In the United States, the Fourth of July holiday commemorates the day in 1776 when the Continental Congress approved the Declaration of Independence. What it doesn’t commemorate is an actual step that made the U.S. a brand new, independent nation.

According to Philip Mead, chief historian at the Museum of the American Revolution, the legendary declaration was essentially a “press release” explaining to the world why the delegates had voted to break free from the British Empire — a decision they’d made two days earlier. And July 2 isn’t even the only date that could lay a claim to being the real beginning of American nationhood.

Here, TIME looks back at what happened on that day and four other dates on the road to American independence:

May 15, 1776: The fifth Virginia Convention sends the Continental Congress instructions for the colonies to unite and declare independence

All of the other colonies were on board once that key step was taken by Virginia — “the largest, wealthiest, most populous colony,” explained Joseph Beatty, Colonial Williamsburg’s Director of Research & Interpretation. To mark the occasion, the British flag was lowered over the Capitol building in Williamsburg and replaced with the Grand Union flag, considered the first American flag. A party with cannon fire and fireworks followed.

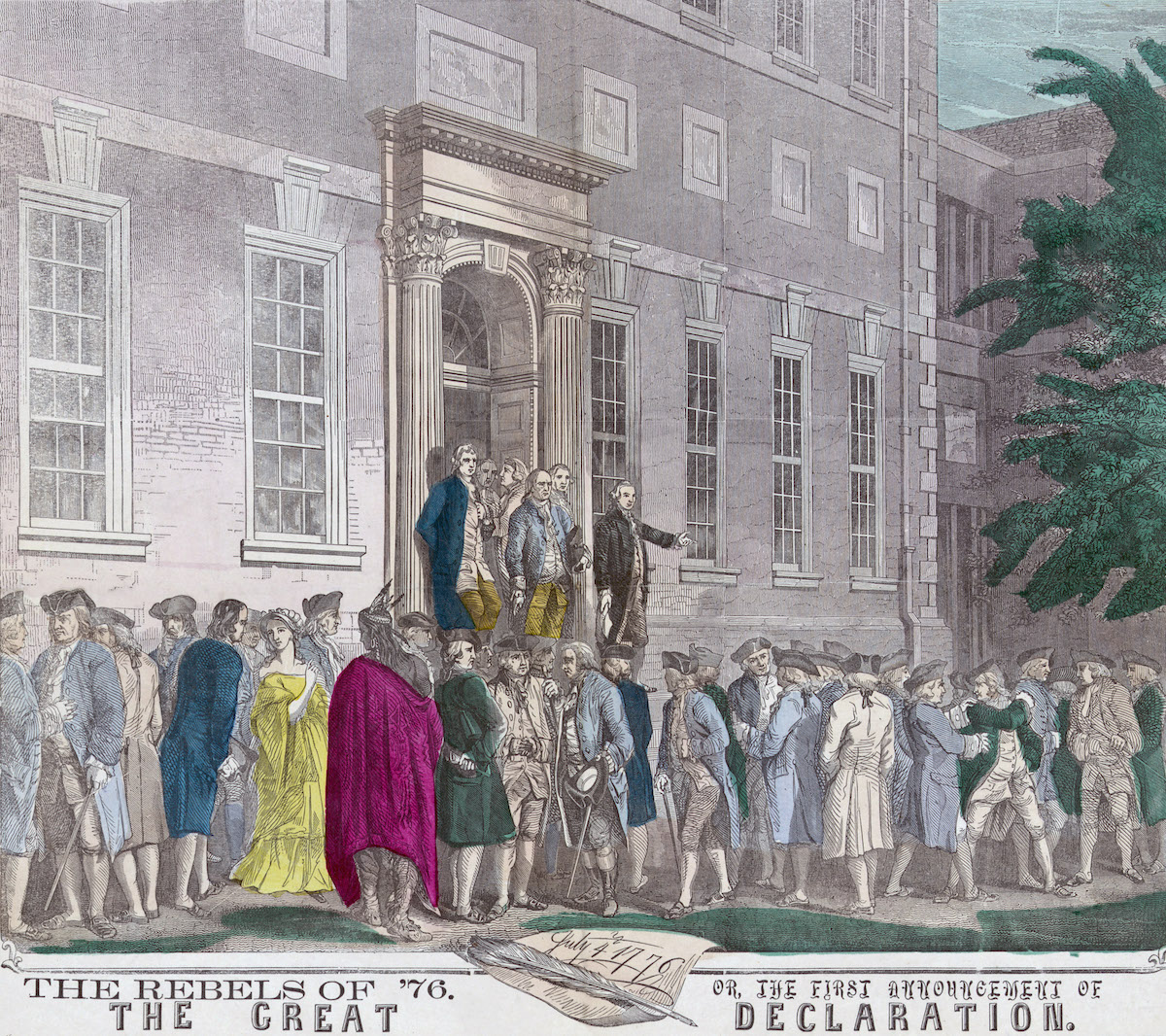

July 2, 1776: The U.S. votes for independence from Britain

The Second Continental Congress voted in favor of Richard Henry Lee’s resolution declaring such. The next day, future President John Adams wrote to his wife Abigail predicting that the Second of July “would be “celebrated, by succeeding Generations, as the great anniversary Festival” with “pomp and parade, games, sports, guns, bells, bonfires, and illuminations from one end of this continent to the other.” (Why was John Adams wrong? A big part of the equation was that “July 4, 1776” appears at the top of the Declaration of Independence, since it was delivered to the printer that day, according to Joseph J. Ellis, author of Founding Brothers: The Revolutionary Generation.)

Sept. 3, 1783: King George III signs the Treaty of Paris

The British king’s signing of the treaty officially ended the Revolutionary War and “formally recognized the United States as an independent nation,” according to the Library of Congress. It also provided guidelines for American westward expansion (which would later be disputed).

Sept. 17, 1787: Delegates sign the U.S. Constitution in Philadelphia

The Constitutional Convention met to approve the final draft of a document that replaced the Articles of Confederation, thus strengthening the power of a federal government and creating three branches of government that provide checks and balances on one another. As Carol Berkin, a historian of early American at the City University of New York puts it, “establishing the Constitution is as important, maybe more important, than declaring independence — after all, declaring it was not the same as achieving it!”

June 21, 1788: The U.S. Constitution is ratified

New Hampshire was the ninth state to agree to the new form of government. At that point, “the Constitution became the official governing document of the United States,” as the National Constitution Center puts it, for “it was agreed that the document would not be binding until its ratification by nine of the 13 existing states.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Biden Dropped Out

- Ukraine’s Plan to Survive Trump

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com