While Mother’s Day has been a national holiday since 1914, Father’s Day wouldn’t get the same legal status until more than half a century later, when President Nixon signed into law a measure declaring the third Sunday of June be observed as Father’s Day.

The proclamation acknowledged that it had already “long been our national custom to observe each year one special Sunday in honor of America’s fathers,” and Presidents had been making public statements in support of Father’s Day since the early 1900s. Annual celebrations for dads date back to 1910, when Sonora Louise Smart Dodd organized such an event to honor the life of her father, William Smart, a Civil War veteran and who raised six children on his own after his wife died in childbirth.

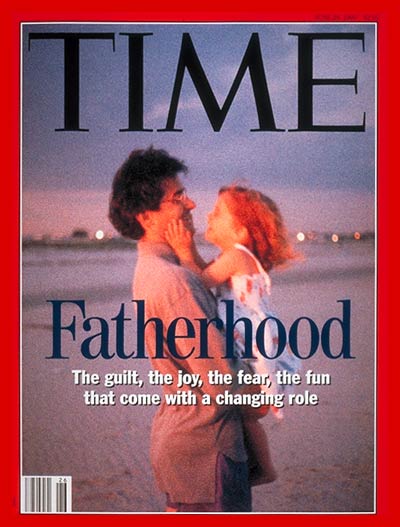

But things changed in the 1970s. Experts say that one crucial force was a major shift in how the American father was perceived.

The “New Fatherhood” movement developed in the early 20th century — in the midst of the temperance movement and concerns that urbanization was creating a generation of degenerates — as a growing body of research on child-rearing urged dads to support their kids not only financially but also emotionally, from changing diapers to playing with them to giving them life advice, as Ralph LaRossa, the historian behind the History of Fatherhood Project, notes in Deconstructing Dads: Changing Images of Fathers in Popular Culture.

As such, early iterations of the push for a national Father’s Day often focused on validating the importance of the father’s role in the family. For example, during the Great Depression, some saw Father’s Day as a way to boost the self-esteem of men who’d lost their jobs or had their wages cut — to show these dads they could still be there for their kids as a companion and male role model. Then, during World War II, when fathers were more likely to be away fighting, Father’s Day ads showed images of dads in uniform and touted the role of “the father as a protector” of home and hearth.

LaRossa argues that that same kind of valorization of the father as protector — though not necessarily as a physical presence in the home — may have been happening in the late ’60s and early ’70s too, during the Vietnam War, citing a section of the Congressional Record in which Montana Senator Mike Mansfield argued that Father’s Day deserved as much recognition as Mother’s Day got, because the “trying times” through which Americans were living placed new “burdens and responsibilities” on dads.

But Vietnam wasn’t the only thing happening at the time.

Another crucial element in the nationalization of Father’s Day was the women’s liberation movement, which offered women a forum in which to fight for the same workplace opportunities as those men were entitled to. For some, the idea of that equality had echoes in the home. As parents started to split the tasks of parenting more equally, it got stranger that mothers were celebrated in a way that fathers weren’t yet. “What seemed to be different in the late 20th century is the belief that dads should take on more of the routine tasks of taking care of kids, like changing diapers, and to do it in the interest of gender equality, which wasn’t as central a thing in the early 20th-century ‘New Fatherhood’ movement,” LaRossa says.

For others, however, the desire for a day for fathers was more about a backlash to the perception of the father’s place in the family slipping, suggests Timothy Marr, a professor of American Studies at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. “It was only after the Sexual Revolution and the establishment of no-fault divorce in the 1960s challenged the prominence and permanence of the father’s role in the home that Congress officially authorized a permanent observance in 1972,” he writes in American Masculinities: A Historical Encyclopedia.

Nowadays, while many parents are still working on mastering the perfect balance of gender equality in parenting in the 21st century, everyone seems to generally agree — thanks in part to the men’s clothing industry — that dads deserve a token of appreciation one day of the year, even as Americans continue to debate what a father’s responsibilities should be in the home.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com