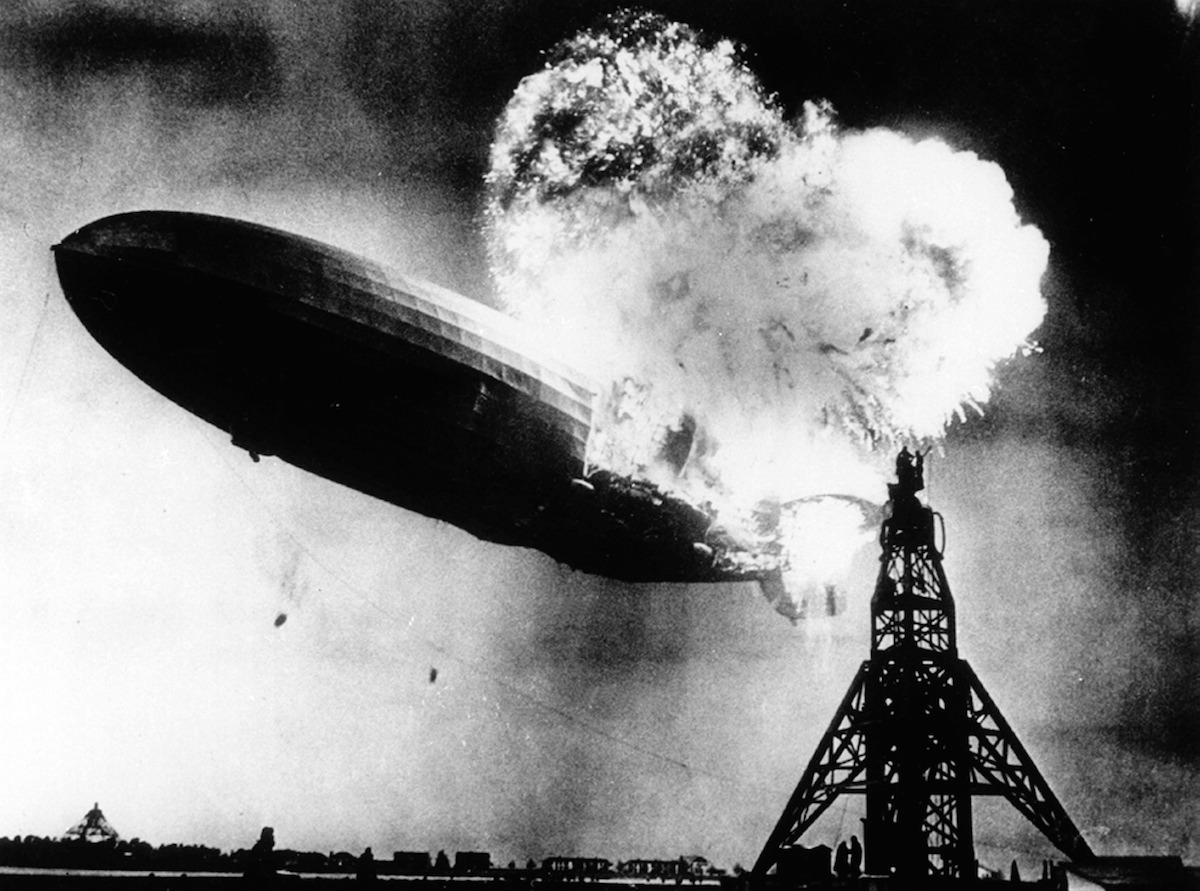

Every May 6, calendars mark the crash of the German dirigible Hindenburg at Lakehurst, N.J., in 1937. As the 80th-anniversary commemoration looms for the accident that killed 35 people, I am often asked why popular culture still acknowledges the disaster. After all, the world has witnessed far more serious air crashes, and in an age of instant media, online footage of carnage appears a dime a dozen. Why is it worth remembering?

Hindenburg’s crash was a participatory catastrophe. Very few people flew at the time, but most who heard the reporter’s cries or viewed the footage in news reels felt connected to the event, one that questioned the power of technology. Long before the age of social media, the filter of a catastrophe’s sound and images closed the airship age for good.

The Hindenburg was a symbol of progress in an era when Lindbergh’s flight across the Atlantic was barely a decade old. The behemoth’s aerodynamics were second-to-none. To see something as long as the Titanic floating in the air quietly with passengers waving must have created a sublime effect, much as Americans who have witnessed a space launch speak in awe of their experience. It flew longer, farther and carried more than any other contemporary aircraft. It also flew slower than Texas’ highest speed limit (85 mph).

Though we now know that the days of the giant dirigible were numbered, the last iteration of Count Zeppelin’s company models was comfortable, quiet and stable. One did not get airsick onboard. One could smoke (in a special compartment), eat off fine china or enjoy a piano concert while overtaking ocean liners a few hundred feet below.

While her lineage includes the first strategic bombers, Hindenburg was in fact a ship of peace, marketed as a business tool and as a way to strengthen relations between communities. Though the swastikas applied to her fins were a dark omen, in 1936, when Hindenburg first took to the skies, Nazi Germany was often viewed with an admiration that ignored the disappearance of German democracy or the persecution of Jews and all enemies of the regime. Hindenburg was one of the artifacts that masked the darker facets of Nazism, much as the Nazi Olympics and the German Autobahn did.

The German government understood this all too well, and borrowed from its democratic predecessor the image of modernity by subsidizing heavily the construction of Hindenburg and her flights. The trope worked. The American embargo on helium exports to Germany was papered over, and the airship was modified to use hydrogen. Even the bitter French and the nervous Swiss appreciated the opportunity to watch Hindenburg fly over their territories on her way across the Atlantic. Like Titanic on her maiden departure, Hindenburg projected invincibility, especially in the wake of her first flying season in 1936. The bleakness of the world’s economic and political situation cast the airship into a welcome respite of fantasy. In an era when the magic of flight still charmed contemporaries, it helped mask the heralds of war.

The brief seconds of the flight we now witness followed by the comment of the radio correspondent wailing “oh the humanity” are etched in human memory. We feel a connection because the newsman reacted like a human being. He was fired for his brief display of emotion, yet today, we remember that phrase above all.

What is left of the tragedy amounts to an odd mix of media-filtered snippets and ongoing fascination with the airship. Hopes of a new airship age keep enthusiasts wondering, but when it is not lack of funds that prevent the latest project from coming to fruition, the laws of physics and air traffic put an end to speculation. The true giant airship filled with frolicking passengers remains a fantasy of both the past and the future.

The heavy nostalgia that affects talk of the airship era masks other possible meanings of Hindenburg’s demise.

Beyond the metaphorical “end of an era” some novelists and movie makers have emphasized, it signaled the need for more efficient and safer air travel. Her crash was among the first to provoke a call for a methodical investigation that took months to complete, especially because of its political dimensions. This was also one of the first times the media and the public took an interest in technical discussions, ranging from unsecured airfield perimeters to checklists that might prevent crew complacency. These would eventually join a long list of safeguards aviation adopted as it matured, albeit too late to give the airship age a boost. Beyond the nostalgia they may elicit, media events do often have hidden impacts.

Guillaume de Syon is a professor of history at Albright College in Reading, Pa. He is the author of Zeppelin! Germany and the Airship, 1900-1939 (John Hopkins Press, 2007).

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com