Speaking to the American writer and academic Richard Burgin in 1967, Argentinian writer and essayist Jorge Luis Borges relayed a story in which his father analogized childhood memories to a stack of coins. Explained Borges: “He piled one coin on top of the other and said, ‘Well, now this first coin, the bottom coin, this would be the first image, for example, of the house of my childhood. Now this second memory would be a memory I had of the house when I went to Buenos Aires. Then the third one another memory and so on.” In each coin lay a distortion, his father said, a kind of confabulatory glitch that led the father to try not to think about the past for fear of misremembering. “And then that saddened me,” said Borges. “To think maybe we have no true memories of our youth.”

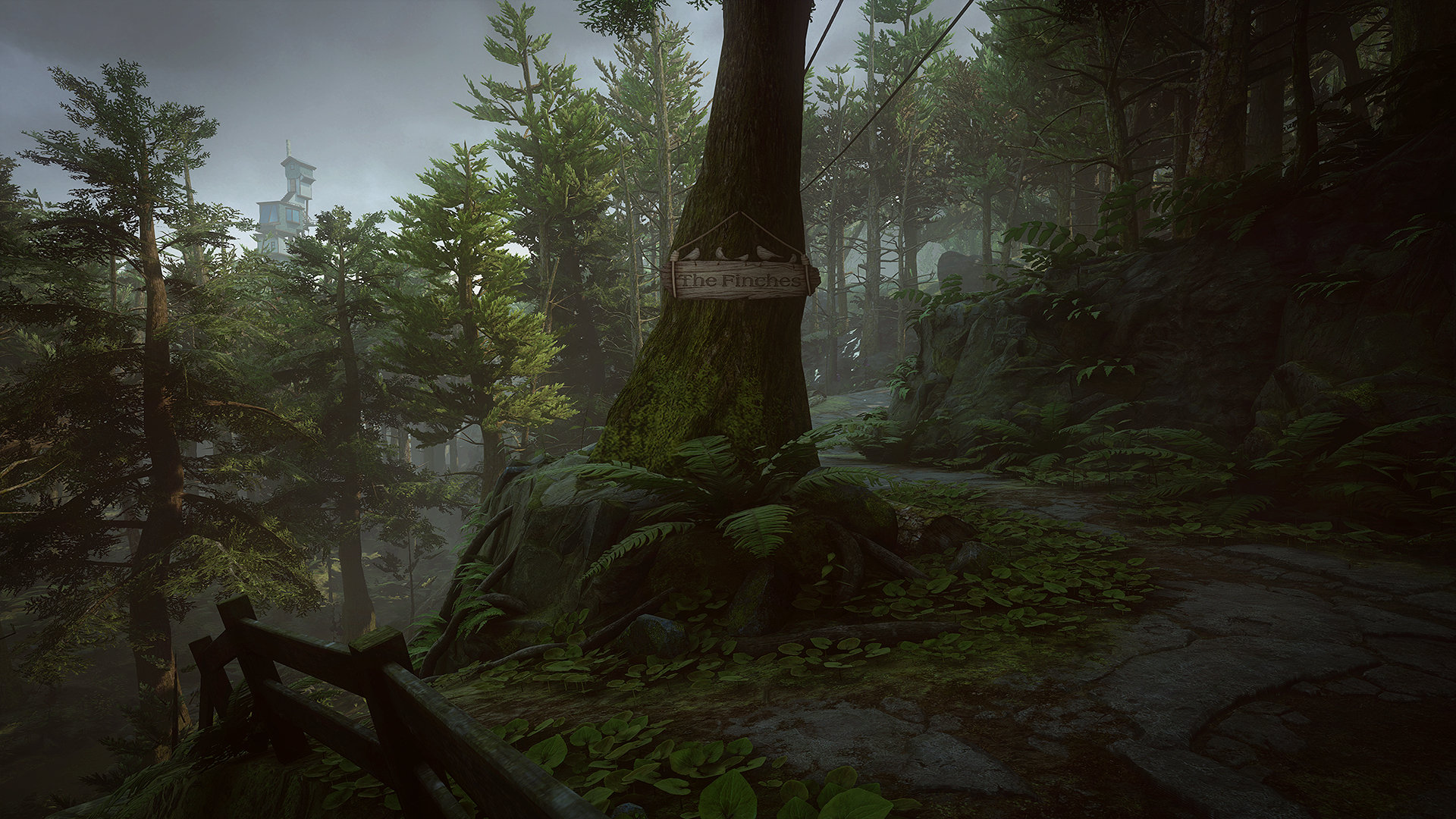

In Giant Sparrow’s sophomore effort What Remains of Edith Finch, an interactive journey through the puzzling lives of a family beset by tragedy that arrives April 25 for PC and PlayStation 4, phantom memories lurk behind secret doors or at the ends of twisting passageways. The setting, a remote Pacific northwest home whose oblique additions sprawl like a stack of teetering favelas, becomes both a literal maze and a lineal metaphor — a multigenerational map of attachment and dysfunctionality.

Players navigate the home as Edith, the game’s Virgil and ostensibly the last surviving Finch, returning to her ancestral abode years later. The house is silent though never quite sinister, a forlorn fairy tale construct surrounded by disquieting trees but also beautiful, aglow in the setting sunlight. Inside, books clog hallways and spill from tables, piled behind furniture or jammed over archways like bibliophile decor. A few of Borges’ novels join others by the likes of Mark Danielewski, Marcel Proust, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Robert Chambers and David Foster Wallace — one set of games signaling to another.

“Nothing in the house looked abnormal, there was just too much of it, like a smile with too many teeth,” says Edith at one point, her wry or wistful observations paralleled by subtitles that materialize over attendant objects before dissolving or playfully shuffling offstage.

As in other storytelling experiments, like Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture or Virginia, making progress here isn’t about decoding messages or thwacking bad guys. Instead, you wander at leisure through solemn spaces designed to offer as much or as little information as you’re willing to gather through patient observation. Locks and peepholes beckon. The artifacts of unfinished lives wait inches behind doors in some cases bolted half a century ago. It’s like being the single autonomous presence in a melancholy museum, witness to the bric-a-brac of the dead, each inanimate tableau charged with meaning. You can race though the house clicking on conspicuous visual triggers that set the next sequence in motion, but you’ll miss much of the tale.

It’s an exceptionally well-told story, an anthology of remembrances experienced through the eyes of each family member at the precipice of their demise. The novelty here lies in these tellings, each vignette unfurling like a piece of gameplay snapped off from some other game, singular and fascinating. One of my favorites contrasts a patent act of drudgery with one less obviously so (but that will be immediately familiar to gamers), challenging players to engage both simultaneously as the story builds. Another simulates a thing we’ve all imagined doing on a swing with awesome grandeur. The most powerful involves an infant, its happy life extinguished in a masterful sequence as movingly whimsical as it is distressing and indelible. Whatever beauty there may be in dying, Giant Sparrow seems to have found it here.

The lie in the sort of story that involves death on a scale that culminates in the near extinction of a family is that something supernatural must be responsible, a curse, say, or a vengeful ghost. A more honest and unnerving engagement might entail grappling with the caprice of a universe that metes out misfortune indiscriminately. Terrible things happen to well-meaning people, sometimes on aberrant orders of magnitude. All we can do is try to honor and understand what remains, to build our tiny coin towers against the darkness that eventually comes for us all.

4.5 out of 5

Reviewed on PlayStation 4 Pro

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Matt Peckham at matt.peckham@time.com