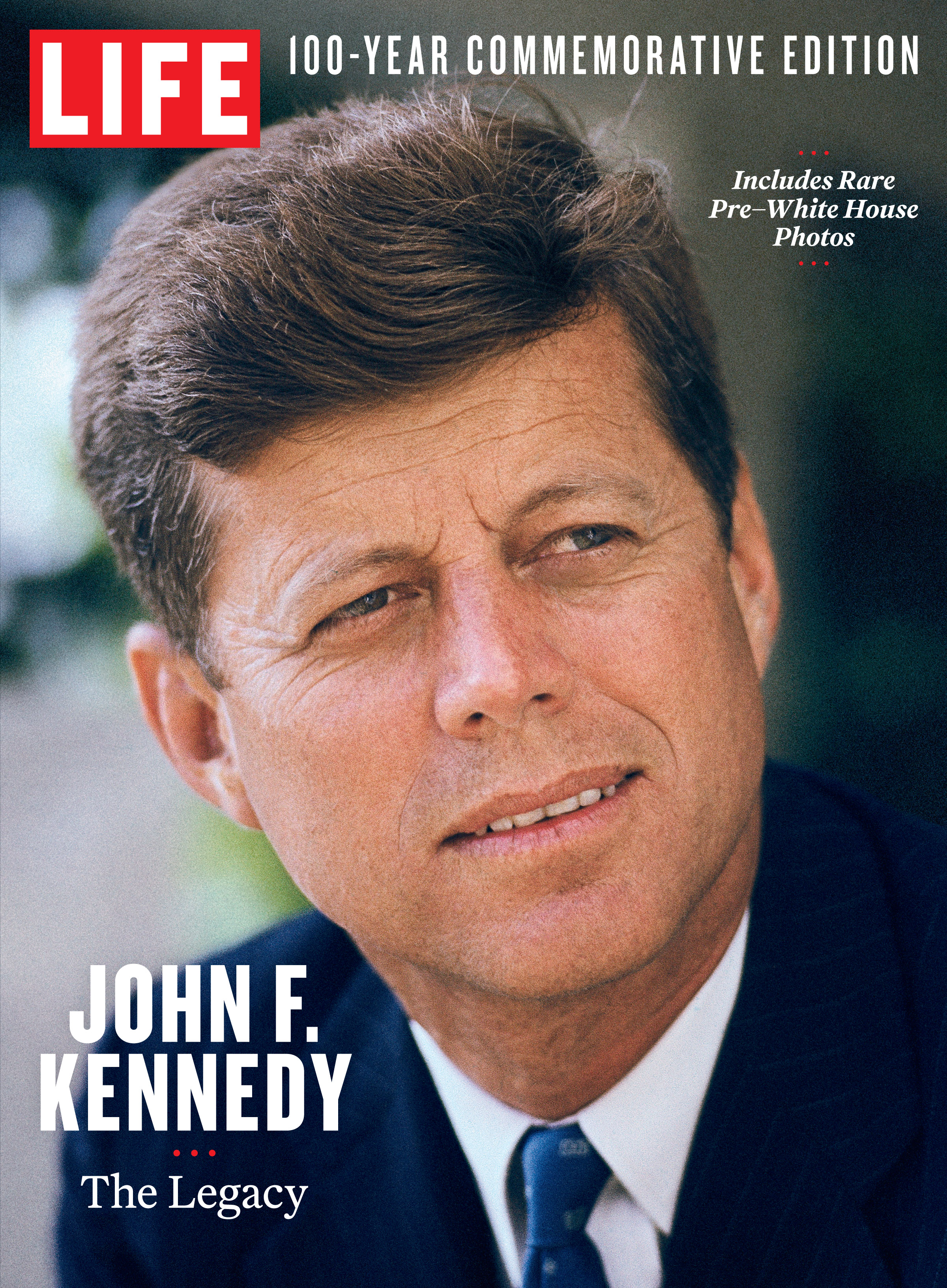

Read an excerpt from LIFE’s new special edition, John F. Kennedy: The Legacy

John F. Kennedy was born at home, in a three-story Colonial in Greater Boston, in late May of 1917, the same springtime in which America entered World War I. He was delivered into one world war and he blossomed into public adulthood during the next, a hero at sea. It may be that no one else born in 1917, or in any year since — oh, well, Elvis maybe — has taken and fulfilled America’s imagination as Kennedy did. No one else who represented so handsomely and succinctly the sense of what the country had been and what it might become. He is still the youngest U.S. President ever elected, and still the youngest to die.

Kennedy has been gone for more years than he spent on earth. And yet nearing the occasion of what, in some incalculably different history, might have been his 100th birthday (his mother, Rose Fitzgerald, lived to 104) he can even now feel enormously present. We have known the stories: the legends and the truths that have shifted and grown and been burnished and chipped over the decades. Raised in a kind of American royal family, groomed for political life. The ascendant career, the dazzling bride, the podium eloquence, the troubles with Cuba, the stand against the Soviets, the drive for Civil Rights, the other women, the moon, the trip to Dallas in November of 1963.

During his presidency and now in the long aftermath, the Kennedy contradictions have sharpened. Slim and physically compromised — asthmatic as a child, he later fought Addison’s disease, and colitis, and his chronic back pain sometimes had him on crutches — he was nonetheless the clearest symbol of American robustness and vitality from the moment, in his September 26, 1960, debate with Richard Nixon, that he looked straight into the television camera and began to speak. Ten words in, Kennedy invoked Abraham Lincoln. Then he spoke about the United States’ commitment to freedom and strength and equality, and the individual talents of all Americans. By the time he was done with his opening statement, the art of presidential campaigning, and the nation’s image of a leader, would never be the same. “I subscribe completely to the spirit that Senator Kennedy has expressed tonight,” Nixon said in his response.

The most enduring of Kennedy’s messages tend to be about shortening the distance between people, never about wedging people apart. “Ich bin ein Berliner,” he declared in June of 1963 before thousands of assembled Germans and in response to the erecting of the Berlin Wall. You are one, and I am one with you. Five months later, on the sunlit afternoon when the presidential motorcade prepared to ride through the crowds at Dealey Plaza, it was Kennedy who insisted that he and Jackie travel with the car’s top taken off.

Midway through his inaugural address, the speech in which he implored citizens to “ask not what your country can do for you…” Kennedy also said this: “If a free society cannot help the many who are poor, it cannot save the few who are rich.”

This was a bedrock notion for Kennedy, who was keenly aware of his privilege, and a bedrock notion for the Kennedy family at large. At the 1992 Democratic National Convention, Ted Kennedy, JFK’s younger brother and a long-term senator from Massachusetts, addressed the crowd. “The true test of society is how it treats the least fortunate within it,” he said.

And then, this year, in March, Joseph Patrick Kennedy III, the great-nephew of JFK, and a fourth-year congressman, took to a microphone at a House committee meeting to engage in the ongoing battle to provide health care for the poor. It was a battle that Ted had fought for years. “We are judged,” Joe III suggested, “not by how we treat the powerful, but by how we care for the least among us.”

Perhaps such words would have been spoken in that chamber, in that circumstance, regardless of whether the world had known John F. Kennedy. It’s not a unique instinct after all, but it is a surviving one. “A man may die, nations may rise and fall, but an idea lives on,” JFK said in ’63. And that big idea — of America, even the world, as one people, looking after the weak — is the idea that John F. Kennedy projected, that still clings to him today.

Read more in LIFE’s new special edition, John F. Kennedy: The Legacy

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com