If you take a train about 18 miles north of Hong Kong’s city center, and then pay the fare (a tick under a dollar) to board a creaky minibus, you will eventually find yourself on the outskirts of the village of Muk Wu, which is comfortably lost to time. Here, the dense, dated brutalist heights of Hong Kong’s apartment complexes give way to rolling hills and rice paddies. There is an old temple at the village center with incense burning inside, its outer walls swallowed by vines browned in the summer heat. Street dogs sleep at the foot of its alleys, too hot to bother growling at the occasional visitor. Because this is Hong Kong, one of the world’s most meticulously run towns, there is a public restroom along the main lane, and it is spotless.

The vision is that of Asian pastoral, but it is betrayed by the tall iron fence running along the town’s northern edge. This marks Hong Kong’s border with mainland China. On the other side is Shenzhen: a former fishing village of 30,000 that in four decades has become one of the fastest-growing and most vital cities in the world, with a population of 12 million and more skyscrapers constructed in 2016 — including the fourth-tallest building on the planet — than in all of the U.S. and Australia combined.

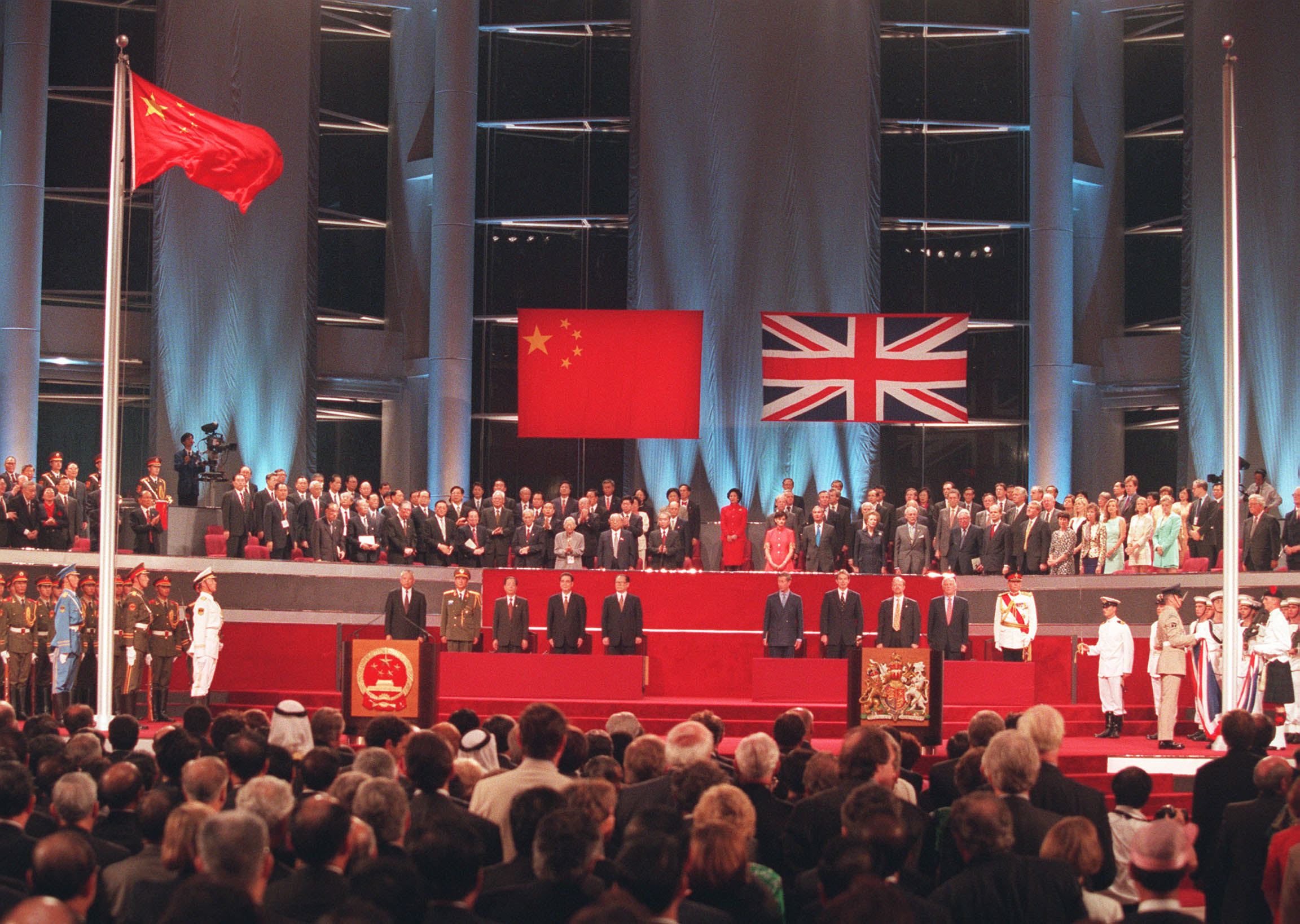

Not far from here, just before midnight on June 30, 1997, thousands of mainland Chinese troops rumbled across the border into Hong Kong. It was 156 years ago that the British wrested the territory from China amid the greed of the Opium Wars. In that time, the subtropical territory was transformed, most implausibly, and quite simply, into one of the world’s greatest metropolises. Now it was returning to Beijing’s rule under an agreement known as “one country, two systems”: Hong Kong would retain its own government and laws to bulwark its liberal capitalist ethos under the ultimate sovereignty of a communist power. Some Hong Kongers were so skeptical that they left Hong Kong for places like Canada and Australia in the years leading up to the “handover,” as it was called; others proudly waved the red Chinese flag as the troops rolled onto Hong Kong’s streets.

Twenty years have passed. Such anniversaries are arbitrary markers, mostly, but they invite an opportunity for reflection — on where things are, on pledges kept or not, on what’s to come next — and never before in Hong Kong’s history has such reflection been timelier. The story of contemporary Hong Kong, many people here will tell you, is a story of broken promises: the story of a city constitutionally bequeathed with “a high degree of autonomy,” but which has seen its crusades for democracy repeatedly defeated and its liberal values inexorably eroded by its overlords in Beijing. This as the mainland itself has flourished — China is the world’s second-biggest economy after the U.S., and its middle class ranks among the most upwardly mobile anywhere — while Hong Kong suffers from unaffordable housing, limited professional opportunities and among the widest wealth gaps in the developed world. In 1997 Hong Kong constituted almost a fifth of China’s GDP; now it’s about 3%.

Today, Hong Kong is politically and economically an increasingly integrated part of China: successive local governments have hewed ever closer to Beijing’s line, and mainland companies are now beginning to dominate local commerce, particularly real estate, which has a ripple effect through almost all the city’s business sectors. And yet: Hong Kong is, mentally and emotionally, a city apart, more so than at any time since 1997. In a recent survey by the University of Hong Kong, nearly two-thirds of respondents identified themselves as Hong Kongers rather than Chinese. “Despite the fact that we’re all Chinese, we’ve been brought up in a different culture,” says Anson Chan, a former top Hong Kong official fighting for the city’s freedoms. “We might as well have come from a different part of the world.”

Read More: Hong Kong 20th Anniversary: Portraits from Settler Society

Says Grace Wong, an education administrator in her late 30s: “Since 1997, every Hong Kong person has been able to feel the atmosphere change. The DJs on the radio talk shows are choosing their words carefully to avoid upsetting the authorities. The Hong Kong people have always been able to speak out — now what are we doing? I do not know what is happening to this city. Is it just becoming China?”

This is not what the authorities want you to believe. In recent weeks a chorus of Hong Kong and mainland officials have loudly sung the same refrain: “one country, two systems” is working just fine; discontent is not widespread but emanates from a small group of troublemakers. The Hong Kong government has thrown itself into the preparations for an epic celebration of the handover anniversary, which will be attended by Chinese President Xi Jinping. On lampposts across the city, colorful banners carry the event’s awkwardly phrased slogan: TOGETHER, PROGRESS, OPPORTUNITY. The event planning board has hosted events around the city virtually every week this year — for example: a jewelry-designing contest for local students to “express their feelings through their design towards the 20th anniversary of Hong Kong’s reunification with the Motherland.” The firework display for the anniversary will feature simplified Chinese characters, which are used on the mainland, not the traditional script common in Hong Kong. The anniversary’s official theme song, called “Hong Kong Our Home,” extols a city that is “shining ever brighter.”

“These lyrics are so flaccid,” one online commenter wrote when the song was released this spring. “Does this ‘home’ still look like a home?”

It could be argued that this malaise — the malaise that in recent years has fueled protests, prompted new emigration, and engendered a climate of bitter resignation — is nothing more than the logical conclusion of a century-and-a-half of powerlessness. “Hong Kong has always been a colony,” says 26-year-old activist Chan Ho-tin. It’s an overcast Thursday afternoon and we’re having dong nai cha — iced milk tea, a Hong Kong staple — at a fluorescent-lit diner just west of downtown. A double-decker streetcar, chartered by the government and adorned with the flags of Hong Kong and China, with a brass band playing chipper patriotic tunes on the upper deck, rumbles past on the century-old tracks outside. “We were a colony under the British,” says Chan, “and we’re a colony under the Chinese. We’ve never had a say in our future.”

It is not an unfair point. In the early 1980s, Margaret Thatcher’s government sat down with Deng Xiaoping’s to negotiate the political future of Hong Kong, the British lease on which was set to expire in 1997. It was a tricky matter. Under the Crown, Hong Kong had evolved from a collection of barren rocks into a glittering global finance and trade hub (“Colonization done well,” Prince Charles grumbled in his travel journal after the handover); China was still in its early days of industrialization, its political and economic future anxiously uncertain. The result of these talks, reached with hardly any popular input, was proportionately fraught: a complicated arrangement called “one country, two systems,” under which Hong Kong could “enjoy a high degree of autonomy,” its social systems and “life-style” unchanged, but “foreign and defense affairs” — a conveniently broad term — would be left to the Chinese government.

“What we were doing was putting in Hong Kong panes of glass, so that if the building was vandalized, the world outside would be able to see the shards of broken glass on the floor,” says Chris Patten, 73, the last British governor of Hong Kong. “That was true about the rule of law, it was true about the judiciary, it was true about human rights legislation. We put in place the sort of laws which guaranteed continuing freedom of association, freedom of worship, freedom of speech and so on.”

Read More: Hong Kong 20th Anniversary: Chris Patten, the Last Colonial Governor, Recalls the City’s Handover

“The thrust of ‘one country, two systems’ was Beijing exercising restraint,” says Emily Lau, a former pro-democracy lawmaker. “We’re just a small city — it was incumbent on Beijing to keep its promises.” Many panicked. By some estimates, as many as a million Hong Kongers scrambled to claim residency overseas in the years leading up to the handover, in particular to Canada. (Today, Vancouver is sometimes nicknamed Hongcouver.) Collectively, the city was ambivalent on the rainy night of June 30, 1997, when the Union Jack was lowered from the city’s flagpoles and the red-and-yellow Chinese flag took its place.

What assuaged people for the first decade and a half was the promise that Hong Kong would eventually be a democratic place. The territory’s legislature and district councils were already chosen in part by popular vote; eventually, Beijing pledged, Hong Kong’s top leader, the Chief Executive (CE), would be, too. (Since 1997, the office has been filled by a 1,200-member committee seen as a conduit for Beijing’s choice of CE.)

Comforted by what would prove to a misconception, Hong Kong people happily fell into their role at the nexus of China and the world. Life was good. Unemployment barely topped 5%, even during the Great Recession. When Beijing hosted the Olympics in the summer of 2008, people here heckled the handful of protesters who came out to denounce China’s interference in Tibet. “What kind of Chinese are you?” one Hong Konger yelled at a demonstrator. Children crowded the sidewalks to wave little Chinese flags as torchbearers carried the Olympic flame through the streets.

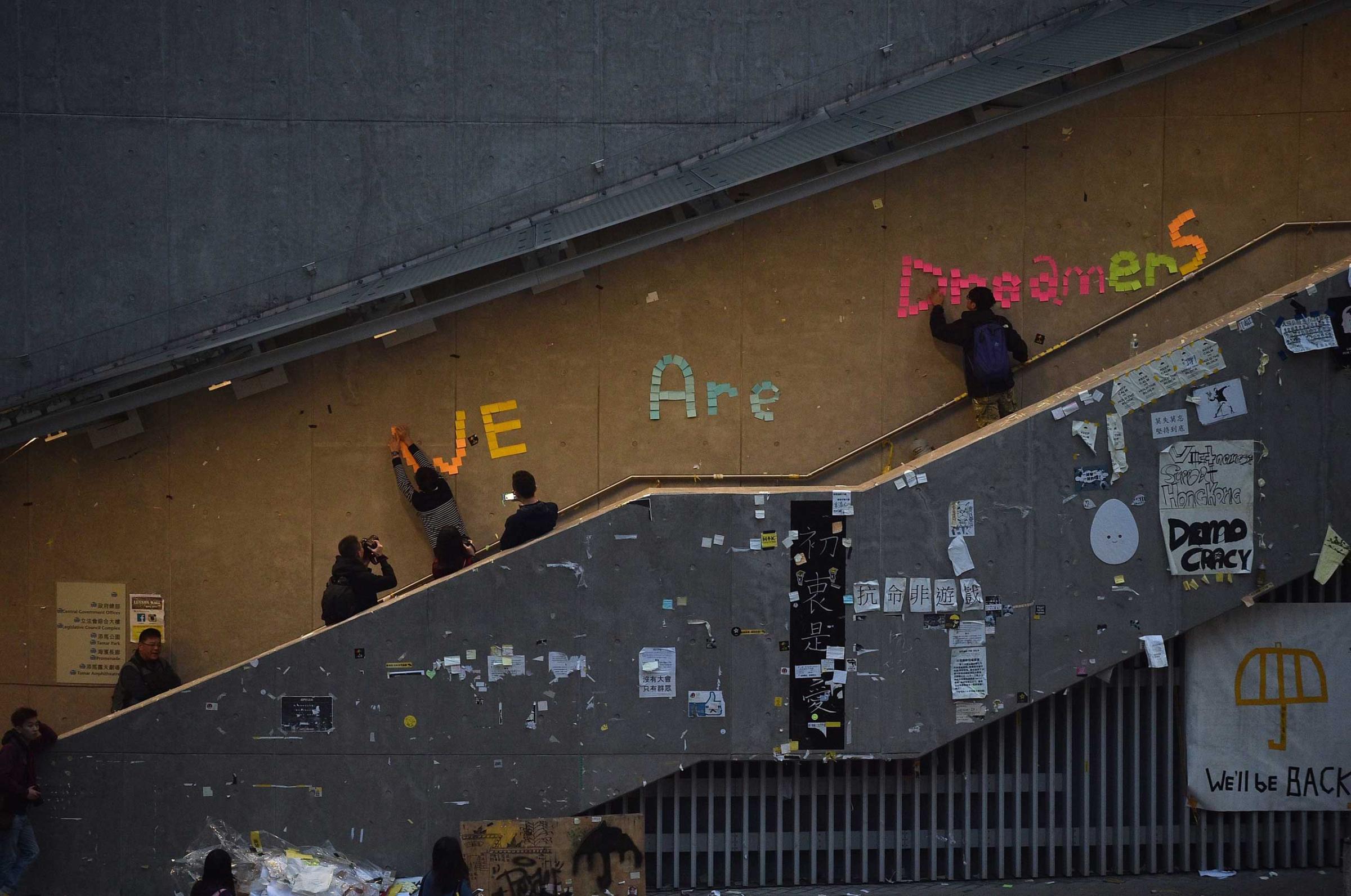

And then the children grew up. Historians looking back on the second decade of the 21st century will likely trace its liberal political upheavals to disaffected, plugged-in youth: the Arab Spring, the Bersih protests in Malaysia, the grassroots movements of Bernie Sanders and Jeremy Corbyn — and also Hong Kong, where a new, embattled generation born on the cusp of the handover was no longer swayed by the colorful optics that adorned an authoritarian state’s sovereignty over the world’s freest city. They wanted to think for themselves. They wanted to vote. “It was clear our autonomy was threatened,” says 20-year-old Joshua Wong. “‘One country, two systems’ had devolved to ‘one country, one-and-a-half systems.”

The bespectacled, angular Wong is familiar to anyone who has followed Hong Kong’s political drama in the last five years. In 2012, at the age of 15, he led a demonstration against a government campaign to create a local academic curriculum that would instill “national education” and a patriotic respect for mainland China. I first met him two summers after that, in a noodle shop tucked beneath the gritty neon lights of Wan Chai district.

Things were tense. The CE, an aloof businessman named Leung Chun-ying, was increasingly unpopular, spurring new calls for direct elections. Beijing did not seem to be listening. “To affect the world, you go to the streets,” Wong told me that night.

Read More: The Hong Kong Protests Have Given Rise to a New Political Generation

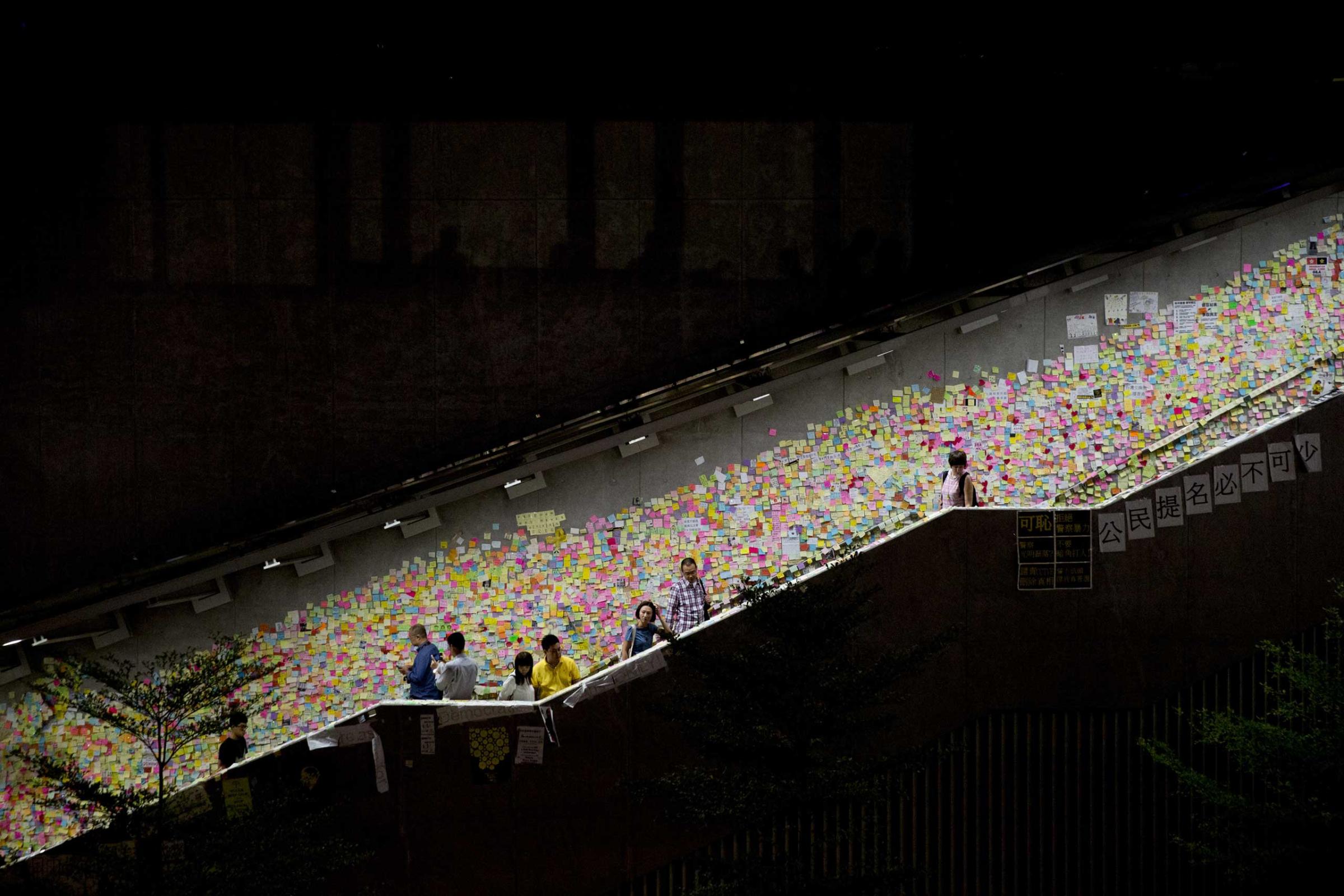

Two months later, he — and hundreds of thousands of others — did just that. After Beijing declared that the CE must be someone who “loves Hong Kong,” activists took to the streets of key commercial districts, where they remained for three months. It was a demand for suffrage, but more cosmically it was a repudiation of any illusion of sameness between Hong Kong and the mainland. It was known as the Umbrella Movement, because protesters used umbrellas to shield themselves from police tear gas; its unofficial anthem was a song by local musicians called “Raise the Umbrella.”

“Chinese nationalism went viral during the Olympics in 2008, but when I started to think about it, it was clear we were just two different cultures,” the activist Chan Ho-tin says over tea. “We speak different languages. We have different values. We value freedom. Fairness.”

Chan is the leader of the Hong Kong National Party, a political group that emerged about a year ago on the wave of an unprecedented movement: the call for Hong Kong’s outright independence from mainland China. Things had not improved in the wake of the Umbrella protests. In late 2015, five Hong Kong-based publishers who sold salacious books critical of mainland Chinese officials went missing and later turned up in the custody of

mainland police — a flagrant violation of the legal protections afforded to Hong Kong under “one country, two systems.” Last summer, one in six Hong Kongers said they supported the territory’s independence, according to a local university poll; in September, two proponents of it, Baggio Leung and Yau Wai-ching, were elected to Hong Kong’s Legislative Council. Within 10 weeks, Beijing had interfered to decree they were not allowed to take office.

79 Days That Shook Hong Kong

“It was a wakeup call for China — it wasn’t just a few idealists advocating something unserious,” says Michael Tien, a tycoon and pro-Beijing legislator. “And it had to do with various departments in China not treating us sensitively — not respecting our concept of freedom of speech, our passionate dedication to the law. It gave the activists ammunition.”

Even its defenders admit that independence is impractical. (“Not in this generation, at least,” says Chan Ho-tin.) For all of Hong Kong’s disdain for the mainland — go to YouTube and search “Hong Konger yells at rude mainlander for eating on subway” — the cruel irony is that Hong Kong needs mainland China more than mainland China needs Hong Kong: for electricity and water, for food imports, and most critically for the economic capital that has sustained Hong Kong’s financial institutions and tourist industry as the mainland’s economy has boomed. Once hailed as Asia’s “World City,” Hong Kong’s GDP now lags behind that of Shanghai and Beijing; recently it was reported that Hong Kong will be overtaken by the southern China city of Guangzhou as the dominant regional air travel hub within a couple of years. The mainland is on the cutting edge of smartphone app development and boasts a film industry set to surpass Hollywood. Hong Kong has exactly zero art museums of global renown and a failed government-developed tech campus called Cyberport, whose most exciting tenants after 11 years are the Hong Kong Free Press, an online news site launched in 2015 in response to the perceived crackdown on local media, and a movie theater.

Read More: 8 Questions for Hong Kong Democracy Activist Joshua Wong

Politically conscious young people are well aware of these issues, and blame them on a local government that they say has prioritized pleasing Beijing over fixing the city. They are unlikely to change their minds about this. In March, the committee to choose the next CE picked Carrie Lam, a 60-year-old career bureaucrat who has increasingly expressed pro-Beijing sentiments. During a recent interview with CNN, Lam said about the kidnappings of Hong Kong residents: “It would not be appropriate for us to challenge what happens on the mainland.”

Angered by continual anti-Beijing protests in Hong Kong, and by the emergence of an independence movement, however nominal, China’s leaders are reading the city the riot act. “The relationship between the central government and Hong Kong is that of delegation of power, not power-sharing.” Zhang Dejiang, chairman of China’s National People’s Congress, said recently. While Lam says she and her team will focus on livelihood issues, it’s likely Beijing will pressure her to introduce national education as well as national security laws similar to those on the mainland.

Is Hong Kong as it was, and still is, doomed? Over the decades, the city has always been able to bounce back from adversity. Chris Patten believes Hong Kong will survive its latest challenges too. “It’s wonderful that young and old people in Hong Kong have such a strong sense of what it means to be a citizen in a plural society,” says Patten. “It remains a terrific city, one of the freest cities in Asia. That is not because of Beijing; it’s not because of Britain. It’s because of the people of Hong Kong.”

— With reporting by Kevin Lui / Hong Kong

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com