Gurwitch is an actress and New York Times bestselling author; her new collection of essays, Wherever You Go, There They Are: Stories About My Family You Might Relate To, has been published by Blue Rider Press.

Growing up in Miami Beach of the 1970s, I was a stoner at a time when casual usage was so common that my parents were my suppliers. During high school, I slowly burned through their stash: a plastic bag stocked with neatly rolled joints I discovered in my mother’s socks drawer, assuming that they were also partaking. Only years later did my parents reveal that they tried it only once, but never said anything, on the assumption that they were accurately monitoring my pot smoking. Who was more naïve?

An occasional adult toker myself, I never imagined that as the mother of a teenager I’d feel compelled to adopt a zero-tolerance policy and assume the role of household drug-enforcement agent. But since the legalization of medical marijuana in Los Angeles, it seems like the fragrant scent of weed wafts from every open window, and I’ve witnessed too many of our kids turn their reusable water bottles into bongs and, aided by the rise in other prescription meds, to be sure, slip into an over-medicated malaise.

This was my thinking when my mother’s cancer spread to her bones in the summer of 2014 and she began experiencing symptoms of neuropathic pain. The kind associated with chemotherapy is often described as a numbness or burning sensation in the hands. But according to my mother, it felt like she’d lost control of her appendages. “My fingers are going in different directions,” she once said while grasping and squeezing her hands, trying to control the errant behavior.

Acupuncture and massage have shown promise in abating symptoms of peripheral neuropathy — but if they were covered under my mother’s health insurance, I wouldn’t know. It proved impossible to navigate the byzantine labyrinth of benefits information. Over a six-month period, during which she was both distressed and depressed, I was able to get her general practitioner, the only provider authorized to make referrals for palliative and mental health care, on the phone only once — and that was only after I pretended to be a doctor so that I could get his back office number and call him directly. Providing holistic care for a woman in her late seventies was simply not a priority. It was easier to call in refills for opioids.

I looked elsewhere. Florida, where my mother resided, is one of 29 states where medical marijuana legislation has passed. Yet despite the growing use of cannabinoids as an alternative to prescription drugs for the elderly, if you’re living in a facility where this treatment isn’t supported — much less administered — like my mother was, all bets are off.

So, what do you do as a daughter cobbling together her mother’s care but living 2,733 miles away? You become your mother’s drug mule.

The first step was to locate a doctor. Anyone who’s seen movies set in Los Angeles is familiar with Beverly Hills’ broad boulevards lined with royal palms. A different foliage is more widely represented in less monied neighborhoods. Billboards advertising doctors’ offices with cannabis leaves wrapping around a caduceus crowd every commercial street corner.

I pulled up in front of The Doctor’s, a walk-in facility in a mini-mall, but thought better of it. The misapplied apostrophe seemed just a bit too sketchy. Who’s to say I wouldn’t leave with one less kidney than I walked in with?

I passed up the opportunity to be seen by Dr. Ganga because although a nom de plume is a recognized literary convention, I prefer to visit medical professionals who work under their legal names, not a nom de doobie.

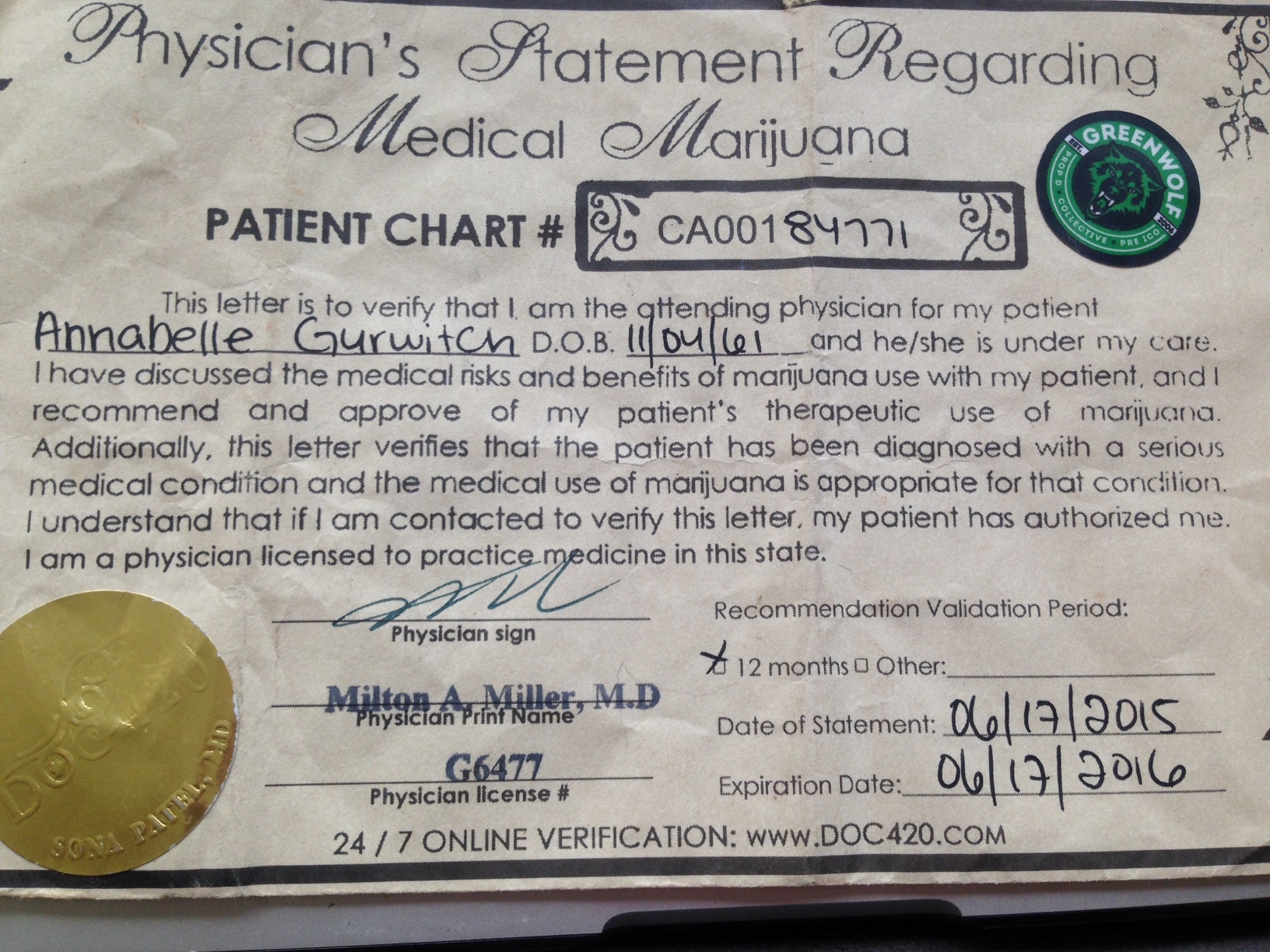

Nonetheless, I wound up under the care of Doctor420, who operates the only medical office I’ve ever visited that sells Flamin’ Hot Cheetos. My exam took all of three minutes. “Arthritis,” I said, holding up my crooked right pinky — but he was already filling out the required paperwork. I was awarded a medical license that looks as official as any of the student-of-the-month certificates my son earned in kindergarten.

Next, I consulted experts: On the recommendation of underage teens, I discovered that the pharmacy with the largest selection of edibles near my home is a collective located across the street from a Toys R Us and within walking distance of two local schools. There I found an industry trying to go legit while selling medicine labeled Blue Space Zombie Resin, Pineapple Trainwreck and Yoda’s Brain. I purchased candy infused with THC (the stuff that gets you high) — both those designed for recreational usage, as well as those strictly delivering cannabinoids associated with pain relief in varieties ranging from lemon drops to gummy worms and chocolate bars. My mother’s “prescription” was filled by a lithe saleswoman with a Hello Kitty tattoo on her neck.

Back at home, guided by my ten-minute tutorial from Nurse Neck Tat, I printed out instructions notating percentages of THC and recommended dosages. Channeling my inner Walter White, I secreted the medication into unmarked baggies and labeled the package in handwriting markedly different from my own as a precaution against identification and forgoing a return address.

Would the products I purchased prove too potent? Not potent enough? Would they have a more deleterious effect than the cancer already ravaging her body? I cast aside my concerns and, focusing on how the swelling in my mother’s feet was now making walking painful, I committed a federal crime. I sent the package by UPS Ground on the assumption that it would attract less attention than by air.

A week later, my father reported the results on the phone: The chocolate tasted oily, but the lemon drops were a godsend. Could I bring more on my next trip down to Florida?

“If you get arrested, that could hurt your chances of employment,” my sister, an attorney, worried after I told her.

“At my age, fifty-five, what’s hurting my chance of employment is my age!” I told her. “Besides, I’m only flying into Miami International Airport, historically a hub for drug traffickers, so what could go wrong?”

I passed undetected by packs of drug-sniffing dogs stationed around the airport. My father sighed when I handed over the baggie. “Thank you,” he said.

By this time, my mother was recovering from a cancer-related surgery in the hospital on the campus of their senior-living facility. We ambled into her room, and my father, who was never much of a caregiver — much less a compassionate spouse to begin with — showered her with affection.

“How’s my beautiful wife?” he said, kissing her cheek and unpacking an assortment of cherries and other fruits that were prohibited from her diet. Still, it was a heartwarming gesture.

She was anxious and uncomfortable, so I offered her a THC-infused Swedish fish. “I’ve brought you some new flavors to try. I’m so glad it’s helping, Mom.”

“Oh, no, I’m not taking them, but your father loves them.”

I was shocked, but that explained his sudden personality change. He was the only one availing himself of the “medibles.” Over the next days, I marveled as my father, who’d been previously overwhelmed, calmly weathered my mother’s agitated state. For their anniversary, a date he’d rarely remembered in 58 years, he bought a small bottle of champagne to celebrate. Was he suddenly fearful of losing her? Maybe. Was he high as a kite? Who cared? In the entirety of their marriage, I’d never witnessed so much kindness on his part.

After that visit, I stopped purchasing the strains that only delivered pain relief and stuck to mood-enhancing treats. Brazenly flouting the law, I carried Kush Kake Pops and other “baked” goods in their original packaging on flights down.

While caring for my mother, my father suffered heart failure and died soon afterward. My mother’s health declined precipitously, and she began experiencing shooting nerve pain along her spinal cord. I encouraged her to give the edibles a try, but you’re supposed to stay ahead of the pain, and we’d fallen so far behind. We gave the hospice nurses permission to administer stronger and stronger doses of prescription medication as needed.

My mother passed into a morphine-induced coma and took her leave on the day of my father’s memorial. If I’d been able to craft an effective regimen of cannabinoid-based pain relief, would that have changed the trajectory of her disease? It’s doubtful. But it’s undeniable that my father’s consumption improved the quality of their lives. The efficacy of cannabis for caregivers hasn’t been studied, but our experience suggests it’s a worthy area of investigation. No matter the future findings, of one thing I am certain: If what I did was a crime, you can arrest me now.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com