For most of the past decade, New York City has struggled to solve a seemingly ridiculous problem: It spends about $100 million every year paying teachers not to teach. That’s how much it costs to operate the city’s so-called Absent Teacher Reserve pool, a limbo for about 800 educators entitled to full salary and benefits even though their positions were eliminated.

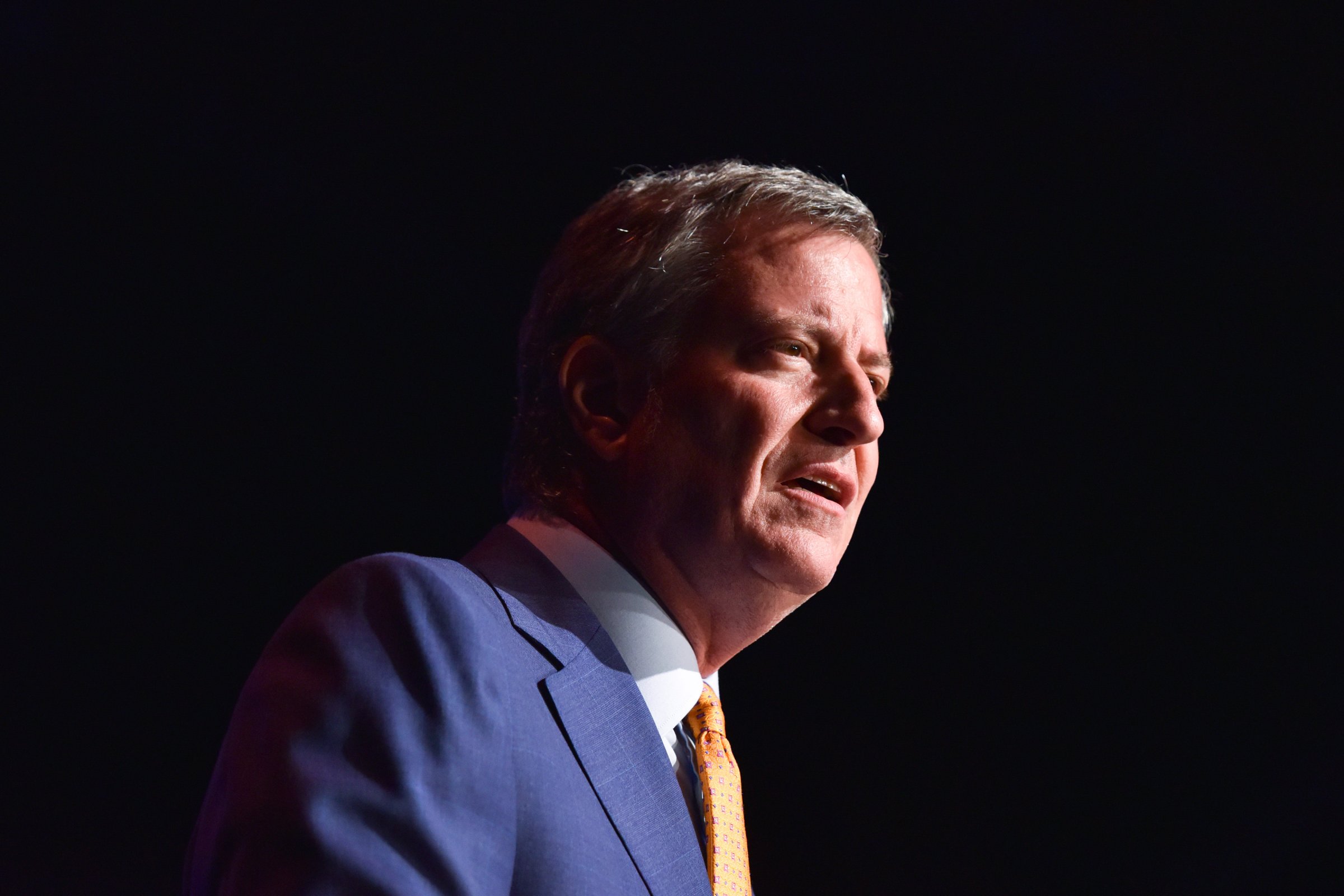

Now, in an effort to shrink the ATR pool and its cost, Mayor Bill de Blasio and Schools Chancellor Carmen Fariña are resurrecting one of the most harmful and discredited ideas in education policy: forced hiring of teachers. Any schools with open teaching positions this fall could be forced to take whichever ATR teachers city bureaucrats pluck from the pool, regardless of whether the teachers want the jobs or whether principals want to hire them.

This approach to hiring was the norm for decades in New York City, with disastrous consequences. Principals played an annual game of hiding open positions and strategically cutting existing ones to avoid having a teacher forced upon them. It created a dysfunctional culture that allowed low-performing teachers to bounce around the system for their entire careers — the infamous “dance of the lemons” that still plagues so many school districts across the country.

That’s why the city and the United Federation of Teachers agreed to end forced hiring once and for all in a landmark 2005 contract. (Full disclosure: I led the city’s team that negotiated the deal.) Ever since, the hiring process for teachers in New York City has looked a lot like the one you’d encounter in almost any other field: Teachers can apply for any open positions they want, and principals have final say on which candidates to hire. It’s called “mutual consent,” but it’s really just common sense.

Tens of thousands of teachers have used this process to find jobs in the city’s schools, including many who were once in the ATR pool. When ATR teachers struggle to find new jobs, there are often very good — albeit uncomfortable — reasons. Consider a few findings from a 2014 analysis of ATR teachers:

Another third had received unsatisfactory evaluation ratings.

More than half hadn’t held a regular classroom position for two or more years.

About 60% hadn’t applied for a single position in the previous year, suggesting they weren’t even trying to find a full-time job.

Another third had received unsatisfactory evaluation ratings.

More than half hadn’t held a regular classroom position for two or more years.

About 60% hadn’t applied for a single position in the previous year, suggesting they weren’t even trying to find a full-time job.

It’s no wonder principals nearly revolted the first time de Blasio and Farina floated forced ATR hiring three years ago, leading the chancellor to pledge that “there will be no forced placement of staff.”

Breaking that promise now would have only one possible result: Schools across the city would face an influx of teachers with records of poor performance. Students in lower-income neighborhoods, where teaching positions have historically been most difficult to fill, would be hit hardest. Principals would go back to hiding vacancies and would justifiably argue that they can’t be held accountable for student learning if they don’t get to pick their teams.

The city denies that the new ATR policy amounts to forced hiring because after one school year, principals will be allowed to send back any ATR teachers who earn low marks on their performance evaluation. But because only a tiny number of tenured teachers are ever dismissed for poor performance, any who fail this forced “tryout” will likely end up being foisted upon another group of students at another school the following year. More to the point, subjecting thousands of kids to ineffective teachers for even a year is simply unacceptable.

There’s a more responsible solution to the ATR problem, one that doesn’t hurt students or bring back the bad old days of forced hiring. The city and the teachers union should agree to reasonable time limits for teachers to remain in the ATR pool at full pay — six or 12 months, perhaps — after which those who can’t land one of the thousands of positions that open up across the city every year would be put on unpaid leave until a principal hires them based on merit. Districts like Chicago and Washington, D.C., already use this basic approach — one they negotiated with local chapters of the same union that represents teachers in New York City.

De Blasio and Fariña deserve credit for their persistence in trying to wind down the ATR pool and its drain on city resources. But putting the futures of countless kids in the hands of ineffective and even dangerous teachers is an unconscionably bad deal, no matter how many millions of dollars it saves. They should go back to the drawing board and make it clear that forced hiring is gone for good.

This article originally appeared on The74Million.org.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com