As the fight over reforms to the American health-care system continues this week, Tuesday marks the 45th anniversary of a grim milestone in the history of health care in the U.S.

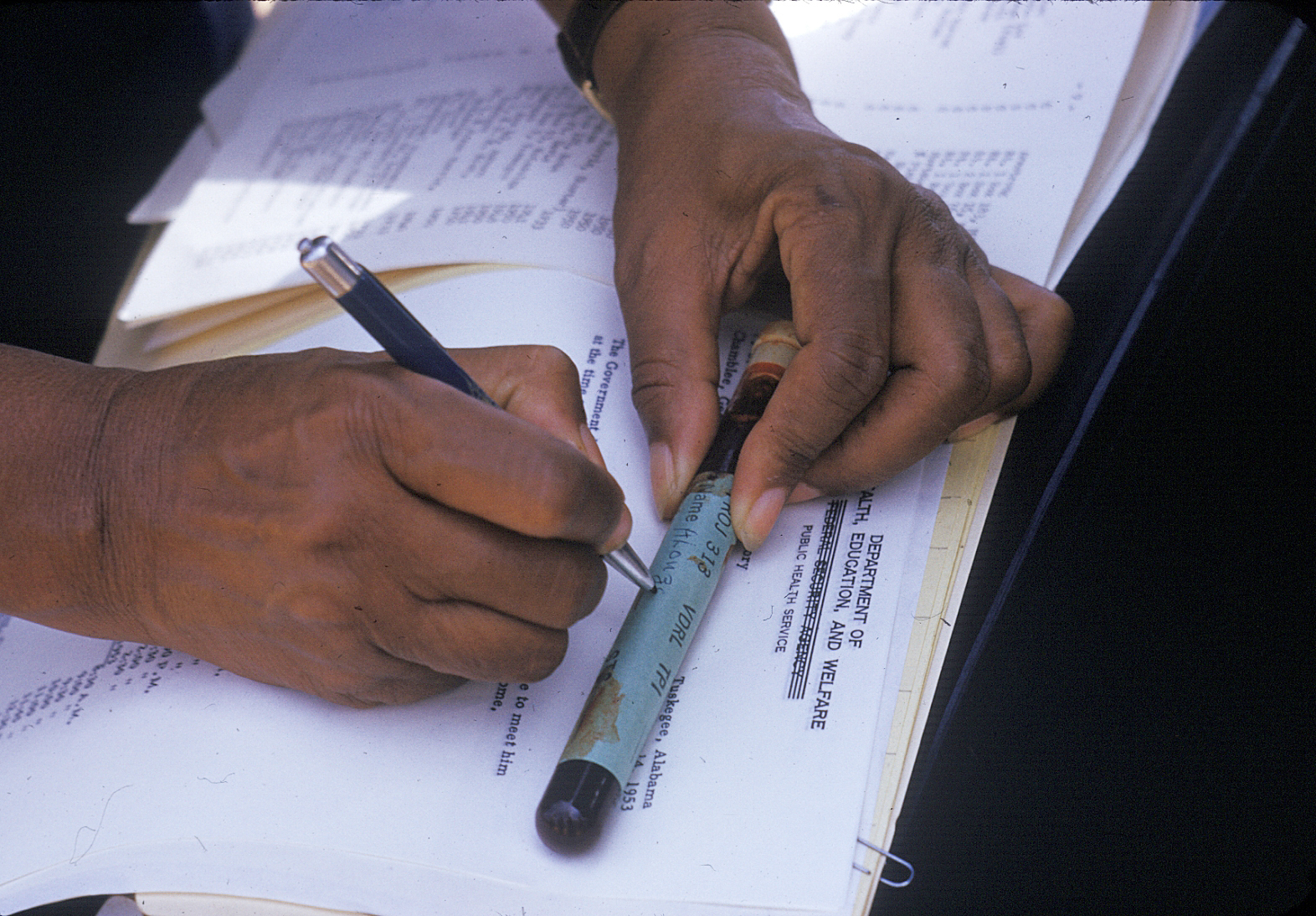

On July 25, 1972, the public learned that, over the course of the previous 40 years, a government medical experiment conducted in the Tuskegee, Ala., area had allowed hundreds of African-American men with syphilis to go untreated so that scientists could study the effects of the disease.

“Of about 600 Alabama black men who originally took part in the study, 200 or so were allowed to suffer the disease and its side effects without treatment, even after penicillin was discovered as a cure for syphilis,” the Associated Press reported, breaking the story. “[U.S. Public Health Service officials] contend that survivors of the experiment are now too old to treat for syphilis, but add that PHS doctors are giving the men thorough physical examinations every two years and are treating them for whatever other ailments and diseases they have developed.”

By the time the bombshell report came out, seven men involved had died of syphilis and more than 150 of heart failure that may or may not have been linked to syphilis. Seventy-four participants were still alive, but the government health officials who started the study had already retired. And, because of the study’s length and the way treatment options had evolved in the intervening years, it was hard to pin the blame on an individual — though easy to see that it was wrong, as TIME explained in the Aug. 7, 1972, issue:

At the time the test began, treatment for syphilis was uncertain at best, and involved a lifelong series of risky injections of such toxic substances as bismuth, arsenic and mercury. But in the years following World War II, the PHS’s test became a matter of medical morality. Penicillin had been found to be almost totally effective against syphilis, and by war’s end it had become generally available. But the PHS did not use the drug on those participating in the study unless the patients asked for it.

Such a failure seems almost beyond belief, or human compassion. Recent reviews of 125 cases by the PHS’S Center for Disease Control in Atlanta found that half had syphilitic heart valve damage. Twenty-eight had died of cardiovascular or central nervous system problems that were complications of syphilis.

The study’s findings on the effects of untreated syphilis have been reported periodically in medical journals for years. Last week’s shock came when an alert A.P. correspondent noticed and reported that the lack of treatment was intentional.

About three months later, the study was terminated, and the families of victims reached a $10 million settlement in 1974 (the terms of which are still being negotiated today by descendants). The last study participant passed away in 2004.

Tuskegee was chosen because it had the highest syphilis rate in the country at the time the study was started. As TIME made clear with a 1940 profile of government efforts to improve the health of African Americans, concern about that statistic had drawn the attention of the federal government and the national media. Surgeon General Thomas Parran boasted that in Macon County, Ala., where Tuskegee is located, the syphilis rate among the African-American population had been nearly 40% in 1929 but had shrunk to 10% by 1939. Serious efforts were being devoted to the cause, the story explained, though the magazine clearly missed the full story of what was going on:

In three years, experts predict, the disease will be wiped out. To root syphilis out of Macon County, the U. S. Public Health Service, the Rosenwald Fund and Booker T. Washington’s Tuskegee Institute all joined forces. Leader of the campaign is a white man, the county health officer, a former Georgia farm boy who drove a flivver through fields of mud, 36 miles a day to medical school. Last month, deep-eyed, sunburned Dr. Murray Smith began his tenth year in Macon County. “There’s not much in this job,” said he, “but the love and thanks of the people.”

At first the Negroes used to gather in the gloomy courthouse in Tuskegee, while Dr. Smith in the judge’s chambers gave them tests and treatment. Later he set up weekly clinics in old churches or schoolhouses, deep in the parched cotton fields. Last fall the U. S. Public Health Service gave him a streamlined clinic truck. The truck, which has a laboratory with sink and sterilizer, a treatment nook with table and couch, is manned by two young Negro doctors and two nurses. Five days a week it rumbles over the red loam roads. At every crossroads it stops.

At the toot of its horn, through the fields come men on muleback, women carrying infants, eager to be first, proud to have a blood test. Some young boys even sneak in to get a second or third test, and many come around to the truck long after they have been cured. One woman who had had six miscarriages got her syphilis cured by Dr. Smith with neoarsphenamine. Proudly she named her first plump baby Neo.

In the years following the disclosure, the Tuskegee study became a byword for the long and complicated history of medical research of African Americans without their consent. In 1997, President Bill Clinton apologized to eight of the survivors. “You did nothing wrong, but you were grievously wronged,” he said. “I apologize and I am sorry that this apology has been so long in coming.” As Clinton noted, African-American participation in medical research and organ donation remained low decades after the 1972 news broke, a fact that has often been attributed to post-Tuskegee wariness.

In 2016, a National Bureau of Economic Research paper argued that after the disclosure of the 1972 study, “life expectancy at age 45 for black men fell by up to 1.5 years in response to the disclosure, accounting for approximately 35% of the 1980 life expectancy gap between black and white men and 25% of the gap between black men and women.” However, many experts argue that the discrepancy has more to do with racial bias in the medical profession.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- L.A. Fires Show Reality of 1.5°C of Warming

- Home Losses From L.A. Fires Hasten ‘An Uninsurable Future’

- The Women Refusing to Participate in Trump’s Economy

- Bad Bunny On Heartbreak and New Album

- How to Dress Warmly for Cold Weather

- We’re Lucky to Have Been Alive in the Age of David Lynch

- The Motivational Trick That Makes You Exercise Harder

- Column: No One Won The War in Gaza

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com