It was nearly 70 years ago that the National Mental Health Association first observed May as Mental Health Month, a designation meant to raise awareness about mental-health issues. But a lot has changed since then in the American conversation about these problems.

One of the biggest steps was the move away from a model in which patients with serious mental-health problems were expected to live in large, typically state-run institutions. As TIME explained in 1975, the population in such institutions had been more than halved between the late 1950s and the early 1970s. Much credit for the drop was due to the development of new drugs that made it possible for outpatient treatment to be effective––and to rising costs that made such treatment more appealing. But another important factor was the growing belief that life spent entirely within a hospital’s walls was actively harmful for the patients it aimed to treat.

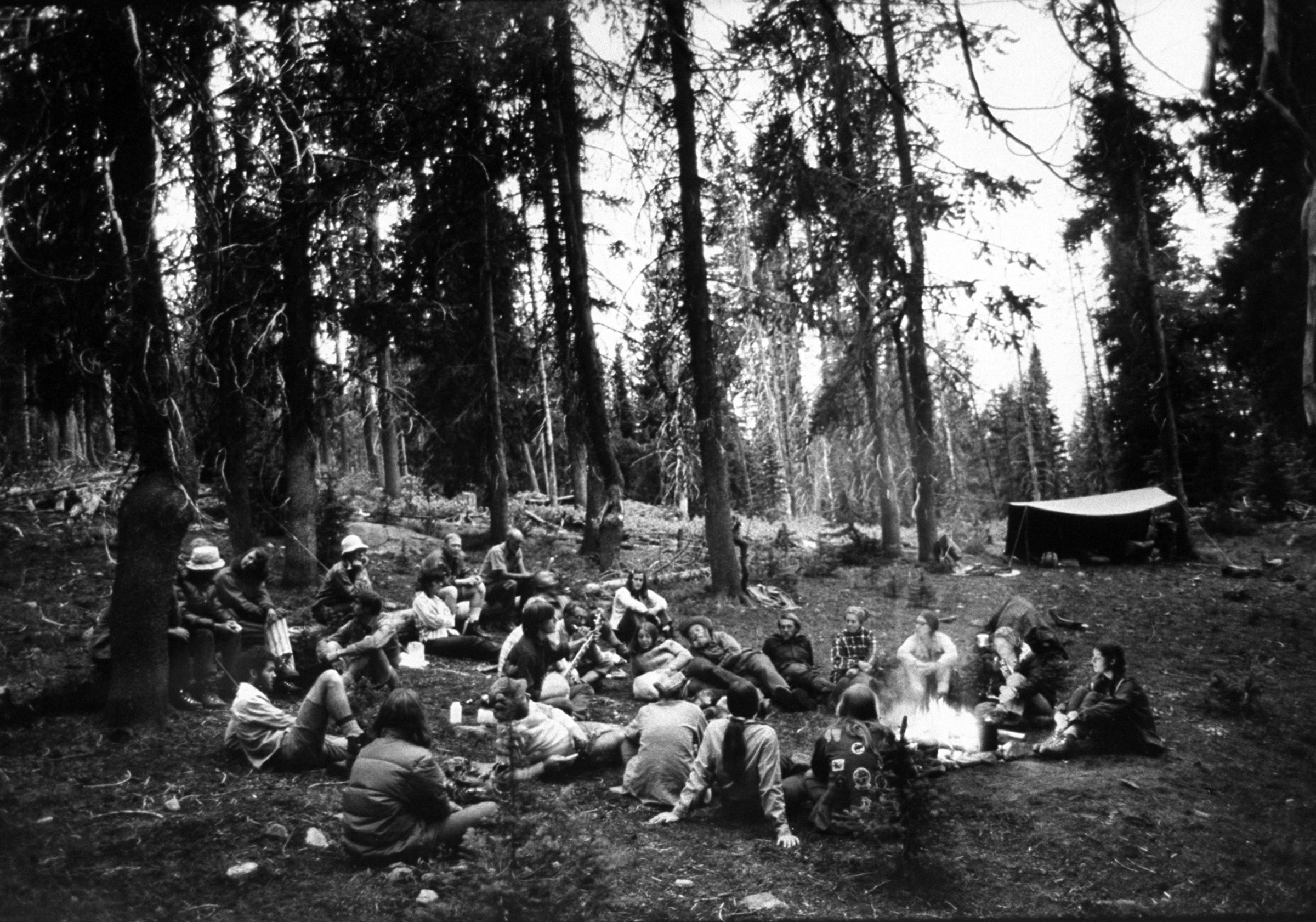

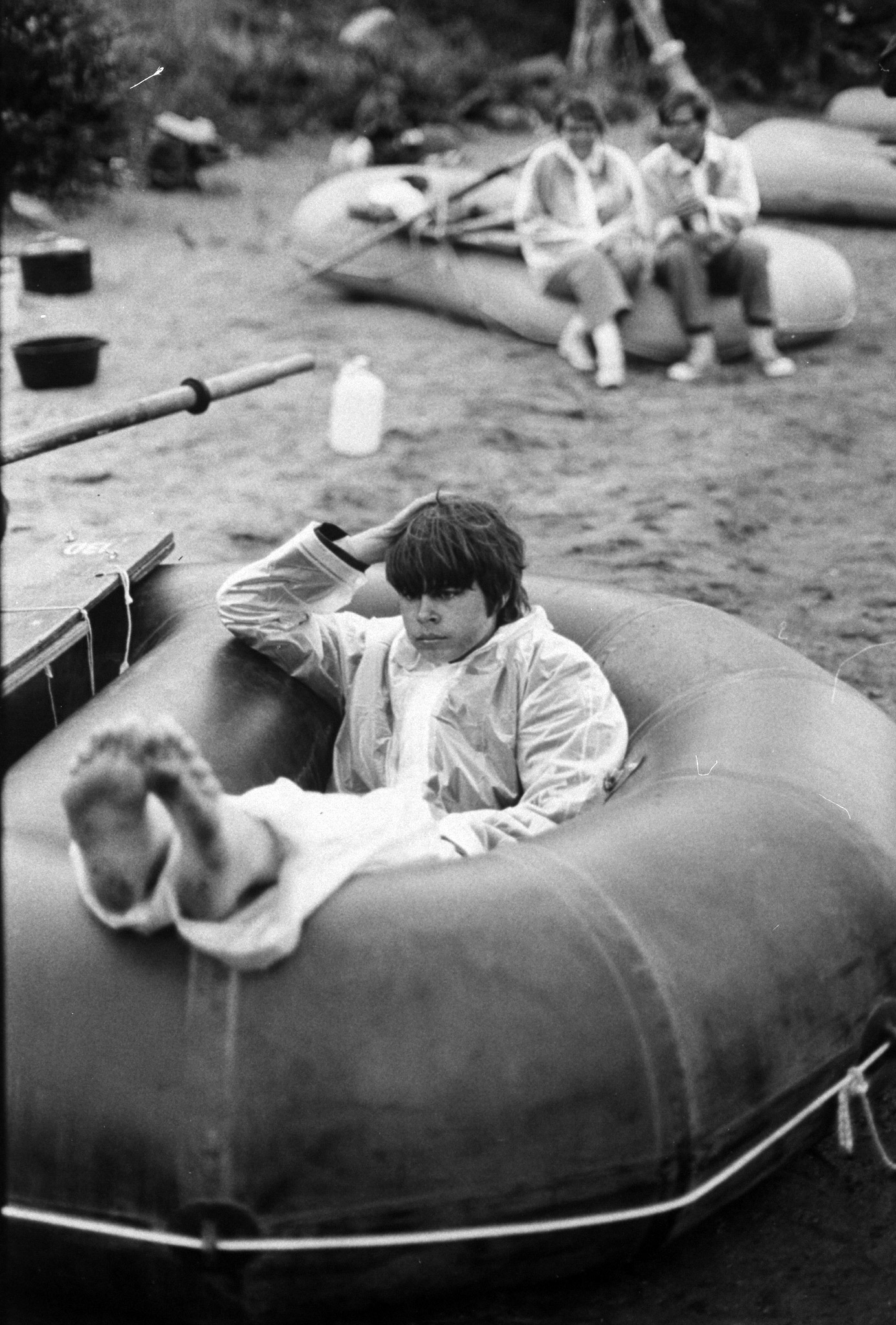

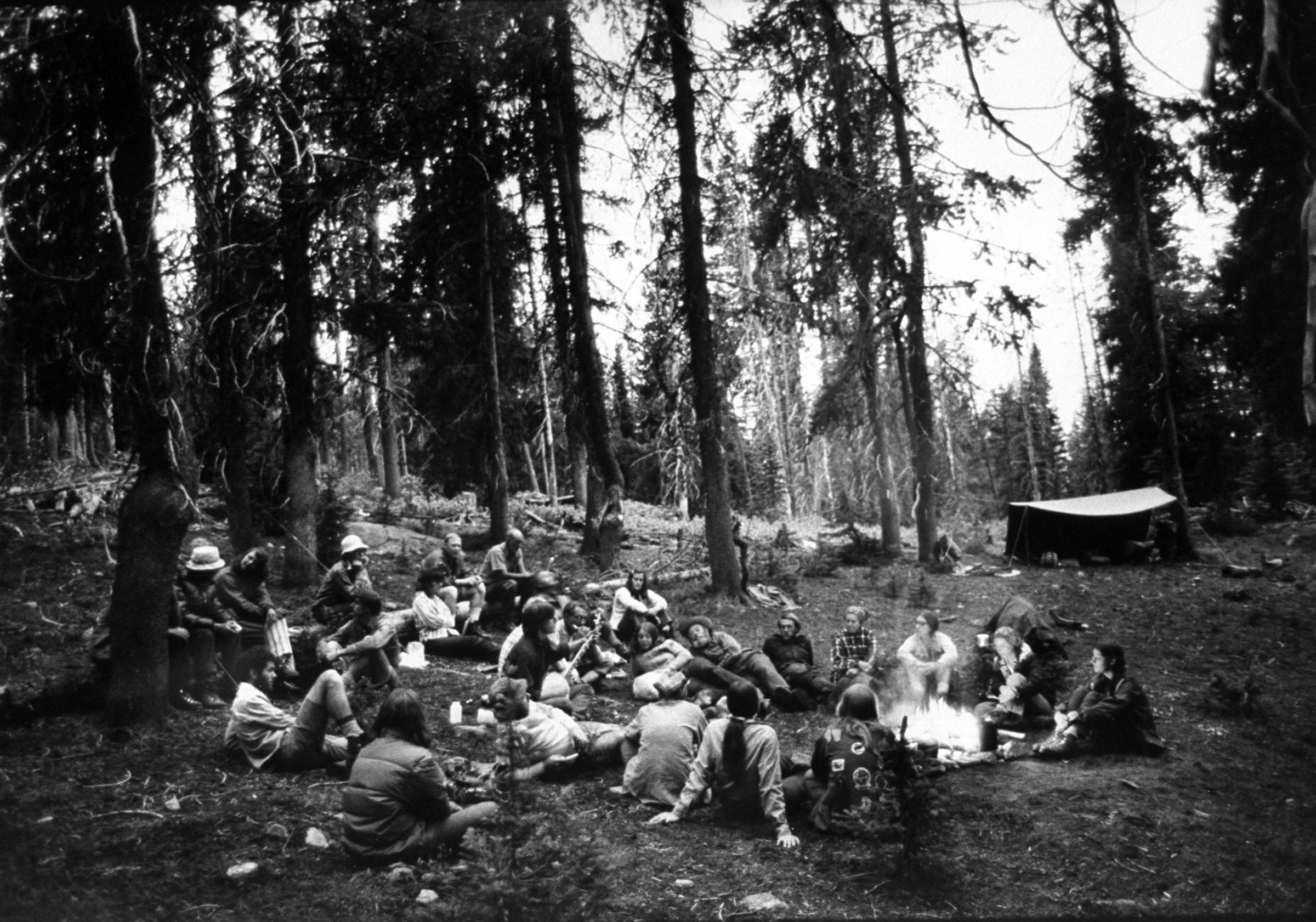

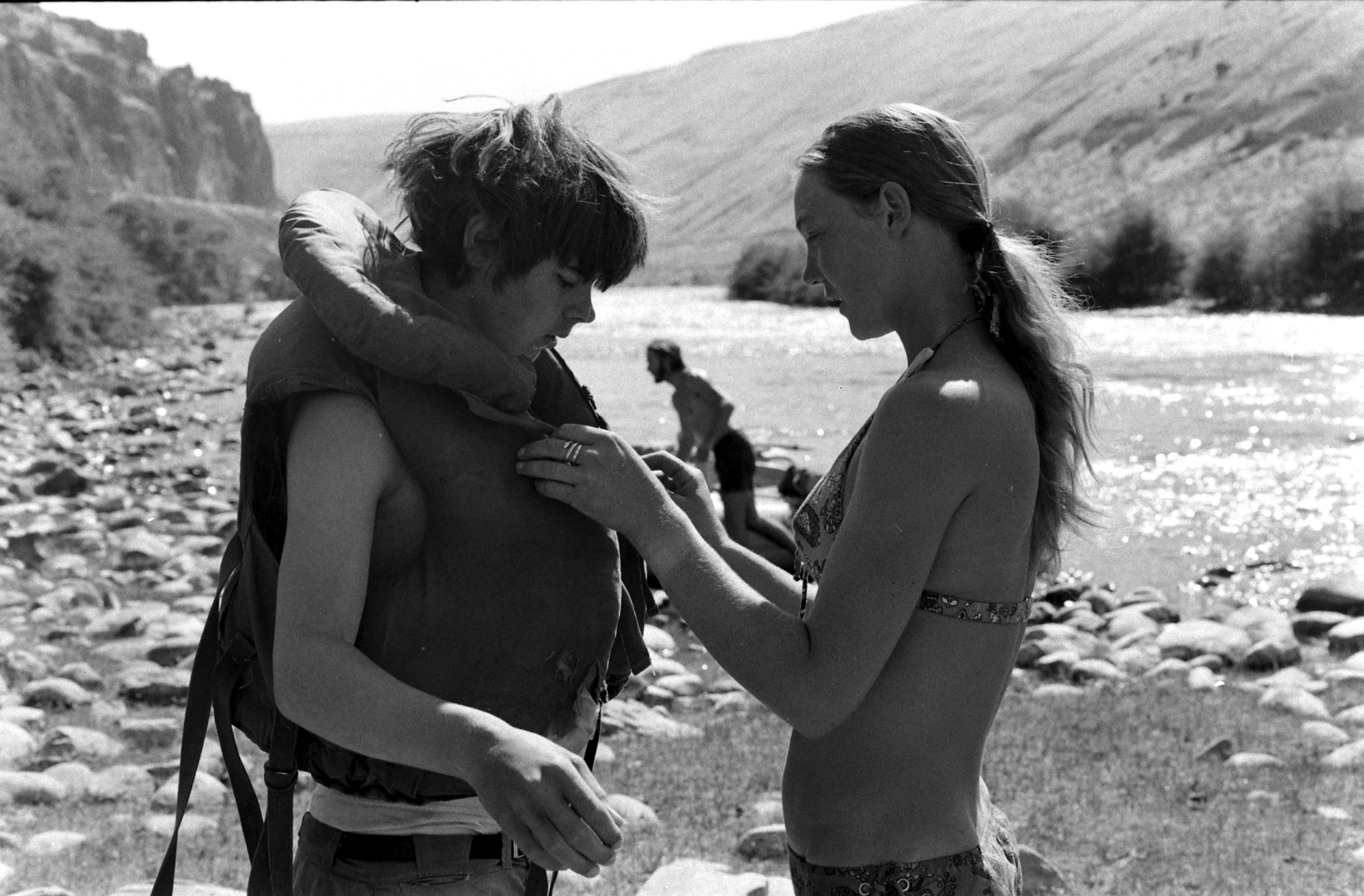

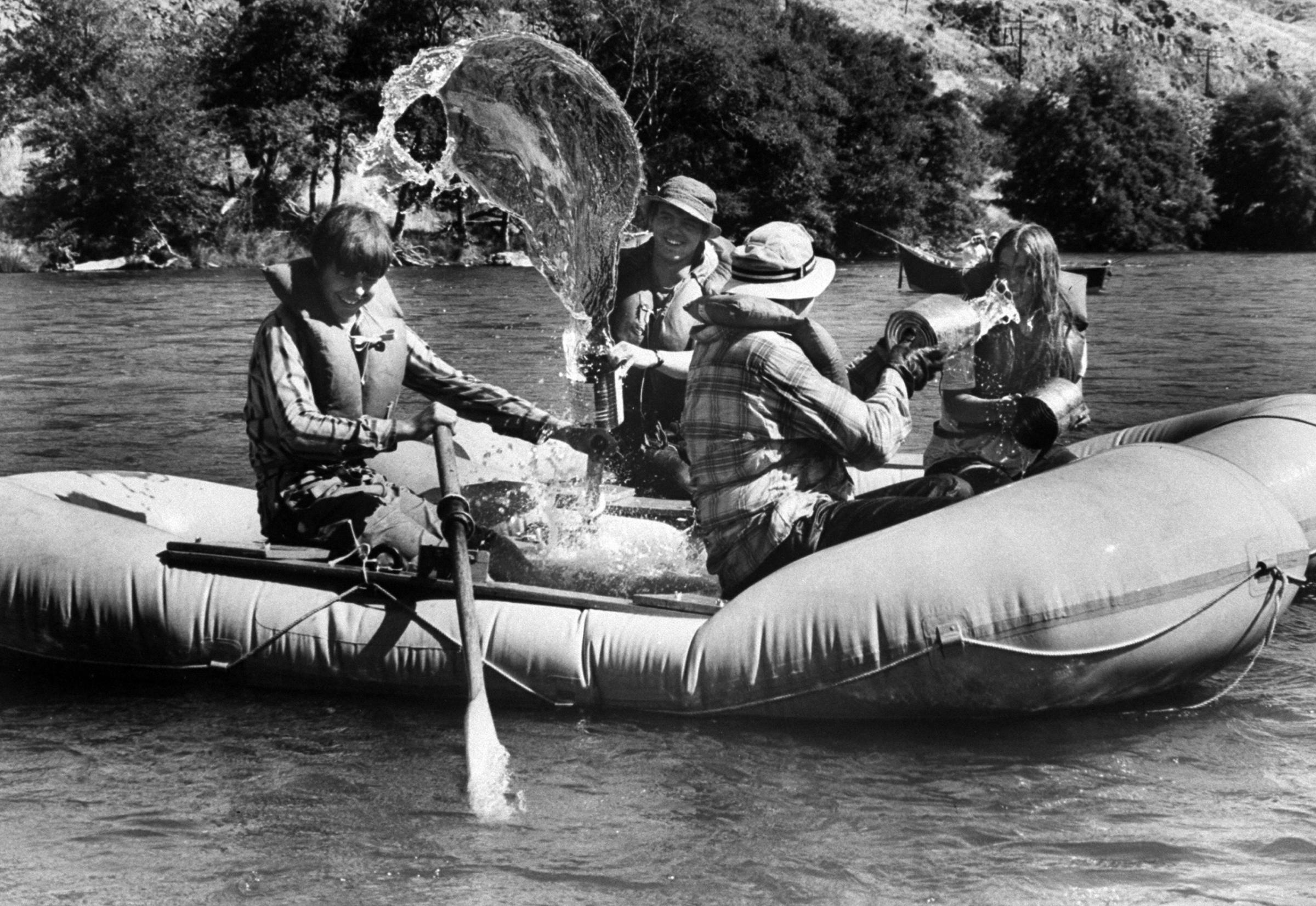

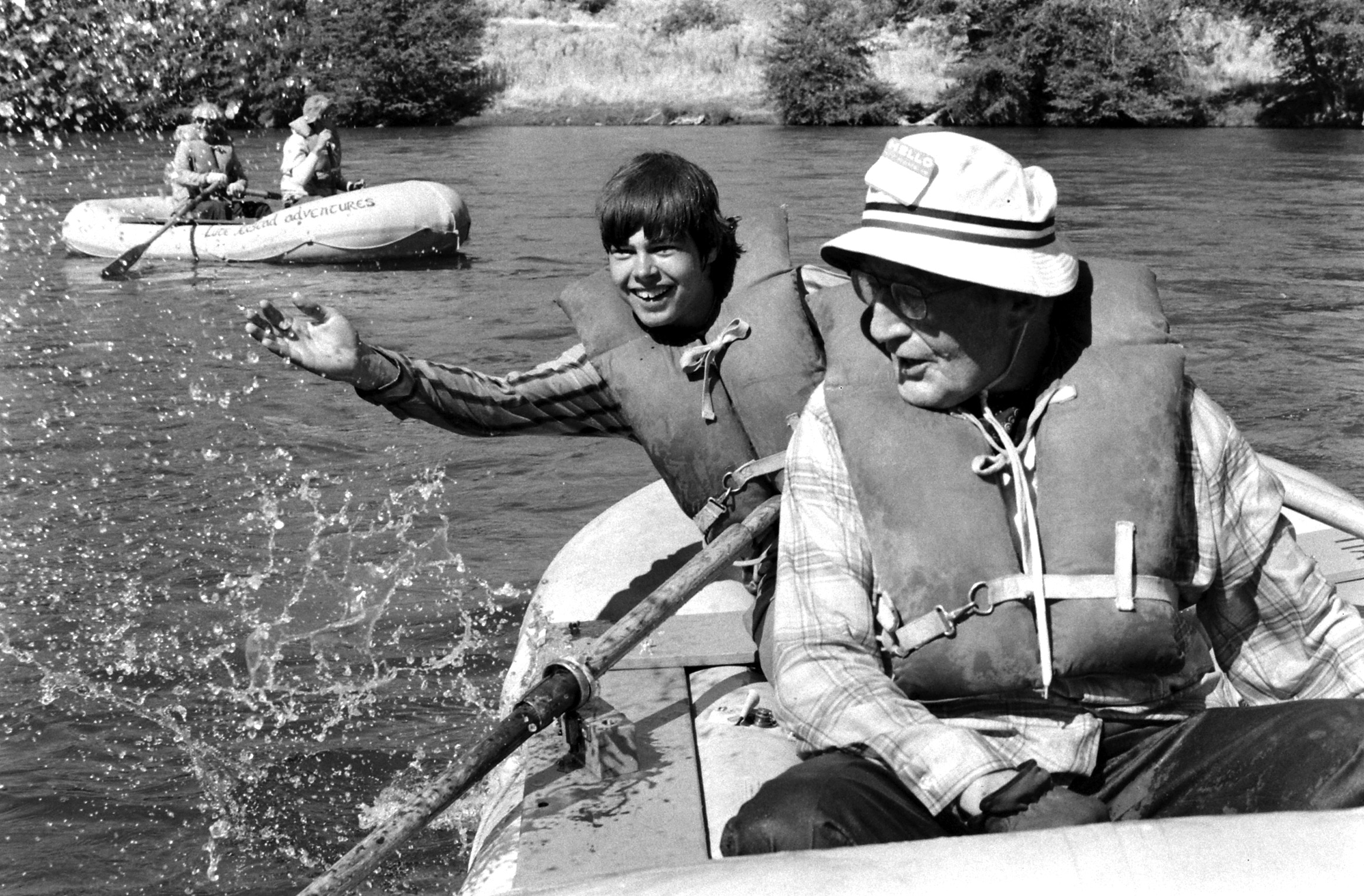

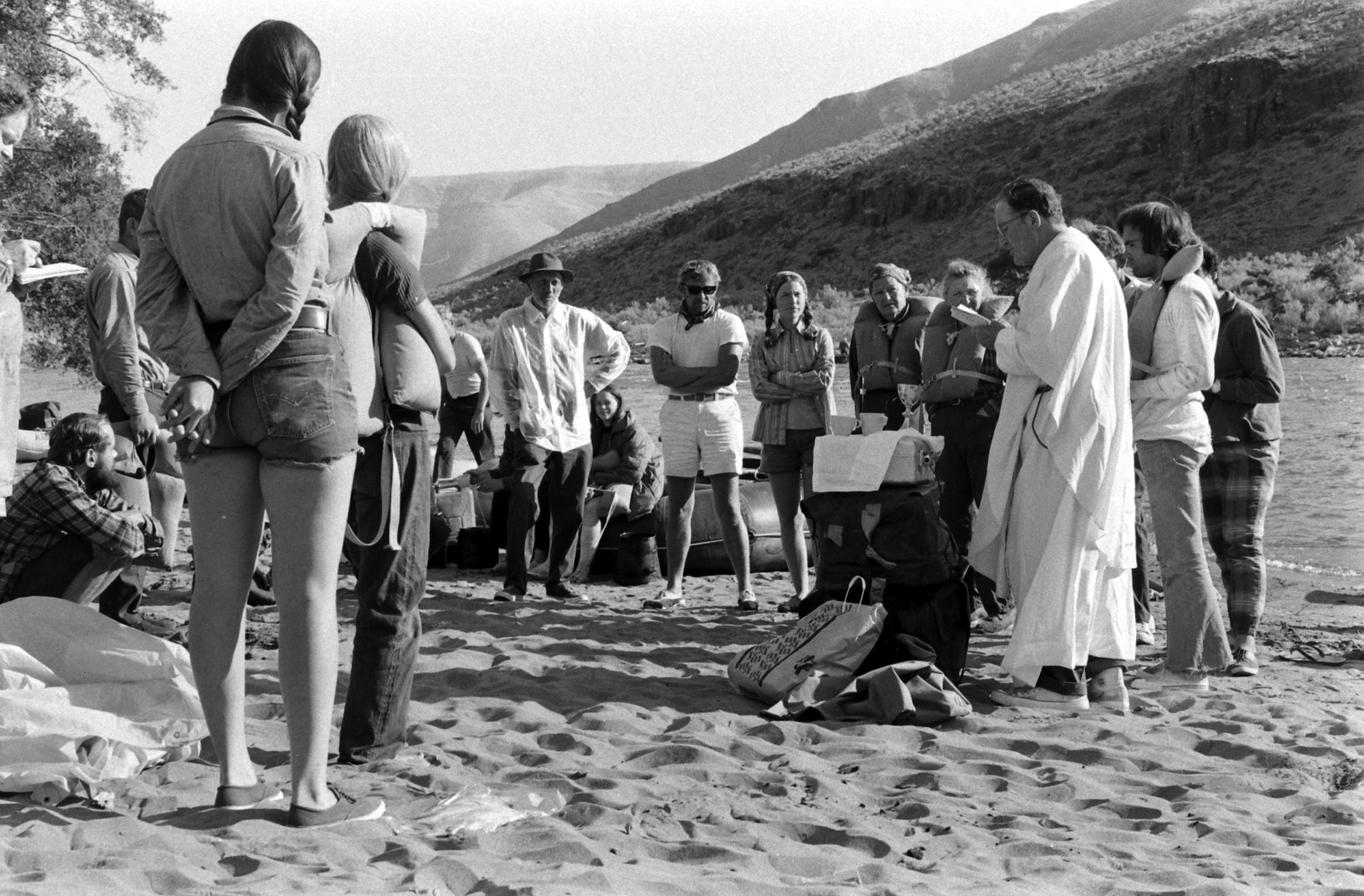

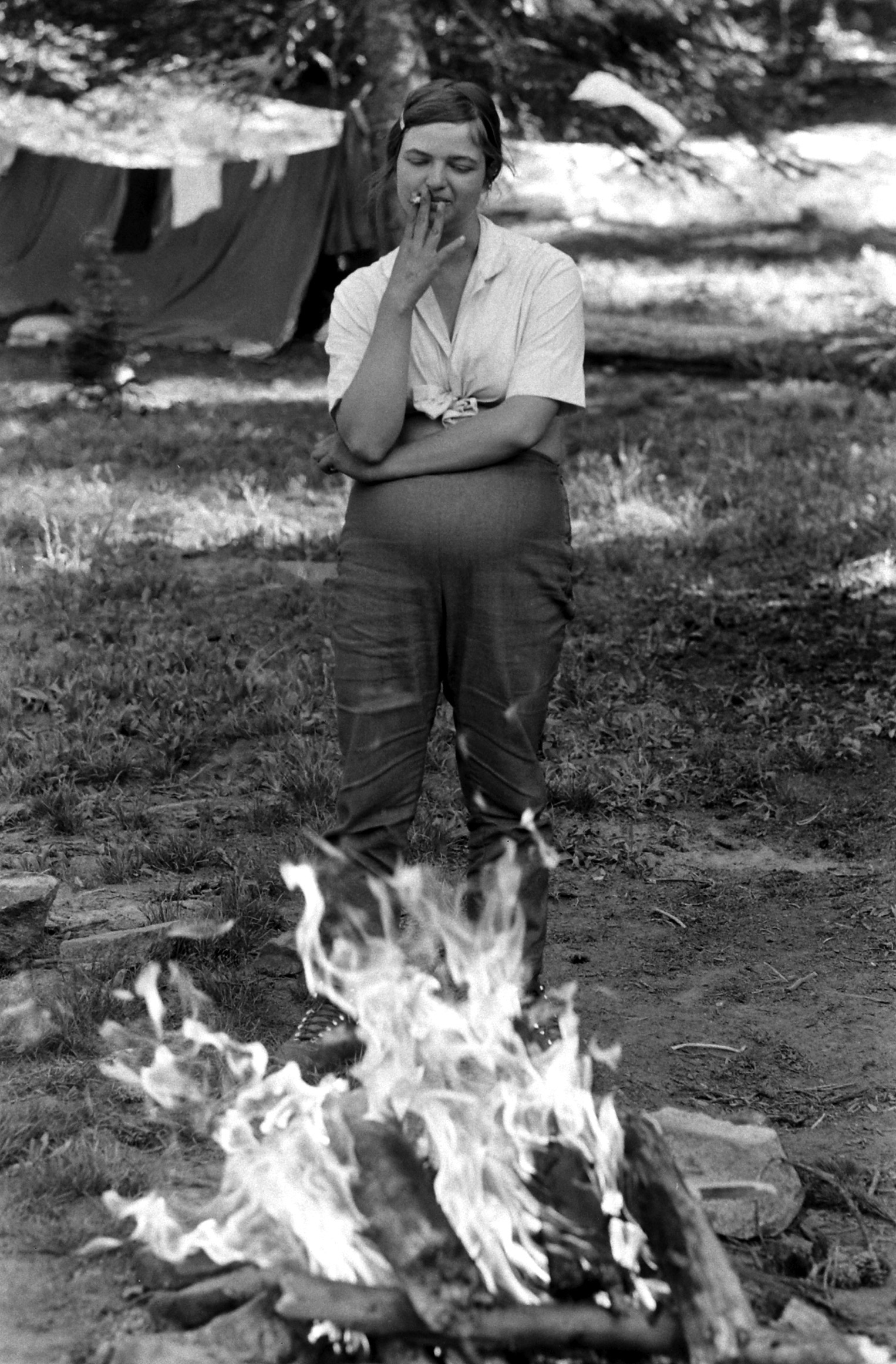

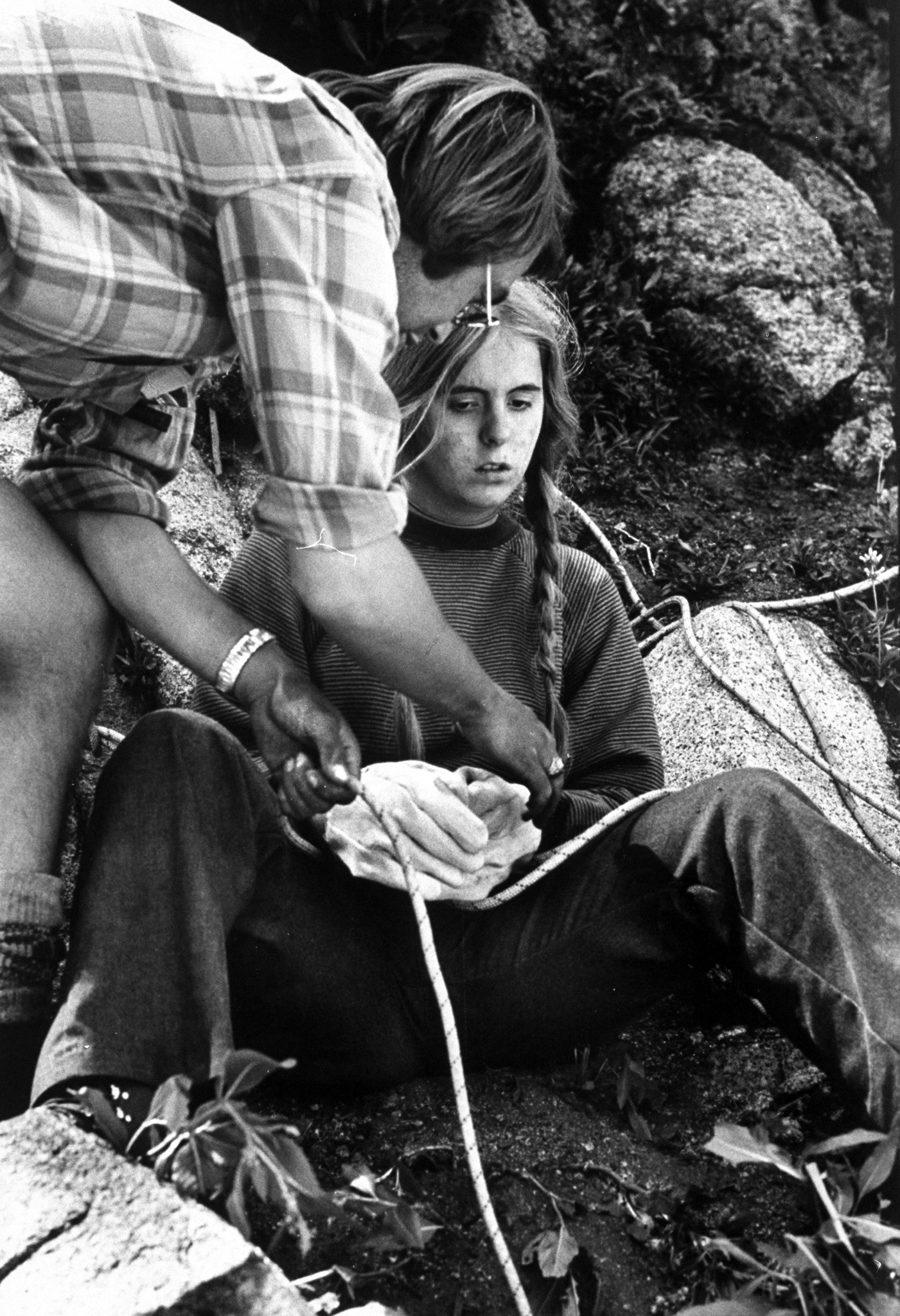

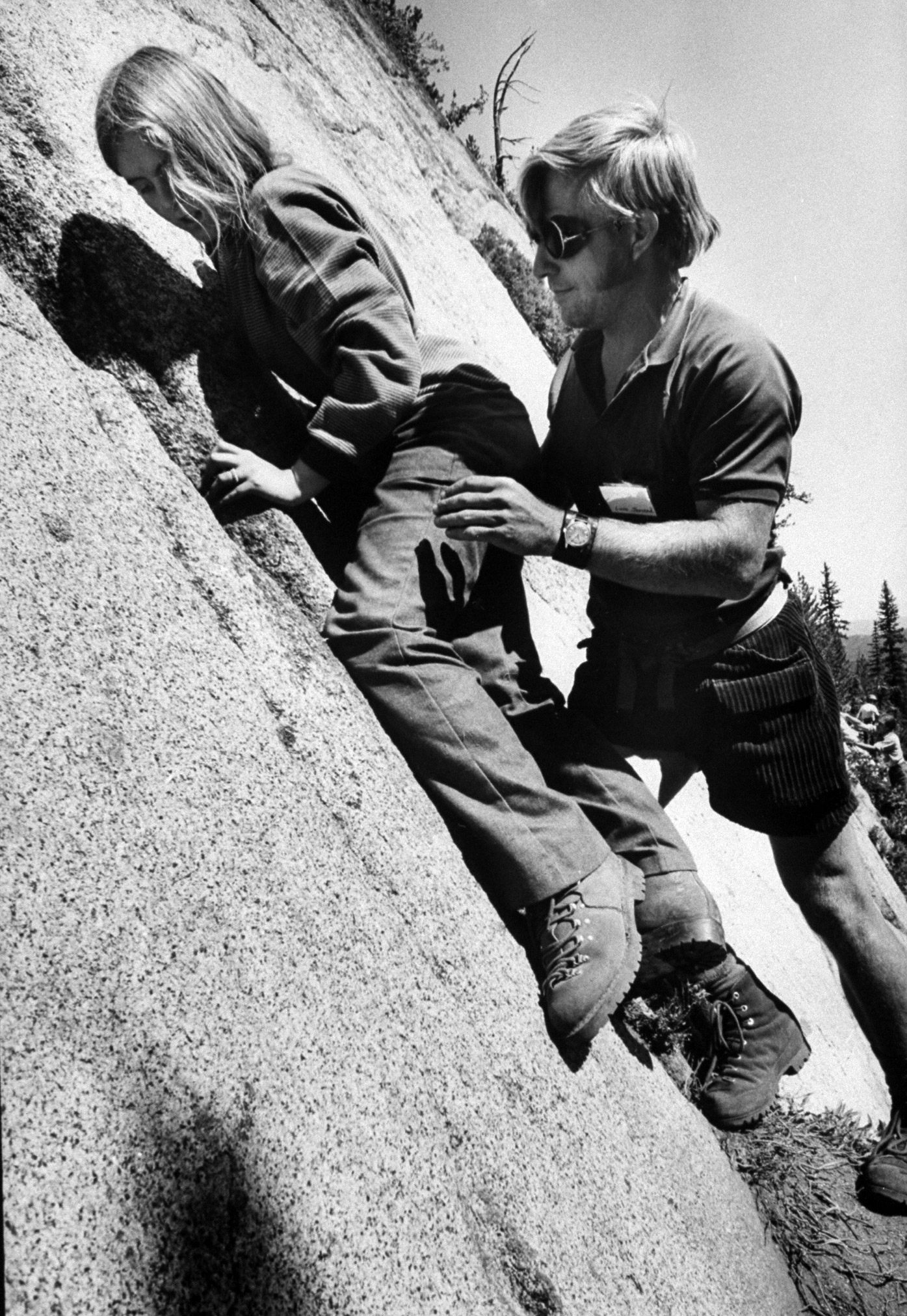

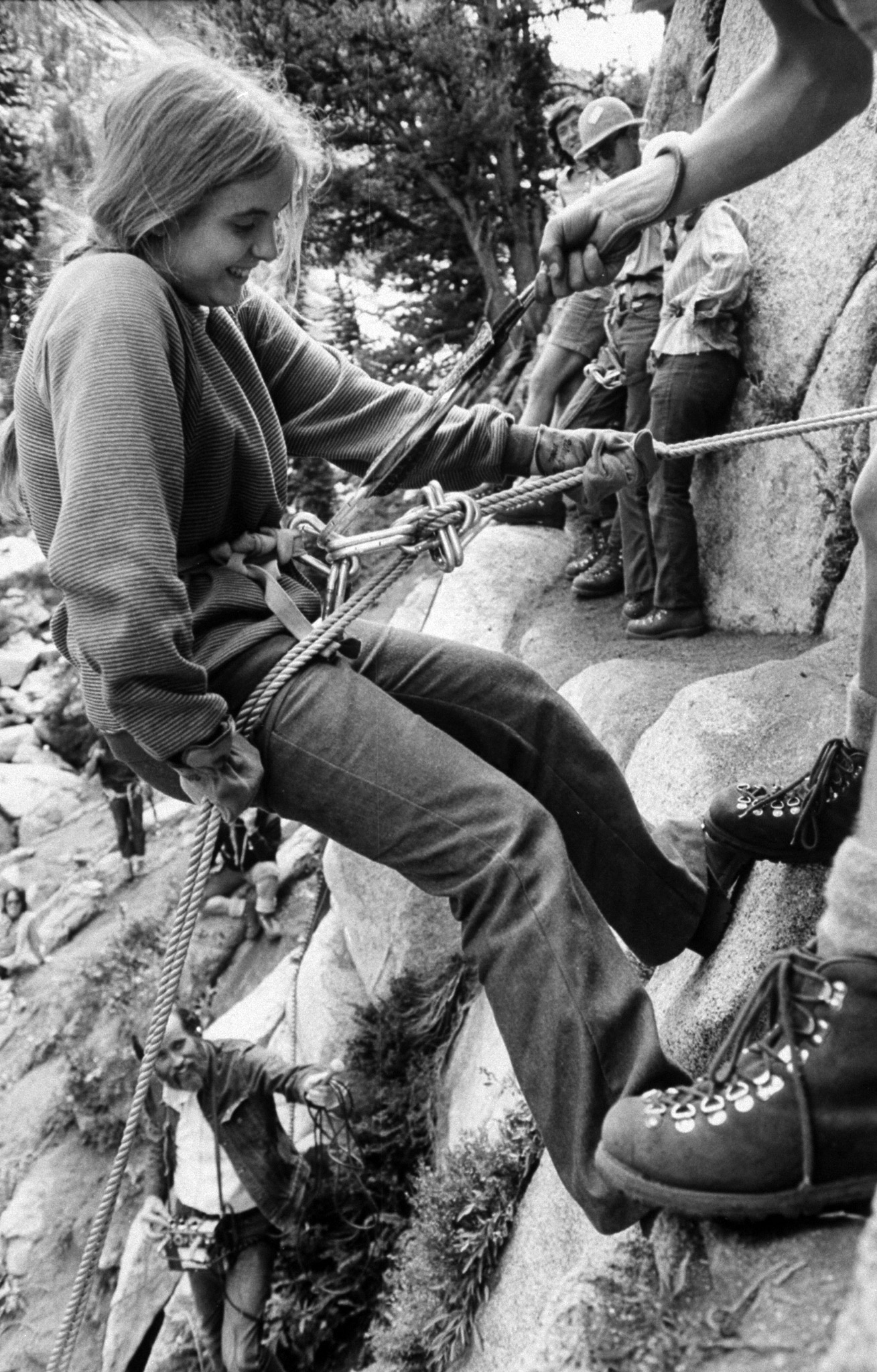

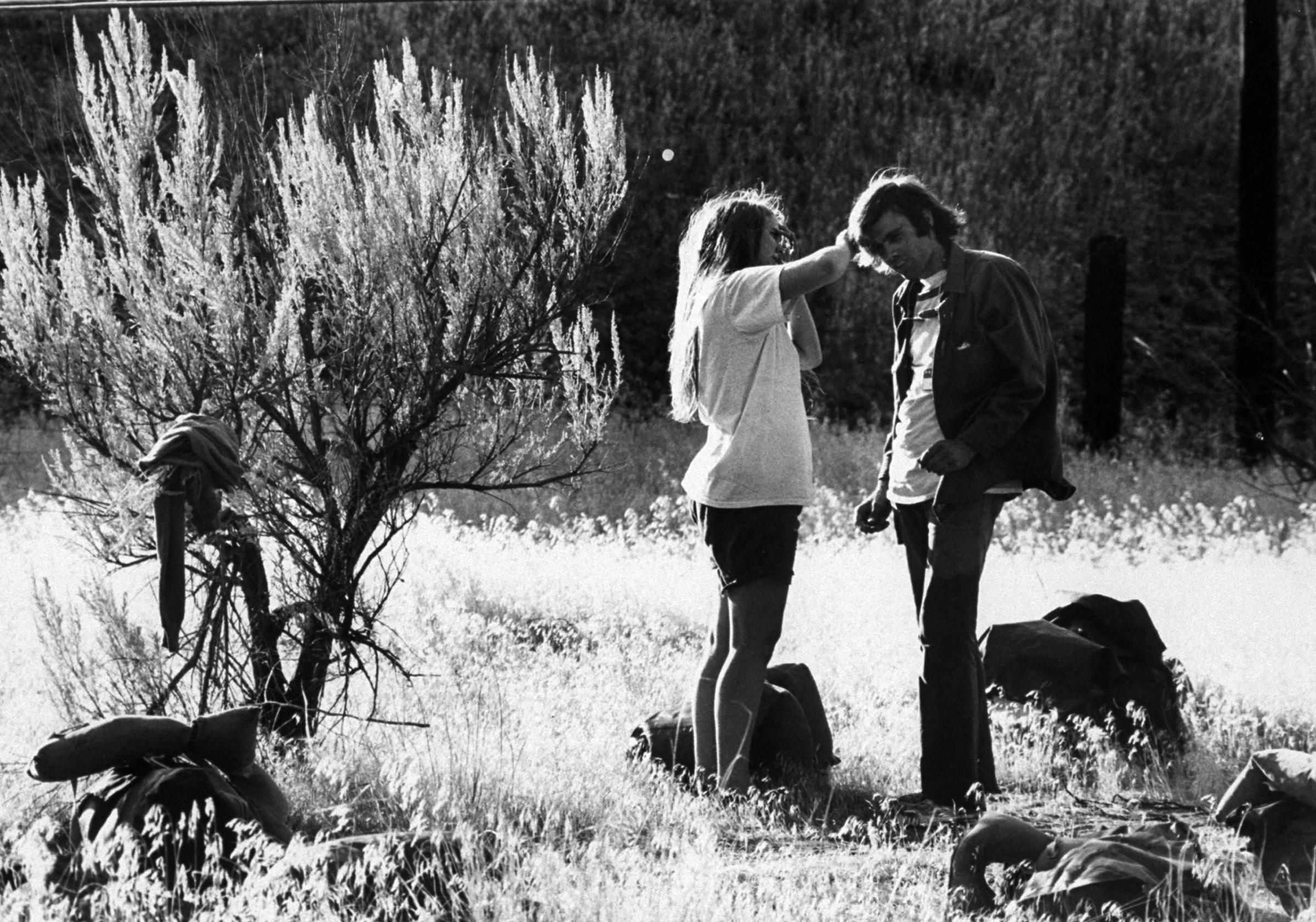

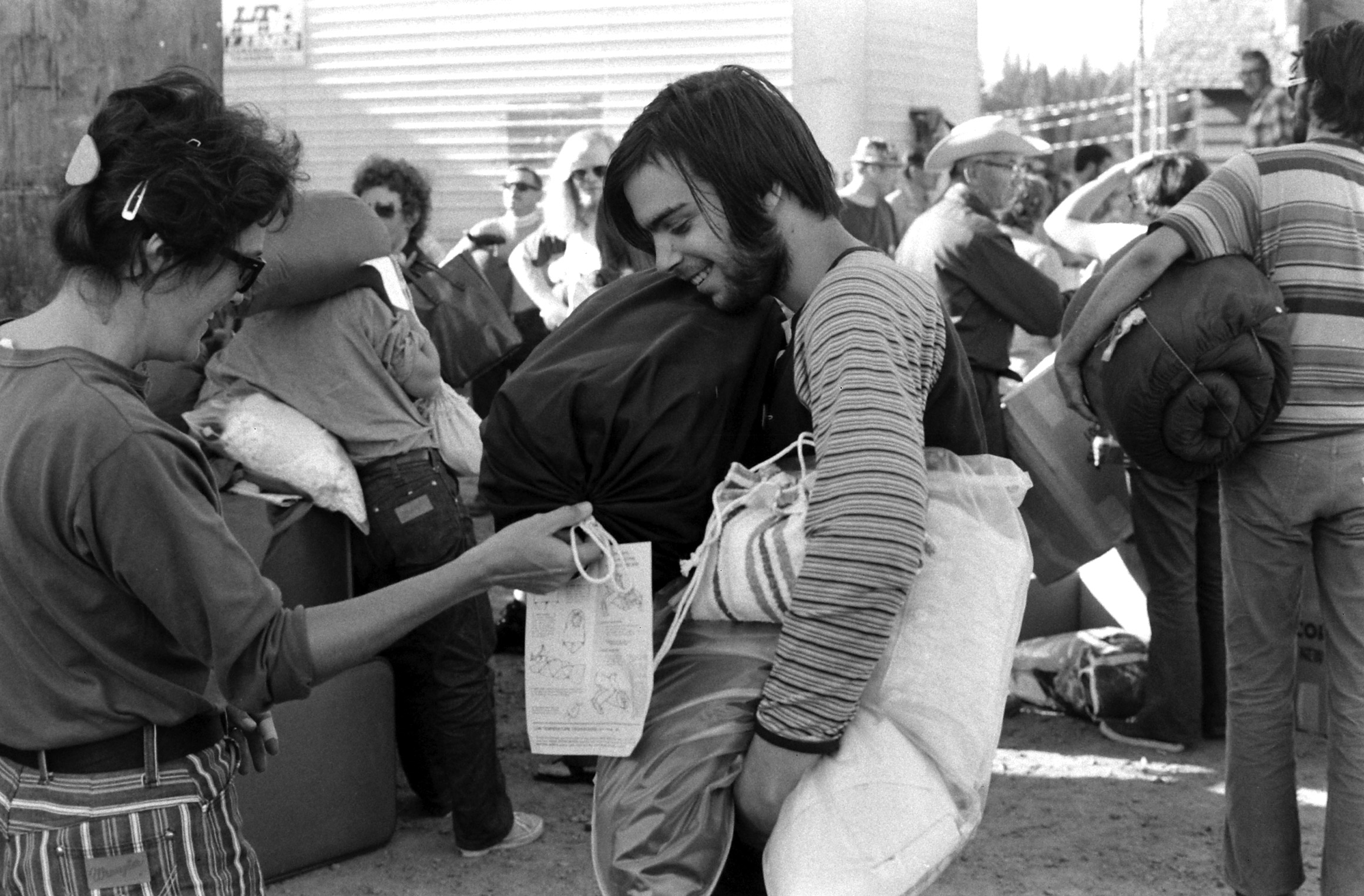

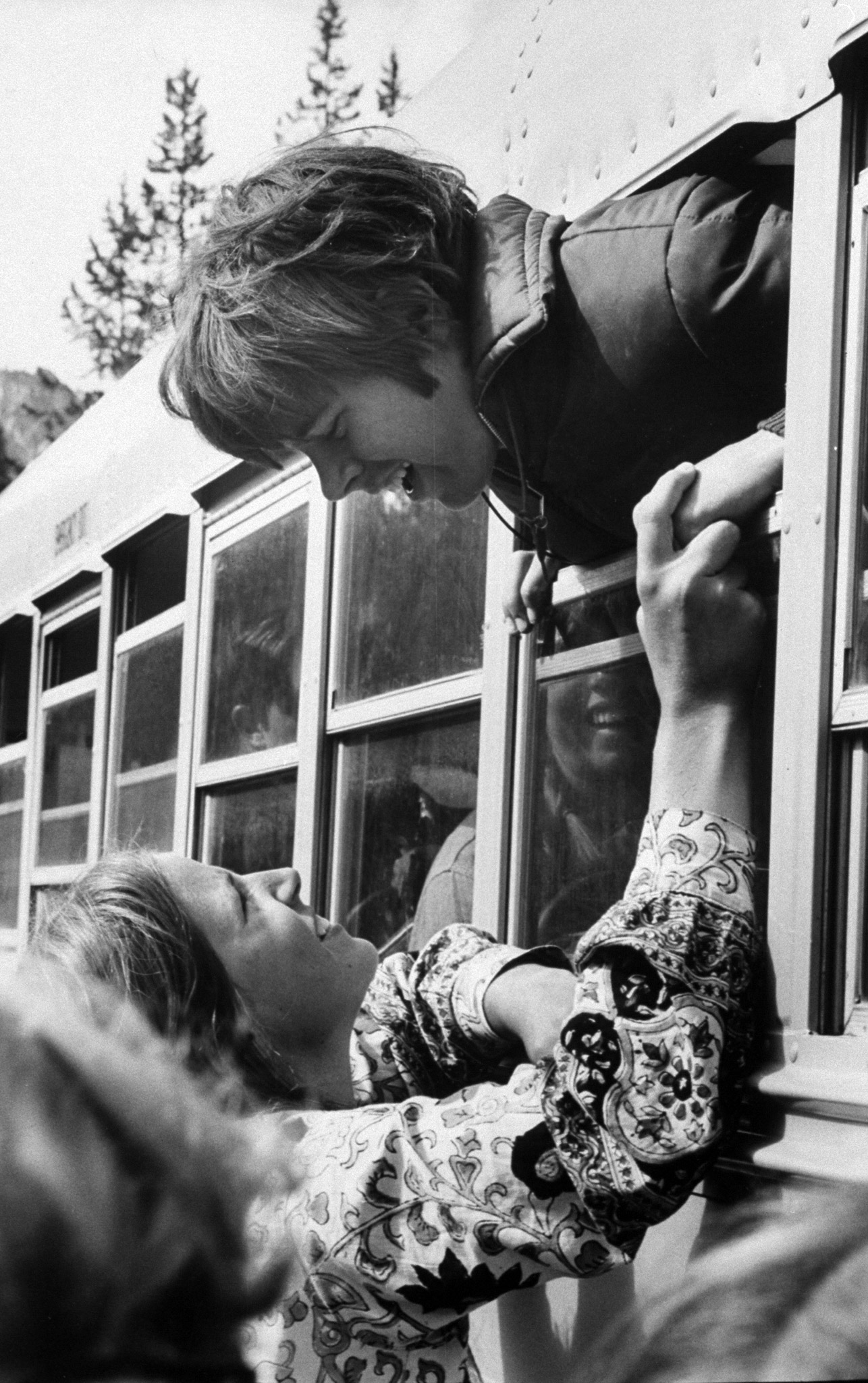

In 1972, that belief was on display in the pages of LIFE magazine, which sent photographer Bill Eppridge and correspondent John Frook to Anthony Lake, Ore. There, 51 of the most troubled patients at the Oregon State Hospital, including those with violent psychosis and those who had committed serious crimes under the influence of their diseases, were sent into the woods for more than two weeks, along with 51 staffers and a host of guides.

The experiment was the brainchild of the hospital’s superintendent, Dr. Dean Brooks, and Everest climber Lute Jerstad. They wondered, as Frook put it in his notes on the assignment, which were preserved in LIFE’s archives, what would happen when you took those patients “away from strict security” and put them somewhere “that had no perimeter” among “the rest of us who have not yet been certified as crazy.”

The takeaway, per Frook: “Well, it worked.”

One young woman became more comfortable with herself and thus easier for others to be around. One boy never talked much but began to smile more. A woman who had had to be physically carried for an early portion of the trip became a star camper when it turned out she could actually make a good meal out of the available supplies. Though many signs of institutionalized life carried over — used to sleeping and waking on a regular schedule, some patients would at first fall asleep at the prescribed time wherever they happened to be — many of the campers blossomed in the new environment. As LIFE reported in the version of the story that ran in print, 14 of the patients who participated in the experiment were eventually released from the hospital. Though Dr. Brooks credited outpatient counseling and drug therapy with their ability to cope in the world outside, he believed the camping trip could be given credit for lending them the courage they would need to make that change.

And the assignment, which generated a whopping 90-odd contact sheets worth of photographs, changed Frook too. As he told managing editor Ralph Graves, he had started the assignment wary of camping out, away from civilization, with people who had violent histories. But the “forced interdependence” of the trip soon changed that. Not only did he find that it was sometimes hard to tell who on the trip was a patient and who was staff, he also found that some of the very people of whom he’d once been afraid were “extraordinarily tender” to others and to him.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- How Elon Musk Became a Kingmaker

- The Power—And Limits—of Peer Support

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com