Resilience has been the cornerstone of Lincoln Heights since its inception 70 years ago. The Cincinnati suburb was the first African-American self-governing community north of the Mason-Dixon line. Cheap plots of land offered an opportunity for black people traveling north in search of a better life. But after a promising start, the village quickly fell into disrepair. Institutional racism, poor infrastructure and a dire lack of money all contributed to its gradual decay.

Photographer Inzajeano Latif quickly identified with the town. Hailing from Tottenham, north London, Latif noted many similarities between this neighborhood and his back home. After reading about Lincoln’s history, he began to see his ten-year project on the English suburb as part of a wider picture. “I started thinking: ‘Why it is that areas where mostly ethnic minorities live, there’s always some kind of struggle?’” Latif tells TIME. “There’s high rate of unemployment, there are high crime rates.” This reflection gave focus to his work in Tottenham and called him to travel to Ohio where he deeply embedded himself within the community; taking photographs and recording short interviews.

Latif has always been drawn to documenting the fringes of society. “[Growing up], Tottenham was a dump,” he says. “And it really affects your psyche and your day-to-day way of life.” He felt it was vital to connect the dots and understand that living in a state of poverty was a global phenomenon, by no means resigned to the third world.

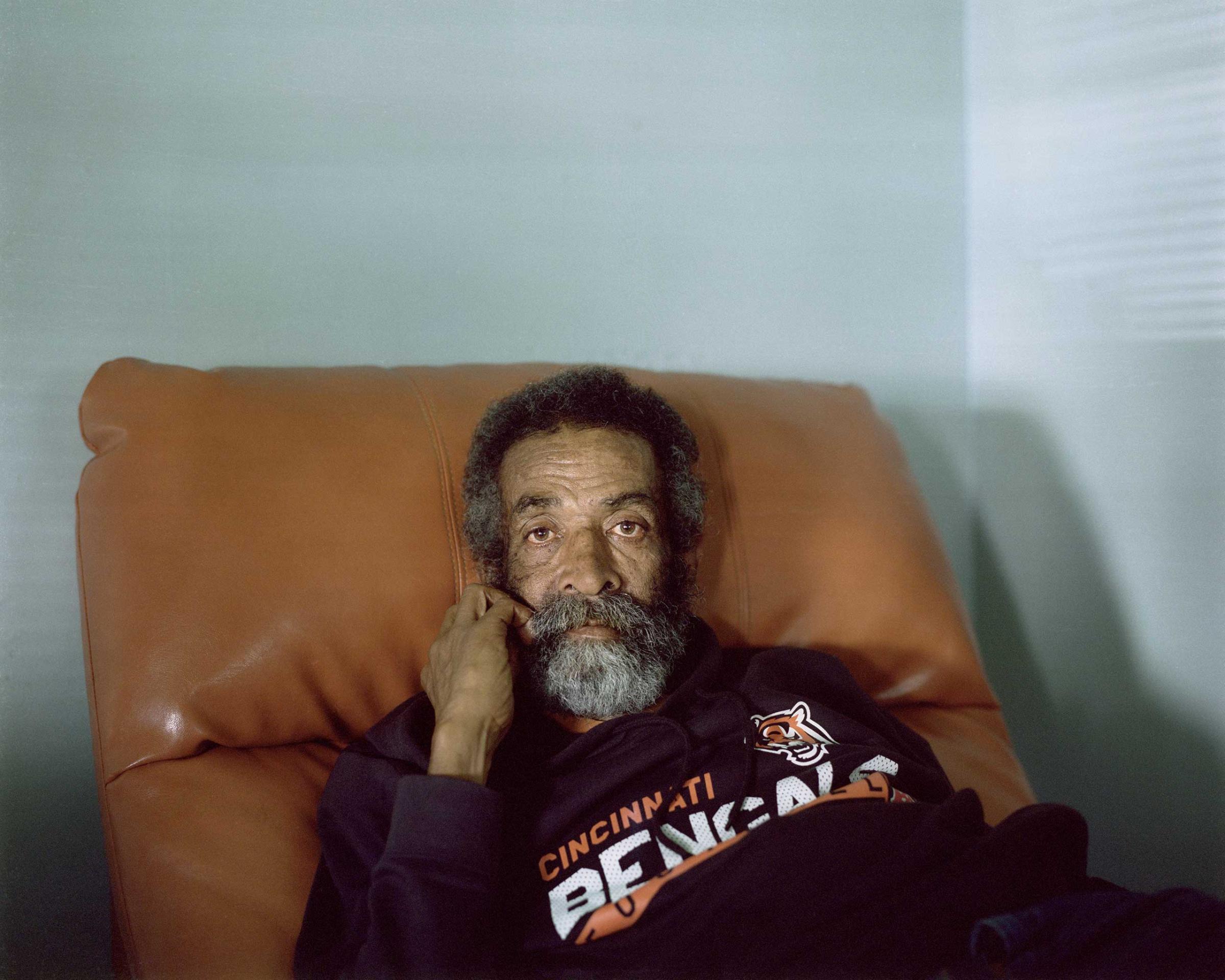

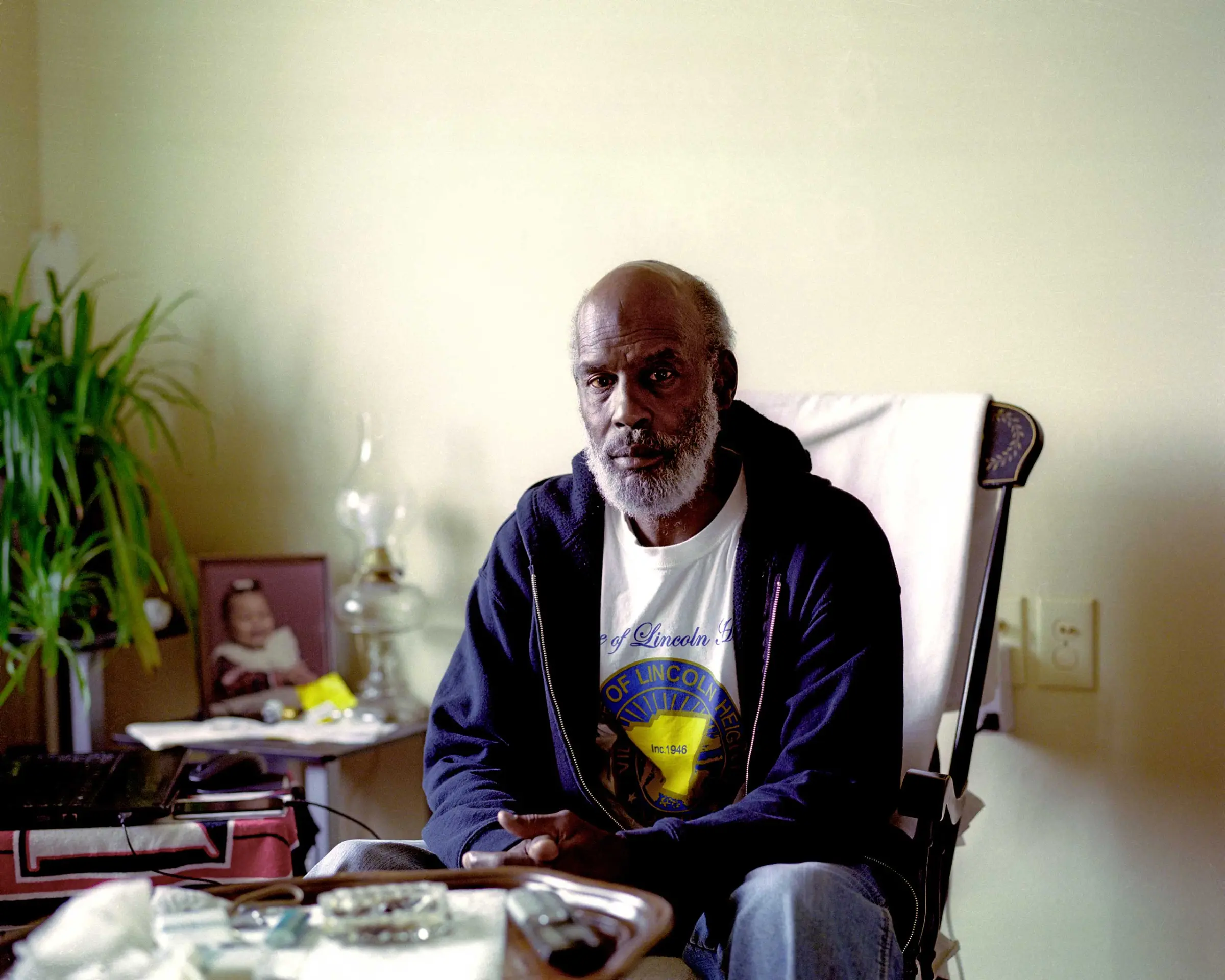

According to demographic data site Cubit, the median household income in Lincoln Heights in 2o15 was $23,662, with 39.0% living in poverty. “It’s 2017 and people are still having to live in the greatest civilization on Earth in complete squalor, in hardship,” adds Latif. Lincoln’s journey of small victories and big setbacks is keenly felt by the older generation. “I learnt how they still hold onto these really amazing values,” says Latif. “They place family and community at the heart of daily life. They try and help each other. I would like to think that the USA was built on these values in some way.” Latif’s gentle, piercingly honest portraits reveal the people’s endurance. The men and women he photographed in their 80s and 90s, still “hold onto this amazing hope that they will be able to achieve what they have wanted, that they will be able to live their dream.”

The senior citizens, who Latif calls the “foundations of Lincoln Heights”, are in some ways, the town’s last hope. Their fearless positivity has not been inherited by the younger generation; there is a distinct disparity between the old and the young, who have never known prosperity. “The younger generation seems to be completely disconnected with its history and what they can do to rebuild their neighborhood for their children someday,” says Latif. “In a sense, I partially see the dream fading away into a nightmare.” Latif cites an article by the Atlantic, which scrutinizes Lincoln’s history and lays bare the persistent roadblocks that have hampered progress.

The adolescent’s lack of despair is not without foundations. “They’re obviously going through their lives in a way that represents life for many young people in the western world these days,” says Latif. “You’ve only got to look at the stats on how hard it is for ethnic minorities to get work.” Latif thinks that if the young could sit with the old and understand the value of their heritage, their reality would seem less desperate. “You look at the Civil Rights Movement and the hard work that’s been done so far, there’s obviously still a lot more work that needs to be done,” says Latif. “And it’s up to these younger people to take the helm as it were and look to the past.”

But it isn’t as simple as that. There are fateful factors outside their control that prevent this society from really progressing. Institutional racism, lack of jobs, lack of infrastructure and hostility from neighboring communities are all major roadblocks that have been present from the start. But it’s lack of money that is the most polluting. “It really is a town that is fading away,” Latif says. “There’s some major funding going into the motorway that runs along the outskirts. There’ll be a big sign for Evendale, a nearby neighborhood, but there won’t be any sign to say Lincoln Heights. Because they can’t afford to invest any money.” Instances like this are a painful reminder of the village’s struggle for dignity and recognition.

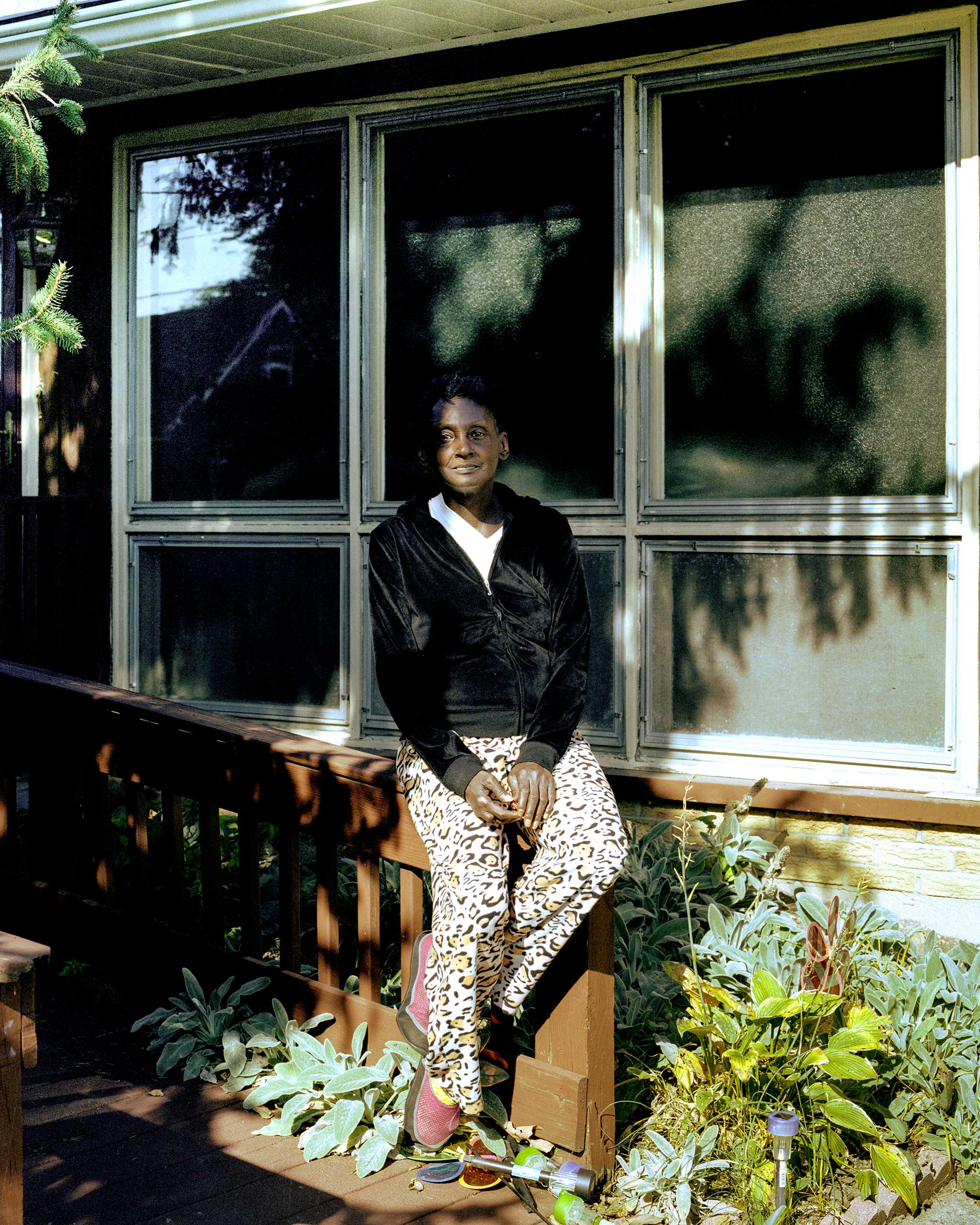

Latif’s series riffs on poverty and deterioration, but the overarching feeling is still positive. In one portrait, a woman named Cynthia is framed by curtains in her window; she is contextualized by her home and her situation. But the reflection of the trees on the glass serve to transcend the every day; she is brought alive by the natural serenity of the leaves and the sky. “There are signs of despair; that’s just how it is,” says Latif. “But the overlying work is about hope and resilience.”

Inzajeano Latif is a British documentary and portrait photographer, currently based in the USA. You can view more of his work here. Follow him on Instagram.

Myles Little, who edited this photo essay, is a Senior Photo Editor at TIME.

Alexandra Genova is a writer and contributor for TIME LightBox. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram

Follow TIME LightBox on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com