The Kennedy clan’s dinner table has often been described as a place for heady intellectual discussion, and one can imagine the importance of image being one of the topics up for debate. Patriarch Joseph P. Kennedy had learned from his tenure as a film mogul that “image is reality,” but it took time for his second son, John, to learn that lesson. When he did, his definition of that image would be deeply tied to his own self-realization as a politician, especially through the emerging medium of television.

John Kennedy was most revealing about his conception of image in an article for TV Guide in November 1959, published several months before he ran for the Presidency. Kennedy writes about the general candidate, but clearly he is scrutinizing himself: “Honesty, vigor, compassion, intelligence — the presence or lack of these and other qualities make up what is called the candidate’s ‘image.’” He then questions intellectuals who scoff at these TV impressions, preferring instead the content of position papers. Kennedy is definitive in his belief that the images seen on TV “are likely to be uncannily correct.”

It was after appearing stiffly on several talk shows, notably Meet the Press, in the early ‘50s, that Kennedy learned how to craft such a TV image for himself. It is on full view on Person to Person with Edward R. Murrow in October 1953. Joined by his new bride, Jacqueline Bouvier, he switched within seconds from talking about the Taft-Hartley Act to his love of football. From then on, the personal would always be intermingled with the political.

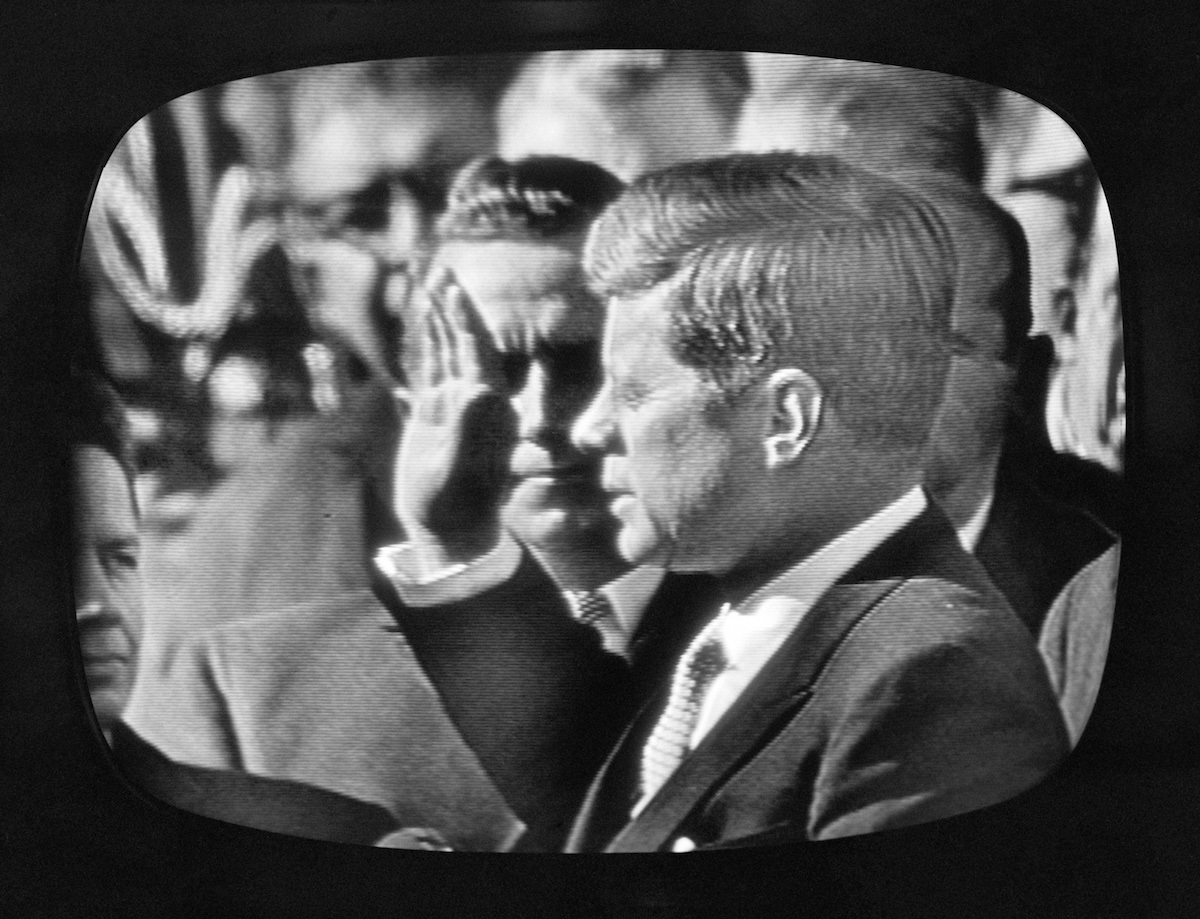

Kennedy was thrust into the national spotlight when he was selected to give the nomination speech for candidate Adlai Stevenson at the 1956 Democratic Convention. He and his writing partner Ted Sorensen threw out the suggested, cliché-ridden remarks, instead formulating a speech that foregrounded the themes that Kennedy would develop over the next eight years. He urged the party to unite around “the most eloquent, the most forceful, and our most appealing figure.” These qualities did not exactly define Stevenson, considered by many the quintessential urbane egghead, but they were certainly aspirational for the young senator contemplating his next four years. Impressing the television audience, Kennedy became the most sought after speaker of the Party, catapulting his presidential run.

Democratic Convention, John Kennedy, 1956:

Senator Kennedy courted controversy when he appeared on Jack Paar’s version of the Tonight Show while he was running for the Democratic nomination for president. No major politician dared to guest on a late-night program before, and no one was sure whether the equal-time rules applied to entertainment programming. Paar later recalled that the audience was immediately captivated by Kennedy’s visage: “they had never before seen such a young, attractive senator.” The program went so well that Jack’s father called next day to congratulate Paar.

JFK and Jack Paar:

The 1960 Presidential Campaign was a watershed moment in American politics, unleashing the “revolutionary impact of television” that Kennedy envisioned the year before in his TV Guide essay. Eschewing the physical demands of whistle-stop politicking, Kennedy went before the cameras to confront such major issues as his religion and relative inexperience. With television sets in over 90% of American homes, Kennedy preferred to press the electronic flesh.

The culmination of the campaign came with four historic debates between Kennedy and Richard Nixon. Few events have continued to be analyzed in such minute detail, from suit color to make-up to the sketchy polls afterwards. David Wolper’s documentary adaptation of Theodore White’s revelatory book, The Making of the President 1960, captures how a confident and well-prepared Kennedy was. Perhaps, to paraphrase Sun Tzu, every debate is won before it is ever fought.

The Making of the President (debate coverage begins at 45:35):

Five days after he took office, President Kennedy conducted the first live press conference on television, a high-wire act of great valor and vigilance. Many on his staff were opposed to such improvisatory dialogues, warning that a slip of the tongue could create an international incident. But the President had faith in his rhetorical ability, realizing his cool demeanor, in the words of historian Mary Ann Watson, “translated into a dignified, statesmanlike persona.” Over the course of 64 press conferences, he incarnated American democracy in action.

Studying taped copies of his press interactions, President Kennedy consulted with such television professionals as director Franklin Schaffner and producer Fred Coe to further improve his performance. He learned the nuances of political discourse so well that if often seemed he was simultaneously directing himself, a White House hyphenate of Orson Welles ambition. Watch how President Kennedy directed a 1963 taped interview with the most popular TV anchors of his era, David Brinkley and Chet Huntley, asking for a retake to several answers on Vietnam:

Outtakes from NBC Interview with JFK:

Much has been written about President Kennedy’s existential embrace of live TV, but he was as conscious of how his legacy would be preserved by documentary projects. He was the first president, and still among the few, to invite filmmakers to eavesdrop on meetings of national importance. In the cinema-verite film, Crisis: Behind a Presidential Commitment, Kennedy and his advisers discuss making a public pronouncement about racial integration, risking the loss of Southern support. Here, again, you feel President Kennedy as star and director, constructing his thoughtful countenance in the rocking chair for the present and for history:

In the room with JFK and RFK:

It was during Kennedy’s time in office that Daniel J. Boorstin published his unsettling treatise on national politics, The Image: A Guide to Pseudo-Events in America. He questioned the use of advertising to sell presidents, proclaiming that the image in U.S. culture has replaced the ideal, with the country now turned over to public relations experts. But, as we dissect the multi-dimensional TV images of President Kennedy over his evolving career in politics, we see a leader deploying his image in all forms of television to further American ideals of justice and fairness. His image, far from being the façade of which Boorstin warned, conveys profound realities.

Historians explain how the past informs the present

Ron Simon is Curator, Television and Radio, at the Paley Center for Media.

To celebrate the centennial of the birth of John F. Kennedy, The Paley Center for Media and the John F. Kennedy Library Foundation are gathering journalists, analysts and historians on June 13th to assess how Kennedy and his administration transformed the presidency using television as an essential political tool, from campaigning for the office through governing a nation. The Paley Center has the complete programs of the links that curator Simon references in his essay.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com