President Donald Trump may be the most brazen, but he is not the first politician to call reporters the enemy. One of the most famous and enduring complaints about journalists is they were largely responsible for losing the Vietnam War.

It is true that fairly early in that conflict many reporters believed the American war effort was failing. In fact, the distinguished journalist and editor Richard Harwood questioned General William Westmoreland’s body counts in a September 1967 Washington Post column entitled “The War Just Doesn’t Add Up.” This kind of writing set journalists squarely at odds with Westmoreland and his Military Advisory Command Vietnam (MACV), whose accounts were consistently upbeat.

It is also true that critical reports from the fighting fed growing opposition to the war at home, which worked to Hanoi’s benefit.

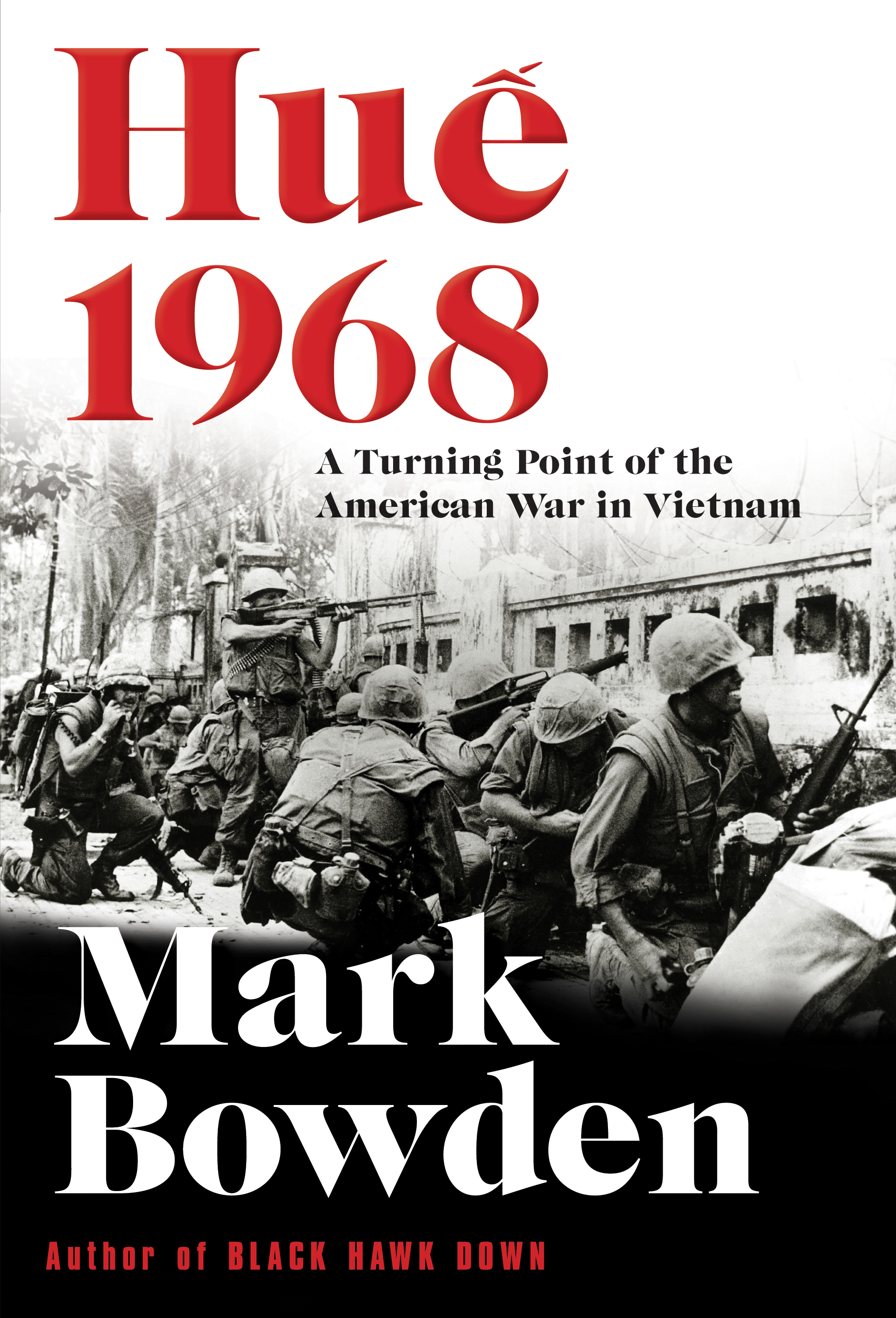

But were reporters responsible for this? Were they distorting success into failure, or was failure being distorted into victory by the military? The reporting of the Battle of Hue, the single bloodiest battle of that war, affords a good case study.

Early in the morning of January 31, 1968, a force of about 10,000 communist troops swiftly captured Hue, South Vietnam’s third largest city and the historical capital and cultural center of a formerly united Vietnam. A small American compound in the city’s southern half and a badly undermanned South Vietnamese military base in the northern half were the only parts of the city that were not taken, and these were both in danger of being overrun.

These facts are indisputable. They were detailed in a secret CIA report delivered to the MACV and to President Johnson that same day. The takeover of Hue was by far the biggest success of the Tet Offensive, which had kicked off all over South Vietnam at the same time. Fighting in Saigon and nearly a hundred other places shocked the American public, which had been repeatedly assured that enemy forces were relatively weak and scattered, and were being methodically crushed.

The takeover of Hue, in particular, ran directly counter to that narrative. The response of Westmoreland and his top commanders was to deny that it had happened. From the first day, the general wrote reassuring cables to Washington maintaining that there were only about 500 enemy troops in the city, and that despite pockets of fighting Hue remained firmly under Allied control.

Gene Roberts, the New York Times bureau chief in Saigon (and later managing editor), was the first reporter on the scene. After just one day in the encircled American compound, he knew something much bigger had happened. He could not see much of the city, but he could observe Marine units being turned back by overwhelming fire before making it a full block outside the compound. He could see the wounded and dead being carried back. He could talk to the young officers who were repeatedly ordered to attack an overwhelmingly superior, well-entrenched enemy. The contradiction between the official version and the truth was evident in the headline on his story, which ran on the front page Saturday, February 3: “ENEMY MAINTAINS TIGHT GRIP ON HUE/Force Put at Five Battalions [roughly 10,000 men] — U.S. Marines Hold Two Square Blocks of City.”

As the battleground on for nearly a month, many other reporters arrived to witness the battle firsthand, everyone from Marine combat correspondents to CBS anchorman Walter Cronkite. Most were in the thick of the fighting and wrote of the heroism, the fear, victories and the mounting losses. Several were wounded and three were later decorated by the Marines for bravery, after carrying wounded men to safety. At the same time, Westmoreland was reporting a minor clash, reporters on the scene made it clear — in words, photos, and film — that the fighting was intense and widespread — the worst of the war — often touch-and-go. Marines were battling for every house and block.

War puts reporters in a difficult spot. They may root for American success; indeed, in the field, their lives sometimes depend on it. But as journalists, they are obliged to report what they see and hear.

The battle for Hue was hard, bloody, and costly, not the minor skirmish Westmoreland was selling. Ultimately it involved 20,000 combatants on both sides, and left 10,000 or more dead. The military called it a success. Hue had been retaken, but had been mostly destroyed. But reporting about the battle had lasting effect on how Americans viewed the war. Indeed, after Tet, the debate was no longer about how to win, but how to leave.

Writing his book, Dereliction of Duty, Gen. H.R. McMaster, now Trump’s National Security Advisor, placed the blame for the war’s loss squarely on the generals. He concluded, “The failings were many and reinforcing; arrogance, weakness, lying in the pursuit of self-interest, and, above all, the abdication of responsibility to the American people.”

In one sense only, the claim that journalists were to blame is warranted. They told the truth, and the truth changed peoples’ minds. In a democracy, that’s the way it’s supposed to work.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- What Student Photojournalists Saw at the Campus Protests

- How Far Trump Would Go

- Why Maternity Care Is Underpaid

- Saving Seconds Is Better Than Hours

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Ryan Gosling

- Scientists Are Finding Out Just How Toxic Your Stuff Is

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com