Coal and the people who mine it have exploded onto the public consciousness since the election of President Donald Trump last fall. Trump promised to end what he described as an Obama-era “war on coal.” On the campaign trail and on Thursday he said that the rough conditions coal miners face would be turned around by a new era of American “energy dominance.”

“You’ve gone through eight years of hell,” Trump said. But “we have finally ended the war on coal.”

But, despite the rhetoric, suffering in coal country is not a new phenomenon.

Coal production has generally ramped up steadily since the conclusion of World War II, with an occasional downturn. But during the same time period the number of people employed by the industry has declined dramatically, as machines have replaced humans and engineers have invented more efficient ways to mine coal.

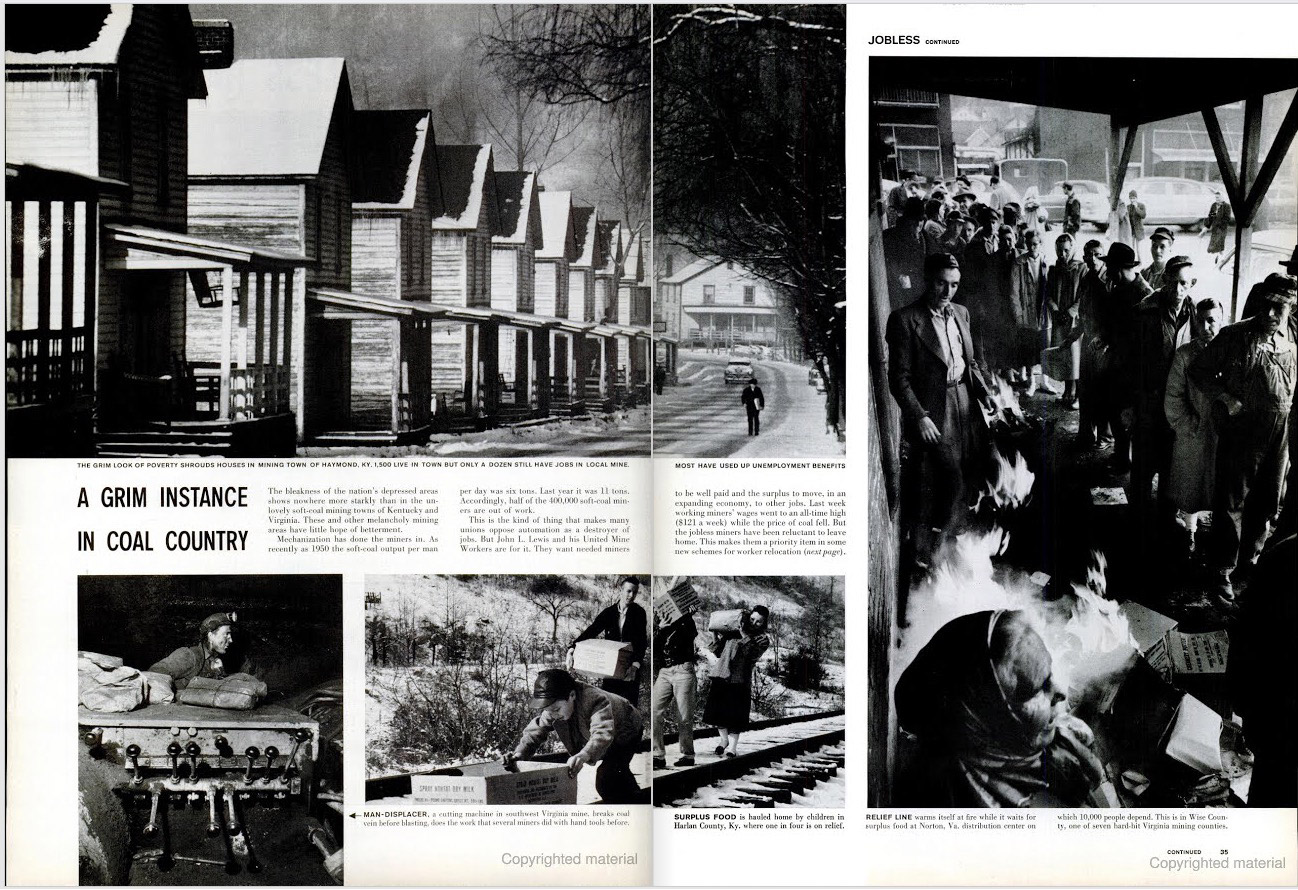

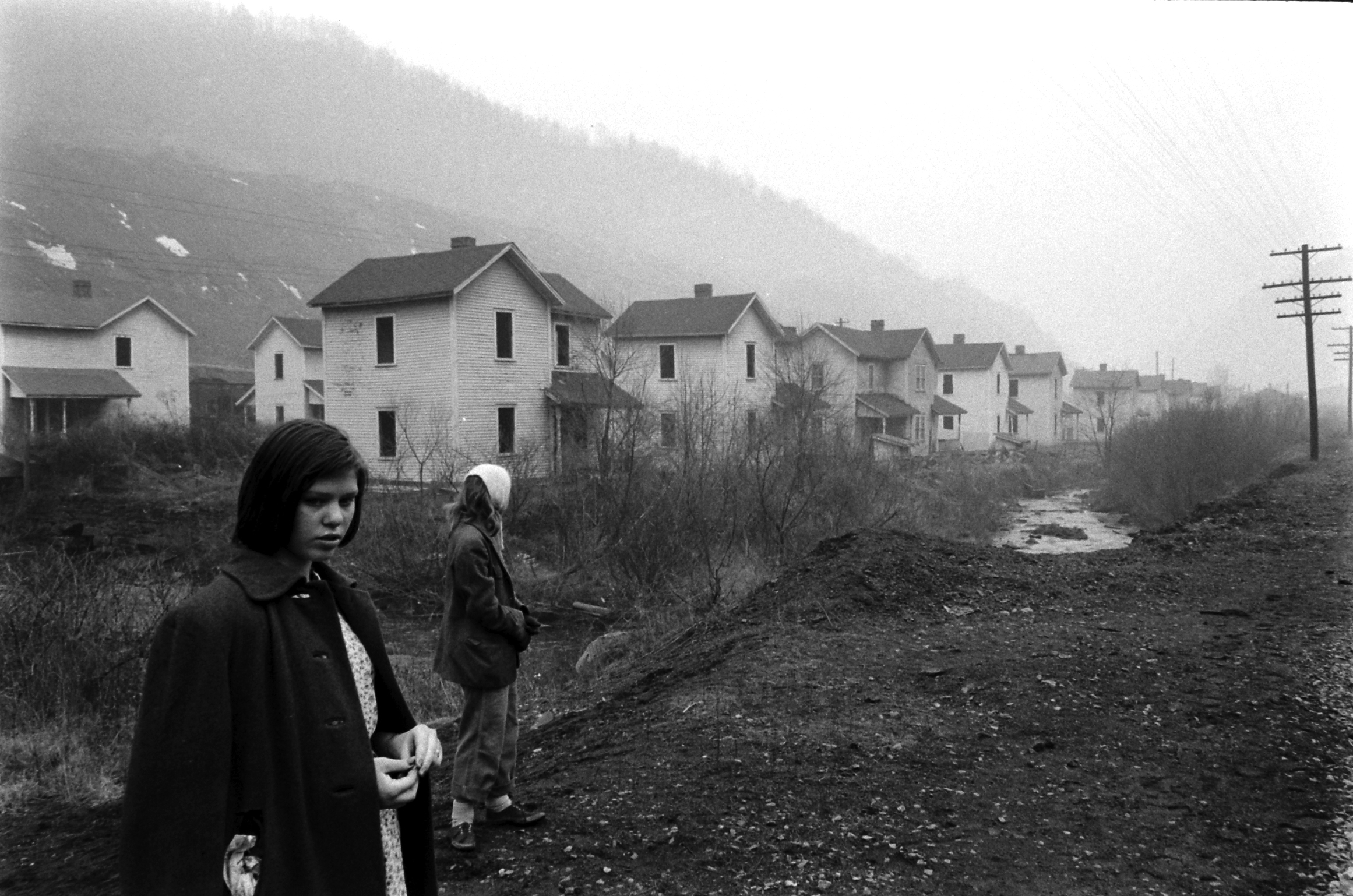

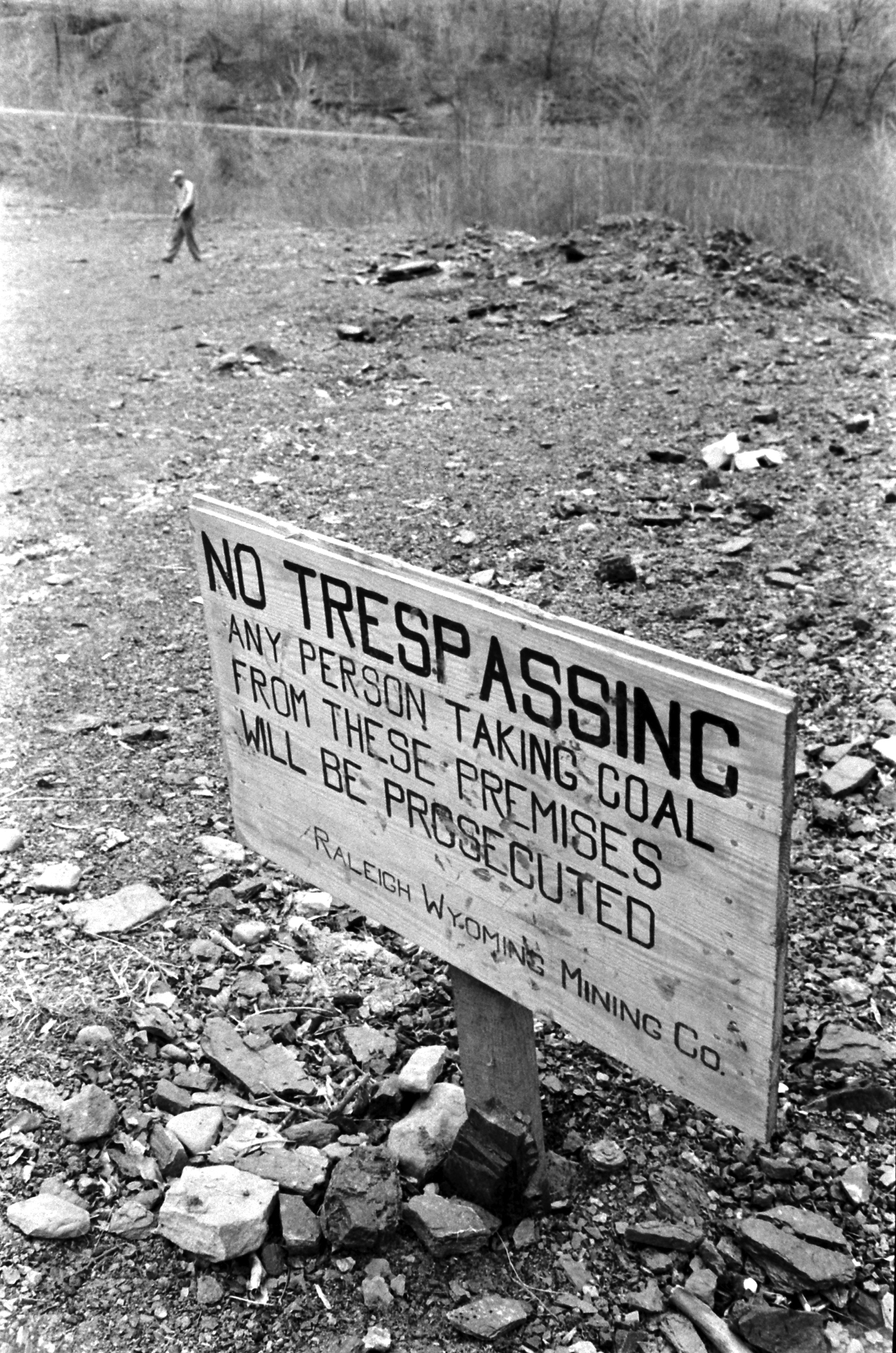

Images published in LIFE Magazine in 1959 captured what to date remains the most precipitous sustained downturn for coal mining employment: the period between World War II and the early 1960s. During that time the number of coal employees fell from nearly 400,000 to less than 150,000 following the widespread adoption of new job-killing technology. Notes from the LIFE archive describe the coal loader — the most significant development leading to a decline in jobs at the time — as having “mechanical arms” that “resemble the action of the claws of a giant crab.” The machine could load 225 tons of coal in one hour, according to the notes.

“You have an industry that’s very, very productive,” says William Gorby, a researcher at West Virginia University who studies Appalachian History, of mechanization. “But it’s not employing that many people.”

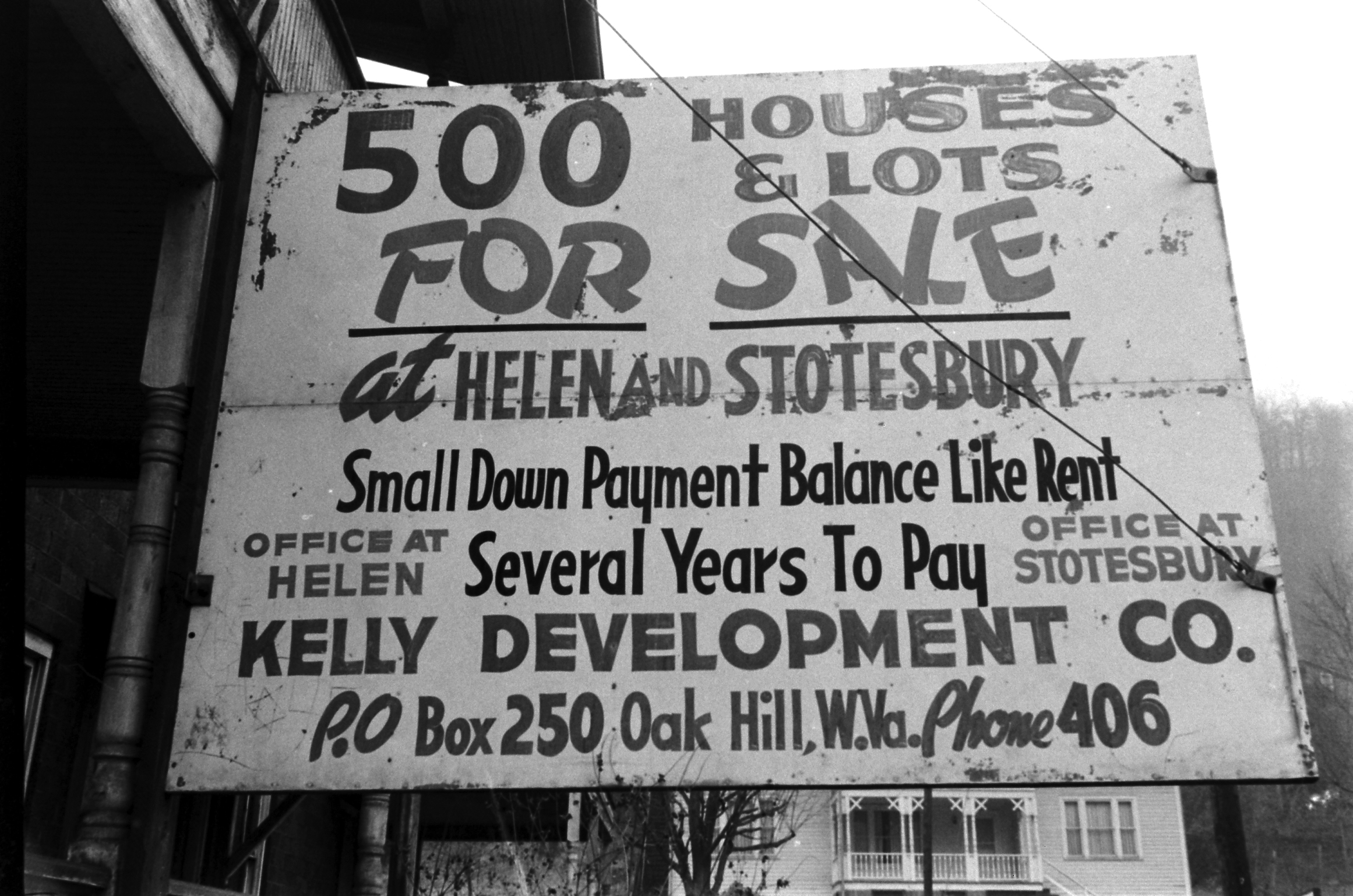

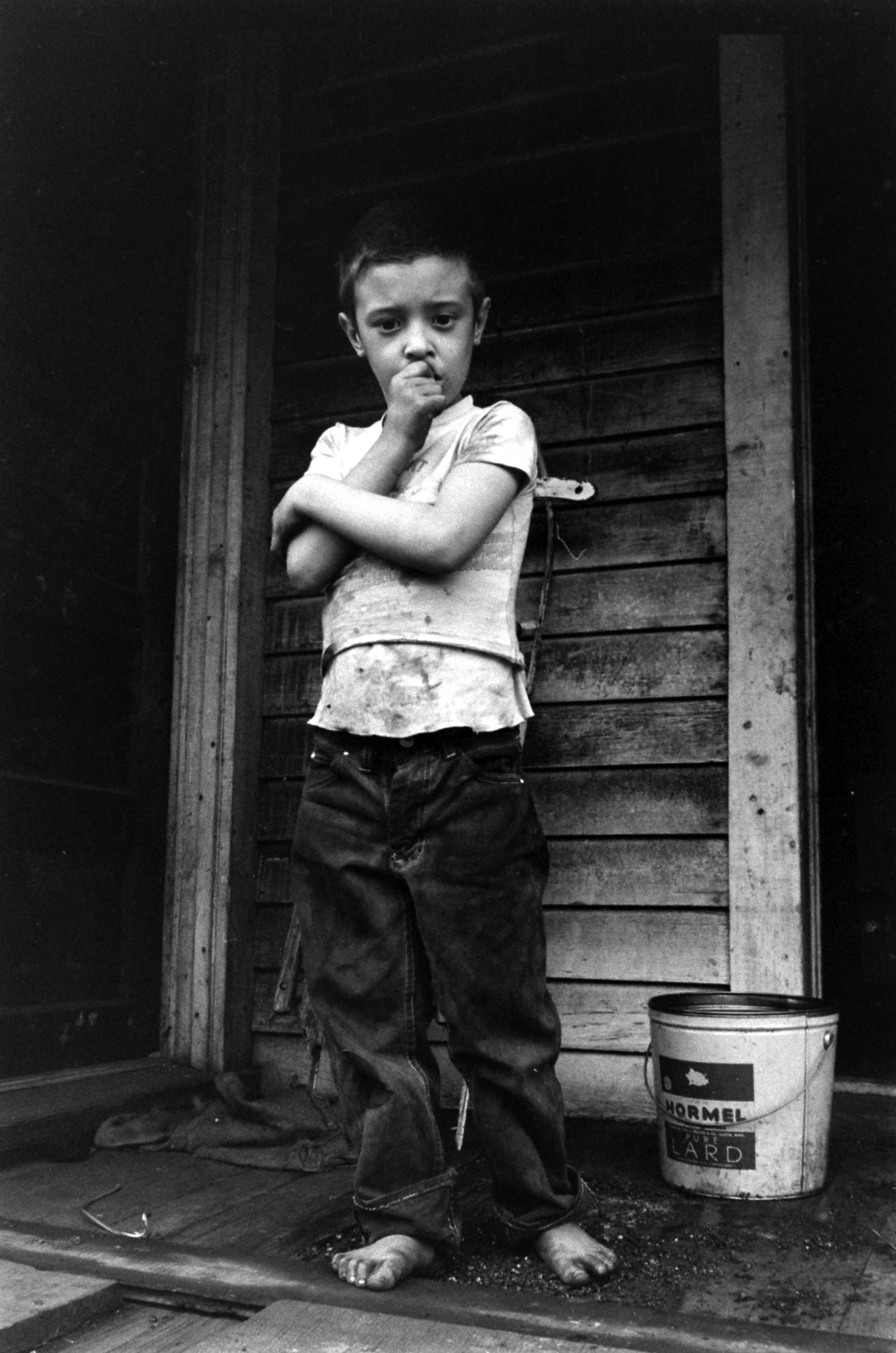

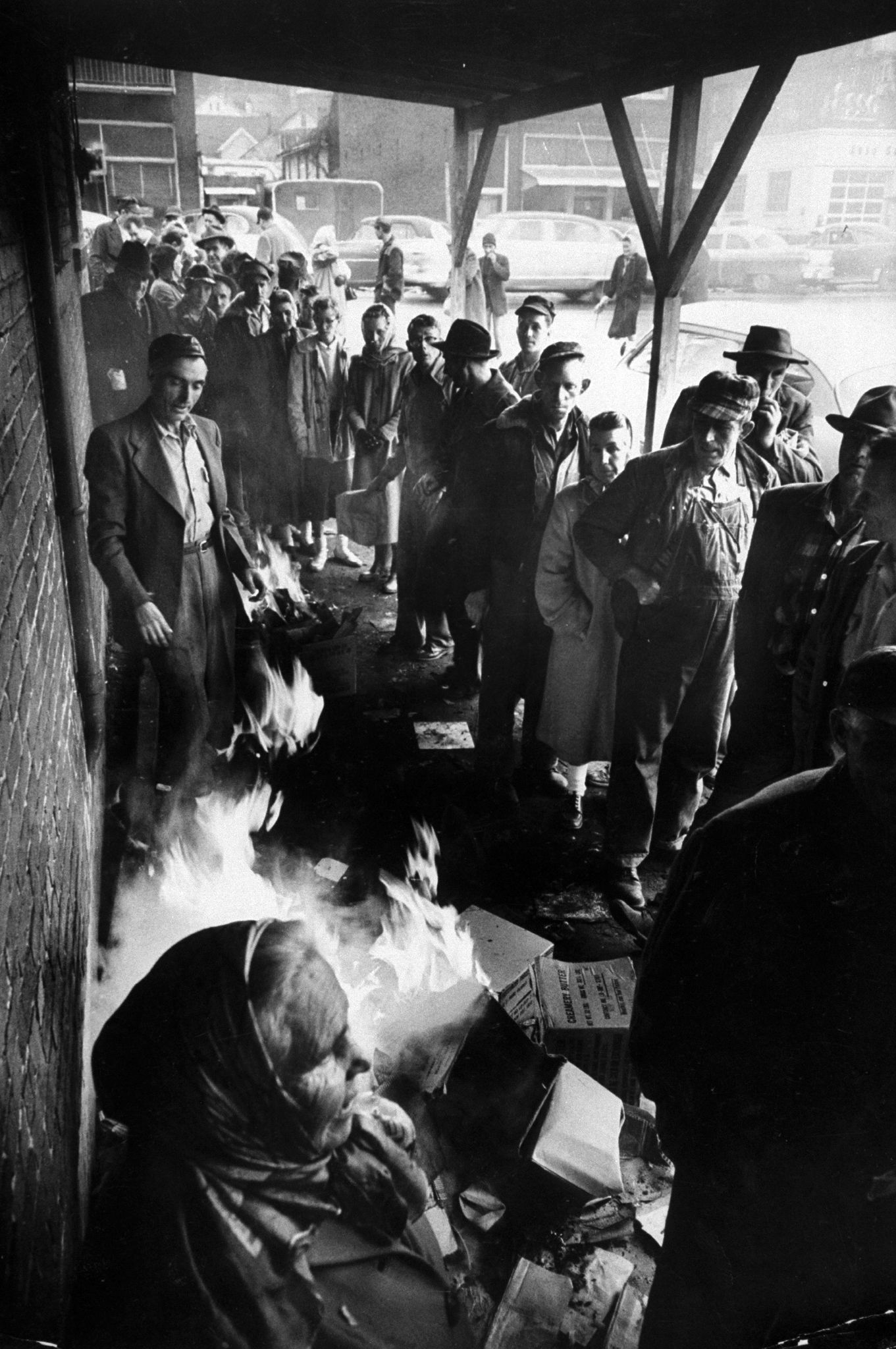

As LIFE highlighted at the time, programs did exist to help mine workers relocate from economically depressed regions, but they were often greeted by workers with reluctance — even though a tough life awaited those who stayed. In Beckley, W.V., a fifth of the county, or 10,000 people, received surplus food from a single distribution center, according to notes from the LIFE archive. Children often went to school malnourished.

The coal industry continued to improve in productivity in the following decades as mechanization continued and mine companies began a practice called surface mining, which is more efficient and requires fewer employees.

That reality— having been joined by a slew of other pressures, most significantly competition from cheap natural gas — continues to this day.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

Write to Justin Worland at justin.worland@time.com