A few weeks after U.S. Secretary of State Rex Tillerson said that American “strategic patience” with North Korea is ending, a U.S. naval fleet is moving toward that country, prompting Chinese authorities to caution against further provocation between the two nations. As experts advise that North Korea seems ready to launch a new nuclear test, plans have been laid for a potentially large conventional strike by the U.S. against North Korean test sites and facilities, to be executed if North Korea goes ahead with another nuclear test.

Were President Trump to authorize such a move, it would represent the first time in the history of the world that any nation had launched a formal military attack on the territory of a declared nuclear state. It is perhaps no coincidence that this step is under consideration now that there is no one with any influence in government who would remember Hiroshima and Nagasaki as an adult. Yet it behooves us to revisit another instance in which the U.S. government flirted with a nuclear confrontation with another nuclear power — one that would have taken place, as it happens, in the same territory, Korea, in 1953.

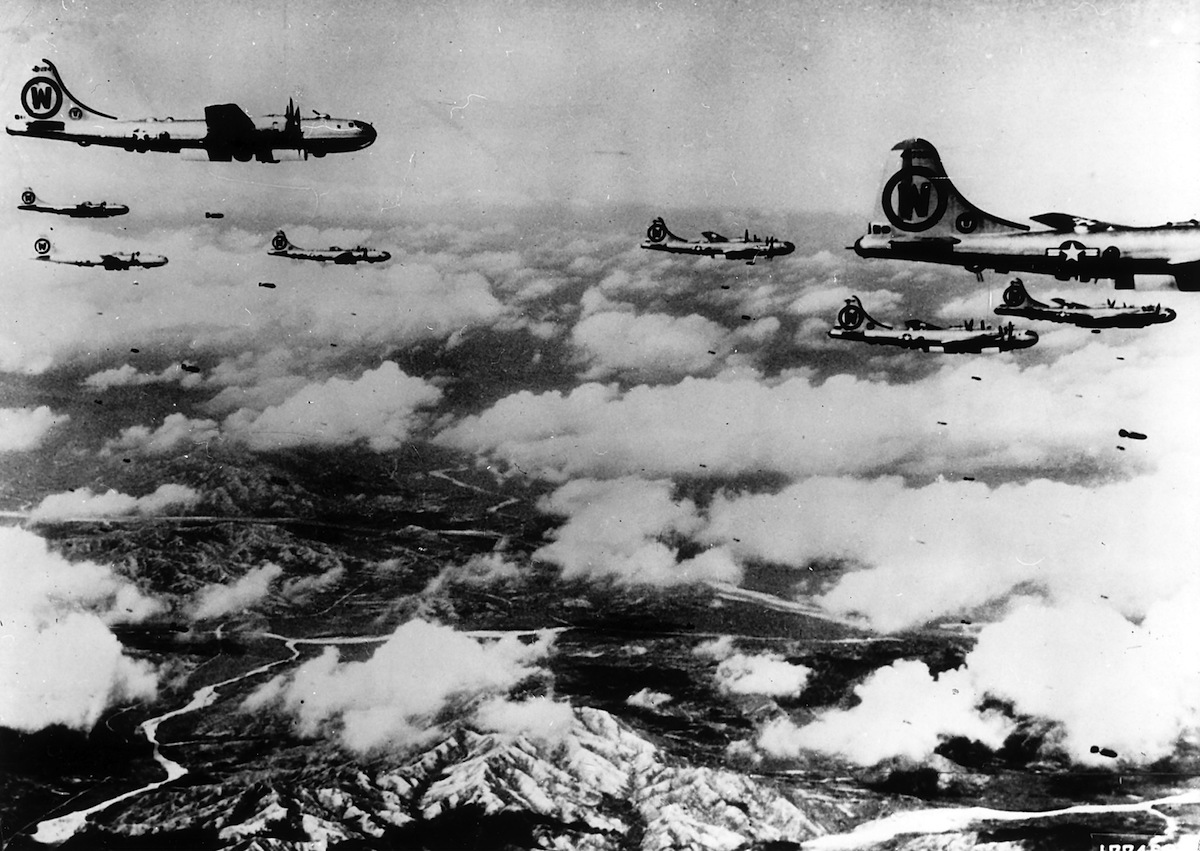

In 1953 the Eisenhower Administration — like the Trump Administration — took power in the midst of a long, frustrating, indecisive conflict. The Korean War had been stalemated for nearly two years, and President Eisenhower had promised to end it during the campaign and traveled to Korea before his inauguration. Upon taking office he ordered his administration to consider what would be necessary to go on the offensive in Korea again and re-occupy North Korea, as General MacArthur had done in late 1950, before Chinese intervention on the other side forced the U.S. and its allies to retreat to the South. Planners found that such an offensive would require a big new build-up of ground troops, and also suggested that the United States might want to use atomic weapons as part of the new drive north as well, even though the North Koreans’ Soviet ally already possessed a nuclear capability.

Leading civilians and military leaders discussed the possible use of atomic weapons in a meeting on March 27, 1953. Hardened not only by nearly three years of war in Korea but by the Second World War before that, these officials got to the heart of the matter in ways that we can only hope their counterparts today might emulate.

General Lawton Collins, the Chief of Staff of the Army, asked the first critical question: would the weapons be effective on the battlefield? “The Communists,” he said, “are dug into positions in depth over a front of 150 miles, and they are very thoroughly dug in. Our tests last week proved that men can be very close to the explosion and not be hurt if they are well dug in.” The parallel question today would ask whether American weapons — including the so-called Mother of All Bombs, which the U.S. has just used in Afghanistan — would in fact be able to disable underground North Korean nuclear facilities, and whether the U.S. really can locate all key North Korean nuclear installations.

Paul Nitze of the State Department, who for at least four decades insisted that strategic nuclear superiority was essential for the United States, raised closely related questions. The United States was now relying on atomic weapons to defend allies around the world, and if they did not work in Korea, allies might lose confidence in the U.S. We also had to ask, he said, “whether the USSR [which had exploded an atomic bomb nearly four years earlier]. . .might not decide to retaliate in kind.” Today the critically affected allies are the South Koreans and Japanese, and so far we have heard little or nothing about how they feel about this possible act of war on North Korea.

Yet the most interesting exchange was still to come. General Hoyt Vandenberg was Chief of Staff of the Air Force, the new service that was already pushing the idea that an atomic strike force could solve any national-security problems that the U.S. might face. “I hope that if we do use them,” he said, “we use them in Manchuria against the [Chinese] bases. They would be effective there.”

General Collins immediately raised a critical question in response — the question of retaliation. “Before we use them we had better look to our air defense,” he said. “Right now we present ideal targets for atomic weapons in Pusan and Inchon [the two major ports and U.S. base areas in South Korea]. An atomic weapon in Pusan harbor could do serious damage to our military position in Korea. We would again present an ideal target if we should undertake a major amphibious operation. An amphibious landing fleet would be a perfect target for an atomic weapon at the time when it was putting the troops ashore. On the other hand, the Commies, scattered over 150 miles of front, and well dug in, don’t present nearly as profitable a target to us as we do to them.”

Read more: How North Korea’s Nuclear History Began

Samuel Johnson once wrote that when a man knows he is to be hanged in a fortnight, it concentrates his mind wonderfully. Faced with a possible escalation to nuclear warfare, General Collins had grasped what remains the essential point about nuclear weapons: the only really important thing is not to have one dropped on one’s self.

Today the United States is not directly threatened by North Korea nuclear weapons — but Japan may be, and South Korea surely is. A nuclear detonation in either nation would be a catastrophe of untold proportions, not least because the 72-year-old taboo against the use of nuclear weapons would be lifted. The relatively stable international order that our parents and grandparents left to us would be gone forever.

As it turned out, things took a turn for the better in Korea in the spring of 1953. The death of Joseph Stalin in that same month of March led to a breakthrough in the peace talks, which had been stalled over the issue of the return of prisoners of war, and to the armistice that remains in force today. The U.S. lived with the nuclear-armed Soviet Union for another 36 years, until Communism collapsed. Things might have gone very differently had the United States normalized the use of atomic weapons by using them in Korea in 1953. A strike against North Korea’s nuclear capabilities would reflect the policy adopted by the George W. Bush Administration in 2002: that the U.S. will make war on any nation seeking weapons that we do not think they should have. North Korea, however, seems already to have developed usable weapons, and the North Korean government has stated its willingness to use them. Let us hope that senior Washington officials examine the situation with the same prudence that they did 64 years ago. Our children’s world may be at stake.

Historians explain how the past informs the present

David Kaiser, a historian, has taught at Harvard, Carnegie Mellon, Williams College, and the Naval War College. He is the author of seven books, including, most recently, No End Save Victory: How FDR Led the Nation into War. He lives in Watertown, Mass.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com