Do you have a question about history? Send us your question at history@time . com and you might find your answer in a future edition of Now You Know.

At TIME Magazine’s 20th anniversary dinner, in 1943, the magazine’s co-founder Henry Luce explained to those gathered that, while “the word ‘researcher’ is now a nation-wide symbol of a serious endeavor,” he and co-founder Briton Hadden had first started using the title as part of an inside joke for a drinking club. “Little did we realize that in our private jest we were inaugurating a modern female priesthood — the veritable vestal virgins whom levitous writers cajole in vain,” he said, “and managing editors learn humbly to appease.”

Luce’s audience nearly 75 years ago is not the only group to wonder about the origins of fact-checking in journalism, though the casual sexism of the 1940s would no longer fly. Today, especially amid concern over so-called “fake news” and at a time when it may seem inconceivable that checking an article would be possible without the Internet, it remains a natural question: How did this journalistic practice begin?

And, as it turns out, that story is closely linked to TIME’s past.

First Facts

In the years between 1923, when TIME’s first issue was published, and Luce’s speech, journalistic fact-checking had gone from a virtually unknown idea to standard practice at many American magazines. (These days, journalistic practices aren’t necessarily country-specific — Der Spiegel, for example, is known for having one of the world’s biggest fact-checking departments — but that wasn’t the case a century ago, and this particular kind of checking was an especially American phenomenon.)

Of course, well before any separate job of “fact-checker” existed, editors and reporters would have had their eyes out for errors — but it was around the turn of the 20th century, between the sensational yellow journalism of the 1890s and muckraking in the early 1900s, that the American journalism industry began to really focus on facts. The professionalization of the business included codifying ethics and creating professional organizations. And, as objective journalism caught on, ideals of accuracy and impartiality began to matter more than ever.

Publications in the first two decades of the 1900s did have operations intended to make them more accurate, like the “Bureau of Accuracy and Fair Play” that was started by Ralph Pulitzer, son of Joseph Pulitzer, and Isaac White at the New York World in 1913. The bureau was focused on complaints, looking “to correct carelessness and to stamp out fakes and fakers.” They would keep track of who was making errors, to catch repeat offenders. At the time, the idea was termed a “novel departure” by an industry publication, but it still concentrated on reprimands and apologies rather than preventing those errors from making it to print.

So, while it’s always difficult to say what the absolute first instance of something was, especially given that fact-checking is an internal function that doesn’t get much publicity when it’s done well, TIME emerged as a leader when the magazine began hiring people specifically to check articles for accuracy before publication. They weren’t called fact-checkers at first. (Though, appropriately enough, there was a period during which Luce and Hadden had considered calling their new magazine Facts.) The New Yorker — long renowned for its checking process — only started publishing in 1925, and didn’t start rigorous checking until 1927, according to Ben Yagoda’s About Town, following the publication of an egregiously inaccurate profile of the poet Edna St. Vincent Millay. Newsweek started in 1933.

Perhaps the earliest published use of the phrase “fact-checker” can be found in an ad for TIME in a 1938 issue of Colliers, which mentions the expansion of “its researchers and fact-checkers from ten to twenty-two.”

TIME’s first fact-checker was Nancy Ford. She’d worked at Woman’s Home Companion and in early 1923 was hired as a secretarial assistant as Luce and Hadden got their new publication started. Her job at first was to mark and clip interesting articles from newspapers for the magazine’s writers, but soon the task expanded to verifying basic dates, names and facts in completed TIME articles. Ford and her colleagues — all women — were encouraged to challenge the initially all-male staff of editors and writers, a must for the process to work. “The fun was that you could say what you thought,” she recalled in an oral history interview conducted in the 1950s, “and didn’t have to be respectful.”

Ford left after several grueling months of work, but the job didn’t end with her. At the end of the year there were three researchers.

Getting the Job Done

At first, the New York Public Library was Ford’s main source of information. She would call the Public Library’s Information Desk for “almost anything,” and was regularly there until it closed. And when it was time for the magazine to go to the printer each week, she and other necessary staff would pile into a taxi with their checking materials to head over to the press, on 11th Avenue (“Death Avenue” to the TIME staff). In the early days that meant lugging a copy of Who’s Who and the World Almanac, some of Hadden’s own books, a dictionary, a thesaurus and a Bible, along with relevant newspaper clippings. They stayed at the printer’s late into the night, hashing out rewrites, filling in holes and checking the last details. Ford “learned all the tricks of checking by phone from Eleventh Avenue,” and while the “girls,” as they were called, were usually dismissed earlier than the men, that often meant a 3:00 a.m. or 4:00 am departure.

Another of the fascinating resources on the early fact-checking process comes in an unusual format: poetry.

In the late 1920s, a Time Inc. employee named Edward D. Kennedy began to poke fun, in verse form, at the company’s inner workings. Many of his writings are still preserved in the company’s archives. For all their jabs, they also capture some of the difficult nature of the work, especially for the checkers, as well as the prevailing sexism of the time. Kennedy’s poem “The Genii” lampoons the particularities of TIME writers, who were known for their wordplay and boisterous style (Kennedy mimics it for the poem, opening with: “Who writes for TIME a genius is”) and includes a few nods to the female checkers tidying up after reckless writers: “If substance fails, if fact eludes, / Out of the air he picks it— / If obviously foolish, why / The girls will probably fix it.”

Another Kennedy poem parodies the extreme demands of TIME’s first managing editor, imagining him asking the researchers to “Call up God and ask if we can get a picture.”

An August 1927 memo from Hadden further reveals the details of the editorial workflow of the time, including the process of checking, who was responsible for what and when it should happen. The checker would put a dot over each word once she’d confirmed its accuracy — first red ones for facts checked from authoritative sources like reference books, then black dots when a fact was sourced to a newspaper and finally green dots for uncheckable words or ones that a checker accepted on the author’s authority. Facts were to be “red-checked” whenever possible. Anything that couldn’t be verified meant querying the author to hammer out the way a sentence should read, though later official guidelines mandated a demure or ladylike tone when doing so. “Carbons,” files containing copies of each version of the story and all the material used to check it, would be kept on file and handy for 13 weeks then filed away for at least a year. That terminology is still used at the magazine to this day.

Women’s Work

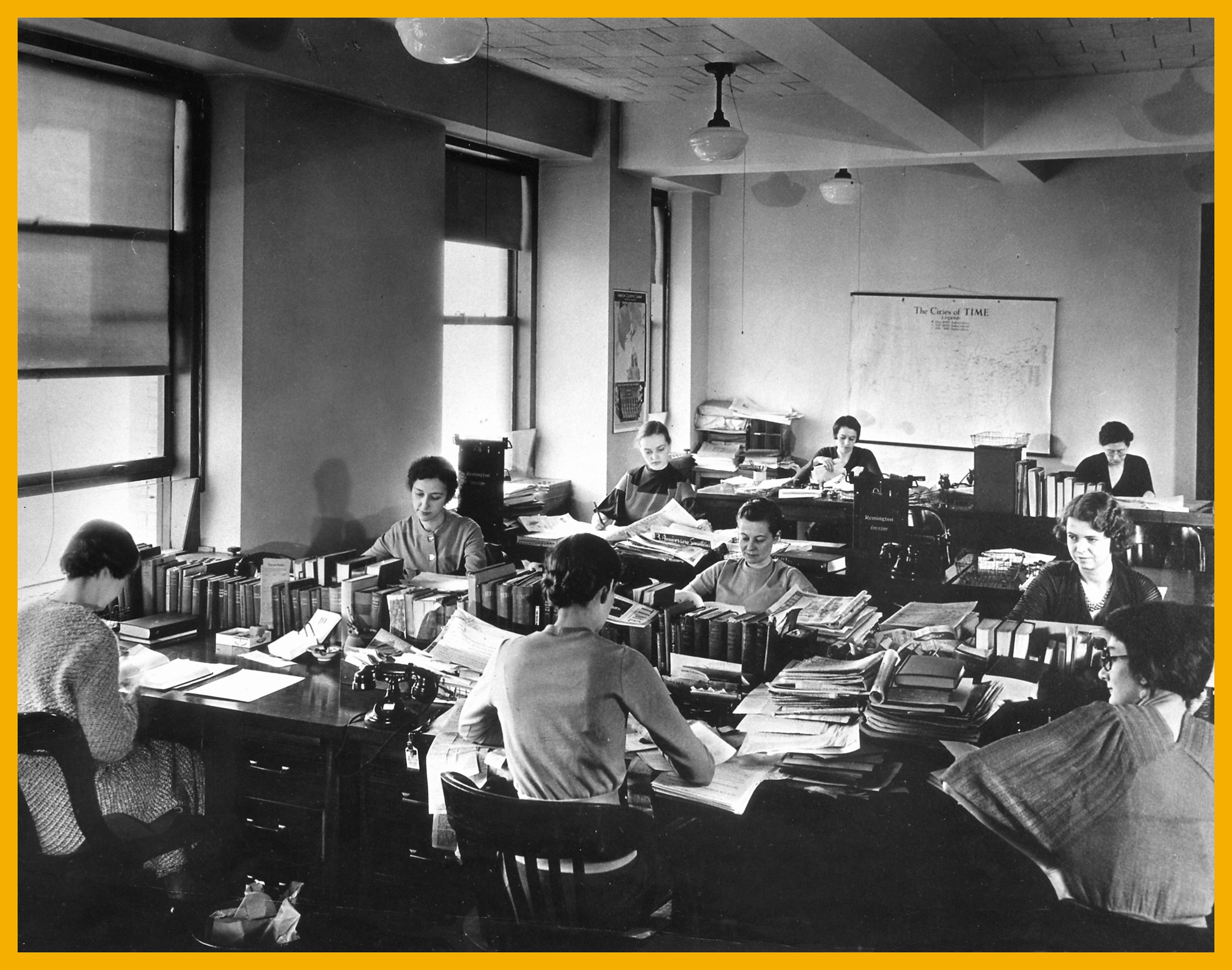

By the 1930s, becoming what was then simply called a “checker” was a relatively well-established next step for young women graduating from college. For example, Content Peckham (pronounced, as she would say, “like an adjective”) applied to TIME to be a researcher after graduating Bryn Mawr. “It was just the thing to do—everybody applied at TIME and Vogue,” she later recalled. She started as a science and medicine researcher in 1934, later becoming chief of research and the third woman to be on the masthead as a “senior editor.”

The women’s jobs were twofold. In the first part of the week they would do background research, finding interesting details and supporting material for articles that someone else would write. Peckham called it “the process of surrounding a story.” Once the article was written and edited, the researcher would circle back around and make sure every detail that made to the final version was correct. (Peckham noted, however, that training could be a matter of trial and error: when first she arrived, she was told about the dots system, but not how to actually check the words she was sorting.)

But, though the checkers’ jobs still centered on minute facts, the meaning of what it meant to be correct was shifting. According to Peckham, it was Patricia Divver — head of the TIME research department in the early 1940s — who made TIME’s fact-checking a more holistic, thorough process. “She was the first who taught her staff to worry not only about the correctness of the separate facts but whether what the facts said in aggregate added up to sense,” said Peckham.

That broad view meant increased responsibility and authority for the checkers. In addition, the coming of World War II put immense pressure on them to get breaking news right. For example, Germany invaded Poland on Sept. 1, 1939, a Friday, leaving the staff with nearly two dozen pages of text to check by that Monday. And if things went wrong, no matter where the error had come from, the checker was on the line. Weekly errors reports detailed the mistakes made, excoriating the (lower-paid) woman doing the checking rather than the male writer on the piece.

It was not until 1971, after the women at Newsweek filed a complaint with the Federal Equal Employment Opportunity Commission over the sex-segregation of the magazine’s jobs, that TIME’s research manual was re-written and researchers were renamed reporter-researchers. The job of fact-checking was subsequently opened to men, and by 1973 TIME had managed to hire and keep four men on the job.

Future Facts

In the decades that followed, for a variety of reasons, not least of which were the economic ones, the job shifted again. At some publications, the responsibility for accuracy began to shift primarily to the writers, as the number of jobs for people who were solely researchers or fact-checkers shrank. (TIME kept its fact-checking operation. Since the mid-1990s writers have been asked to take on checking responsibilities and checkers have been asked to do more reporting.)

But recently, a new sort of fact-checking has been the object of public attention, as articles and websites devoted to analyzing the factual accuracy of politicians’ statements have become their own genre. “What’s different is the mission,” says Lucas Graves, senior research fellow at Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism and author of a book on the subject, Deciding What’s True. The point of magazine checking is to prevent embarrassment and eliminate errors before a piece goes live, whereas the new political fact-checking usually devotes its attention to careful analysis of an error someone else has made.

“The emergence of political fact-checking is gradual, it has its roots in the 1980s but the genre has become much more codified and standardized over the last decade,” says Graves.

In the wake of the deceptive ads that populated 1988’s presidential race, “a lot of journalists felt they hadn’t done a very good job of covering that race, because they mostly let those claims go unchallenged,” he says. By the mid-2000s, hindsight on coverage of the run-up to the Iraq War compounded the feeling that it was necessary to check what politicians said.

The Internet became an important medium for news and non-journalists started using it to do their own public fact-checking. Fact-checking sites like Snopes (which originally focused on urban legends) and Smoking Gun started in the 1990s, and in 2003 the full-time political checking site FactCheck.org, a project of the Annenberg Public Policy Center of the University of Pennsylvania, started its operation. Soon others would follow them into the political fact-checking arena.

The new fact-checking is its own task, but it shares some of the essential beliefs that led the original “girls” of the 1920s and ’30s to make journalistic history.

“We don’t trust ourselves at all,” Leah Shanks Gordon, then head of TIME’s research staff, told the Chicago Tribune in 1983. “We must not assume that we know anything.” By the 1980s, the TIME staff were checking about 2.5 million words a year with only about 250 errors a year, mainly details like titles or dates.

Still, the idea that human error could be entirely eliminated wouldn’t pass muster with a good fact-checker, anyway.

On the occasion of TIME’s 25th anniversary in 1948, the editors wrote on the constantly moving target of fact-checking, and its impossibility: “All the facts relevant to more complex events, such as the devaluation of the franc, are infinite; they can’t be assembled and could not be understood if they were. The shortest or the longest news story is the result of selection. The selection is not, and cannot be ‘scientific’ or ‘objective.’ It is made by human beings who bring to the job their own personal experience and education, their own values. They make statements about facts. Those statements, invariably involve ideas.”

“All journalists (even the women at the well) select facts,” the editors continued. “The myth, or fad, of ‘objectivity’ tends to conceal the selection to kid the reader into a belief that he is being informed by an agency above human frailty or human interest.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com