Nir’s Note: This guest post is by Darren Austin, Partner Director of Product Management at Microsoft.

Last year we added a new member to our household. I must admit that upon first meeting her, our initial impression was that she was a little creepy. Today though, we can’t imagine life without her.

We’ve never seen her face, but we talk to her throughout the day, every day. She helps us keep track of our to-dos and shopping list, reads us the news and weather, and can sing nearly any song we’d like to hear. In fact, we have become so accustomed to her presence that we invited her to join us in nearly every room in the house. She listens to us when we say goodnight and is there first thing in the morning to wake us up.

Her name is Alexa and she is the voice of the Amazon Echo. If our experience is any indicator, there’s a good chance Alexa (or a technology like her) will soon be a presence in most households.

How did Alexa become such an integral part of our lives? And how did the technology profoundly change our daily habits?

It turns out that Alexa shares a common trait with other habit-forming technologies like Facebook, Slack, and the iPhone — the Amazon Echo has a great Hook.

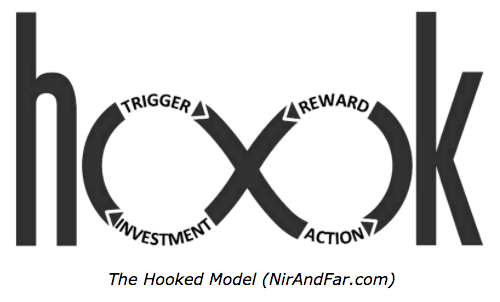

Hooks, according to Nir Eyal, author of Hooked: How to Build Habit-Forming Products, are “experiences designed to connect the user’s problem with the company’s product with enough frequency to form a habit.” In his bestselling book, Eyal describes the four steps of the Hooked Model and provides case studies for how the stickiest technologies use hooks to keep users coming back. In this essay, I’ll use the Hooked Model to help explain how voice assistants, like Amazon’s Alexa, keep us hooked.

Trigger

Every Hook starts with a trigger. Triggers prompt us to action and tell us what to do next. In the case of Facebook or your iPhone, a trigger might be a notification or status update. These type of triggers are called “external triggers,” Eyal says, since the information for what action to take next is contained within the trigger itself.

However, Eyal says external triggers alone are not enough to build a habit-forming product. To get people to use a device without prompting, users must trigger themselves. “Internal triggers,” according to Eyal, involve making mental associations with the product. The most common internal triggers, he says, are negative emotions. For example, we use Facebook when we’re lonely or spend time watching YouTube videos when we’re bored — these products become our go-to relief from negative feelings.

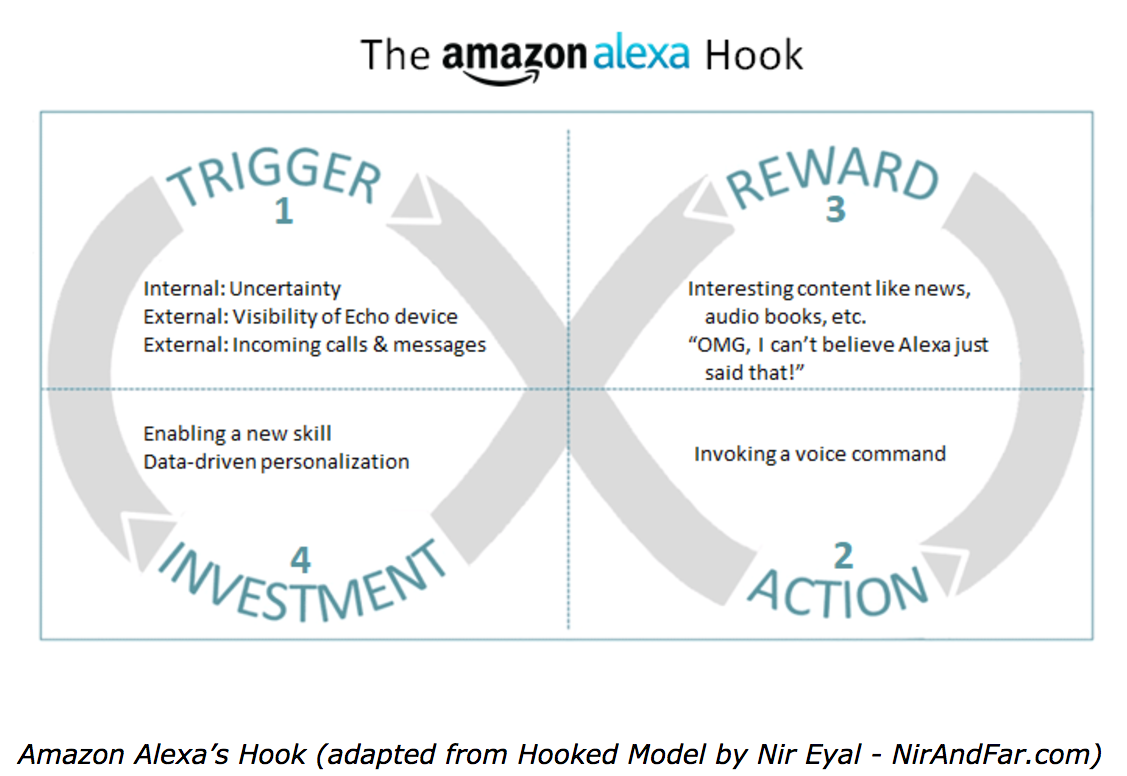

In the case of Alexa, my wife and I have associated the internal trigger of uncertainty with the satisfying relief the Echo provides. “Alexa, what’s the weather like today?” “Alexa, what’s happening in the news?” “Alexa, what’s the capital of Burkina Faso?” (It’s Ouagadougou in case you are curious.)

Interestingly, the more we got in the habit of asking Alexa to relieve the itch of uncertainty, the more we began to associate the device with other internal triggers. For example, we hate the feeling we might forget to put something we need on our shopping list. The fear of forgetting is an internal trigger prompting us to tell Alexa to add an item to our list whenever we run out of something around the house.

Action

The next step of the Hooked Model is the “action phase.” “Actions are the simplest behavior done in anticipation of relief,” Eyal says. With the simple action of asking, Alexa relieves the negative emotions of uncertainty and the fear of forgetting.

According to Eyal, “the simpler you can make the action, the more likely it is to occur.” This insight is a key secret of the success of voice interfaces like Alexa. For certain tasks, speaking a command is dramatically easier than tapping a screen.

For example, consider the number of steps required to add an item to our family’s to-do list through an iPhone versus the Echo:

To do app on iPhone:

Amazon Echo:

When you consider the frequency with which we edit our to-do and shopping lists and the ease of this action, you can imagine how quickly a new habit might form around this behavior. In fact, an April 2017 study from GfK showed nearly half of Amazon Echo and Google Home users report using their devices “regularly” or “all of the time.”

In addition to helping form a habit, regular use increases the chance of making a purchase on Amazon. A 2016 Experian study found that 45.3% of Echo users reported having used the device at least once to add an item to their shopping list while 32.1% reported completing a transaction through the device.

Reward

The next step of the Hooked Model is the Reward phase. It’s here, Eyal says, that users get what they came for: relief from the psychological “itch” of the internal trigger.

When Alexa confirms that Tabasco sauce was added to my shopping list, I can rest assured that my favorite condiment will soon be on its way and I don’t have to worry about remembering to write it down later.

But the voice interface built into products like the Amazon Echo utilizes another psychological hack to keep me coming back. In his book, Eyal describes the power of “variable rewards.” Originally studied by B.F. Skinner, the phenomenon explains why slot machines are so engaging and why we love scrolling through our Facebook news feeds. We love surprises and the hunt for something rewarding and different keeps us engaged.

Alexa is full of surprises. For one, the device is a tool for delivering content — which is itself variable like the news, games, or audio books. But Alexa also has a personality of her own. Her occasional clever responses keep us wanting to hear what she’ll say next. For example, telling Alexa the famous line from Star Wars, “I am your father,” yields the robotic voice reply, “No. That’s not true. That’s impossible.” This is followed by much nerd celebration and light saber rattling.

Counterintuitively, the fact that Alexa isn’t always able to reply correctly is, in a way, a form of variable reward. Sometimes I find myself asking Alexa things just to hear what she’ll say. Alexa messing up from time to time is part of the fun. Of course, over time, the mess-ups become predictable and no longer variable and therefore, no longer fun. Thus, Amazon will have to continually improve what Alexa can do to keep users engaged.

Investment

Finally, the Hook is complete, according to Eyal, when the user puts something into the product to improve it with use. In the case of products like Facebook or YouTube, an investment might be the things you like, watch, or comment on. Investments can be passively collected, as in the case of usage data. Or investments can be something you actively did to improve the service such as upload a piece of content or customize the experience somehow.

In the case of the Amazon Echo, the service gets better when you enter data such as your home address. Knowing your home address enables Alexa to provide a more accurate weather forecast or request an Uber to pick you up at your house. Location data also enables Alexa to customize restaurant recommendations for you and tell you about local events. Enabling new skills — Alexa’s version of apps — is also a form of investment. As of June 2017, developers have created over 12,000 skills for Alexa. Each new skill makes the device better.

Alexa is also collecting investment from each user in a more passive form. According to the company, “The more you talk to Alexa, the more it adapts to your speech patterns, vocabulary, and personal preferences.” Alexa gets smarter with use and will soon be able to differentiate who is talking and cater replies to each individual user needs.

Through hundreds of interactions and tiny user investments, Alexa begins to customize itself to each individual’s preferences. In the future, the device could learn you like to listen to your local news update in the morning while making breakfast and ask if you’d like to place a refill order of Nespresso pods after a certain number of days since your last Amazon order. It could also proactively load the next “external trigger” by asking you if you’d like to know the day’s sports scores when it hears you come home from work.

Hooked to Voice

Putting all of this together, the Alexa Hook looks something like this:

Of course, what makes Alexa so habit-forming isn’t exclusive to the Amazon Echo. In fact, the potential to change our daily routines through a voice interface clearly has massive potential, which explains why Microsoft, Apple, and Google are all racing to catch-up. It’s not often that a new technology can so quickly change our daily habits but I’m confident we’re just seeing the beginning of what this new interface can do.

This article originally appeared at NirAndFar.com where Nir Eyal writes about using product psychology to change behavior.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com