It’s impossible to put a price on the rocks and dirt brought back from the moon by the six Apollo landing missions — the rare case in which the word “priceless” applies literally. But one way to grasp the value of lunar samples is to compare them to something else we prize highly: gold. Over the course of history, about 425 million pounds of gold have been mined and refined. That’s 505,000 times more by weight than the 842 pounds of samples carried home from the moon. Gold currently trades at a per-ounce price of around $1,215. Using that as a benchmark and multiplying by scarcity, moon dirt should trade at over $614 million per ounce.

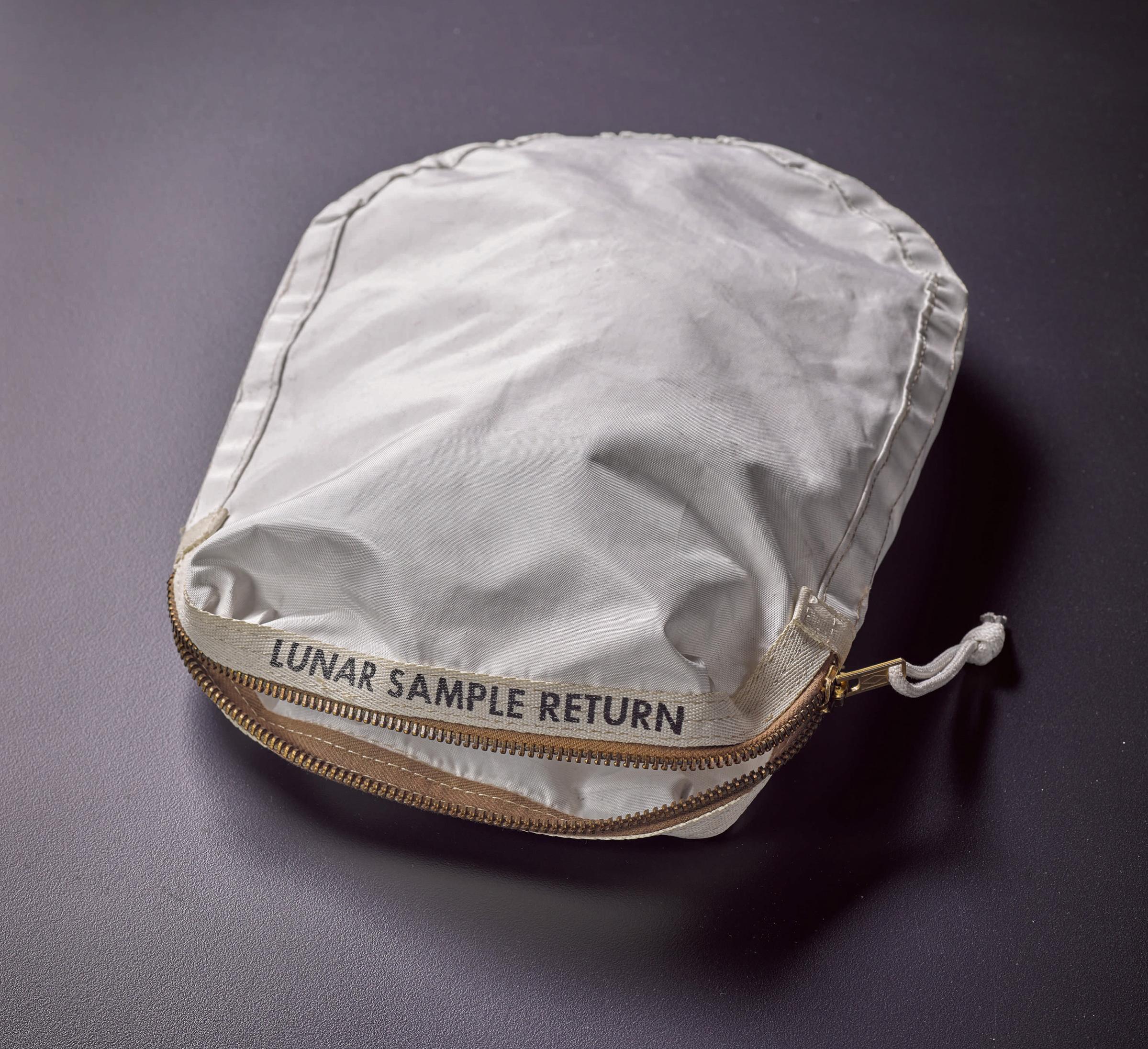

It’s not likely anyone will pay nearly that much for the lunar dust that will be sold at Sotheby’s during an auction of space artifacts on July 20 — the 48th anniversary of the first moon landing. There will hardly be an ounce of the stuff anyway, just a few grains and stains trapped in the fabric of a sample return bag carried home by the Apollo 11 crew. Still, that’s enough for the Sotheby’s appraisers to estimate a $2 million to $4 million sales range for the bag.

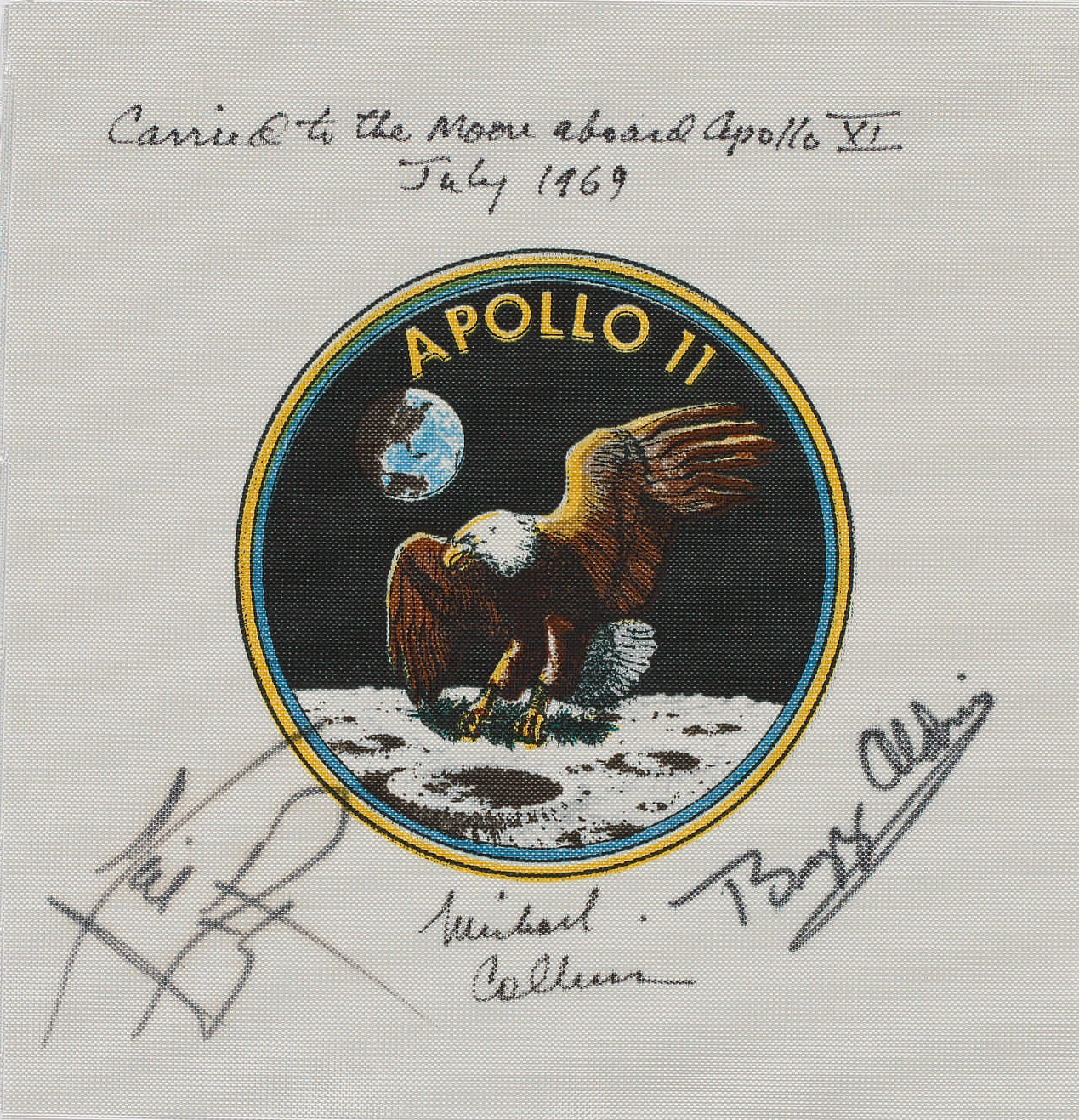

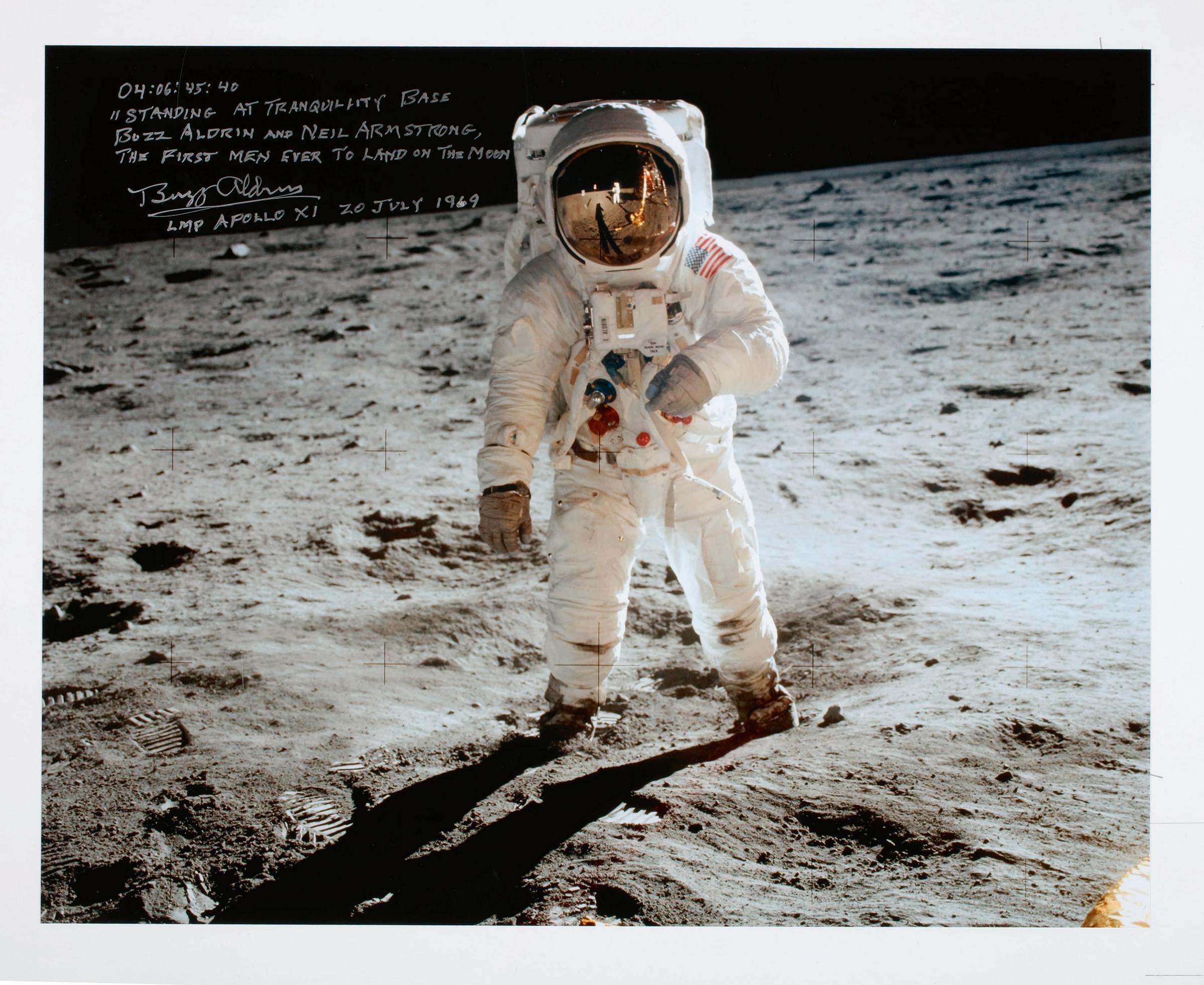

Space artifacts have that kind of effect on people, and the auction house is counting on a big pay day when the sample bag and the 172 other items being auctioned along with it go under the hammer. Some of the space merch on offer is, at least by cosmic standards, relatively commonplace stuff: the familiar photo of Buzz Aldrin standing on the Sea of Tranquility, but signed by Buzz himself; a patch from Apollo 11, but one that was actually carried on the spacecraft to the moon and back.

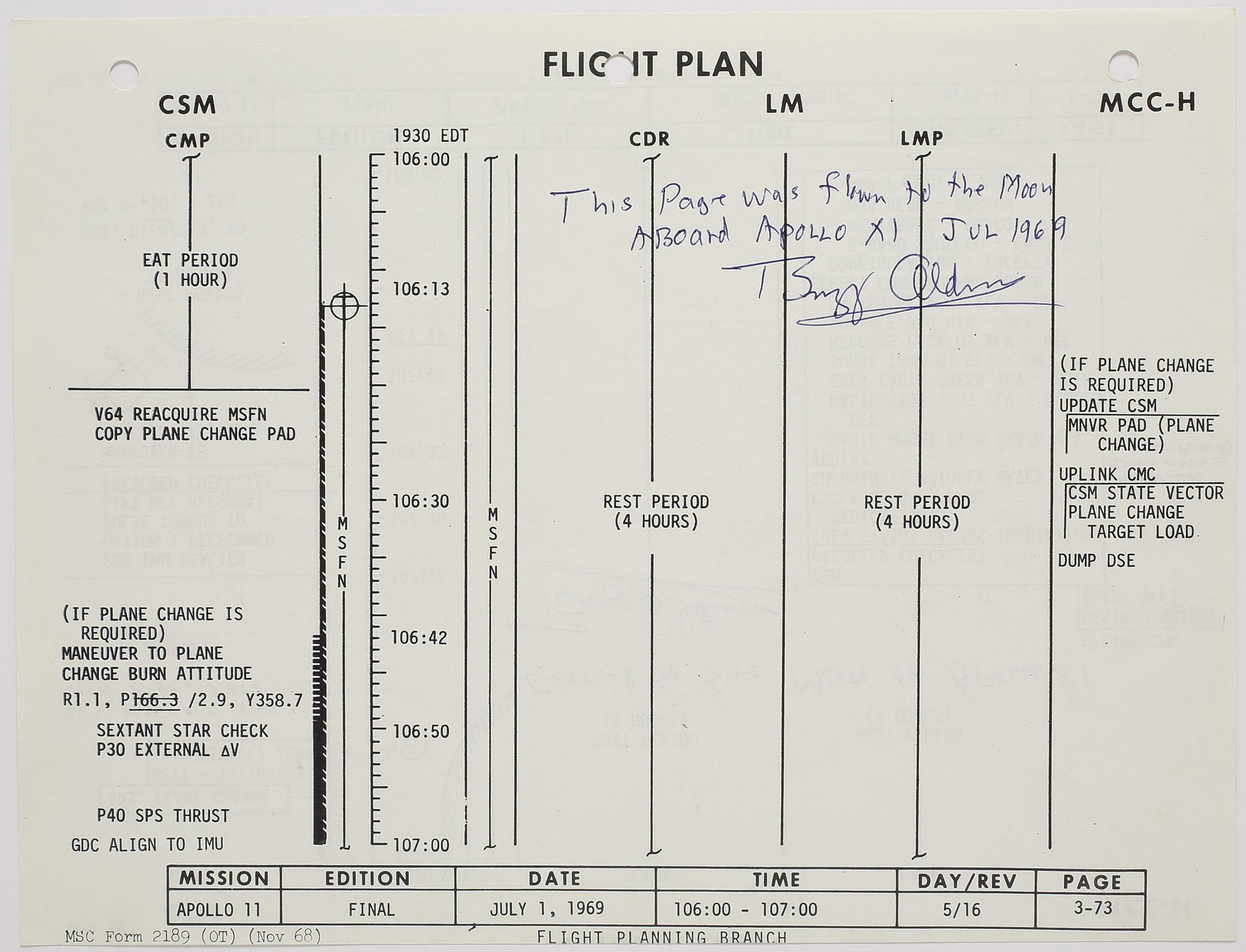

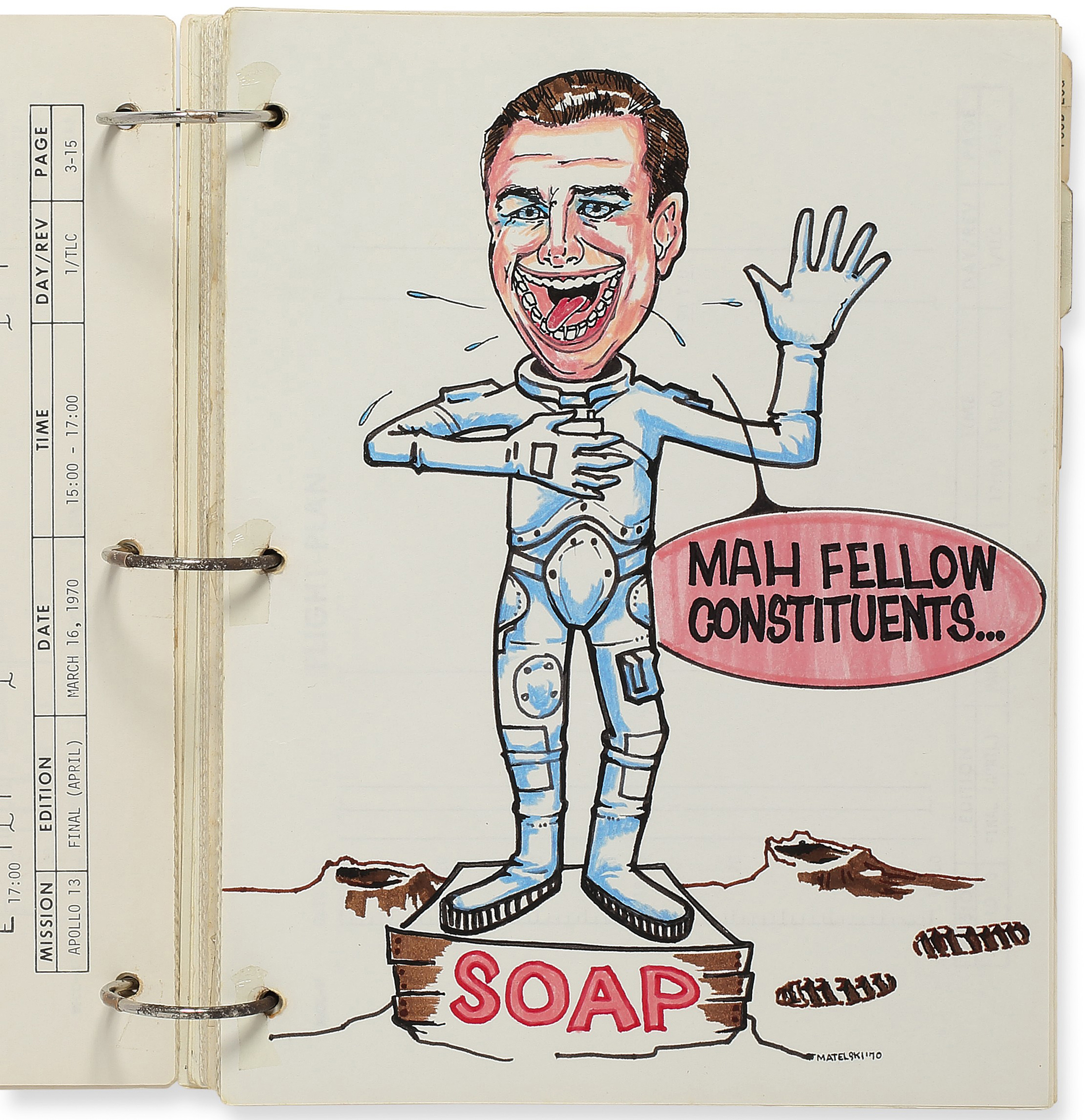

There are, too, actual pieces of actual ships — an altimeter cover flown aboard Apollo 9 and signed by mission commander Jim McDivitt, a pyrotechnic battery from the Apollo 11 lunar module. None of it looks any more glamorous than garage junk, except it’s garage junk that once left our planet and is therefore limned in a special light. Perhaps most evocative is the astronauts’ in-flight paperwork — a signed lunar map used by Apollo 8 navigator Jim Lovell when he and two crewmates became the first human beings to orbit the moon; a flight plan, filled with scribbled notes and workarounds, that Lovell and his Apollo 13 crew used 16 months later as they brought their crippled spacecraft back to Earth.

Artifacts are, by definition, backward looking things, and without a clear destination for America’s present-day space program, moon artifacts take on a special poignancy. The nation will surely find its way in space again, but the relics of the Apollo era — the first grand age of exploration — will likely never lose their value.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Jeffrey Kluger at jeffrey.kluger@time.com