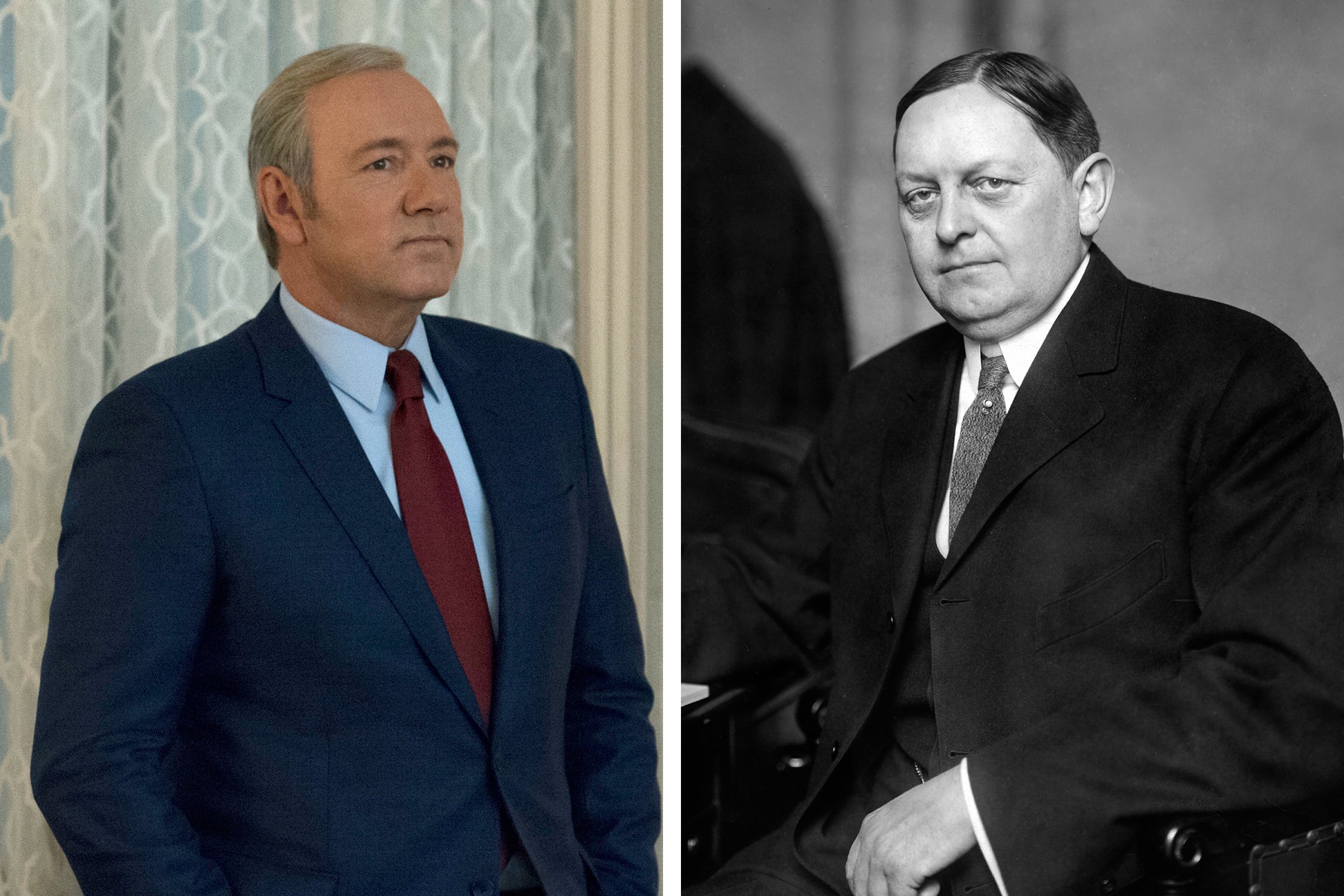

To political junkies these days, the only “Underwood” in politics is Francis Underwood, the conniving House Majority Whip-turned-President played by Kevin Spacey on the hit Netflix political drama House of Cards, the fifth season of which starts streaming Tuesday.

It’s thought that Underwood takes his name from that of a real Southern Democratic House Whip — and one who could only dream of being president.

Oscar Wilder Underwood, a Louisville, Ky., native who practiced law in Birmingham before being elected to represent Alabama in Congress from 1895 to 1927, is “the only person to serve as Democratic leader in both the House and Senate, and the first Senate Democrat to be officially designated as his party’s floor leader,” according to the Senate Historical Office. While chairing the House Ways and Means Committee, he lent his name to the Underwood Tariff of 1913, the first significant tariff reform since the Civil War. Designed to bolster international trade, it “broke 52 years of Republican protectionism and provided for the first Federal income tax levied under the new ratified 16th Amendment,” according to a history of the committee. In Congress, he was known for supporting states’ rights, and the League of Nations, but he turned down the opportunity to run to be Woodrow Wilson’s vice president in 1912 (an office he probably would have won, TIME suggested in 1925). He was elected to the Senate in 1914.

His views on social issues set up him to fight for his life in the election of 1920.

He opposed women’s suffrage, organized labor and the Ku Klux Klan, and was known as a “moist” or “wet” conservative Democrat, meaning he was against prohibition. By today’s standards, he might be considered a Libertarian, according to Wayne Flynt, a historian whose 2016 Southern Religion and Christian Diversity in the Twentieth Century has a chapter on Underwood’s 1920 Senate reelection campaign. Issues like suffrage and prohibition, as TIME once summed up in describing Underwood’s political views, seemed to share “lofty purpose, great zeal, and not a little oratory” but Underwood saw “something dangerous in them all.”

He barely won re-election because so many people who supported those issues came out to vote against him. “Alabama was the largest manufacturing state in the South and had the largest union membership at the time,” Flynt explains, and those same people were often both prohibitionists and Klan members. “And he hadn’t counted on the 19th amendment passing, and so a huge influx of women turned out against him.”

His personality is thought to have gotten in the way too because, unlike the fictional Underwood, he didn’t have the charisma and ability to make connections with working-class people. “He was not very affable man, and that’s another reason he nearly lost,” Flynt says. He also supported poll taxes and other voter-suppression methods designed to keep working-class whites and African-Americans from voting, so he didn’t think it would matter whether they liked him or not.

Though he did win reelection in the end, Flynt notes that he was “damaged goods” after barely carrying his home state, which took “a lot of the luster off of his reputation as someone who would sweep the South.”

Yet, like the fictional Underwood, he aspired to higher office — meaning the highest office — no matter. He decided to run for president in 1924, noting in a speech that he was “going to give the South a chance to select a Southern man to carry the banner of Democracy.” He earned household-name recognition for being one of the key players in the longest-running national political party convention in U.S. history, during which the Alabama delegation put 24 votes toward his candidacy during each and every one of the 103 ballots. Still, the Democratic Party’s nomination went to someone else, John W. Davis.

And, while the fictional Frank Underwood’s father’s ties to the KKK threaten his presidential campaign in House of Cards, historians say that Oscar Underwood’s failure to be nominated can be traced to his denouncement of the KKK, which ended up costing him Southern support. “Although the Klan ridiculed Underwood as the ‘Jew, jug, and Jesuit’ candidate, the national press extolled his statesmanship, tolerance, and courage,” according to Flynt’s book Alabama in the Twentieth Century. After that drama, he lost his seat in the Senate too.

Though never president, he died in 1929 at a residence fit for a president: Woodlawn Plantation in Virginia, which was once owned by George Washington.

Political scientists argue, however, that — minus the corruption — the fictional Underwood’s path to the presidency doesn’t resemble the real Underwood’s career so much as that of Gerald Ford, who became President without ever having been elected to the White House.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Biden Dropped Out

- Ukraine’s Plan to Survive Trump

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com