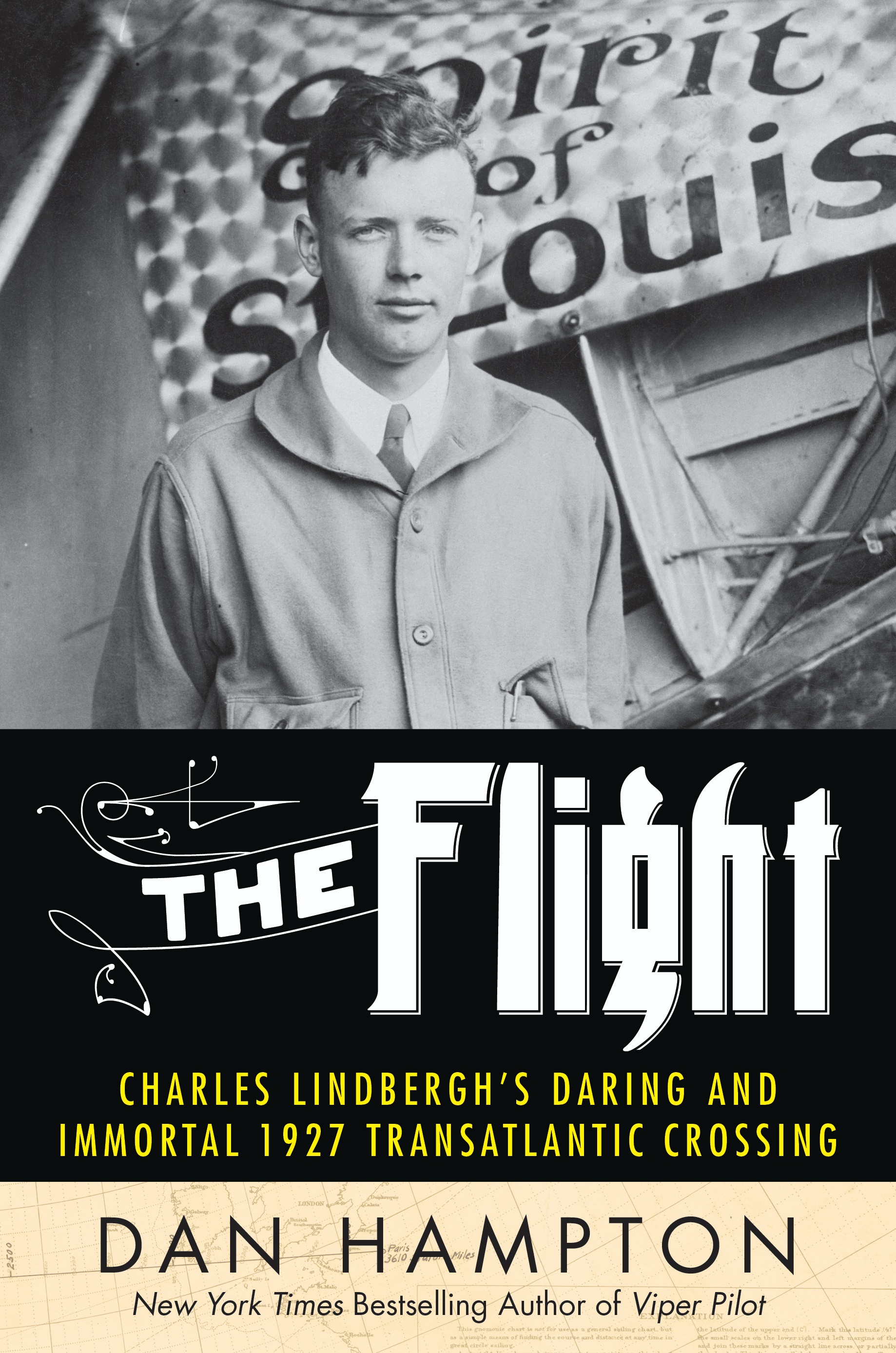

When Charles Lindbergh made history 90 years ago this weekend — on May 20 and 21, 1927 — by becoming the first pilot to fly solo nonstop over the Atlantic, the world was watching. It was, as TIME reported the following week, “news that would set thousands of printing press in motion, news that world make sirens scream in every U.S. city, news that would cause housewives to run out into backyards and shout to their children: ‘Lindbergh is in Paris!'” It was also news enough to make Lindbergh TIME’s first-ever Person of the year. But the world in which his feat was hailed was undergoing newsworthy changes of its own. In this excerpt from his new book The Flight, Dan Hampton explores the world that produced Lindbergh’s accomplishment:

With the industrial expansion to manufacture war material spiking prosperity, and a comparatively light loss of 53,402 combat deaths, the United States ended the war in a relatively strong position. On November 11, 1918, the State Department announced to newspapers on the American East Coast that the war had officially ended. Bells began to toll, and as the country awakened people in every city began celebrating. Businesses closed “For the Kaiser’s Funeral.” The Kaiser was burned in effigy and his dummy was washed down Wall Street with fire hoses. Sirens wailed and horns blared while people cried and laughed. Eight hundred female students from Barnard College snake-danced in Morningside Heights and a young girl sang the Doxology in Times Square.

The first 3,500 American soldiers arrived home at New York’s West Fourteenth Street pier aboard the Cunard liner Mauretania on December 1, 1918. Other ships followed in quick succession to bring back the two million troops deployed to Europe. Amid flags and colored bunting the soldiers marched down Fifth Avenue, swinging in step with fixed bayonets under an immense plaster arch at Madison Square.

Lights blazed again and Broadway was once more the “Great White Way.” Wartime censorship ended, sugar was no longer scarce, and real bread reappeared. Women were still wearing their hair long with high patent leather shoes over black or tan stockings, and skirts still stopped a modest six inches up from the ground, but all of this was changing. The 1920s were alive with change of every sort and, as is usually the case, it was unsettling to those living through it. To begin with, the normal intergenerational rebellion was exacerbated by a wartime mentality that wasn’t particularly interested in looking far into the future. What was the point, young men who became soldiers asked, if they had an excellent chance of dying on a battlefield? And why, young women then wondered, should we wait for men who might never come home? Why not, both sexes asked in increasing numbers, live for today and enjoy life while we have it?

Automobiles were becoming more common and were a way to escape supervision of parents, neighbors and, of course, spouses. Only 10 percent of cars were enclosed in 1919, but by the time Lindbergh flew the Atlantic this had jumped to nearly 83 percent. “Sex and confession” magazines were popular; Bernarr Macfadden’s racy magazine True‐Story sold two million copies annually by 1926 and was wildly successful. Yet the decade was hardly as gloomy and crass as it is often viewed. Walt Disney incorporated his first film company, Laugh-O-Gram, and Olympian Johnny Weissmuller swam the 100-meter freestyle in under a minute. The Lincoln Memorial was dedicated, carvings on Mount Rushmore began, and an eighteen-year-old named Ralph Samuelson became the first water-skier.

Illiteracy would decrease from 6 percent overall in 1920 to 4.3 percent by decade’s end. Capitalizing on the trend, TIME magazine would begin publishing in 1923 and create its “Man of the Year” in 1927. The New Yorker hit the street in 1925, and by the summer of Lindbergh’s flight more than 36 million newspapers were read each day. This newfound voracious appetite for the written word made it possible for the nation to closely follow Lindbergh’s flight, though, as he himself would ruefully discover, journalists sometimes placed sensationalism above accuracy.

Automobiles sat outside 10 million homes, and there were more cars in New York City alone than in Germany, and France had fewer automobiles than Kansas. Home to the largest publishers and banks, New York’s Woolworth Building at 792 feet was the world’s tallest structure, and the 8,558-foot Hudson River Vehicular Tunnel was the longest underwater tunnel on earth. New York had also surpassed London in terms of population, and 40 percent of U.S. international trade passed through its port.

It would be simplistic and incorrect to believe the nation suddenly rejected its values and, as is popularly portrayed, abandoned its past and future for the present. Many certainly did not go on benders, cut their hair, wear short skirts, or ditch prewar notions of morality. But many did. A tremendous labor shortage had occurred when the men joined up to fight, and the vacuum was largely filled with women and black men, who had become temporarily accustomed to the relative independence provided by a steady income.

When the soldiers came home and were demobilized, they wanted their jobs back and a return to the old social order. But many women resisted falling back into domestic servitude, and black men had shown they could perform as equals in every facet of American life—if they were permitted to do so.

Labor unions, highly influential at the time, found them- selves at a crossroads. Should they protect only white workers, which would reduce their collective bargaining power with big business—or should they represent all workers regardless of color? By generally choosing the latter, they fed racial resentment among whites, bringing organizations like the Ku Klux Klan back to life. By 1920 the Reverend William J. Simmons, a former Methodist minister from Alabama, had increased the Klan’s membership to more than four million. As their influence grew, so did their sense of self-importance; like the Taliban of a later era, they saw themselves as the sole guardians of “pure” American life. “Native, White, Protestant supremacy” became a motto, with dancing, drinking, religion, and any moral issues falling within their self-appointed purview.

They were not alone in this myopic, intolerant Puritanism. Some of the fanatics, like Wilbur Glenn Voliva, were silly. Head of the Christian Apostolic Church, Voliva stated in 1922 that “the sky is a vast dome of solid material, from which the sun, moon and stars are hung like chandeliers from a ceiling.” Others were not so easy to dismiss. During the war’s closing years, and those immediately following the armistice, enthusiasm for various forms of extremism was viewed by many as a counterweight to social change. Speaking German was made illegal in several states, books were burned, and in Boston, of all places, Beethoven was banned. In Collinsville, Illinois, a young man named Robert Prager, who happened to be born in Germany, was stripped, wrapped in an American flag, and lynched. His murderers were acquitted of this “patriotic crime” in only twenty-five minutes.

From The Flight: Charles Lindbergh’s Daring and Immortal 1927 Transatlantic Crossing by Dan Hampton, on sale now.

Reprinted with permission from William Morrow/HarperCollins

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Biden Dropped Out

- Ukraine’s Plan to Survive Trump

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Contact us at letters@time.com