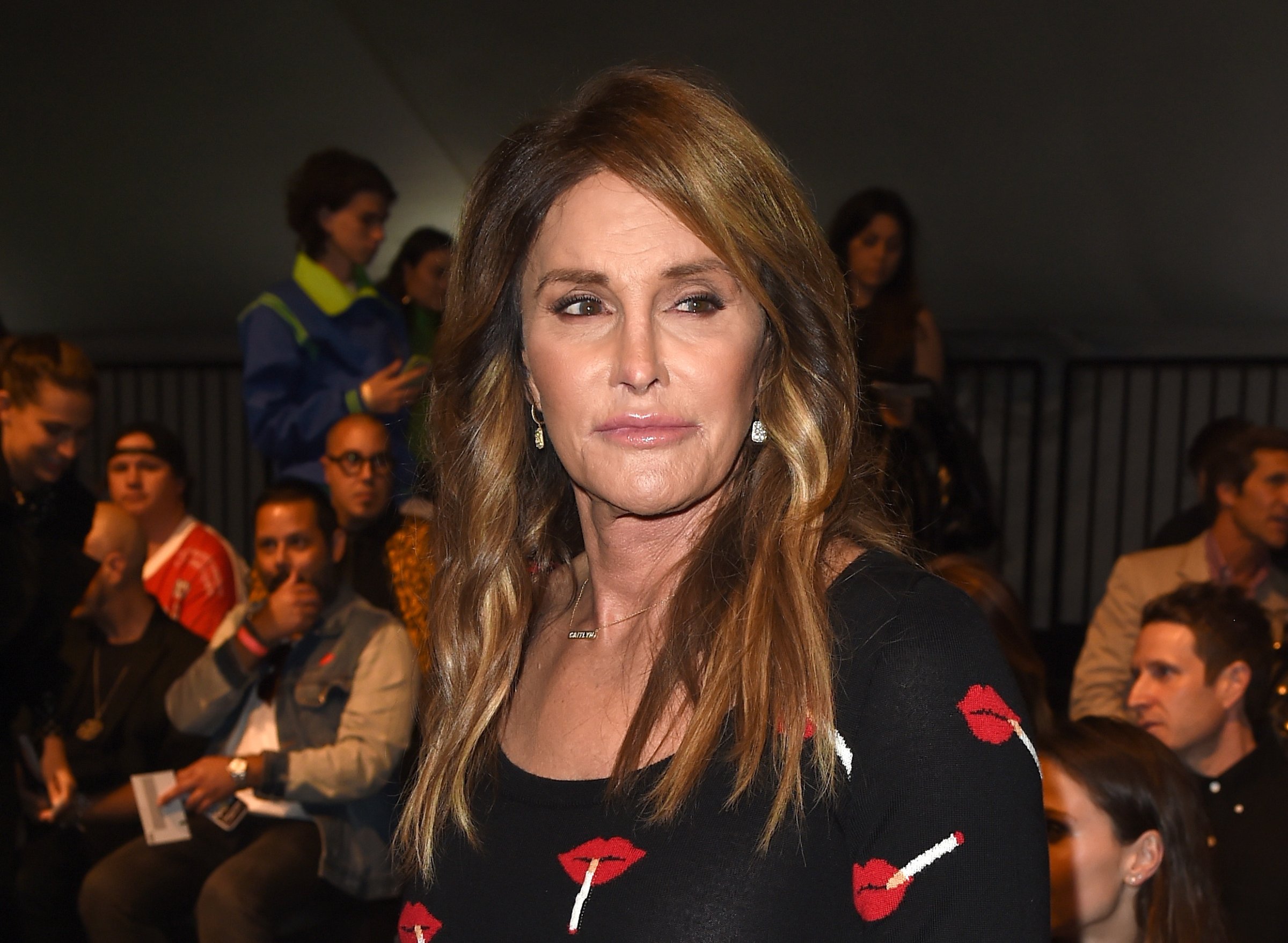

For weeks now, Caitlyn Jenner’s genitals have been something of a trending topic. And while that’s problematic, it’s not very surprising.

The American public has long been fascinated by the medical details of transitioning, with transgender people regularly asked in media interviews what is under their clothes. And while awareness and acceptance of transgender rights in the U.S. has grown by bounds in recent years, the hubbub over Caitlyn Jenner’s revelation that she has had gender reassignment surgery is a reminder of just how prying the conversation remains.

In an interview on Friday with Diane Sawyer on 20/20, Jenner confirmed that she had “final surgery,” as she puts it in the her new memoir, The Secrets of My Life. She also emphasized that, “I wasn’t less of woman the day before I had the surgery than I was the day after I had the surgery.” And she issued what Sawyer characterized as a social warning: “I would make a suggestion to all people out there: Don’t ask that question.”

As soon as news of the revelation leaked, in the weeks running up to the interview, outlets started running stories that referenced her body parts in the headlines. On CBS’ The Talk, the hosts sat around casually discussing whether she had a “willy,” what she “did with it” and how “it’s working down there.”

The focus on Jenner’s surgery reflects misunderstandings of what it means to be transgender, and it deepens the incorrect perception that gender and sexuality are one and the same. While surgery can be an important, life-altering process for some transgender people, members of that community have been pushing back on the prurient curiosity about their bodies for both personal and political reasons.

“It objectifies us and in the process dehumanizes us,” says Julia Serano, an author and transgender woman, noting that there has long been “a lack of thinking about what it would be like to be on the other side of those questions.”

The curiosity can seem innocent, even if the effect is not. “We have this sense of people becoming public property when something unique is known about them,” says Jamison Green of the World Professional Association for Transgender Health. He draws an analogy to pregnant women getting approached by strangers who want to touch their bellies without even knowing their names.

Advocates say that focusing on surgery perpetuates the idea that gender is nothing more than genitals, in an era when transgender people are fighting for government institutions to recognize a person’s gender based on their sense of identity and for society as a whole to accept those identities as valid.

“It’s very important for people to know that medical transition is not what makes someone a man or a woman,” says Nick Adams, who monitors representations of transgender people in the media for the advocacy organization GLAAD. “We are who we say we are,” says Adams, a transgender man. Jenner’s comments about having surgery on 20/20 echoed those sentiments: Gender is “about what’s between your ears and who you are as a person. It’s your soul, okay?”

Transgender people do make use of a range of medical procedures. Steps such as hormone therapy can help ease a painful disconnect that many transgender people experience between their body and mind. Such interventions, when desired, are recommended in the standards of care for people with gender dysphoria. But a lot of transgender people can’t have – or don’t want – surgery.

The list of possible reasons is long: it’s expensive and insurance companies have long excluded coverage for it; surgery is risky and can be scary; a partner might object; it might affect the ability to have kids; some have religious reservations about body modification; others have health conditions that preclude it; and some people simply do not feel that they need it. The fact that surgery is not available to everyone has motivated some government agencies, like the State Department, to move away from treating it as a dividing line between who is officially viewed as male or female.

“For many people it can become the focus of their life, but not everybody,” says the National Center for Transgender Equality’s Mara Keisling, whose organization has lobbied to get better medical coverage for such procedures. In a large scale survey the center released last year, almost all transgender men said they wanted “top” surgery to alter their chests, but about a quarter said they had no interest in “bottom” surgeries. And while almost all transgender women said they wanted some form of electrolysis or hair removal, between one-third and half of them said they did not want – or might not want – more major procedures like chest augmentation or a vaginoplasty.

The notion that having surgery makes a transgender person more “valid” or “complete” as a man or woman can create a fraught sense of hierarchy for some transgender people, especially for those who want surgery and can’t afford it. Transgender people have also struggled against the notion that have to prove they are men or women. “These are problems trans people often have to deal with in our day to day lives,” says Serano, adding that those difficulties are exacerbated by the idea that “if they haven’t had surgery, there’s something wrong with them.”

Serano has argued that the most important factor that affects someone’s experience of gender is “whether people perceive us as male or female and how they treat us.” And outside of the bedroom, she adds, it is very rare that a person’s genitals come into those split-second judgments one makes countless times a day.

Plenty of transgender people have been open about having surgery, writing about it in their memoirs or documenting their transition on their YouTube channels. People talk about it because “it was a personal experience that was really important to them,” says Serano. And many have said they’re trying to demystify the process and provide examples for young people that they did not have when they were growing up.

Handled sensitively, a discussion about surgery in a media interview can serve as a learning experience. Keisling, of the National Center for Transgender Equality, emphasizes that Jenner has every right to talk about whatever part of her story she wants to. “It is perfectly great if she thinks that was important to her and she was able to access it,” she says. “There’s some concern that it could reinforce the misunderstanding in the public that this is part of everybody’s story, and that is just part of the challenge.”

Advocates say that the focus on surgery has eased since a viral moment between Katie Couric and actress Laverne Cox a couple of years ago. On her daytime show Katie, Couric said to transgender model Carmen Carerra, “Your private parts are different now aren’t they?” Carrera hadn’t brought up surgery and squirmed, saying she didn’t want to talk about it, that she would rather talk about appearing in magazines or her family goals.

Appearing later in the same show, Couric asked Cox what she thought of Carrera “recoil[ing]” at the question, and Cox expanded on why journalists should not focus on genitalia. “The preoccupation with transition and surgery objectifies trans people and then we don’t get to really deal with the real, lived experiences,” Cox said, citing harrowing statistics about the incidences of discrimination, violence and poverty transgender people face.

The exchange became something of a turning point. Cox later told TIME in another interview that she had “never seen someone challenge that narrative on television before.” Couric, who later apologized and called herself an “insensitive buffoon,” spent time exploring the difficulties transgender people face in another show. Since that moment, GLAAD’s Adams says he has seen more “transgender people realize they themselves could be more proactive in the way they created boundaries.”

Sawyer spent just a few minutes of the show on surgery, dedicating much more time talking to parents of transgender kids, discussing debates over bathrooms and interviewing scientists working on how gender and biology might intersect. But the coverage of Jenner’s disclosure leading up to the interview, and Jenner’s own words about why she shared this fact, are proof that the sensational draw is still there.

“I am telling you because I believe in candor,” she writes in her memoir, according to People. “So all of you can stop staring. You want to know, so now you know. Which is why this is the first time, and the last time, I will ever speak of it.” Jenner also tried to close the book in the interview. “The media may,” she said, “but I am not going to dwell on that subject.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- TIME’s Top 10 Photos of 2024

- Why Gen Z Is Drinking Less

- The Best Movies About Cooking

- Why Is Anxiety Worse at Night?

- A Head-to-Toe Guide to Treating Dry Skin

- Why Street Cats Are Taking Over Urban Neighborhoods

- Column: Jimmy Carter’s Global Legacy Was Moral Clarity

Contact us at letters@time.com