When the Frank family first moved to the Netherlands, as Nazi power began to rise in Germany, they hoped that they had found an escape from a homeland in which they, as Jews, were no longer welcome. Though life in Amsterdam got off to a good start — Otto Frank’s business was successful, and his daughters Margot and Anne made good friends — it didn’t last. As the 1930s ended and German forces threatened the Netherlands, Otto sought a way to get his family out — or, failing that, a place for them to hide. The following is an excerpt from LIFE’s new special edition, Anne Frank: The Diary at 70, available on Amazon and at retailers everywhere.

On May 10, 1940, everyone’s fears came true.

Germany launched what it called Fall Gelb, an attack on the Netherlands, France, Belgium, and Luxembourg. On the 13th, Dutch queen Wilhelmina and her cabinet fled, asking her subjects to “think of our Jewish compatriots.” The next day, German bombers set off a firestorm in Rotterdam that killed nearly 900 people and destroyed more than 27,000 buildings. The Dutch commander in chief, General Henri G. Winkelman, had no choice but to surrender.

Some 140,000 Jews lived in the Netherlands, and the geography made it difficult to flee. Reichskommissar Arthur Seyss-Inquart ran the new civil administration and, at the start, many hoped that the occupying forces would not undermine day-to-day life. “When the Germans came in May 1940, they seemed to be proper men,” recalled Joop Zoutberg, a non-Jew whose father worked in Amsterdam’s matzo factory. “They did no harm that first time.”

But repressions quickly began under SS general Hanns Rauter, who headed national security. Regulations barred Jews from civil service jobs, forced them to disclose their business assets, and segregated Jewish children to all-Jewish schools. “Jews Prohibited” appeared on signs in parks and cafés. [Anne’s friend Eva] Schloss bristled at the restrictions: “At first it was a nuisance; we couldn’t go to the swimming pool or public transport or the cinema.” The movie rule especially bothered the cinema-obsessed Anne, so Otto rented movies and a projector to show films at home.

Then, in January 1941, the Germans required Jews to register in order to compile a record of the country’s 159,806 Jews and 19,561 mixed Jews. “This was a system of self-reporting. So anybody with Jewish grandparents had to report that to the authorities,” Gertjan Broek, a historian at the Anne Frank House in Amsterdam tells LIFE. “Strange as it seems today, most people just did that.”

Some joined the resistance, stealing ID cards and working with the Allies to sabotage bridges. And, after Germans assaulted Jews in the central square in February 1941, the Communist party called for a massive work stoppage. The action, instead of weakening the resolve of the Nazis, only inspired more repression. General Rauter crushed the strike, killing seven and wounding 76; 427 were apprehended and sent to the Buchenwald concentration camp.

Throughout, Otto’s business grew. Needing more space, Opekta moved in December 1940 to a new address: Prinsengracht 263, an early-18th-century canal building near the famed 17th-century Westerkerk church. The narrow brick structure had four stories and was actually made up of two buildings, one of which was an annex in the back. Because of the growing restrictions on Jewish life, Otto quietly transferred control of his business to Jo Kleiman and Victor Kugler.

By now, the Nazis had explicitly laid out their plan to exterminate European Jewry. And, in early 1942, with the United States having entered the war in the wake of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the Nazis cracked down even more. They issued 569,355 yellow stars marked Jood and required Jews to sew them onto their clothes. “My brother, Heinz, told me that a friend of his who took off his star got arrested and he was never seen again,” says Schloss.

With escape from Holland beginning to seem impossible, Otto Frank came up with a different idea.

He began, with the help of Kleiman and Kugler, to hatch a plan to hide his family in Amsterdam. As a child, Miep had been a refugee, having been sent by her parents from Vienna to Amsterdam following World War I, when there was little food to be had in Austria. So when Otto asked her and Jan, whom she had just married, whether they were willing to take responsibility for a family in hiding, they unhesitatingly said yes. Bep Voskuijl soon became part of the group of helpers, and Otto invited Hermann van Pels and his family to join them in hiding. They created a small apartment in the back building at 263, behind the office. To prepare the place, they surreptitiously stocked it with canned goods, dried fish, grains, and other necessities, as well as furniture, bedding, kitchen utensils, and dishes.

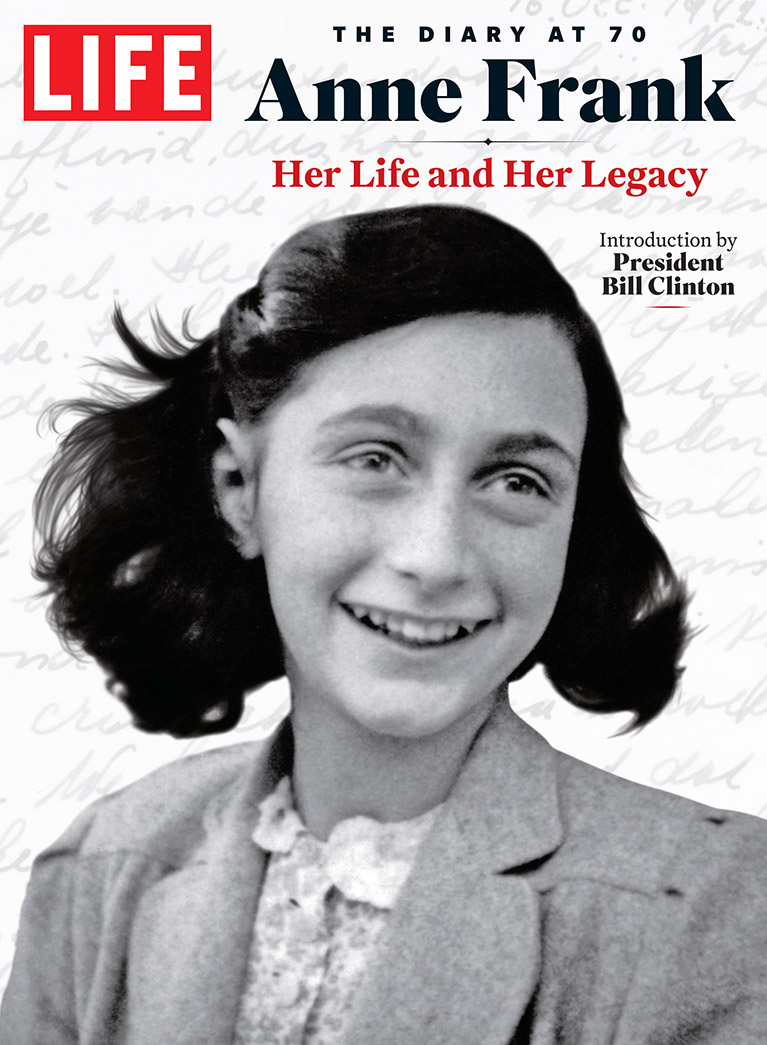

Anne turned 13 in 1942, and for her June birthday party, Otto rented The Lighthouse by the Sea, starring Rin Tin Tin. Anne had recently admired a red plaid diary at a book- shop around the corner from their home and was thrilled to receive it as a gift. She called the book “one of my nicest presents,” making her first entry that day, writing, “I hope I will be able to confide everything to you as I have never been able to confide to anyone. And I hope you will be a great source of comfort and support.”

Anne treated her entries like letters, eventually settling on an imaginary correspondent named Kitty, named for a character from a series of stories by Cissy van Marxveldt about a fun and carefree teenage girl with a best friend named Kitty. Despite what was going on around her, Anne stayed positive, heading with friends to Café Delphi or a local ice cream parlor, playing table tennis, and filling the diary’s early pages with teenage thoughts about her crushes and friends.

On July 5, however, a letter arrived from the authorities for Margot.

Plans had been announced to send Jews age 16 to 40 to Germany for labor, and Margot was now being ordered to report. That night Jan and Miep picked up some clothes, towels, and shoes. The girls packed their school- bags—“the first thing I stuck in was this diary, and then curlers, handkerchiefs, schoolbooks, a comb, and some old letters,” wrote Anne. Otto sent a coded letter to his sister, Helene Elias, in Basel, Switzerland, to let her know that they were going to vanish.

“We knew then that they were going to hide,” her son, Bernhard, would later say. “But we had no idea where. And from then on, there was no contact anymore.”

Read more in LIFE’s new special edition, Anne Frank: The Diary at 70, available on Amazon and at retailers everywhere.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com