An active shooter recently attempted to assassinate Republican members of Congress at an early morning baseball practice in the suburbs of Washington, D.C. Days earlier, a man spewing anti-Muslim hate speech fatally stabbed two individuals on public transport in Portland, Oregon. The month before, protesters came to fisticuffs at dueling political rallies in Berkeley, California.

Events such as these add to the growing sense that something has broken in our politics. Something that once moderated our partisan feelings and bridled our baser instincts has gone missing in an era of unprecedented polarization. Something fundamental to our civic culture has been lost amid the chaos and disruption of the Information Age.

The question is, What has been lost?

In a word: civility.

Civility is the indispensable political norm. It is the public virtue that has greased the wheels of our democracy since its inception. Although nowhere mandated in our Constitution, civility is no less essential to the proper functioning of our government than any amendment, court ruling or act of Congress. Without it, little separates us from the cruelty and chaos of rule by force.

For decades, civility has acted as the levee protecting our society from its own worst impulses. But that levee now shows signs of strain as political passions spill over into open violence.

In the wake of the attack on members of Congress, I have reflected at length on the circumstances that led us to this point. While it may be difficult to trace the erosion of civility to any single factor, one thing is certain: Our nation cannot continue on its current path. Either we remain passive observers to the problem, or we endeavor to act, to make the necessary changes — in ourselves, in our families and in our communities — that will lead to a more civil, prosperous society.

Restoring civility to the public square won’t happen overnight — but it must happen.

The first step is to speak responsibly.

Our words have consequences, and in an age of retweets, viral videos and shareable content, those words often echo well beyond their intended audience and context. It’s incumbent on all of us, then — from the President to Congress on down — to be responsible for our speech.

I will be the first to admit to saying things over the course of my public service that I later came to regret. In the heat of an argument, it’s easy to indulge in irresponsible rhetoric. But we must avoid this temptation. Whether in town halls, casual conversations with neighbors or posts on social media, we must likewise refrain from dehumanizing, demeaning or unfairly disparaging the other side. And we must resist the impulse to frame every tiny policy disagreement as a zero-sum struggle for the soul of the country. We must restore sense, decency and proportion to our political speech.

The second step is practicing media mindfulness.

Just as the food we eat affects the body, the information we consume affects the mind. The daily consumption of media that presents only one political viewpoint — whether conservative or liberal — cocoons the mind in a safely sealed ideological echo chamber. An imbalanced media diet shrinks our perception of reality, which in turn limits our capacity for empathy and our ability to engage civilly with others.

To better understand how the other side thinks and feels, we must make a conscious effort to diversify our media intake. This exercise in empathy may not heal decades-old political divisions or usher in a post-partisan age. But it will at least help us break free from party groupthink and be better prepared to engage in civil debate with friends and neighbors.

The next step toward civility is to venture beyond the comfortable confines of our social circles.

Americans today are much less likely to marry, date or even live near people of the opposing party. Increasingly, we sort ourselves by ideology and lifestyle — a phenomenon that only increases polarization over time.

How can we expect to engage politically with members of the opposing party if we don’t even interact socially with one another? Like limiting our media consumption, only associating with those who hold our same values and opinions distorts our perception of the other side. It has an “othering” effect so severe that Republicans and Democrats — freedom-loving men and women who share the same country and many of the same values — increasingly see each other as enemies.

In the spirit of civility, we would all do well to make friends with members of the opposing party. I speak from personal experience.

When I first came to Washington, the culture of Congress was vastly different than it is today. There was a level of respect and congeniality among colleagues that was hard to find anywhere else. Some of my best friends were Democrats. One moment, we would be yelling at each other on the Senate floor; the next, we would be laughing together over family dinner. In those days, Republicans and Democrats locked horns often, but we also loved each other.

I worry that those special relationships have been lost today. In 2017, Republican and Democratic Members of Congress seldom socialize outside of votes and committee hearings. We used to break bread together; our spouses used to plan weekend trips; our children used to attend the same schools. But today, our families barely know each other — if they know each other at all. In the weekly race to return to our home states as soon as possible, we miss out on opportunities to share with one another the more intimate, humanizing parts of our lives. As a result, something vital has been lost. We now struggle to see the common humanity in the other side, and we increasingly treat each other as opponents rather than friends.

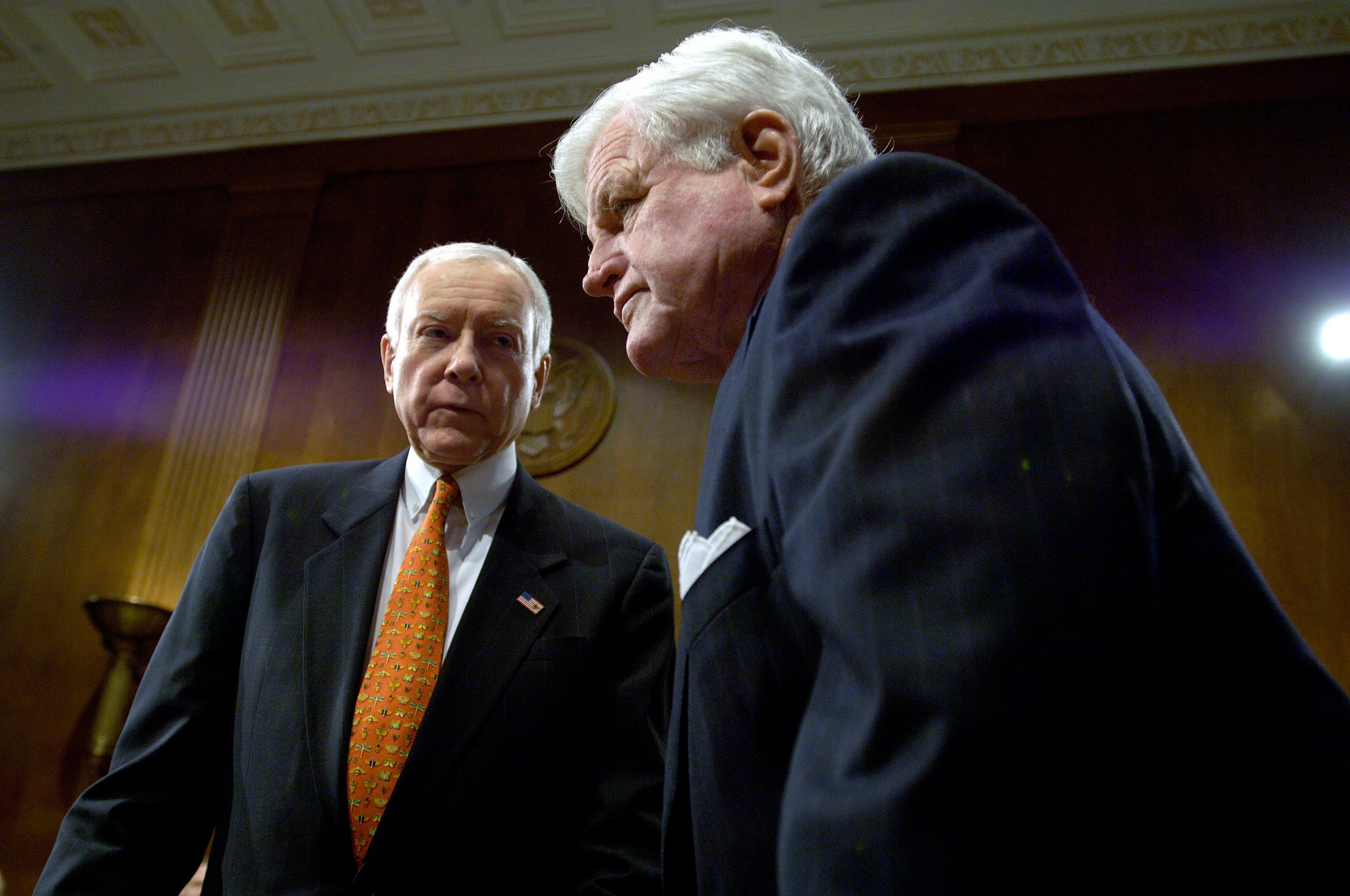

I’m grateful for the late Senator Ted Kennedy, who taught me that the bonds of friendship are stronger than any partisan pull. When I first joined the Senate, I thought Teddy would be an adversary. Instead, we became the best of friends.

Teddy and I were a case study in contradictions. He was born into privilege; I was brought up in poverty. He was an East Coast liberal; I was a Reagan conservative. He was a Catholic; I was a Mormon. Yet time and again, we were able to look past our differences to find areas of agreement and forge consensus. Had Teddy and I chosen party loyalty over friendship, we would not have passed some of the most significant bipartisan achievements of modern times — from the Americans with Disabilities Act and the Religious Freedom Restoration Act to the Ryan White bill and the State Children’s Health Insurance Program.

My unlikely friendship with Ted Kennedy is but a small example of what our nation can accomplish if we choose respect and comity over anger and discord. Only by doing so can we look beyond the horizon of our differences to find common ground.

Today, I want to make a personal commitment to exercise greater civility in my day-to-day interactions with fellow Americans; I hope you will join me in doing the same.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Canada Fell Out of Love With Trudeau

- Trump Is Treating the Globe Like a Monopoly Board

- Bad Bunny On Heartbreak and New Album

- See Photos of Devastating Palisades Fire in California

- 10 Boundaries Therapists Want You to Set in the New Year

- The Motivational Trick That Makes You Exercise Harder

- Nicole Kidman Is a Pure Pleasure to Watch in Babygirl

- Column: Jimmy Carter’s Global Legacy Was Moral Clarity

Contact us at letters@time.com