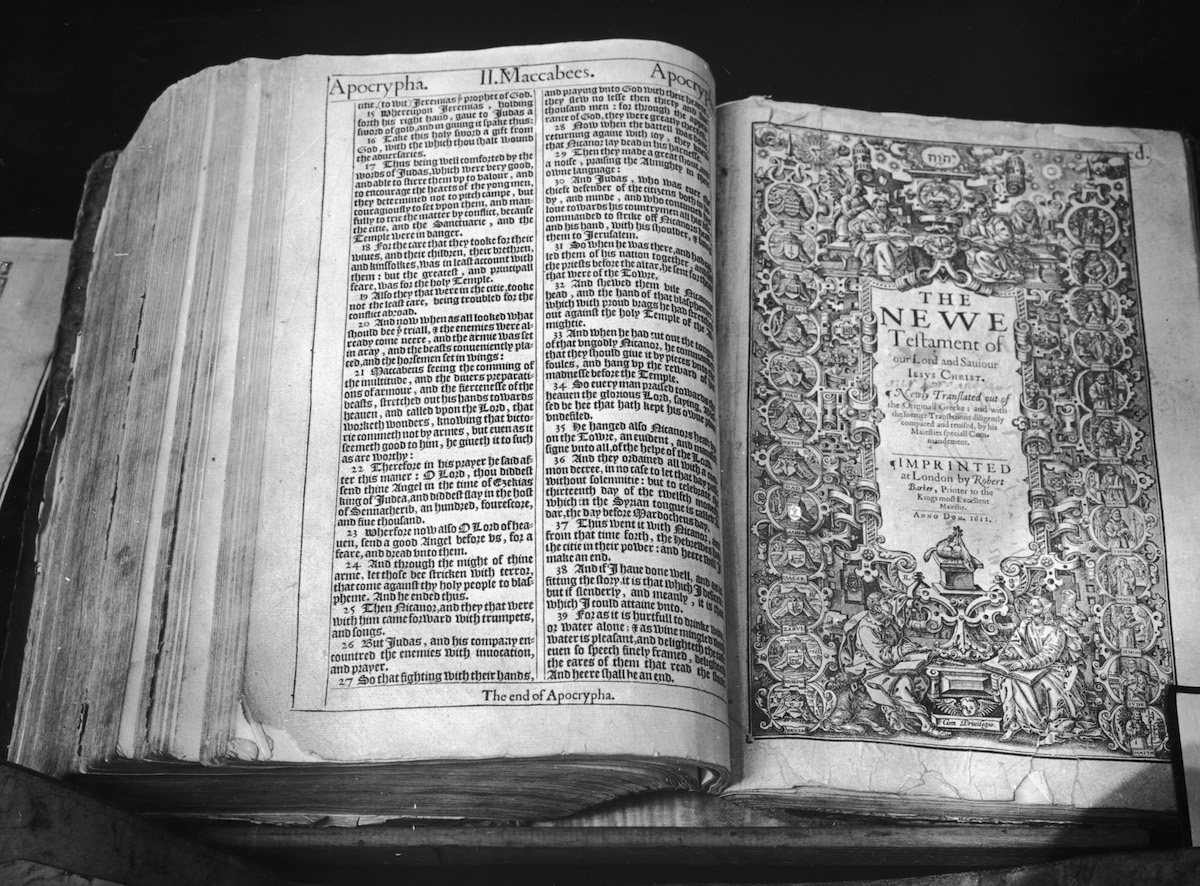

Precisely 451 years after the June 19, 1566, birth of King James I of England, one achievement of his reign still stands above the rest: the 1611 English translation of the Old and New Testaments that bears his name. The King James Bible, one of the most printed books ever, transformed the English language, coining everyday phrases like “the root of all evil.”

But what motivated James to authorize the project?

He inherited a contentious religious situation. Just about 50 years before he came to power, Queen Elizabeth I’s half-sister, Queen Mary I (“Bloody Mary”), a Catholic, had executed nearly 250 Protestants during her short reign. Elizabeth, as Queen, affirmed the legitimacy of her father Henry VIII’s Anglican Church, but maintained a settlement by which Protestants and Puritans were allowed to practice their own varieties of the religion. The Anglican Church was thus under attack from Puritans and Calvinists seeking to do away with bishops and their hierarchy. Eventually, in the 1640s, these bitter disputes would become catalysts of the English Civil War. But during James’ reign, they were expressed in a very different forum: translation.

Translations of ancient texts exploded in the 15th century. Scholars in Italy, Holland and elsewhere perfected the Latin of Cicero and learned Greek and Hebrew. The “rediscovery” of these languages and the advent of printing allowed access to knowledge not only secular (the pagan Classics) but also sacred (the Bible in its original languages). The new market for translated texts created an urgent demand for individuals capable of reading the ancient languages. Its fulfillment was nowhere better seen than in the foundation at Oxford University in 1517, by one of Henry VIII’s personal advisors, of Corpus Christi College — the first Renaissance institution in Oxford, whose trilingual holdings of manuscripts in Latin, Greek and Hebrew Erasmus himself celebrated. At the same time, Protestant scholars used their new learning to render the Bible into common tongues, meant to give people a more direct relationship with God. The result, in England, was the publication of translations starting with William Tyndale’s 1526 Bible and culminating in the so-called “Geneva Bible” completed by Calvinists whom Queen Mary had exiled to Switzerland.

This was the Bible most popular among reformers at the time of James’ accession. But its circulation threatened the Anglican bishops. Not only did the Geneva Bible supplant their translation (the co-called Bishops’ Bible), but it also appeared to challenge the primacy of secular rulers and the bishops’ authority. One of its scathing annotations compared the locusts of the Apocalypse to swarming hordes of “Prelates” dominating the Church. Others referred to the apostles and Christ himself as “holy fools,” an approving phrase meant to evoke their disdain for “all outward pompe” in contrast to the supposed decadence of the Anglican and Catholic Churches.

In 1604, King James, himself a religious scholar who had re-translated some of the psalms, sought to unite these factions — and his people — through one universally accepted text. The idea was proposed at a conference of scholars at Hampton Court by a Puritan, John Rainolds, the seventh President of Corpus Christi College. Rainolds hoped that James would turn his face against the Bishops’ Bible, but his plan backfired when the King insisted that the new translation be based on it and condemned the “partial, untrue, seditious” notes of the Geneva translation.

Though disappointed, Rainolds pressed on and was charged with producing a translation of the Prophets. He set about his work with a committee in his rooms, still in daily use today, in Corpus Christi College, as five similar committees elsewhere rendered different books of the Bible. These scholars examined every word to determine the most felicitous turns of phrase before sending their work to colleagues for confirmation. The process, which one historian called a progenitor to modern “peer-review,” lasted seven years. Rainolds, dying in 1607, never saw the publication of his great work four years later.

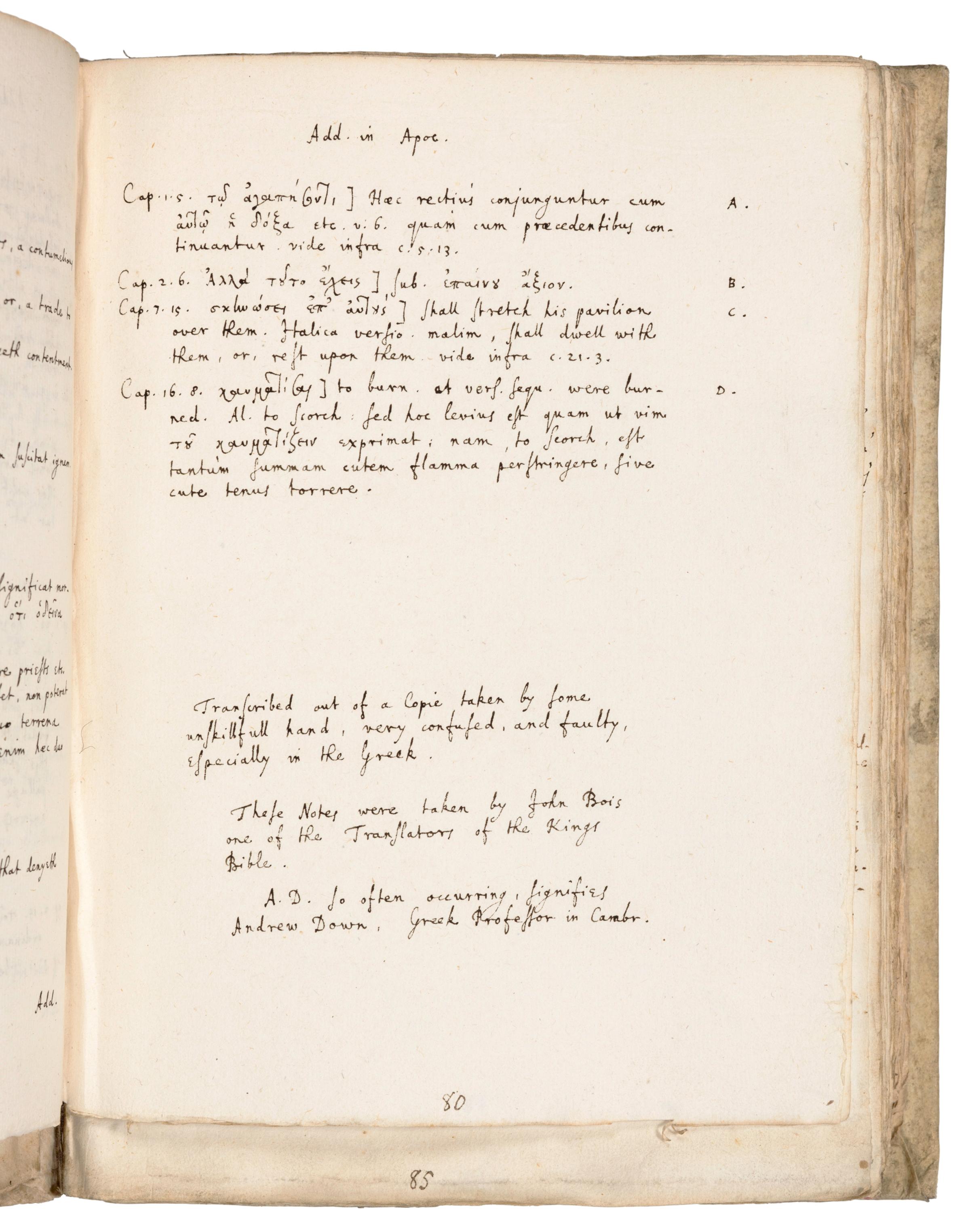

Organized to celebrate the quincentenary of Corpus Christi College (a secular institution in spite of its name), the new exhibition “500 Years of Treasures from Oxford” — now at Yeshiva University Museum at Manhattan’s Center for Jewish History — includes several Hebrew manuscripts almost certainly consulted by Rainolds and his colleagues, including one of the oldest commentaries by the great medieval rabbinical scholar, Rashi. A set of the translators’ own notes — one of only three surviving copies (seen above at left) — is also included. This precious text shows Greek, Latin and English lines, revealing the detailed craft behind the King James Bible — a testament not only to the tireless endeavor of John Rainolds, but to the importance of learning in one of humanity’s most prized religious works.

Joel J. Levy is President and Chief Executive Officer of the Center for Jewish History. Learn more about the 500 Years of Treasures from Oxford exhibit here.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com