On most Saturday mornings, my brother Billy and I would wake to my dad’s voice: “GET IN THE CAH.”

It was Darth Vader with a Boston Accent. The tone, the breathing, the dramatic pause, followed by the sudden sweeping exit. My dad didn’t need the helmet and cape, he had the attitude. He was six feet tall, average height, but seemed like a giant to us. He had the same weathered Irish American looks that most other dads in Norwood, Massachusetts, had, but he had an extra, brooding intensity. The kind that comes in handy when you’re Leading a Galactic Empire through fear and intimidation, or trying to get two young boys to wake up early on a weekend morning and get in the car.

Billy and I would immediately scramble downstairs and get into the backseat of Dad’s Dodge Dart. My dad would drive in silence, always leaving us to wonder where we might be going. We were never told, and we knew better than to ask. We wondered, Would it be to the site of the Boston Massacre? A walk on the deck of Old Ironsides? A climb up the steeple of the Old North Church? Perhaps a stroll along the Freedom Trail?

Clearly, our excursions tended to involve the Revolutionary War, but it wasn’t because my dad was some kind of colonial buff. We lived in New England in 1976, and everyone was stricken with Bicentennial fever. It seemed that we had been celebrating this event for my whole childhood, actually: every town was preparing for its own Bicentennial celebration, and in school we would perform Bicentennial plays, sing Bicentennial songs, and paint Bicentennial dinner plates. On those Saturday trips with Dad, Billy and I always enjoyed whatever historical exhibit we visited, but getting there was a challenge. Carsickness ran deep in our family. Complaining was not an option when traveling with my dad, so my brother and I would try to sit still in the backseat and grind out the nausea as best we could. There would be no warning. My dad would be driving along, deep in thought, as Billy and I in the backseat were slowly turning yellow in the face. All of a sudden, there was a splashing sound on the floor mats.

He would silently pull over to the side of the road, and we’d all get out to assess the damage. My brother or I would shake off our clothes as best we could (the rest would dry and fall off on the way up Bunker Hill), while my dad would take handfuls of dirt from the roadside and shake it over the mess on the floor mats, covering it with a layer of dust. Of course, none of this masked the smell; it just turned the wet vomit into dirty vomit. But it was a good try—real, American ingenuity at work.

Some might wonder why my brother and I were so afraid to ask our father for anything. The reason is simple: dads were meaner in the 1970s. Back then, fearing your dad was what you did. That’s why so many guys of my generation had such an attachment to Star Wars. We all remember that dramatic scene in The Empire Strikes Back, and the deep, chilling voice of Darth Vader as he confronts Luke Skywalker: “Luke, I am your father!” Boys like me everywhere were sitting in the movie theater clutching their popcorn bucket thinking, Yeah that makes sense… I can’t believe I didn’t see that one coming!

As much as the world was changing in the 1970s, the world inside our home was much like the America of decades past, or centuries, even. Think about it: our country was about to have its two hundredth birthday, and I’ll bet my dad wasn’t much different from George Washington’s dad; stoic, stern, and authoritarian. But George Washington turned out okay, and we would, too.

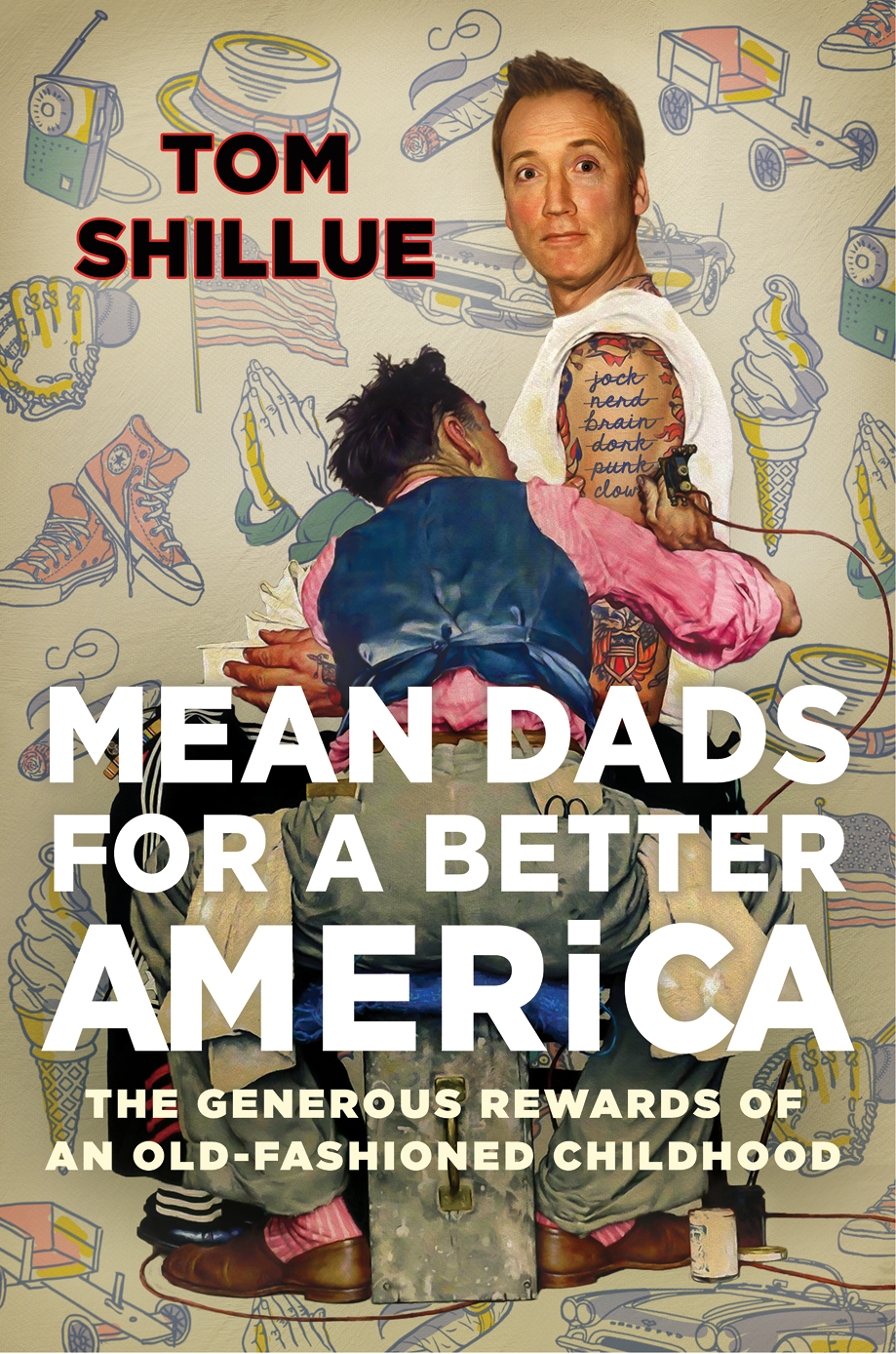

I understand that I had a great and fortunate childhood. I was not the victim of strict parenting, but a beneficiary of it. When someone hears me say “Mean Dads,” they might think, But my dad was mean and he ruined my life! But that’s a different story. Of course, real abuse is a tragedy, but what passes as “mean” today used to just be called “parenting.”

I spent much of my childhood in fear. Fear of God, fear of my parents, fear of the other adults in the neighborhood, fear of bullying kids. But fear is not always a bad thing—it keeps you alive. Fearing actual danger is very important. As you grow up you learn which fears are real and which are not, and it’s always liberating to discover when one of your fears is unfounded. You think, My dad is going to kill me when he finds out! But then he doesn’t kill you. You live to see another day. Your dad is not a murderer that’s great news to a kid!

Then you realize, Perhaps he wants me to think that he is going to kill me, so next time I’ll think twice before starting a fire in the garage. Dad worked in mysterious ways, like someone else I know. Fearing God is obviously important, but how are you going to fear God if you don’t fear your dad? He’s not God, of course, but for a while he’s a pretty good stand-in.

From MEAN DADS FOR A BETTER AMERICA by Tom Shillue. Copyright (c) 2017 by Tom Shillue. Dey Street, an imprint of William Morrow Publishers. Reprinted by permission.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- How Elon Musk Became a Kingmaker

- The Power—And Limits—of Peer Support

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com