Hillary Clinton wasn’t the only female presidential candidate in recent memory to run against a man with popular appeal but little to no political experience. Ellen Johnson Sirleaf faced off against professional football player George Weah for the Liberian presidency in 2005. But unlike Clinton, Sirleaf won — and became the first woman elected president in Africa.

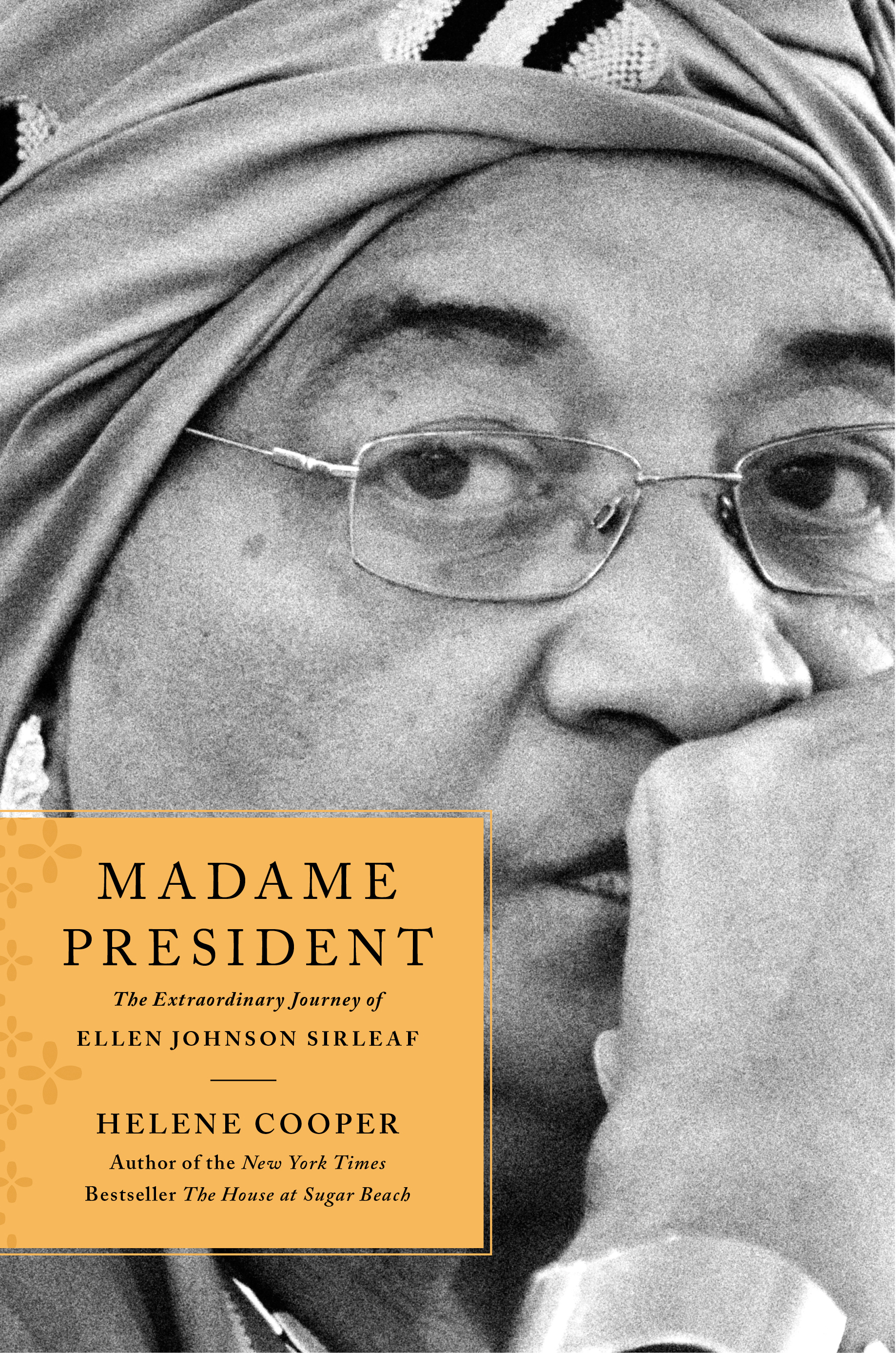

There are a few lessons Americans can learn from Sirleaf’s story, according to Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Helene Cooper, who recently published a biography of the Liberian leader. Madame President: The Extraordinary Journey of Ellen Johnson Sirleaf follows Sirleaf in her rise from a young abused wife to the leader of the West African nation — and the unlikely women’s movement that propelled her to power.

Cooper, herself born in Liberia, fled the country as a teenager with her family in 1980, following a coup led by Samuel Doe. She watched in horror from the U.S. as Doe and Liberia’s next leader, Charles Taylor, embroiled the country in civil war and violent unrest. When Sirleaf won the presidency, Cooper was stunned. “I remember feeling shocked and just unbelievably proud that Liberia, my own country, had done something that the United States still hasn’t done,” she told Motto. “These women who were so sick of the war collectively got together and staged a democratic coup to get a female elected president in one of the most patriarchal of places.”

After two terms — during which she was awarded a Nobel Peace Prize — Sirleaf plans to step down this year. Motto spoke to Cooper about the movement that carried a woman to power in Liberia, the leader’s flaws and her feelings about the end of Sirleaf’s presidency.

What brought Sirleaf into politics?

She was an abused wife. She got married when she was 17 and had four boys by the time she was 21. Her husband beat her, and she finally left him, got her college degree and went to work at a really young age at the ministry of finance, in the debt division. In the 1960s in West Africa, can you imagine a woman doing that? I think that started it. Liberia was founded by freed American slaves, and they set up the same antebellum society that they fled from in the American South — except this time they were the ones in charge, and the rest of the population made up the servant class. That imbalance led to a lot of the troubles the country had later on. Because Sirleaf had a German grandfather and a native Liberian grandmother, she was able to move in and out of both classes, and she was more aware of the inequity in the system. She was saying from a very young age that the country’s economic system was imbalanced and too tilted toward the rich. So that started her on her way.

In 1985 when Samuel Doe was president, Sirleaf was thrown in jail for being a political dissident. There, she met a young woman who you say galvanized her political ambition. How so?

The soldiers brought in a 19-year-old girl who had been gang raped. She was naked, crying hysterically and bleeding, and they threw her on the floor next to Ellen in her cell. Ellen sat next to her and was holding the girl as she’s sobbing, begged the soldiers to at least bring a piece of cloth to cover her, and they spent the night together. The next morning the soldiers came and took Ellen away. She never saw that girl again, but she talks about her all the time. I think that was a seminal moment for her, a moment when you see the kind of pain that’s being afflicted on the civilian population by the very same men, soldiers of the armed forces of Liberia, who are sworn to protect you — that really seared in her mind that she wanted to change things.

For all the great things Sirleaf has achieved, she’s also flawed. What was it like discussing her mistakes?

Sirleaf is very willing to play as dirty as she has to in order to get ahead. If you fling dirt at her, she will fling dirtier dirt at you. She’s deeply flawed. She supported Charles Taylor in the beginning, and we all know what Charles Taylor turned out to be. She admits it was a mistake. Also, I didn’t think she’d be as forthright about all the shady stuff she did. For example, she out and out told me about a $10,000 bribe that she gave to a warlord.

Are there meaningful comparisons to be drawn between the women’s movement in Liberia and the one happening in the U.S. today?

Sirleaf and Clinton are very similar in many ways. They are both highly educated, global bureaucrats with experience oozing out of their pores. They were both running against men who had basically no political experience. But when you look at the women’s movement in Liberia versus the one here, Liberian women had just come out of 14 years of horrific civil war. They had seen their children kidnapped and turned into child soldiers. Seventy percent of the female population in Liberia was raped. What was left of the economy was largely because of these women; they were the ones who kept making their wares and feeding the population, tending to the fields while the men were fighting. They realized in 2005 that they could turn that economic control into political control. They wanted to make sure they weren’t going back to war, and they believed that only a woman could guarantee that. We have so much sexism here in the United States, but the reality is that American women can, in many ways, have a far better standard of living.

Even if we can’t draw straight comparisons, are there lessons Americans can learn from Sirleaf’s story?

As a female presidential candidate, to succeed, and this was certainly the case with Sirleaf, you have to have a huge, huge percentage of the female vote. Because you’re not going to have a big percentage of the male vote, simply because you’re a woman.

Sirleaf is stepping down this year. How does it feel to see her presidency ending?

What’s weird is this has never happened before — we’ve never had a post-president in Liberia, somebody who voluntarily left at the end of their term. I’m glad to see it ending, because it means that when it was important, she played by the rules. It’s important to send a message to all these African dictators who don’t step down. As a Liberian, I’m a little bit worried about who replaces her, but one of the things she’s done really well is put in these safeguards for freedom of speech. I don’t think people will tolerate another despot. The women now know the extent of their political power, and I don’t think they will hesitate to exercise it, if it becomes necessary again.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Lucy Feldman at lucy.feldman@time.com