In auteur Thomas Brush’s surrealist adventure Pinstripe, out for PC on April 25, players guide a lanky wisp of a man named Teddy through a hell of a different sort.

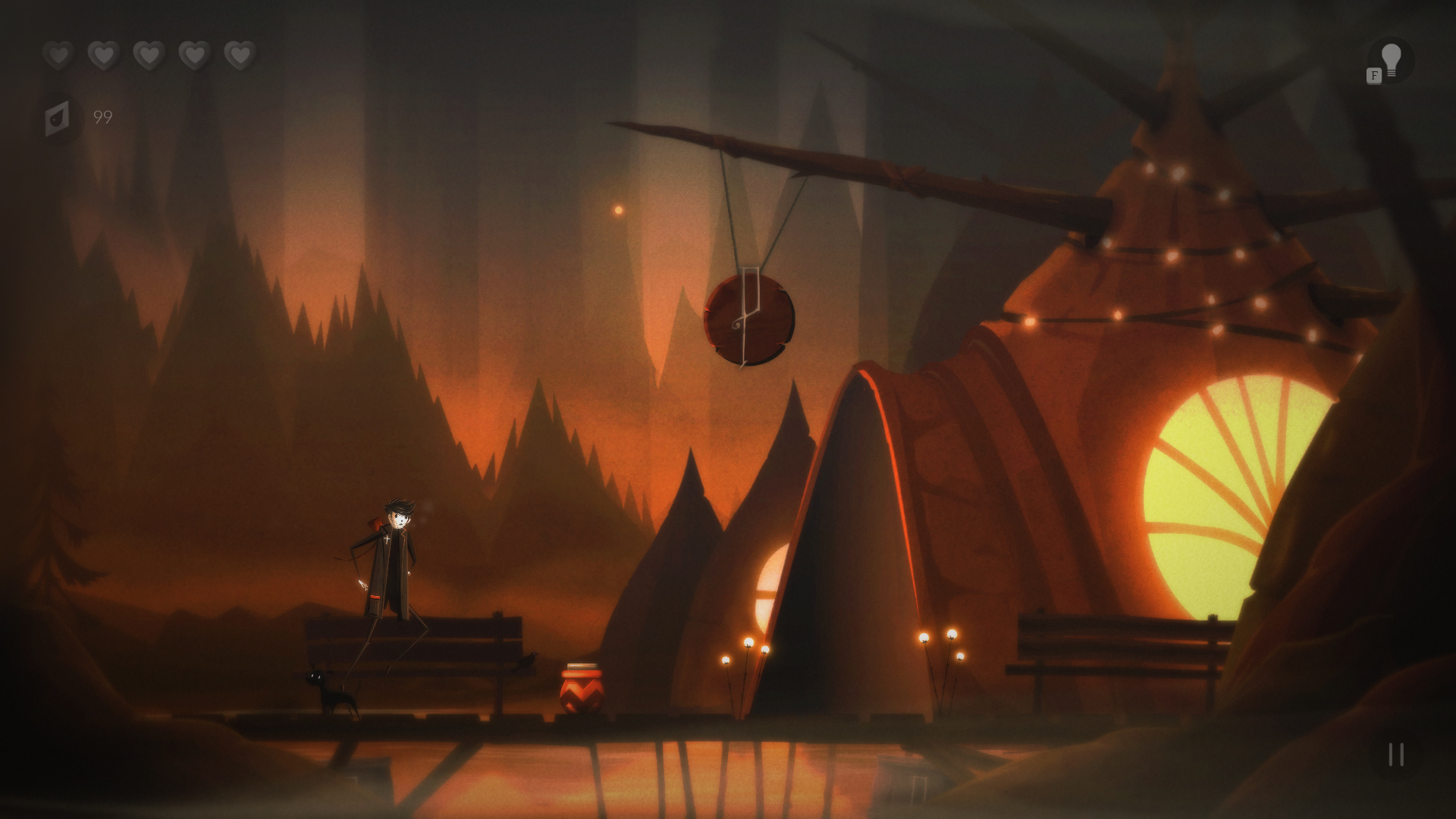

Ted is a priestly cipher who wears a coffee-colored topcoat atop legs like darning needles. On one lapel he sports a rood, below a white clerical collar underlining a haunted cartoon face, its frozen black “o” of a mouth framed by stubble and sable hair upswept like something styled by an electrical socket. The world about him is a melange of beauty and horror, a bricolage of dreamscapes and Tin Pan Alley tunes where the devil is literally in every detail.

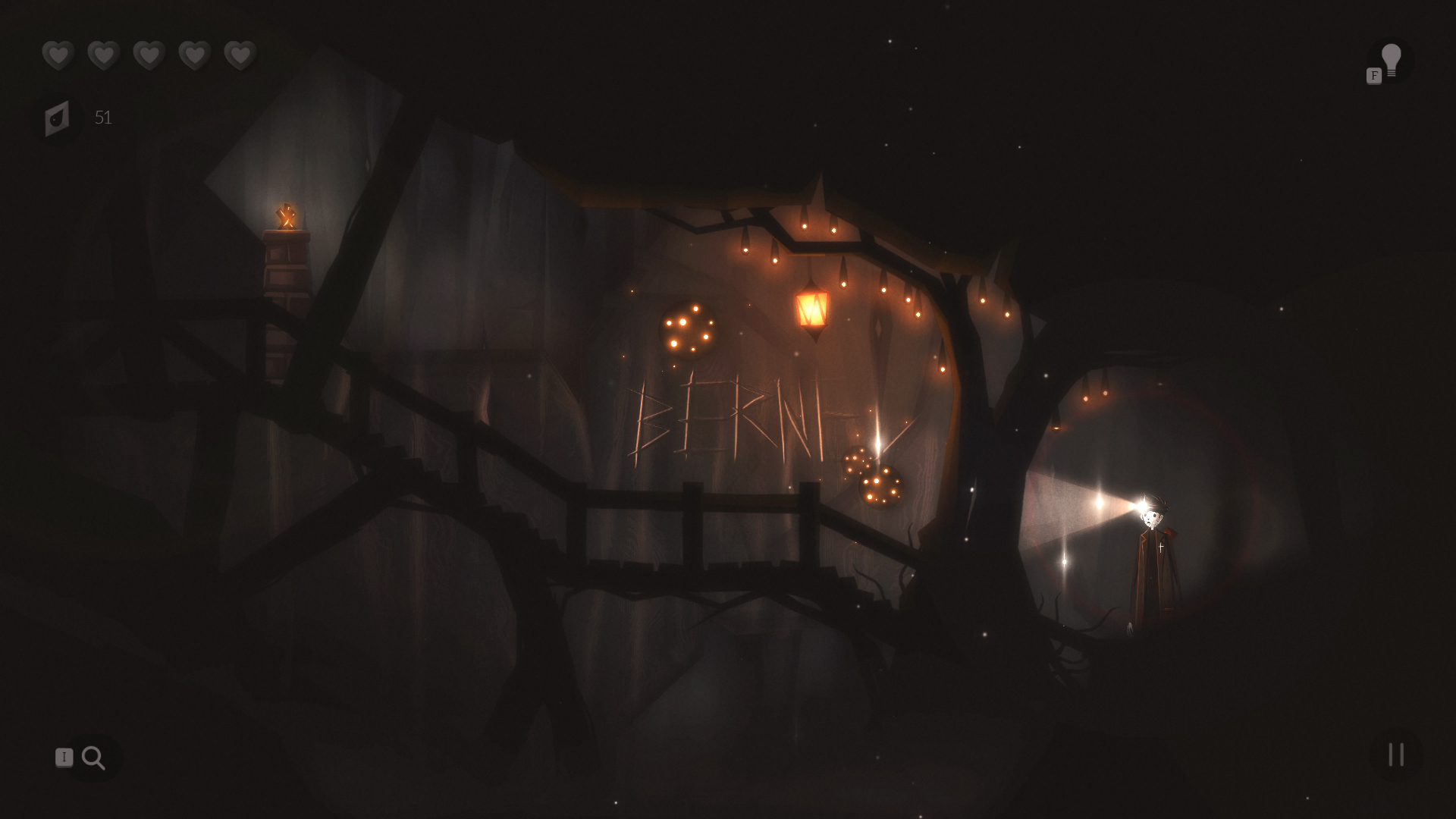

That devil, a pencil-thin, sable-garbed dandy who levitates like a dragooning marionette, has stolen Ted’s daughter. It is up to players to figure out how to get her back, but also to deduce what the heck is really going on. The world offers clues: piecemeal dates and mundane artifacts, words chiseled into the landscape like semiotic fingers, cryptic accusations from a cast of the abused who seem to know all there is to know about you and deliver baffling vituperations.

Brush, a one-man studio dubbed Atmos Games, is known for edgy Flash-based side-scrollers like Coma and Skinny. In those games, reality was similarly Janus-faced, a vehicle for Brush to produce evocative visual pastiches concealing something darker. Pinstripe represents the culmination of a five-year crowdfunded journey that imagines hell in geometrically minimalist terms, inspired by artists like Tadahiro Uesugi (Coraline) with tonal references to Tim Burton hues: battleship grays and midnight blues punctuated by the plaintive glow of sodium oranges and yellows. But also something of the absurd, those wistful vistas colliding with sleazy emanations and bathroom sounds. Exploring Pinstripe is like being seduced by, then recoiling from, a Bosch or Brueghel by way of Dante’s third circle and Kay Nielsen and Bill Tytla’s “Ave Maria.”

Its interactive language is simpler, a distillation of the shadow cast by Super Mario on a thousand games hence. Ted can vault between ledges or trampoline off springy objects to reach otherwise inaccessible locations. Early on, he comes across a slingshot, which he uses to fend off droning enemies or unearth hidden doodads by solving ballistic tests. Frozen oil drops scattered across scenes or sequestered behind obstacles serve as collectibles and fuel a simplistic barter economy that’s mostly about gatekeeping. Players often have to scrounge for sufficient quantities of drops to pay off some guy to give them a MacGuffin that unbars the way forward.

If the platforming feels orthodox, it’s the smattering of Myst-like puzzles that bears attention, a motley parade of serious and jokey brain and finger teasers that fit the ambient incongruity perfectly. Sometimes it’s noticing a route intentionally obscured after mapping out a level’s boundaries. Sometimes it’s a test of dexterity, a maddeningly timed puzzle that iterates across the game until by the end you’re hammering like a lunatic on the gamepad. Word puzzles and picture-matching diversions emerge. And if you opt to play the game twice, detours to optional areas redolent of Wizards & Warriors‘ precarious tree sequences gently pry back the fourth wall. There’s even a clever Flappy Bird reference crafted around locks and tumblers suggestive of the Stephen King line, “There’s an idea that hell is other people. My idea is that it might be repetition.”

Some things bear moderate repetition, of course, and Pinstripe‘s music would be one of them. The easiest way to describe it might be as the opposite of what you’d expect from a creator who lists Tim Burton and Lewis Carroll as among his influences. There’s little of the jaunty peculiarity of a Danny Elfman score here. Areas that could have been paired with sinister, brooding tunes are instead framed by contemplative motifs more reminiscent of C418’s melancholy approach to Minecraft. Brush, who also composed Pinstripe‘s musical score, has written that he views music as “the life-blood of a game. If the music doesn’t fit the artistic style and mood of a game, the experience can become disorienting.” That the music works so well against seemingly mismatched backdrops speaks well of his ability to put paid to those intuitions.

Pinstripe isn’t a game with grand twists of the sort that drive TV or film goers to social media frenzies. It feels more smartly made, fully aware that post-Ambrose Bierce rug-pulling tends toward cheap trickery too often masking cheaper material. Pinstripe has its surprises, but they’re mostly on the surface, the particulars just scaffolding supporting the game’s deeper emotional concepts, which link more with the ideas in Richard Matheson’s What Dreams May Come. What does loss resemble? How does it sound? What if the museums to mistakes that we spend lifetimes assembling in our minds were a physical space?

5 out of 5

Reviewed on PC

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Matt Peckham at matt.peckham@time.com