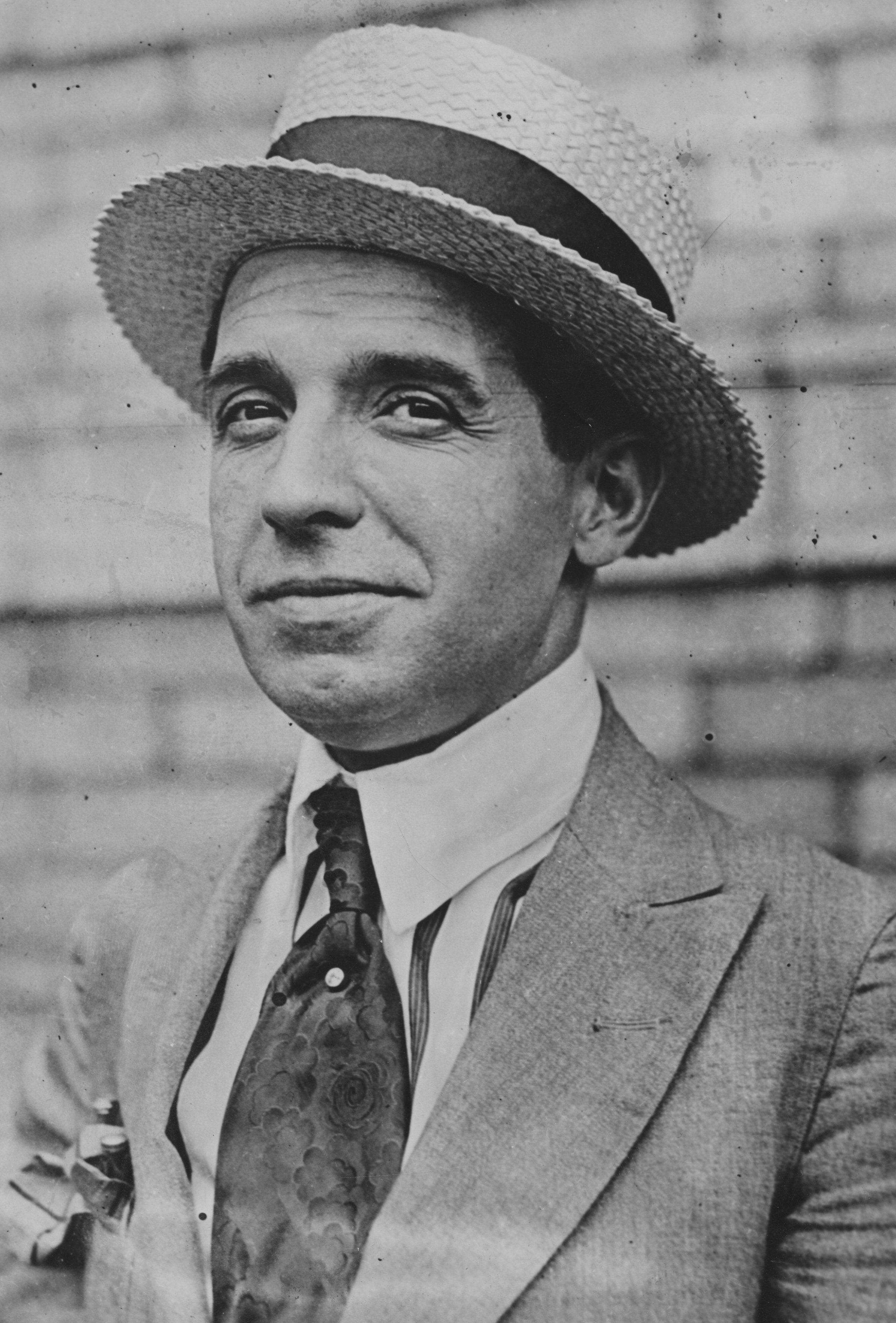

When HBO’s The Wizard of Lies airs on Saturday, starring Robert De Niro as Bernie Madoff, it will be just the latest moment in the century-spanning history of the scheme that earned Madoff a 150-year prison sentence. It all began with Charles (or Carlo) Ponzi, a five-foot-two-inch Italian immigrant in Boston, who, in 1920, landed in jail for defrauding about thousands in the Northeast of at least $15 million — or about $190 million in today’s dollars — over the course of just eight months.

Ponzi scheme started with “postal reply coupons,” which could be used to buy a stamp in any country in the world. He had figured out that “if you could get these coupons in one country, where the currency was depressed, and trade them in a place where the currency was strong, you could make a fortune. You could buy cheap and sell high,” says Mitchell Zuckoff, author of Ponzi’s Scheme: The True Story of a Financial Legend.

Ponzi promised clients a 50% profit in 45 days, and a full return in 90 days. The line to invest with him grew so long in Boston that 20 police officers were dispatched for crowd control. A July 29, 1920, article reported “Exchange Wizard” Ponzi was a hit with the mob that day for distributing free hot dogs and coffee for those waiting to get their money back. “I want to use my customers right,” he said as the food was being distributed. “There is nothing for them to fear.” At one point, it was reported that he kept the money in “wastebaskets after his desk drawers overflowed.”

But there was a problem, Zuckoff explains. “[Ponzi’s idea] was logistically impossible because there weren’t enough coupons in circulation. There wasn’t a way to transfer them into cash.” Because Ponzi couldn’t get a loan to support his business and the coupon trade wasn’t actually making the money he’d promised it would, “he decided to use money from new investors to pay old investors what they were due,” all the while claiming that the money was from returns on the coupon market.

The Boston Post won a Pulitzer for exposing his scheme, thanks to a tip that City Editor Eddie Dunn got from one of Ponzi‘s disgruntled press agents. The newspaper reported that Ponzi was actually a Canadian ex-convict, whose previous crime had been dealing a forged check. Turns out he had learned how to defraud customers from a Montreal banker who had been tricking clients in a similar way.

Ponzi’s scheme forced several Boston trust companies to close — the biggest of which was Hanover Trust Co. Four years later, he was convicted on a state charge and sentenced for seven to nine years.

Though Ponzi gave his name to the idea, he didn’t invent this type of fraud, and we may never know who did. (For example, Brooklynite William Miller had became infamous in 1899 for promising a 520% rate of return to investors who shelled out $1 million.) But between the aforementioned publicity stunts, and the fact that he was charismatic and super quotable — “As I say, I landed in this country with $2.50 in cash and $1,000,000 in hopes” — he got the most media attention, so he’s the most well-documented example of this type of fraud. When he did get $1 million in his pocket, he brought his mother over from Italy to show her how well he had done, Zuckoff says.

And the timing of Ponzi’s scheme, as the economy was in an upward swing in the aftermath of World War I, made people especially vulnerable to fraudsters. “Those were confused, money-mad days. Everybody wanted to make a killing…My business was simple. It was the old game of robbing Peter to pay Paul,” Ponzi admitted to an Associated Press reporter on his deathbed.

“These types of speculative schemes increase when the economy is doing well, and people see other people, their neighbors, getting rich, so they think, ‘Well, why not me?'” says Gerard Caprio, professor of economics at Williams College. (For example, some of the worst Ponzi schemes in history were pulled off in Romania and Albania after the fall of communism, when people in eastern bloc countries “were coming out of desperate poverty, so they were more susceptible to such claims.”) Plus, in Ponzi’s time the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) hadn’t been created yet, so there weren’t very many protections against these kinds of schemes.

After the final payment was made to Ponzi’s creditors in December 1930, the first issue of TIME in the new year described him as the “duper extraordinary, personification of quick riches,” whose “wrecked web” earned him a place in “glittering in the archives of financial fraud.” The article recapped his crimes, a description of his appearance from the police description — “Age: 44. Height: Five feet two inches. Hair: Dark chestnut mixed with grey. Eyes: Brown. Occupation: Thief” — and reported that he “slept in lavender pajamas” when he lived at his spacious home in Lexington, Mass. It also claimed that he was “popular” for “his ability to write amusing verses about other prisoners and the jailers.”

Well, he saw that article, and wrote “amusing verses” back in a letter to the editor that was published in a following issue of the magazine, addressed from “Massachusetts State Prison Charlestown, Mass.” The juiciest bits:

Sirs:

I have read your article on “Ponzi Payment” in TIME, Jan. 5. Found it interesting, but none too accurate. My hair is neither chestnut nor grey. It’s gone. Have never worn lavender pajamas nor pink ribbons on my night shirt. Fur coat and overshoes on extremely cold nights have been my limit.

The police description looks rather spiteful. Perhaps the product of some minor minion. Almost invites retaliation. What ingratitude!…

If you desire certified copies of auditors’ reports, I have them. You may peruse them and weep. Your statement that the destruction of my wrecked “web” brought down several Boston trust companies is perfidious. Under any other form of government, it would call for a challenge to a duel. For this time, I shall refrain from perforating your hide on condition that you make public amend by printing this letter verbatim…

You know, I like you in spite of your jabs because you have given me an opportunity of spending an hour writing this letter. If you come over to Boston after I am out, I have a good mind to buy you a drink. Two, if you can stand the gait. Will you libate with me? Will you honor me by your acceptance? That is, unless you are a fanatic upholder of the “noble experiment”…

Ponzi was released from prison on parole in February 1934, and deported to Italy in October of that year. “I am not bitter,” he told reporters before boarding the S.S. Vulcana carrying a briefcase of newspaper clippings. “I went looking for trouble, and I got it, more than I expected.”

A few years later, he took a job in Brazil, and died in Rio de Janeiro in Jan. 1949. “He left an estate of $75, which was barely enough to bury him,” LIFE magazine reported in a full-page obituary for him.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- TIME’s Top 10 Photos of 2024

- Why Gen Z Is Drinking Less

- The Best Movies About Cooking

- Why Is Anxiety Worse at Night?

- A Head-to-Toe Guide to Treating Dry Skin

- Why Street Cats Are Taking Over Urban Neighborhoods

- Column: Jimmy Carter’s Global Legacy Was Moral Clarity

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com