Twenty yards north of the U.S.-Mexico border the steel fence forms a tall, cage-like enclosure around the plaza of San Diego’s International Friendship Park. A pair of armed Border Control agents and a towering metal pole bristling with surveillance cameras keep tabs on visitors to the American side’s flat, featureless expanse of paved concrete. The Mexican side is filled with food trucks, picnic tables, planters full of flowers, and people enjoying a Sunday afternoon.

Friendship Park was dedicated by First Lady Pat Nixon in 1971 as a gesture of goodwill between nations. At first there was no fence; later, only a chain link. In 2009, citing concerns about the passing of drugs, weapons, and other contraband, the United States government built a secondary barrier before closing the park, at the time indefinitely. The area reopened in 2012, but with both visitation hours and the number of visitors under tighter control. A sign at the entrance now sets a 25-person limit on the number of people that can be inside the plaza, which is only open on Saturdays and Sundays between 10:00 AM and 2:00 PM.

For some documented immigrants like Alex Valenzuela, who has driven two-and-a-half hours from Los Angeles with his wife, Michele, and their nine-month-old daughter, Zamora, this is the only place to see family members living on the other side of the divide. Valenzuela can’t leave the U.S. while he’s waiting for his green card paperwork to clear. His mother, who has driven two hours north from Ensenada, Mexico, is still waiting for a visa to enter the country.

“This is only the second time she’s seen her granddaughter,” he says. “I told her that in two months, when I get permission to leave, I may surprise her on the other side. She started crying.”

The two can barely see one another through the steel thicket that divides the park, and dense steel mesh makes hugging through the fence impossible. Here, the standard greeting is to touch pinkie fingers through the tiny openings.

This scene represents a popular idea of the Mexican border in Trump’s America—the wall the President has repeatedly claimed he will build is, after all, the promise of a physical barrier, a blockade meant to keep people out. But the border is no mere line in the sand begging for imposing battlements; the nearly 2,000 miles of land is a vast and changing landscape inhabited by citizens of both nations and more, businesses both legal and illicit, guardians of the divide both official and vigilante—and, most often, filled with nothing but lonely earth. It is a porous division between countries, and communities, that rely on one another.

To better understand this complex region, we traveled a large swath of it, starting in San Antonio, Texas, and heading south to Laredo, then pushing west along the border toward the Pacific Ocean, talking to residents of both countries, government officials, volunteers, and refugees along the way.

Mexico

The La Linea cartel owns this place. The organization has eyes and ears everywhere in Anapra, one of the poorest neighborhoods in Juarez, Mexico, and if you’re not from the area the cartel knows you’re here as soon as your tires leave the highway that runs through it. The town sits on a plain between a mesa and a ridge, next to a border fence still under construction. The smell of sewage wafts over unpaved streets choked with plastic trash. The houses are ramshackle and the fencing around them made from old pallets, mattress springs, plywood. Our guide leans out the window of his car and asks a group of young boys in dirty shirts where we can find Victor Martinez.

Martinez, who lives in the neighborhood, is a coyote: he helps smuggle migrants across the border into Texas and New Mexico. Martinez is small and lithe, his face brown and sun-creased with a triplet of blue dots tattooed into the skin just below his left eye. He smiles easily, revealing a gold tooth.

Our guide reminds us that purposeful movement is essential in Anapra. It needs to be made clear to anyone watching that, say, a reporter’s notepad or his camera are not weapons. This is particularly true if you’re spotted by Pitbull, the cartel operative who runs the area, or one of his crew.

“Most of these guys are stoned all the time—you have to be very deliberate so they don’t get confused,” explains our guide, Luis Chaparro, a 30-year-old freelance journalist based in Juarez. “All the heroin that doesn’t make it across the border has to be sold, so they get good quality heroin very cheap.”

Chaparro tells us that the cartel has posted signs in the area warning methamphetamine addicts to switch to heroin or face dire consequences. The rival Sinaloa cartel, run by the infamous Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán, produces meth and moves it through Juarez, among other places, but La Linea’s bosses don’t like the competition working their turf. Collecting addiction statistics is notoriously dangerous for government surveyors, so accurate numbers are hard to pin down, but Chaparro puts heroin addiction in Juarez at three times the national average.

We follow Martinez and his 10-year-old son, Brian, through a dusty gulch running beside a section of the new, 18-foot-tall steel border fence. A pair of boys from the neighborhood appears, wearing grubby clothes and asking for dollars, eager to show us how easy it is to get around the fence. The men building the fence on the U.S. side ignore us. We walk to the end of the fence, then around it, taking a few steps into the U.S. A Border Patrol truck with wire mesh cages bolted to its windows sits nearby. If there’s an agent inside, he also ignores us. In the distance, on the peak that stands between Anapra and El Paso, we see a man with a backpack climbing slowly toward the top. A few minutes later, he disappears from view.

“He’s going to the States,” Chaparro observes.

Every few minutes, a freight train lumbers slowly by. Standing beside the fence, Martinez explains that at night, migrants can hop onto the train, crawl between the cars, and jump out the other side before Border Patrol officers can figure out where they are. He and other coyotes use ladders to climb to the top of the fence and scan the valley for Border Patrol trucks. He tells us that sometimes the cartel, which rakes in money from illegal immigration, shoots at Border Patrol trucks, whose drivers almost always elect to relocate to a safer location. The coyotes are familiar with the Border Patrol’s rules of engagement and uses them to their advantage.

Martinez says that it has taken the U.S. nearly a decade to build the fence through this valley because people from the neighborhood repeatedly pilfered construction materials at night. A chain-link fence that predates the new steel barrier lies on the ground, on the Mexican side of its replacement. Martinez says it has already been scoped out by scrappers, who will dismantle it and sell the metal somewhere else in Mexico.

“This wall is pointless,” Martinez says, adding that he and his colleagues already have plans to cut holes in the new wall. “We’ll get around it.”

Chaparro nods in agreement, and adds the cartel is sending most of its drugs through the ports of entry, anyway.

According to U.S. Customs and Border Protection data, Border Patrol—known as La Migra among Spanish-speakers—apprehended nearly 200,000 illegal immigrants between October of 2016 and March 2017. That number included 59,000 family units traveling together, and more than 28,000 unaccompanied children—an 82-percent increase in family units and a three-percent rise in unaccompanied children over the same period the year before.

Those numbers reflect migration across the entire border, but Border Patrol’s El Paso sector, which covers the southern edge of New Mexico and a small part of West Texas, has seen family unit migration apprehensions jump 268 percent since last year, and unaccompanied child apprehensions in the sector rose by 61 percent. That is because many of the detainees are fleeing violence-ravaged nations in the so-called Northern Triangle: El Salvador, Honduras and Guatemala.

The demographics of immigration across the border with Mexico have shifted over the past 15 years. Whereas Mexican immigrants and single adults once dominated the statistics, Central American families and unaccompanied minors have recently become more prominent. In 2016, Border Patrol agents apprehended nearly 70,000 unaccompanied children and more than 77,000 families, many asylum seekers from the Northern Triangle.

Martinez and his son are focused on getting migrants—and sometimes, drugs—across the border through Anapra. Martinez says he gets $150-$200 per person and guides around 10-15 people per trip—a small piece of the total amount cartels usually charge. Depending upon point of origin, that fee usually stretches into the thousands. Migrants pay in advance, almost always by wire transfer.

“We’re more civilized now,” Martinez says with a grin.

Brian knows all the routes, too, and demonstrates how his small size gives him an edge when he needs to wriggle through fencing. Getting caught by La Migrais no big deal, he says; they just deport him back to Juarez. Asked if his son will follow in his footsteps when he grows up, Martinez shrugs and asks, “Why not?” in Spanish. It’s a family affair, after all: Brian’s father and uncle are both coyotes.

Despite their willingness to work for the cartel, the Martinez family knows that danger is ever-present in such an occupation. They tell me a 16-year-old boy from the neighborhood was recently kidnapped because he lost some of the cartel’s money. Brian says matter-of-factly that he heard from a neighbor that the boy is scheduled to be executed tonight.

As we chat outside Martinez’s front gate, he glances up the street.

“Pitbull sees us,” he says. “Time to go.”

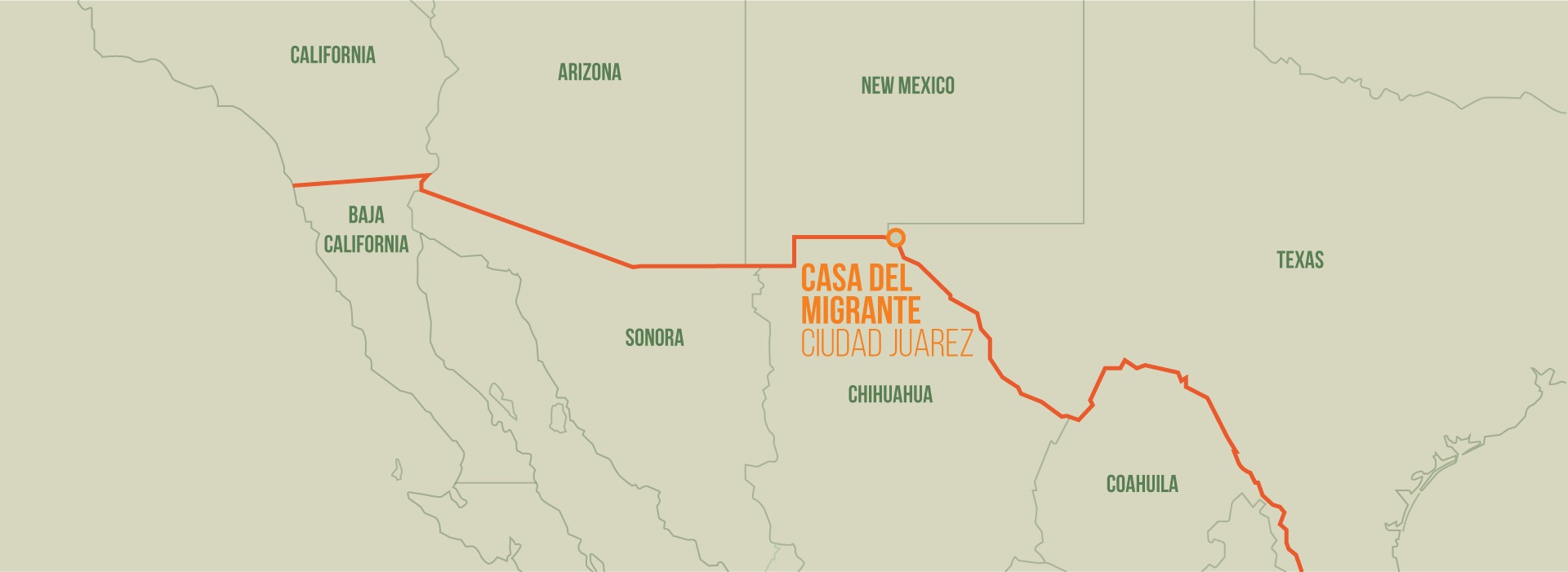

Anna Lizette Bonilla, 28, left her home in Honduras with her husband and one-year-old son on May 11 of last year. She says her husband owned a cell phone repair shop and was being extorted by a cartel. When the cartel threatened the Bonilla family, they decided to leave the country.

Bonilla says that after traveling across Guatemala the family learned that if they arrived at the Mexican border checkpoint after 7 p.m., it would be deserted. So they crossed the border into Chiapas state, Mexico, at night. They stayed put for six months as they waited to see if Mexico would grant them asylum.

Bonilla’s husband sold fruit while the family waited for Mexican authorities to reach a decision. The couple was trying to save money, but their son, Luis, had chronic stomach problems and the medical bills took a toll. Eventually, Mexico gave the Bonillas refugee papers, and they were able to take a public bus to the U.S. border at Juarez. Because they had no money—they scraped together travel funds by begging and picking up odd jobs along the way—it took another four months to reach their destination.

Not long after arriving in Juarez, a new Bonilla was born. And by the time the Bonilla family was ready to enter the U.S. and request asylum, Donald Trump had been sworn in as president.

“The president of the United States is threatening families,” Bonilla says in Spanish, holding her older son on her lap at the Juarez shelter they now call home. “We could be separated from our children—they would stay in the U.S. while we have to return to Mexico or Honduras.”

She says they never intended to stay in Mexico, but that the new administration changed everything. Juarez isn’t the U.S., but it’s okay. They don’t feel like their security is threatened, and her husband got a job in a cardboard factory. They’re living in the shelter, but eventually, she says, they will have to get their own place.

“If Donald Trump was a different person, we would try to go to the U.S.,” Bonilla says.

Like many Mexican border cities, Tijuana is a collection point for people attempting to travel north in search of job opportunities. But if they can’t get across, many have nowhere else to go. The lucky ones end up in shelters, but my guide for the day, a Border Angels volunteer named Hugo Castro, tells me that there are homeless encampments scattered all over the city as a result of the overflow. One of the largest shantytowns once occupied the concrete channel in the Tijuana River, but the police burned it down.

Some of Tijuana’s poorer neighborhoods are themselves only a step above shantytowns—houses without electricity or sewage hookups perched on steep, crumbling hillsides. Scorpio Canyon, one of the shelters Border Angels works with, is in such an area.

“When it rains, you can’t even drive back here—you have to get out and walk,” Castro explains as his Nissan sedan bumps and scrapes over dirt and rocks. “There have been people living back here for 40 years, but the government doesn’t give them services.”

He drives the car up an incredibly steep dirt driveway and parks in front of what looks like the biggest and most solid structure in the canyon. This is Reverend Gustavo Banda Aceves’s Iglesia Embajadores de Jesús. Right now, the aircraft hangar-sized church is home to several dozen vagabond Haitians who have been wandering the Americas in search of a permanent home since a massive earthquake struck Haiti in 2010.

“They’re not going to the U.S. because they’ll get deported,” Aceves says, explaining that they’ve been stuck in a sort of limbo for years now. “They’re waiting for a big miracle.”

Although church services for the week have concluded, the building’s cavernous sanctuary is alive with human activity. Women braid one another’s hair into cornrows in every corner. Small clusters of people sit chatting with one another on stacking chairs, mattresses, and whatever else they can find for seating. The walls are lined with mattresses—up in the balcony, too—and serve as impromptu living rooms for the shelter’s residents. Despite the crowded living conditions, laughter and warm chatter fill the air.

No one here has come directly from Haiti. They all left after the earthquake, seeking asylum in various South American countries. Most have come from Brazil, Venezuela, Colombia and Ecuador, and many are already proficient Spanish speakers.

Christopher Faustin and his wife, Rosenie, both 36, have been in Tijuana with their two-year-old daughter for about three months. They went to Brazil first, for four years, then to Ecuador.

“After the earthquake, life became very bad in Haiti, and we were trying to get a better life,” Faustin says. “We left Brazil in September 2014 because I have a brother-in-law in Orlando, Fla., who said life is better there. Unfortunately, we cannot go now because too many people are trying to cross the border.”

The Trump administration’s 120-day freeze on general refugee admissions has been a major stumbling block for asylum-seekers like Faustin. He says life is hard here in Tijuana, and it’s difficult to get a job. Aceves says that among the 4,500 or so Haitians living around the city, only about 300 have permission from the Mexican government to work. Even so, Faustin doesn’t want to cross the border without proper documentation.

“Our destination was not here in Mexico, but I think I’m going to stay here, try to get a job and live with my family,” he says.

Aceves says that Haitian immigrants have meanwhile begun to pile up in Tijuana, creating a problem for Mexican citizens who are also starved for jobs. He says the government has funding for refugee shelters, but finds creative ways to ensure that it doesn’t end up serving refugees. Just last month, he says, the government ordered all the Haitian refugees out of the shelters the same day it was supposed to distribute nearly $400,000 in aid to them.

“The money is there, but its not being given to the shelters,” he says. Government corruption is a major issue, according to Aceves.

Several miles away, in Las Carretas Canyon, another shelter houses another couple dozen Haitians. The neighborhood, with its paved streets and gated driveways, is more polished than Scorpio Canyon, but the refugees’ living situation is similar. Here, mattresses line the bare concrete block walls of a large, open room, where a single compact fluorescent lightbulb sheds its dim white glare.

Gertha Siméon, 42, is braiding the hair of 33-year-old Liseola Konér beneath the dangling bulb. Their trajectory after leaving Haiti was similar to Faustin’s. Siméon says most of this group left Brazil when the country’s economic crisis made living there untenable. She and her husband traveled to Chile, and then to Mexico, hoping to gain entry into the U.S. Siméon is a nurse, and hopes one day to ply her trade in North America.

“We have had a lot of struggles—sea, mountains, jungle,” she says in French. “Donald Trump doesn’t want to know anything about us, but he doesn’t know the suffering we’ve been through to get here. But he should not deport migrants, because we are hard workers.”

Siméon then offers her version of a refrain heard often during a journey along the border zone: that the United States, while still a desirable option for sanctuary, is not the only one.

“If I cannot go to the U.S., I will go to Canada,” she says. “Canada is my dream now.”

The Watchers

A white Chevy Tahoe cruises along the steel border fence, kicking a small cloud of dust into the midday sun. The Border Patrol agent behind the wheel catches a flash of green through the thick mesh as a man in a hiking vest scurries off into the brush on the Mexico side, a pair of bolt cutters in his left hand.

There’s not much the Border Patrol agents can do to apprehend this man. He’s in Mexico so he’s Mexico’s problem, says Joe Reyes, a public affairs officer with the Border Patrol’s El Paso office. In fact, agents don’t even bother calling their counterparts on the other side. Mexico doesn’t maintain a border security force the way the U.S. does, so by the time anyone official from the Mexican side showed up, if anyone showed up at all, the fence-cutter would be long gone.

A trio of Border Patrol agents squints after him through the tiny holes in the mesh, and surveys the damage he has done to the fence.

“A few more minutes and he’d have gotten through,” Reyes observes.

There’s nothing to do now but report the damage back to headquarters, which will send someone out to weld in a patch. If they can’t make it today, agents will keep an eye on the weak spot until a service crew can get there.

The job of Border Patrol agent on the U.S.-Mexico border can be tough. Agents patrol alone, five days a week, in 10-hour shifts, often miles away from another human being. Because the Border Patrol is a federal agency, there are myriad regulations to observe. There are rules of engagement not unlike those placed upon an occupying military force. And the ambient climate in southern Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, and California, where agents spend time outside, tracking, can be brutal—blazing hot during the day and freezing cold at night.

“It’s not easy—it’s shift work, so we have to work weekends and holidays,” Reyes says. “You miss a lot of those times when family and friends are getting together.”

And there are physical dangers associated with the job.

“What we encounter more than anything is people throwing rocks,” he says. “An agent was hit with a rock not too long ago and had to get 42 stitches in his head.”

Reyes took the traditional route into the border patrol, serving in the army for six years before joining. Oscar Cervantes, who is riding with us, is also on the El Paso sector’s public affairs team. He joined the Border Patrol after college. Like all border patrol agents, both men have served “on the line,” as they call patrolling the border, and are currently on a public affairs rotation. When public affairs duty wraps up after a year or two, they’ll be back out on patrol.

“I like what I do,” Cervantes says. “We used to play cops and robbers when I was a kid—I was always the cop.”

Border Patrol, which falls under the jurisdiction of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, has more than 21,000 agents in its ranks. Nearly 90 percent are stationed along the U.S.-Mexico border. The rest are spread along the 5,525-mile border with Canada and select locations on the Gulf Coast.

The agency’s 125,500-square-mile El Paso sector is one of the smaller sections, covering about 268 miles of the border with close to 2,400 agents and a roughly 1,600-vehicle fleet. Reyes explains that, aside from their trucks, agents rely upon a series of camera towers and sensors and, further inland, checkpoints to help apprehend those who cross the border illegally. Reyes says there are a few other choice gadgets in use, too, including truck-mounted infrared cameras. Improved cameras, designed so that the casual observer can’t tell which way they’re pointed, have been installed on some of the towers.

“All this technology is great, but if the cameras are down, we’ll go back to what we know, and that’s tracking,” Reyes says. “Our latest greatest technology is three old tires dragged behind a truck.”

Thanks to the dry climate along most of the border, pulling a rig made from used tires behind a truck smoothens out the dust, making it easy to see fresh footprints. But glancing through the fence, we see a large yellow sponge laying on the ground, which Reyes says coyotes, migrants and drug mules strap to their shoes—sometimes they use old carpet—to avoid leaving prints.

“The coyotes and the cartels are very innovative,” he says with sincerity.

Another low-tech tool used by agents is conversation. If an agent sees someone suspicious, Reyes says, he or she will strike up a conversation. Ranchers and others who own property on the border are useful allies—agents know their vehicles by sight and talk with them on a regular basis to get an idea what they’re seeing out in the field.

“We can’t profile,” Reyes says—there are laws against such practices—but “if we see someone who looks like they’ve just crossed the border, we’ll ask them simple questions and gauge their answers,” he says. “They don’t have to answer our questions, and that’s fine. We just keep investigating the border.”

Many Border Patrol agents are of Mexican descent, if they aren’t immigrants themselves. Reyes is the grandson of Mexican immigrants, and Cervantes is a first-generation Mexican-American. Reyes says there’s a strong cultural connection between El Paso’s Mexican-American community and Juarez, which can make finding undocumented migrants difficult once they hit the streets of El Paso.

“If someone who jumps the fence makes it into the urban environment, they can blend in instantly,” Reyes says. The fence, he says, is not so much there to keep people out completely as much as to slow down would-be undocumented migrants, so that Border Patrol can catch them before they melt into the complex cityscape.

Both Reyes and Cervantes say they have a lot of compassion for migrants from poor countries. But they are both federal officials. Empathy can color how they approach the job, but like all federal law enforcement professions, the letter of the law is paramount.

“First and foremost, we take an oath to uphold the law,” Reyes says. “We do it humanely and compassionately.”

He points out that being arrested by the Border Patrol doesn’t necessarily mean someone will be deported. Granted, the efficacy of immigration courts and the rights given to undocumented migrants have been under scrutiny of late. But that’s why the justice system exists: to handle the legal end of border protection.

“Think of Border Patrol like the local police,” Reyes says. “We make an arrest based upon criminal history and other information, but other agencies, and the courts, ultimately make the decisions.”

Harry Hughes is on patrol for illegal immigrants in southern Arizona. He’s clad head-to-toe in Cold War-era woodland camouflage fatigues, and is the picture of preparedness: He wears a full-brimmed boonie hat, dark ballistic glasses, knee pads, and carries a military backpack kitted with provisions and a radio. He’s armed with a loaded, desert-tan AR-15 carbine. He looks less like a soldier than he does someone’s overenthusiastic dad headed for a gun-friendly Boy Scout camporee.

“I meet tourists and they don’t seem too alarmed by me,” he says. “Arizona is an open-carry state, so it’s not really a big deal.”

We’re about 65 miles north of the border, but Hughes says this is a prime migration corridor—particularly for migrants running drugs for the cartels. You could call Hughes border militia, but that’s only partially true. He regularly attends National Socialist Movement rallies around the country, and although the group is clear that it regards America’s European—that is, white—heritage as sacrosanct, it is not directly involved with any border militias. Hughes says more people showed up for immigration patrols in the past. Two other white nationalists were supposed to have joined this overnight camping trip-slash-patrol, but they backed out. Hughes is the last man standing.

Other groups, like the Three Percent United Patriots, are more organized about militia patrols. On the whole, though, border militias don’t seem as hot as they were a few years ago. Before the trip, I reached out to Arizona Border Recon, but the group replied in an email that it had suspended operations and media access until later in the year. Hughes, though, was amenable to an impromptu Friday night patrol.

Originally from Johnstown, Pa., Hughes lives in Maricopa County, so it’s not much trouble for him to grab his AR-15 and some gear—Hughes loves gear, and has all the latest and greatest military-grade stuff—hop into his F-150, and set up camp in the Vekol Valley for a day or two. Others he patrols with usually come from father afield, he says. But they do occasionally find migrants.

“The coyotes that smuggle these people over here don’t care about them,” he says. “We have people stumble-bumming around out here for days because their guide ditched them.”

Although Hughes believes Latin American immigration to be harmful to America’s traditional demographic, he says he feels genuine compassion for poor migrants doing what they can to find a better life. But at the end of the day, he says he wants to help the government enforce its laws by being its volunteer eyes and ears.

“I respect their resourcefulness, but I want them prosecuted,” he says. “I feel bad for them, but on the other hand, I can’t imagine abandoning my country and turning my back on my people.”

After a evening spent sitting in a folding camp chair beside a mesquite wood campfire, Hughes crawls into a U.S. Marine Corps field tent that he bought on the internet for some sleep. In the morning, he rises early to boil coffee on the tailgate of his pickup.

Then, the patrol begins. Assuming the standard military patrol position—eyes up, rifle muzzle down—Hughes leads us along a dusty trail, where we eventually wander across a dry wash. Yellow flowers grow along its banks, and he stops, pulls them toward his nose and takes a sniff. When we encounter some tire ruts further along, he pauses to examine them, kicking at the dirt with the toe of one of his desert combat boots.

“Looks like someone got stuck in a rental car,” he observes.

We continue on to a cluster of abandoned ranch buildings where he thinks migrants could be hiding. Also, he likes the scenery here. As we investigate what looks like an old animal enclosure, Hughes shares his views on the migrants coming to the U.S.

“We’re dealing with people who are less educated than we are,” he says. “They’re superstitious. They believe in the Chupa Cabra and spirit animals.”

One time, he found a body out here. The hands, feet and vertebrae were intact, and the skull was still there, but the rest had been picked clean. Another time, a migrant with a dead cell phone battery emerged from the brush onto his campsite, where he and some friends were sitting around a fire, cooking dinner. He says they gave the guy some water and promised him food while one of them called Border Patrol.

Today, however, we don’t find any tracks. No famished migrants stumble from the clumps of mesquite trees lining the dirt road. We don’t even encounter hikers or bird watchers. The desert, awash with vegetation and kissed by cloud-filtered sunlight, is tranquil.

“I think they know we’re here,” Hughes says.

Several dozen carpet shoes, the kind undocumented border crossers use to obscure their footprints as they hike through the desert, sit in two neat rows on the font porch of the Chiltons’ sprawling ranch house. Several humorous security signs—“Is there life after death? Trespass and find out”—are propped against the wall, next to the shoes.

Jim Chilton is a fifth-generation Arizona rancher. Wearing a white cowboy hat, jeans, a white button-down, a black leather riding vest and riding boots, he looks the part. Having grown up on a ranch north of Phoenix, he moved to Los Angeles to pursue a career in finance after graduating from Arizona State University. But he couldn’t stay away from the ranching life forever, and used some of the proceeds from a successful business to get back into it part-time. He and his wife, Sue, bought this ranch house in 1987. When he retired from finance, in 2008, he transitioned to ranching full-time.

“I’m not rich, but I’m well off,” he explains. “I’m like the old cowboy who won a million dollars and when asked what he’ll do with all the money, says, ‘Well, I’m gonna keep ranchin’ ‘til it’s all gone.’”

Most of Chilton’s sprawling, 50,000-acre ranch is leased from the federal government. A few miles of its southern edge shares a border with Mexico. Over the years, the land he and his cowboys work along with a few neighboring ranches has become a corridor for illegal immigration and drug-smuggling. Chilton says there are about 200 impromptu pedestrian trails on his ranch; he keeps the carpet shoes and black water bottles migrants leave behind as physical evidence that the area is, in fact, an immigration artery.

To show us how easy it is to cross the border on foot here, Chilton drives us there in his white Ford F-250, a Ruger Mini 14 carbine jammed between the seats. It takes nearly an hour crawling along rough dirt roads to reach our destination. Along the way, we see scenery worthy of postcards—red-orange flowers blooming amid green scrub; towering sandstone formations presiding over rows of hills and ridges; caramel and honey-brown cows lazily munching rough grass. At last, we arrive at the border. It’s nothing more than a barbed wire fence snaking its way up and down a series of steep hills. A dry wash at the bottom is studded with old railroad ties, but otherwise looks like a good place to cross. Chilton demonstrates by dropping to his hands and knees and wriggling under the lowest strand of barbed wire, still clutching his rifle.

Back at the ranch house, where Sue serves us ranch beans and cowboy coffee in an elegant dining room, Chilton shows us footage from three motion-activated cameras posted around the property. He’s seen hundreds of migrants cross the ranch, most of them dressed in camouflage and carrying backpacks the size and shape of hay bails. He says the cartels have radio-equipped lookouts perched on mountaintops around the area so that migrants can choose routes away from ranchers and Border Patrol agents. But despite the surveillance equipment, Chilton is just as eager to avoid the trespassers.

“When we see border crossers, we go the other way, quickly,” he says. “I just try and mind my own business and hope that the cartel scouts route their people around me.”

Although Chilton does his best to steer clear of migrants and traffickers, there are tacit reminders of their coexistence everywhere on the ranch. Signs in English and Spanish ask that pedestrians please close gates when they pass through them. Chilton puts out water for migrants, in case they’re dehydrated after trekking across the inhospitable desert.

“If we find someone who’s desperate and needs help, we’ll help them,” he says, adding that such hospitality was also once extended to a tattooed MS13 gang member who showed up on his front porch. Sue stopped going out on the ranch alone after that. “It’s a humanitarian crisis, is what it is.”

Chilton has some ideas about how to make the border secure, but they aren’t like anything the federal government has going now. In his opinion, a fence would be useless without agents able to respond when someone gets over, under, or around it. Pointing out how long it took for us to drive the 12 miles from his house to the border, he wonders how the Border Patrol can enforce a border it can’t reach in a timely manner.

“They can’t patrol this area from Tucson,” he says. “We’ve ceded this area to the cartels.”

Chilton suggests that military-style forward operating bases be built on the border. Agents could stay there for a week or two while on patrol, he says, then rotate back to town for their days off.

“If you build a wall and hang out in Tucson, well, [former Homeland Security] Secretary [Janet] Napolitano said it best: ‘Show me a 12-foot wall and I’ll show you a guy with a 13-foot ladder,’” he says. “If the Border Patrol put its people along the international boundary, they’d have 27 people per mile.”

As it is, it can take Border Patrol agents hours to reach parts of the border only accessible by rough ranch roads—if there are roads at all. Chilton says he found a large bale of marijuana on his ranch a few years back and, remembering the Border Patrol’s warning not to pull out his cell phone while in view of the cartels’ mountaintop lookouts—one of his neighbors did and was gunned down in front of his home after calling in a drug find—Chilton waited until he was back at his house to call the authorities. By then, he says it was time for a shift change, and it was several hours before an agent could come investigate. The bale was still there hours later, though. The Chiltons say the indiscreet manner in which the drugs were retrieved had them fearing for their lives over the next few months.

The Chiltons voted for Donald Trump, and agree with his plan to build a wall, but Chilton thinks it will be ineffective without better patrolling.

“In a football game, do you put your players 10 yards behind the line of scrimmage?” he asks. “No, you don’t.”

The Helpers

It’s a Tuesday just before noon. Sister Denise LaRock parks her car in a lot next to the Greyhound bus station in downtown San Antonio. She pulls several backpacks stuffed with snacks and personal hygiene items donated by a local church group from the trunk and walks into the building. Paper tags affixed to the backpacks with thin pieces of wire read, “Bienvenidos al USA.” Welcome to the USA.

When migrants are released from detention centers near San Antonio they are brought by bus to the Greyhound station. Staff from the Refugee And Immigrant Center For Education And Legal Services (RAICES), an organization that helps migrants with shelter, legal aid and supplies, said that until recently, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) would bring them directly to the shelter. That the practice was halted in December. Now, volunteers check the bus station every day to make sure they don’t miss anyone.

Inside, an eclectic cast of characters sits on metal seats and mills around between the boarding area and cafeteria. LaRock, a fiftyish woman with short gray hair, a friendly face, and blue eyes framed by rimless glasses, sets up her bags on a row of seats in a dark corner of the waiting area below a television mounted near the ceiling. Dressed in jeans and a sweatshirt, LaRock keeps an eye out for migrants, scanning the door in case any should come in.

She doesn’t have to wait long. Five women and seven children, carrying their bright yellow government-issue tote bags, file in through the automatic door. The fathers aren’t around. When these families are caught, or turn themselves in seeking asylum, the men, including boys older than 10, are separated from the women and girls, and are usually confined for longer than the rest of the family.

The women are of different colors and complexions, all coming from either Honduras or El Salvador. Sister Denise, an Anglo, wastes no time using her relatively new Spanish language skills to break the ice. Her community—that’s the word she and her fellow nuns at the Daughters of Charity of St. Vincent de Paul use to describe their order—recently sent her to Miami for three months to study the language. Now, she can speak well enough to communicate with the people she’s trying to help.

The kids are handed bags of potato chips and Coca-Cola in paper cups from the soda fountain, and they devour the treats. Their initial apprehension disappears, and before long, they’re kids again—running around, shrieking, laughing.

One of the migrants in today’s group is a petite, 22-year-old Salvadoran woman named Melissa, who withholds her surname to avoid potential problems with immigration officials. She wears jeans and a bright pink T-shirt, and her black hair is pulled into a pair of neat, tight French braids. Her chubby-cheeked, three-year-old daughter Camila smiles and asks questions softly in Spanish.

Melissa, through an interpreter, recounts the circumstances that led her family to leave El Salvador. Her husband, José, was a police officer; gang members threatened to kill him and his family. They fled.

To pay the coyotes who would sneak them out of El Salvador, and then onward by bus, car, and commercial truck through Guatemala and Mexico, they took a $7,000 loan from a bank, borrowed another $1,000 from a friend, and scratched together the remaining $2,000 themselves. For much of the journey they rode in a truck trailer, often at night, when it was cold in the trailer. During the day, they sometimes hid in safe houses, spending four days in one location—two of those without food. The trip to the U.S. border lasted about 15 days in all.

Melissa says she and her family crossed the Rio Grande into the U.S. in a small boat, near McAllen, Texas. They walked for about 15 minutes before coming across a Border Patrol agent. They were all sent to a hielera—one of the air-conditioned “coolers” where ICE keeps new detainees.

José was held for about four hours before being separated from his family and, eventually, sent to the Port Isabel Service Detention Center, in Los Fresnos, Texas, only a few miles from South Padre Island where college students—and some coyotes—flock for spring break beach parties every year.

Melissa and Camila spent two days in the hielera. Both had scabies and so were isolated from other detainees. Melissa said her daughter was shaking from the cold, and was given only a Mylar survival sheet for warmth. They were fed sandwiches and juice four times a day. Although the sandwich bread had been thawed, she said, the meat was still frozen.

Then, they were sent to a perrera, or “kennel”: a caged enclosure Melissa says was little better than the hielera. When she and Camila began to doze off, immigration officials would bang things and make loud noises to keep them awake.

“They didn’t allow us to sleep,” she says.

(RAICES staff members later explained to me that the so-called hielera and perrera holding cells ICE uses to house asylum seekers during their first several days—usually a bare concrete block room or a cyclone fence cage within a large warehouse—are purposefully kept cold and bright. They have limited toilet facilities and, with multiple migrants per cell, no privacy. Fluorescent lights emit a sterile glare 24 hours a day, and the concrete floor is the only surface for resting.)

Melissa and Camila were finally sent to the Karnes County Residential Center to await Melissa’s Credible Fear Interview, or CFI. During their 12-day stay, Melissa cleaned bathrooms and windows, for which she was paid $3 per day. She used the money to purchase personal items at the facility’s commissary. Her daughter was in daycare provided by the facility.

“It didn’t feel like a prison,” she says, “but there was a lot of order and discipline.”

Karnes staffers didn’t explain much regarding her rights, or what she needed to do to prepare for her CFI, Melissa says, but RAICES attorneys did.

As Melissa and Camila sit in the San Antonio bus station, a tiny red light blinks from a black plastic bracelet attached to Melissa’s ankle. She and Camila are on their way to her grandmother’s house, in Las Vegas. Eventually, an immigration court will make a decision on her case and, pending a favorable outcome, the bracelet will be removed. Melissa says that because her husband was a police officer, she feels confident that they have a strong case for staying—but says the stakes couldn’t be higher.

“If we are sent back to El Salvador, we will be killed in less than a week,” she says.

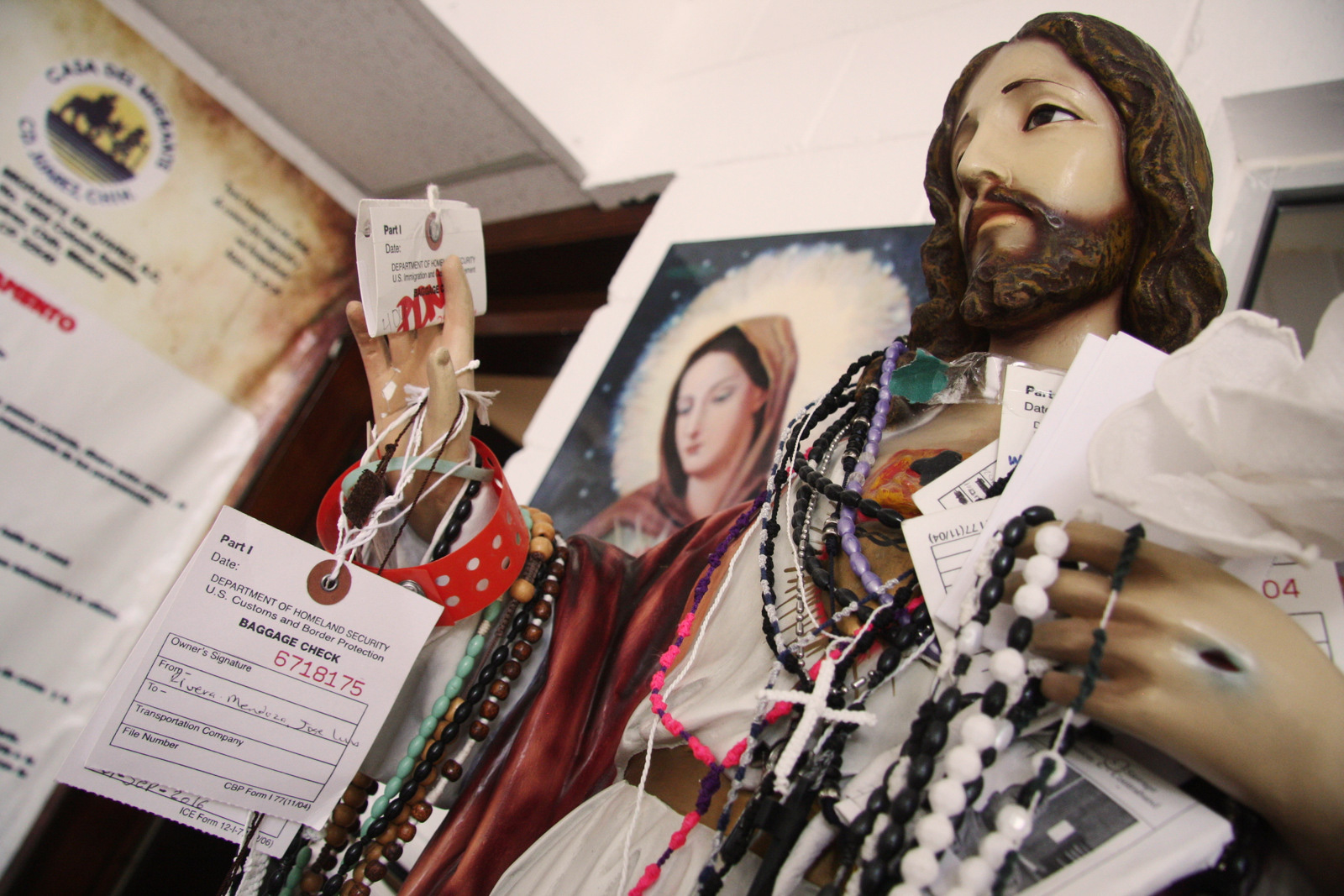

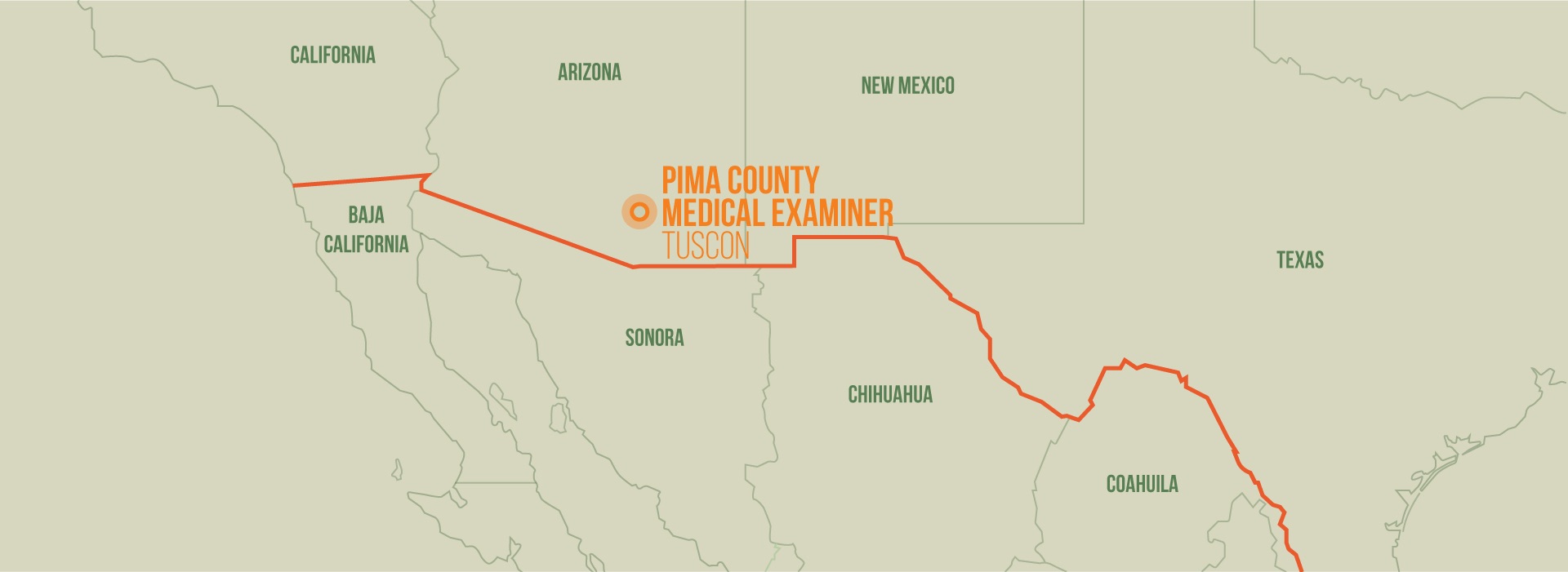

Dr. Gregory Hess, the Pima County medical examiner, opens one of the red-painted steel lockers in the facility’s property room. Inside, several plastic sheaths hold the belongings of migrants whose remains were found in the Sonoran desert: a toothbrush; a Mexican ID; a belt buckle; shoelaces; a braided rosary chain; eyeglasses; 60 pesos. Each sheath bears a decedent’s name. Each locker has been set aside for remains found in a particular year.

“The number one cause of death among migrants is exposure—hypothermia or hyperthermia, often coupled with dehydration,” Hess says, noting that the remains his team examines are often badly decomposed.

Crossing the Sonoran desert is risky business. If the objective is to evade capture by federal immigration authorities, the trek, usually made on foot, can take about six days. Water is heavy to carry, so bringing enough is difficult. The climate is extreme. During the day when the sun is shining—and it is almost always sunny here—the temperature often tops 100 degrees, and can climb as high as 118. After nightfall, the temperature can drop to 60 degrees. Weather that could have caused heat stroke quickly turns into an agent of hypothermia.

“The human body needs to maintain a certain temperature to maintain cellular processes,” Hess explains. “People become disoriented and lethargic as the body begins to shut down.”

In 2015, the Pima county medical examiner’s office processed 130 remains collected in the desert. Last year, there were 156. As of April 1 of this year, it had already processed 41. Most of them were Mexican nationals, Hess says; asylum-seeking migrants from Central American countries tend to cross where they know they’ll be able to turn themselves over to immigration officers.

“Since 2001, we’ve identified 65 percent of the roughly 2,500 border crosser remains law enforcement has found,” Hess says, explaining that his agency’s death numbers loosely follow apprehension statistics. “That’s still about 900 people who haven’t been identified.”

Hess says that the border fences built in and around towns and cities over the past decade have forced undocumented migrants to cross the border through more remote stretches of desert. Compared with crossing into a populated area where they can disappear into a crowd, trekking through the desert takes longer and is far more dangerous. Getting lost is a distinct possibility, and there’s no help if coyotes or other migrants become violent.

“Clearly there are factors that drive people to move from one place to another,” he says. “Sometimes its economic, other times they’re fleeing violence. But the funneling effect is responsible for the deaths we have here in Arizona.”

With the help of 34 rescue beacons stationed around the desert, the Border Patrol rescued 364 people last year. Distressed trans-desert pedestrians are invited—in English, Spanish and O’odham, a Uto-Aztecan language spoken in southern Arizona and northern Sonora, Mexico—to press a red button on the 30-foot-tall communication towers to initiate rescue. Unfortunately, not everyone finds or uses them.

Once remains arrive at the medical examiner’s office, the painstaking work of identification begins. Some remains arrive fully fleshed, but often the office will receive only a single bone—usually the femur or another large bone. The harsh desert climate works quickly on human remains, as do scavengers. Identification becomes increasingly difficult the less there is to work with. Hess says they take DNA samples, but unless someone is looking for the decedent, or that person was involved in a crime that required DNA testing, not much will come of it.

The examination room is small and packed with bones of various colors. A sickly odor of chemicals and decomposition hangs in the air. On one side, a full skeleton still stained brown and black from disintegrating flesh is laid out on a sheet. On the other side are a few skulls and some jawbones.

Even with partial remains, there are ways to deduce where the decedent may have come from. The femur is a good indicator of height. Indigenous people, and many from Central America, tend to have short femurs. Hip bones and rib joints help examiners determine age. Broken teeth and bullet holes tell a story of violence. Personal belongings can be telling, too, although documents like birth certificates and ID cards can’t be assumed to be real.

The main reason for identifying a decedent is to make sure that they can be found if family members are searching for them. That’s why Hess holds on to remains until his team has exhausted all possibilities of identifying the subject. A bone found in 2005 could be reunited with more skeletal remains several years later. Hess says there are currently about 15,000 remains housed at the facility.

“What you don’t want to do is bury someone under the incorrect name, because then they’re lost forever,” Hess says.

Even if a family is looking for someone they knew was going to cross during a certain time window, they might not reach out to the medical examiner’s office for more information—in many cases they, too, are undocumented migrants, and want to steer clear of any type of authority.

Although the medical examiner’s office does what it can to connect families with the remains of their deceased loved ones, it doesn’t have the capability to reach out to Spanish-speaking families distrustful of government agencies. That’s where the Colibri Center for Human Rights, which maintains an office in the medical examiner’s building, comes into play.

“We do what we can to fill in the missing pieces in the puzzle,” says Reyna Araibi, a project manager for the center’s Missing Immigrant Project. “Our database has more than 2,500 active missing persons reports from family members who know their person was crossing the border.”

Families searching for their missing loved ones are scattered all across the U.S. and Latin America. The biggest challenge to helping them, Araibi says, is getting the word out that Colibri is there to help. Most migrants come from very poor families, often from the most marginalized parts of society, indigenous communities in particular.

“They have very little in life, and they have very little in death,” she says, explaining the lack of resources poor people face when looking for lost loved ones. “We’re trying to be the most centralized place for people to go to find out about missing migrants.”

As spring builds into summer and daytime temperatures again climb above 100 degrees, Hess and Araibi know they’ll have their work cut out for them. Although Border Patrol apprehensions are down in the wake of President Trump’s tough words toward undocumented immigrants, Araibi says militarizing the border won’t solve the illegal immigration problem.

“Deterrence doesn’t work because deterrence doesn’t address the reasons people were coming here in the first place,” she says. “The wall is never going to address what Trump wants it to address. There’s still a great demand for labor in the U.S., and there’s still poverty and violence in Central America.”

The United States

It’s sunset at Shelby Park, the patch of green nestled between the city’s flea market and the banks of the Rio Grande. The municipal recreation area is abuzz. A group of elementary school-aged girls play little league baseball on one of the baseball diamonds. On an adjacent field, older boys play soccer. Fishermen stand patiently by lines they’ve dropped into the Rio Grande, and couples stroll around the park’s edge, beneath the international bridge. The bright, colorful lights of the carnival rides that have been set up for the annual Friendship Festival wink as the light fades. The scene is one of idyllic calm, the bookend to a day in a wholesome small city.

Aside from the traffic-choked bridge—the delays are all on the inbound side—the only clue that this park is perched next to the international border is a black metal fence next to the flea market, several hundred yards north of the river. Completed in 2010, the fence separates Shelby Park and the municipal golf course from the rest of town, and stretches west for a few miles atop the bluffs flanking the flume.

“The federal government spent four to five million per mile on it,” Ramsey English Cantú, mayor of Eagle Pass, said of the fence. “That money can be better used at the ports of entry.”

At this spot on the border, the fence isn’t particularly imposing. At 14 feet, it’s tall enough to dissuade the casual intruder, but the way it’s built—with thin vertical metal bars set several inches apart—makes it easy for a physically fit climber to scale in seconds. Two large gates at Shelby Park are left open 24 hours a day, seven days a week, although U.S. Border Patrol agents are usually close by.

Back when construction on the fence finished, Border Patrol told the Austin America-Statesman that the fence allowed the agency’s Eagle Pass office to carry out its mission using 30 percent fewer agents than in the pre-fence days. The agency also reported seizing nearly double the value of illegal drugs that year. Others, including the mayor at the time, said the fence didn’t make much of a difference.

A little league coach wrapping up practice in Shelby Park tells us that he works for U.S. Customs and Border Protection, though he asked not to be identified. He says that most of the drugs come through the ports of entry on the city’s two international bridges, reinforcing Mayor Cantú’s assertion that the federal government’s money would be more effective if used to put more “boots on the ground.”

“The Border Patrol does an exceptional job in keeping our border safe, but I think there are other ways, other than a fence, that we could do that,” Cantú has said.

Although the border fence has been a presence in town for nearly a decade, recent furor over the concrete wall proposed by President Trump has renewed economic tensions between Eagle Pass and its neighbor to the south, Piedras Negras, in the Mexican state of Coahuila. Cantú explained that, like many adjacent border communities, the two cities are tied to one another both economically and, for most residents of Eagle Pass, by family bonds. But the declining value of the Mexican peso, longer lines to get across the U.S. border, and resentment brought about by the U.S. president’s anti-Mexico rhetoric, have combined to push many Mexican shoppers into staying home.

“The way Mr. Trump presented the wall idea was very disrespectful to Mexicans,” says Jaime Rodríguez, who works with his parents at Eagle Grocery, the market his family has owned for generations. “When he started talking about Mexico paying for the wall, they stopped shopping here.”

According to the most recent U.S. Census data, the population of Eagle Pass is nearly 96 percent Hispanic. Cantú is of Mexican descent, as is Rodríguez, who also holds dual citizenship. Immigration concerns do exist, but Rodríguez and others we talked with said the city’s residents tend to feel compassion for illegal migrants, even those who aren’t Mexican.

“In this community, ‘illegals’ are seen as people who come across the border to work,” Rodríguez said. “They’ll work for $40 a day in the blistering sun.”

Rodríguez said that while concern about drug smuggling does exist in Eagle Pass, residents of a posh neighborhood at the western edge of the city opposed a wall or extension of the existing fence on the grounds that it would obscure their view of the river.

Closer to town, the houses are smaller and packed closer together. Some are painted in the same bright colors common south of the border. Rodríguez stops at one of the houses next to the fence and knocks on the door. A face floats in the window, then disappears. The tatters of a vinyl window blind shamble down from a string and we hear footsteps receding deeper into the house.

Rodríguez knocks again, but there’s no answer. Eventually, a middle-aged woman appears at the clotheslines behind the house and speaks with us. Her name is Samaria—she withholds her last name—and she tells us in Spanish that it was probably her parents probably who came to the window, but that they’re afraid of visitors. Her family moved to the neighborhood from Mexico in 1985, when she was 10 years old. In 1996, her parents bought the house in which they now live. Samaria has an 11-year-old son and works as a driver for an adult day-care center.

“I don’t like the fence,” she said. “When we didn’t have it, we could walk down to the river. Now, we have to go way downtown.”

Evening sunlight filters through the fence bars into their backyard. Across the river, on the Mexico side, people are picnicking on the riverbank and swimming in the gently moving water; the only movement on the U.S. side is the occasional dust cloud that accompanies a Border Patrol truck.

“What I feel is happening is that people in Washington aren’t aware of what life is like on the border,” Rodríguez said.

Mayor Cantú said he’d like it if the president and members of Congress came to Eagle Pass, to see for themselves.

“Yes, there are issues that occur on the border,” he said. “But one, two, or even three issues aren’t going to paint a picture of the entire border.”

South Main Street in Del Rio, Texas, is quiet on a weekday morning.The pavement is clean and well maintained, and there are cars and trucks parked along both sides of the road. Many of the storefronts are empty, and look as though they have been for some time.

Benny’s Café is a reflection of the street outside. It’s clean, and its midcentury fixtures are in good repair, but everything inside—including a group of older men sitting at a table in the middle of the restaurant—evokes another era.

Among the men holding court in the back are Lee Weathersbee, who was on the city council for more than a decade; Gary Humphreys, who owns Humphrey’s Gun Shop, around the corner; and Darrell Davis, a rancher and superintendent of one of the area water districts. Their attitude toward the border, President Trump’s proposed wall, and immigration in general are about what one would expect from a group of older white men hanging out in a Texas diner during workday hours: they refer to illegal immigrants as “wets,” and are vocal in their support of the Trump administration’s policy proposals, despite the fact that Del Rio’s crime rate is well below the national average and there hasn’t been a murder in Del Rio in years.

“Back in the ‘50s, ‘60s and ‘70s, good people were coming up here for work,” Weathersbee says. “Then it started to change. Your house would get broken into, maybe your Jeep would get stolen. They started bringing bales of marijuana up from Mexico.”

Weathersbee says that since the federal government installed a border fence between Del Rio and its Mexican counterpart of Ciudad Acuña, Coahuila state, in 2006, immigration and drug trafficking have been re-routed toward the edges of the small city, where there is no fence.

“If they came through town, they would be difficult to catch,” he says. “Most of the population of Del Rio is Hispanic, and you can’t just stop everyone here because they’re Hispanic.”

Del Rio’s economy is centered around the federal government: Laughlin Air Force Base and the U.S. Border Patrol are its major employers. Across the river in Ciudad Acuña, maquiladoras—factories and assembly plants for companies taking advantage of lower wages and lack of unions—have been cranking out auto parts and other manufactured goods since the 1960s. Weathersbee says many plant managers live in Del Rio.

Carmen Meza, who owns Benny’s, doesn’t think a bigger structure will do much to affect the town, though her patrons are all decidedly pro-wall.

“People who jump the fence want to find work,” she says. “But not here on the border. They want to go to Dallas and Houston, because there are no jobs here.”

Before I leave, Weathersbee wants to show me his car, which is festooned with Trump campaign stickers. He explains that he isn’t anti-immigrant per se: his wife, a Palestinian Christian, came to the U.S. legally, and his son-in-law is of Mexican descent. But he’s worried about the future of America, and doesn’t like it when, say, Pope Francis speaks out against Trump’s wall.

“We’re tired of two-faced bastards like that telling us what to do,” he says. “When people ask me how bad it’s gotten in Del Rio, Texas, I tell them that any day, I expect a Mexican federal agent to knock on my front door and tell me to get out of his house.”

His friends guffaw. Weathersbee’s expression remains straight-faced and deadly serious.

This article originally appeared on TheDrive.com

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com