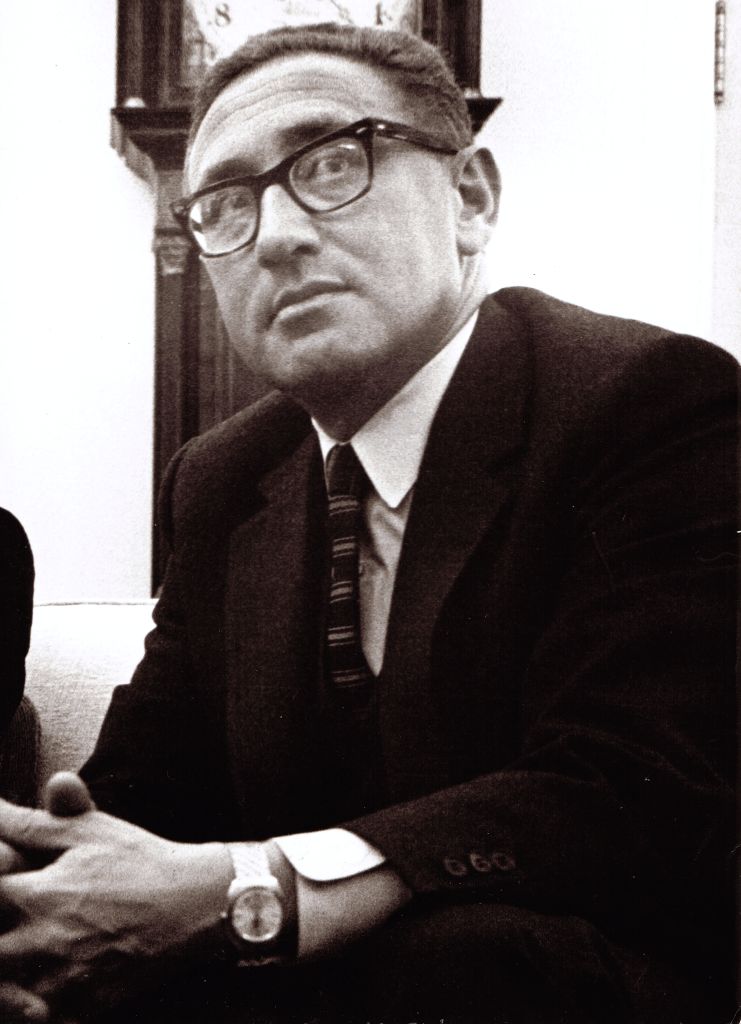

The first foreign-born U.S. Secretary of State, Henry Kissinger, who has died at 100, will likely be remembered most for his service as a diplomat in the 1960s and '70s, as an adviser to Presidents, or as the holder of a controversial record on human rights, based on his support for campaigns such as the U.S. bombings in Cambodia that killed tens of thousands of civilians during the Vietnam War.

But the public service of which he himself was proudest was of a very different sort. Though he rarely wanted to talk about it, Kissinger helped liberate a Nazi concentration camp.

Back then, Kissinger was a 22-year-old German-born Army Sergeant in the American 84th Infantry Division. Though he would later say that become a GI helped him to feel closer to his adopted homeland — to which he had immigrated as a teenager, before he changed his name from Heinz to Henry — fighting in Germany made his roots all too real.

"On April 10 [1945], just days before the roundup of the Gestapo sleeper cell, Kissinger stared the Holocaust in the face when he and other members of the 84th Division stumbled upon the concentration camp at Ahlem," Niall Ferguson wrote in his biography Kissinger, Vol. 1, 1923-1968: The Idealist, in which Ferguson republished Kissinger's two-page reflection on that day.

"I see the huts, I observe the empty faces, the dead eyes," Kissinger wrote. "You are free now. I, with my pressed uniform, I have lived in filth and squalor, I haven’t been beaten and kicked. What kind of freedom can I offer? I see my friend enter one of the huts and come out with tears in his eyes. 'Don’t go in there. We had to kick them to tell the dead from the living.'"

The experience, he wrote, exemplified "humanity in the 20th century," at a time when the very definitions of life and death seemed to blur.

Read more: Long-Forgotten Cables Reveal What TIME's Correspondent Saw at the Liberation of Dachau

More than six decades later, during a screening of a documentary about the camp, Angels of Ahlem, he said that seeing the victims was "one of the most horrifying experiences of my life." He knew that, had his family not fled Germany in 1938, he too could have been one of the victims of the Holocaust. It was a realization that would shape his worldview for decades to come.

He would later write to his father, according to Ferguson's book, to explain that he believed that it was important to be fair enough to prove that democracy worked, but "ruthless" to those who were responsibility for such acts.

And, when he became Secretary of State in 1973, he recalled that what his personal story had taught him: "There is no country in the world where it is conceivable that a man of my origin could be standing here next to the President of the United States. And if my origin can contribute anything to the formulation of our policy, it is that at an early age I have seen what can happen to a society that is based on hatred and strength and distrust," he said. "America has never been true to itself unless it meant something beyond itself. As we work for a world at peace with justice, compassion and humanity, we know that America, in fulfilling man's deepest aspirations, fulfills what is best within it."

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com