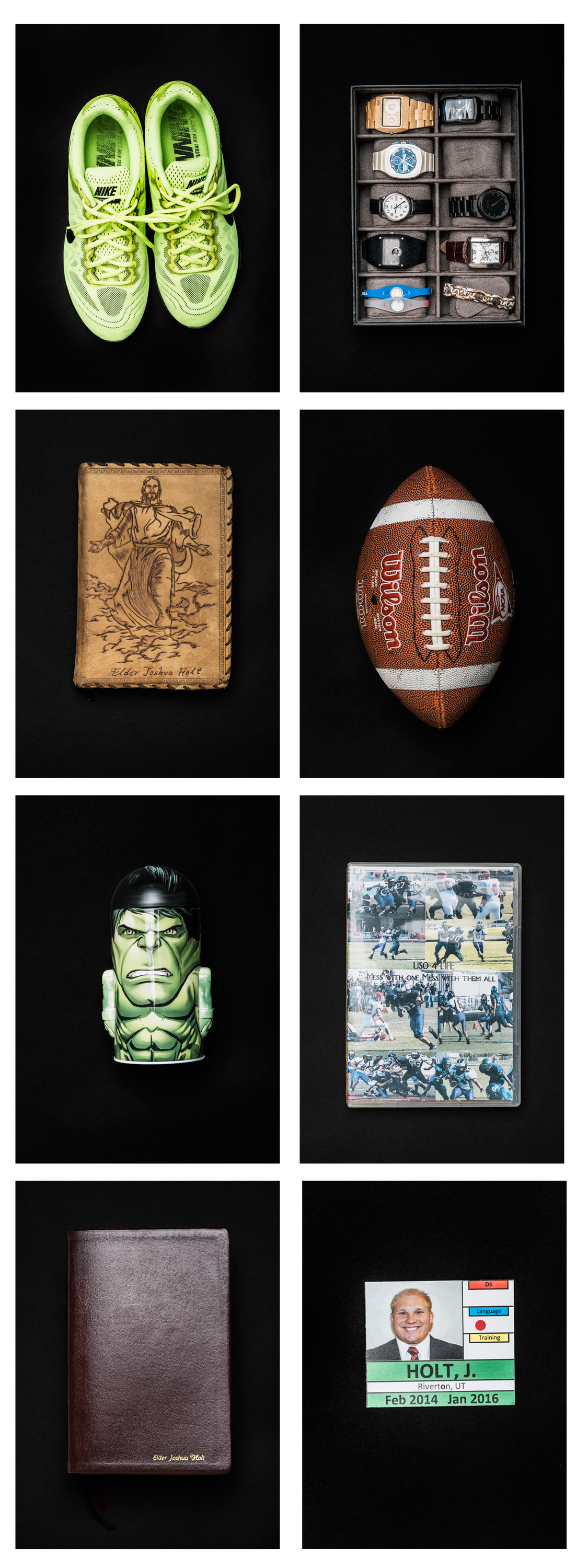

The Holts refuse to give up. Every so often, Laurie goes downstairs to dust her son’s bedroom. It remains almost exactly as it was the day he left. A painting of Jesus hangs above the foot of his bed, where he wanted it to be so that he could see it first thing each morning. Josh’s wristwatch collection sits in a box on his dresser, save the favorites he took to Venezuela for his wedding, lost now to prison guards. Laurie has filled his closet with gifts for her son’s new family, ready for whenever Josh and Thamara are freed. There are winter snow bibs from when she hoped they’d be home for Christmas, and now, in summer, Hello Kitty dresses for her new granddaughters. The tags are still on.

“All our family wants is to have him and his family home with us, so that we can start to be whole again,” Laurie says. “His only mistake was falling in love with somebody that was so far away.”

–With reporting by MASSIMO CALABRESI/WASHINGTON

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com