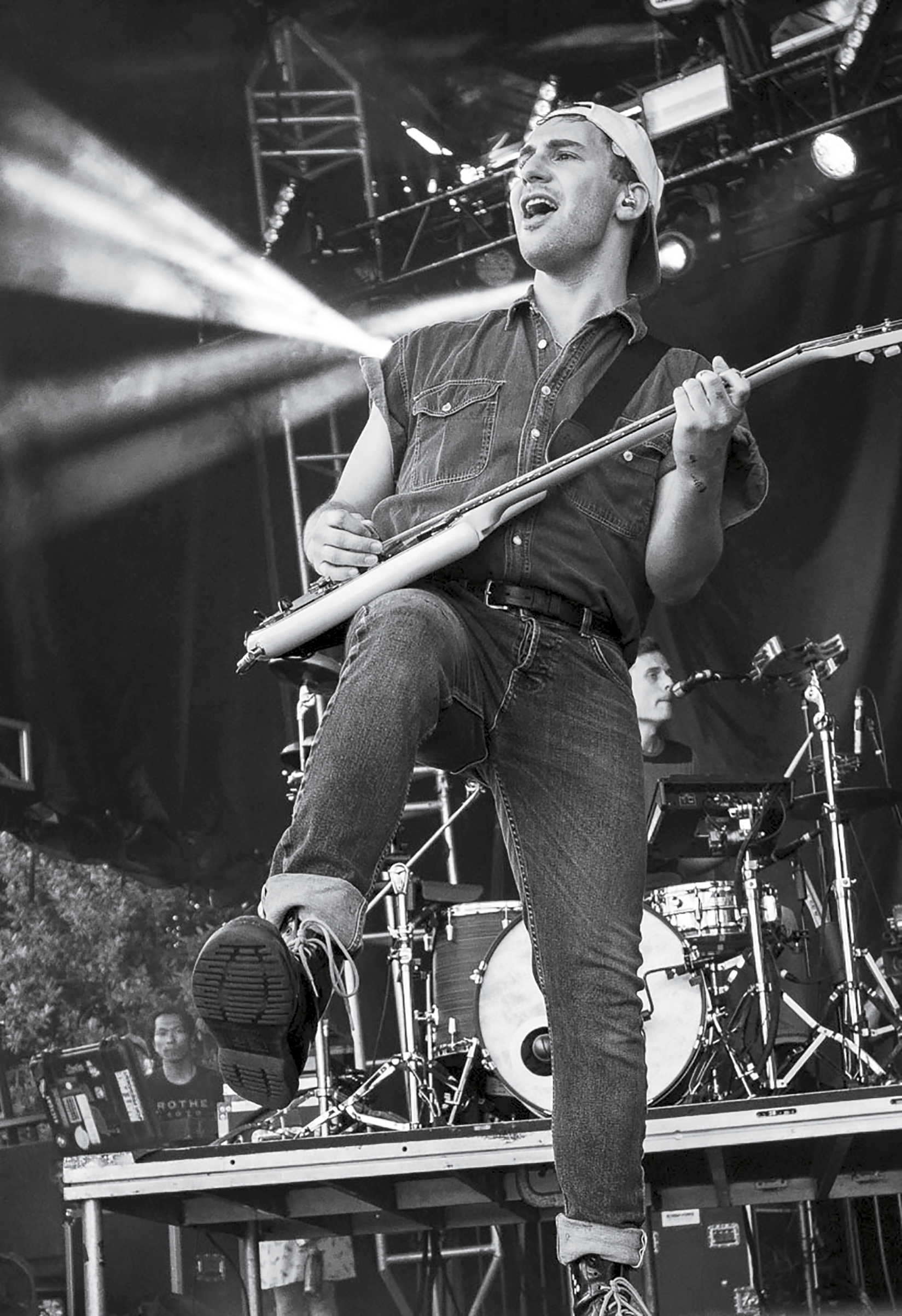

When Bleachers frontman Jack Antonoff arrives in your city on his upcoming tour, he’ll have something unique in tow: his childhood bedroom, painstakingly reconstructed in the form of a traveling art installation. It makes sense, since Antonoff is fascinated with the idea of baggage — mostly the emotional kind. “We all have this stuff we carry in an invisible suitcase,” he says. “You can’t keep it all, because if you keep it all, you can’t move forward. But you can’t let it go, because if you let it all go, you’re not yourself. The great balancing act of life is, What do I keep in here?”

Gone Now, his new album out now, offers answers. The music is deeply personal and more than a little bonkers — pop music without guard rails. (Antonoff calls it “the sound of a person going crazy alone in a room.”) For the 33-year-old singer-songwriter, who has been in bands since his high school days in New Jersey, it’s the opportunity to make music unfettered by anyone else’s creative impulses.

On a tour stop in Seattle, we meet for dinner and talk about how he made this new record, mental illness in pop culture and the cost of being a creative person.

TIME: You’re still based in New York, even though there’s been an exodus of artists to Los Angeles. Do you prefer it?

I love it more now that everyone left. It’s a better place to create than ever. I just don’t think it’s good to be around too much creative energy other than your own. That’s a weird fable of work — you don’t want to be in a crazy creative space. At least for me, any time I’ve been in hotbeds of creativity I got excited about something that wasn’t coming from me.

Sometimes when I look at production credits on a song, there are twelve writers on it. I don’t feel like your name is often one of twelve.

I’m not super social that way. That’s not my opinion of what makes it good or bad; that’s just what makes me good or bad. That’s always how I’ve made my own records — alone. So if I do a record with someone else it’s much more comfortable to have them come into my space than entering some bloated environment with lots of people and opinions. It’s the difference between crafting something vs. an assembly line. There’s glory in a big sports car, but there’s also glory in buying a button on Etsy. It’s not saying one or the other is better.

But it also means that work isn’t happening by committee. What you put out seems like it’s exactly what you intended to create.

That’s the goal. I’m not trying to write a perfect record. I’m just trying to nail a moment in time.

Is this an album about trying to decide what to let go of and what to keep?

It’s this big package and then you tie a little bow on top and the package is my whole life and every album is a giant funnel. The first Bleachers album was more like a diary. It read like: “Here is what happened. Here’s when it happened. Here’s why it happened. Here’s what it did to me.” It was so literal because I made it in headphones in a computer. This album has been more about where do you go from here. One thing I started looking at a lot on this album is how everyone has an end of innocence moment. For me I was eighteen, it was 9/11, my sister died, my cousin was killed in the war, and I had life before that and life after. Life before that was, “That shit happens to other people.” Life after was everything happens to me. You start getting on airplanes and saying to yourself, “It’s going to go down.” That’s the ultimate feeling of becoming an adult. You let go of the belief that it doesn’t happen to you. So how do you move forward? How do you exist in a relationship? How do you be 33 and not just a piece of sh-t who tours? I don’t want only that.

To me this album is also about the difficulty of being a person in the world who feels things deeply, which feels like a conversation that’s very timely. Why do you think that dialogue is playing out more in the public now?

First, it’s science. Just the literal science of anxiety and mental illness. You think in twenty years someone’s going to be like, “Oh, there’s dirt on my spoon — I’m having a panic attack?” I think that’s a serious thing. Even the lingo. “You’re such a psychopath.” “I’m sorry I’m such a schizo.” There are things in society that we don’t have tolerance for. We don’t have tolerance for single people, we don’t have tolerance for mental illness, and we don’t have tolerance for people with no god. At this moment I’m two of those people. I’ve been three of those people. Mental illness — we just started having that conversation. My grandparents got out of Poland right before the Holocaust and came here, and the only thing that mattered was surviving. Then my parents were more like, you go to work so you can have a good life. My generation was the first time we started saying, “Jack can’t focus at school. What’s wrong with him? Maybe he’s not a loser. Maybe we send him to a therapist and don’t tell him to be a tough guy. I see kids now and I’m almost envious of them because there is this conversation. You wake up one day and you don’t want to get out of bed? Maybe you’re not a loser. Maybe you’re not lazy. Maybe you’re depressed. A lot of those things I forgave myself for later in life.

Is healing something that you think about?

I don’t think about that at all. I don’t know what a version of healing would be once you’ve carried all these things forever. I don’t want to lose those things. I don’t want them to heal or change or get better. I want to understand them. Having panic attacks or dissociating — then I want to heal. So there’s a scale where it’s like — can you leave the house? Can you connect with people? Can you care for yourself right? If you can’t do those things, you have to heal. But everything else, I think, is an attempt to understand. I want to understand why I feel certain ways. I want to understand why I can’t do certain things and can do other things. I want to get myself the way I get other things.

But would you be as creative if you didn’t have parts of you that were underdeveloped?

I agree with you but after a time, it just gets tiring. I’ve never had a romantic connection to being a fu-ked-up artist. You start to miss out on things. Things got hard making this record.

How so?

You only have so much heart and soul to spread around and if you put it all somewhere, something else has to fall out of the suitcase. Writing is such a prisoner’s deal. You can’t just do it. You have to wait around for it. You have to put yourself in a space where it can happen. That space doesn’t give a sh-t if so-and-so’s wedding is that night. I don’t think that’s cool. I want to be there. Those are the things that you remember. “Remember when we went to the diner that one night and talked? Remember this person’s wedding?” You start to consider those things. You want to have all of them.

Where do you fall now on that spectrum?

The work is fun, but I felt bogged down by hearing things and trying to get them out. You know, I pray to hear things. I literally pray for songs. You can’t make them. You can’t fu-king make them! You can make a song, but nobody would care about it. It wouldn’t have heart and soul. Why do you hear one song and it defines what’s inside you, and you hear another song and it means nothing to you? You can’t define it, right? So I sit around and literally pray for those words and sounds and when they come it’s like your baby is being born. If you’re watching your baby come out of someone, you wouldn’t be like, “Oh, it’s Jimmy’s work party, I gotta go.” But at some point you gotta return to normalcy. So what happens if that happens twelve times a year? I don’t write a lot of songs. On this album, there isn’t one more song that I wrote. I never understood or had the capacity to write many songs and choose.

How long did it take you to finish?

Two years. I’ve always been that way. I need work. I always thought everything you do should be the best thing you’ve ever done.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com