Baltimore Orioles outfielder Adam Jones received a standing ovation at Fenway Park on Tuesday night, one day after facing racist heckling in Boston. The Red Sox fans who rose to their feet attempted to send a message: we want to shed the team’s reputation as a haven for racism.

Baseball Commissioner Rob Manfred said on Tuesday that the Red Sox have “made it clear that they will not tolerate this inexcusable behavior.” But this notoriety has dogged the team for decades. The precise reasons why are complicated, as is the question of whether the Red Sox are really any worse in this department than any other team. But there’s no question that Boston’s racist reputation has taken root.

“It’s almost an impossible thing to shake,” then-Red Sox president John Harrington told Sports Illustrated in 1991. “I don’t know how you do it. I’ve been told it will take 50 years, generations, before this thing is gone. I won’t be around and you won’t be around. It’s just impossible.”

Read more: Why Boston’s Sports Teams Can’t Escape the City’s Racism

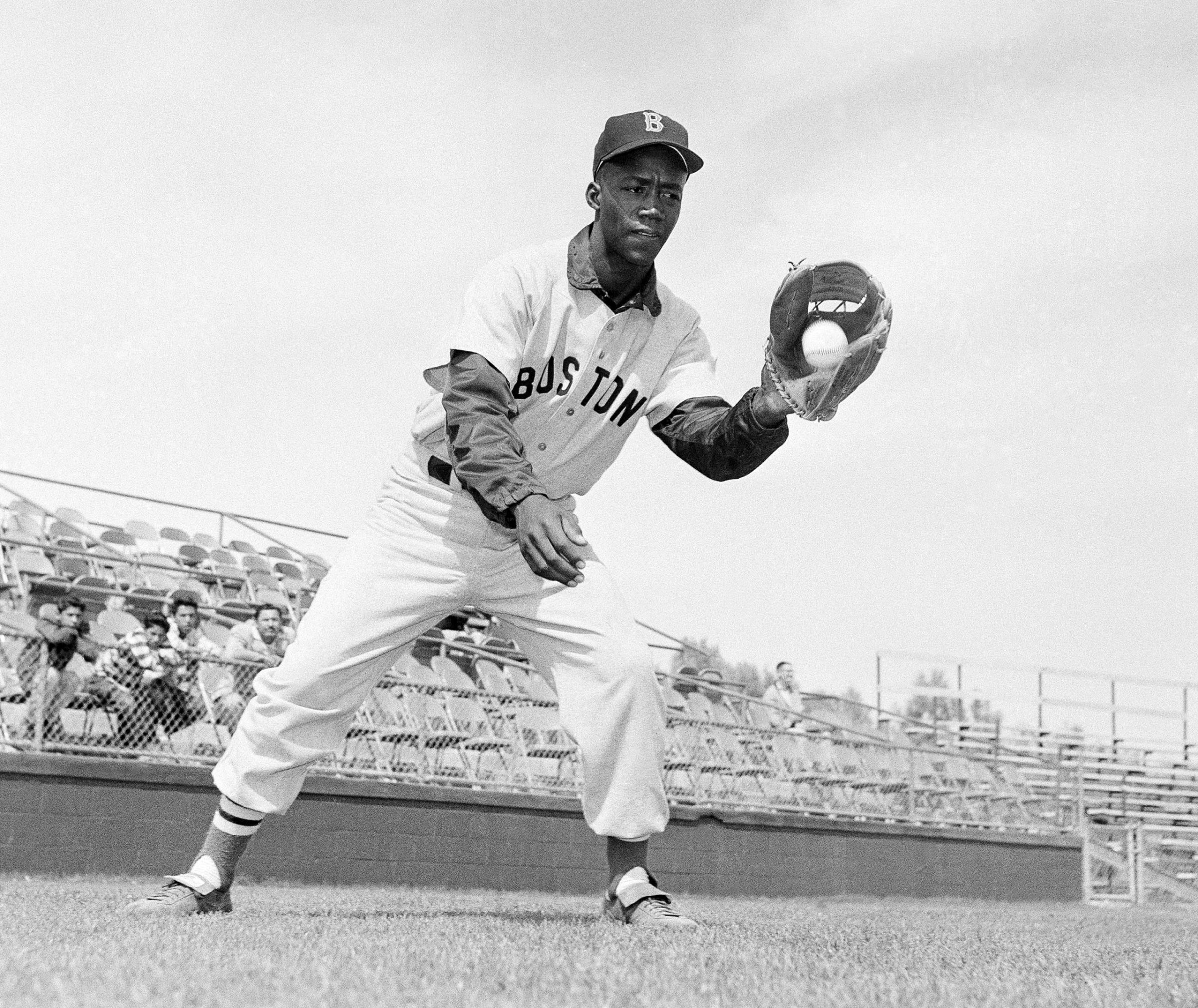

One distinction of Red Sox history that will never change, no matter how many generations pass, is that Boston was the last team in Major League Baseball to integrate. More than a decade after Jackie Robinson first broke major league baseball’s color barrier in 1947, the Red Sox called up shortstop Elijah “Pumpsie” Green.

Green, who would later say that coaches on the team would freely use racial slurs in his presence, performed well during spring training in 1959. (He had been signed in 1953 but had stayed in the minors for his first few years.) But, as his hitting showed some signs of weakness as April neared, the Red Sox sent him back down to the minors. The NAACP called for an investigation into the team’s business practices. That April, TIME explained that the Sox would have to “plead to the Massachusetts Commission Against Discrimination that Green needs more seasoning in the minors” — they’d have to prove, in other words, that he’d been sent down because of his ability, not his race.

As these events progressed, none other than Jackie Robinson himself made it clear what he thought.

Robinson had a personal stake in the question. He recalled at the time that he had been given a tryout with the Red Sox all the way back in 1945, two years before his debut with the Dodgers. As the Boston Globe later explained, progressive city politician Isadore Muchnick had told the team that if they didn’t let black players try out — even though MLB was not yet integrated — they risked losing some of the preferential treatment the city offered them. Robinson, already a veteran and a well-known athlete, was one of three players invited.

But the tryout that had been originally scheduled was cancelled with short notice, giving the players the sense that the team was avoiding them. Only after white newspapers began reporting that ballplayers waited in their hotel rooms to be called for their promised tryouts did the team rescheduled the event. Though people present that day attested that Robinson played extremely well — and the Red Sox, especially with the war still on, needed players — nothing came of it.

“We were told they never saw anybody do so well in a tryout, and that’s the last thing we were told…” Robinson recalled in April of 1959. “There’s no question that if the Red Sox wanted [a Negro player] they could find one.”

Though the Dodgers also dismissed Robinson in a similar fashion that same year (1945), the Red Sox incident stood out. “As a result of such duplicity, the African American community held the Red Sox in disdain more so than any other team in the game,” Glenn Stout wrote in a 2004 issue of the Massachusetts Historical Review. Robinson also made sure that the Red Sox episode was not forgotten. He “tweaked the team on the issue at every opportunity,” as Stout put it.

Meanwhile, the Red Sox prevailed in the discrimination hearing about Green. But just a few weeks later, in July of 1959, Boston called him up. He played in his first big-league Red Sox game on July 21. Green went on to play five seasons, all but one for Boston.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com