Starting next week, Arkansas will attempt something that’s never been done in the U.S.: execute seven death row inmates in a single state over the span of 11 days.

The scheduled spate of executions comes after Gov. Asa Hutchinson announced in March that one of the state’s execution drugs was set to expire by the end of April. The plan to beat that deadline has set off last-minute court proceedings, protests from anti-death penalty groups, legal challenges from pharmaceutical makers, and letters from religious leaders and former corrections officers urging the governor to reconsider. Family members of the victims, meanwhile, are looking for closure after decades of waiting for the executions to move forward. If they do, they’ll represent one of the most active periods for capital punishment in the U.S. since the death penalty was reinstated in 1976.

“In the modern history of the death penalty, no state has ever attempted to carry out this many executions in this short a timeframe,” says Robert Dunham, president of the Death Penalty Information Center, which opposes the way capital punishment is carried out in the U.S. “It’s unprecedented.”

Here’s what you need to know about the executions in Arkansas.

Why did the governor schedule the executions?

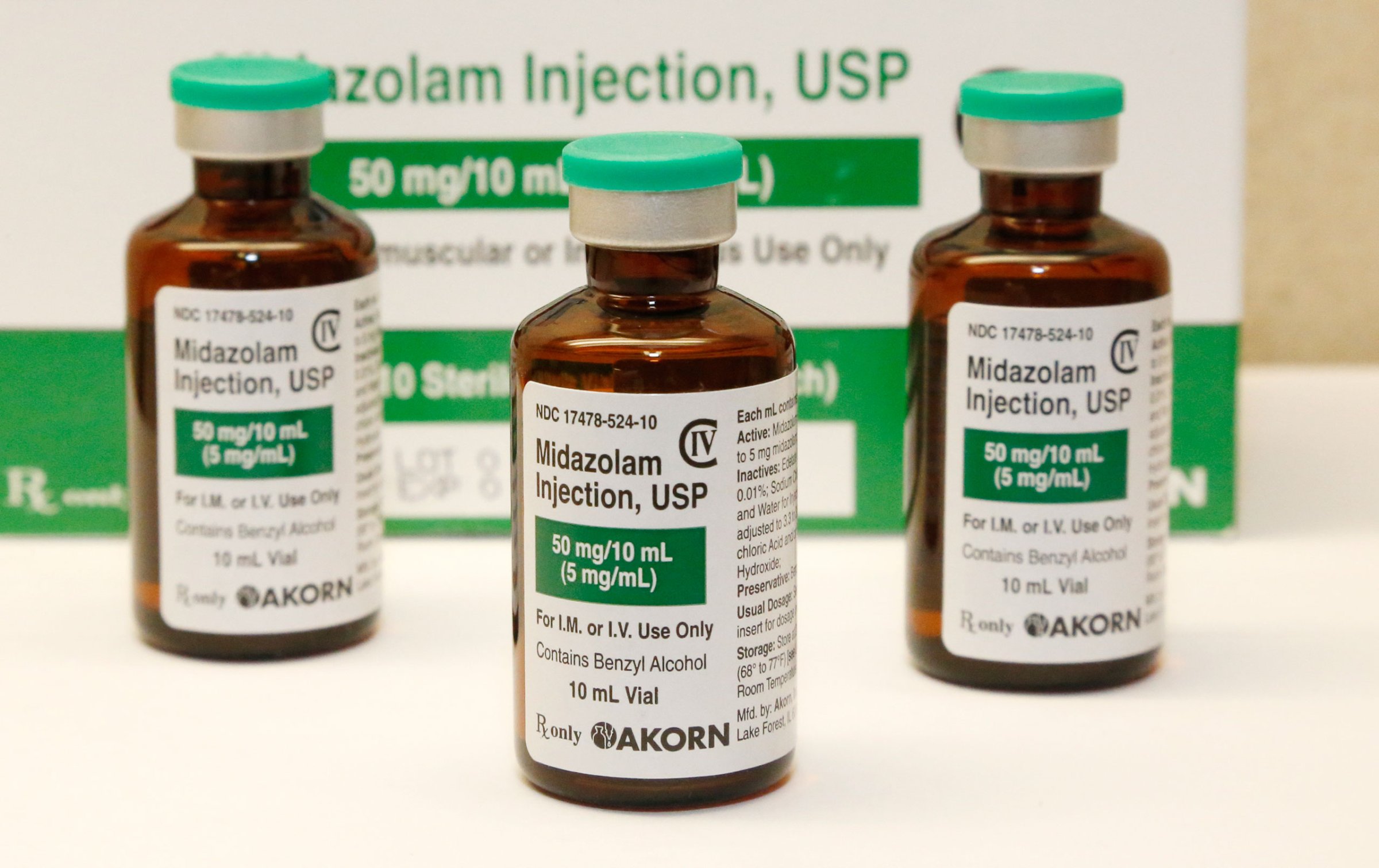

The governor, a Republican, said he made the decision to plan the executions within days of each other because the state’s supply of the sedative midazolam, one of three drugs used in lethal injections in Arkansas, would expire by the end of April.

“It’s not my choice,” Hutchinson said at a February news conference. “I would love to have those extended over a period of multiple months and years, but that’s not the circumstances that I find myself in.” The governor said it may be impossible to find another drug if the current supply of midazolam runs out and that he owed it to the families of the victims to carry out the executions. If the state does so, the executions will be the first in Arkansas since 2005. The state has executed 27 inmates since 1976, a fraction of the more than 1,400 that have taken place in the U.S. in the last four decades.

The governor’s decision is a sign of how problematic lethal injections have become for many states, which began having difficulty obtaining drugs around 2010 due to shortages and pressure from anti-death penalty groups. In response, many states have turned to midazolam, which has been at the heart of a number of executions that have gone awry in the last few years, including ones in Alabama, Arizona, Oklahoma and Ohio. The drug was also central to a 2015 Supreme Court case in which Oklahoma death row inmates challenged the constitutionality of using midazolam, arguing that there was no definitive proof that it properly rendered inmates unconscious. The court, however, ruled 5-4 for the state. The drug’s efficacy is still routinely challenged by death row inmates and anesthesiologists.

Who is Arkansas executing?

The seven death row inmates are all male; four are black and three white. They were all convicted of murder, and some of them received their sentences decades ago. According to the Fair Punishment Project, a group affiliated with the Harvard Law School, four of them appear to have either serious mental illness or an intellectual impairment. An eighth inmate was initially scheduled to be included, but a federal judge stayed his execution following the recommendation of a state parole board.

Lawyers for the seven condemned inmates, who have called the scheduled killings “execution by assembly line,” argued in federal court this week that the drug used by Arkansas is ineffective at properly sedating inmates and objected to the compressed schedule of the executions, saying they cannot provide proper counsel.

“We’ve never had that many scheduled in such a compact time, involving incredible stress on the system,” Jeff Rosenzweig, one of the inmates’ lawyers, told The Guardian.

But many of the victims’ family members say they’re ready for this chapter to close. Don Davis, one of the inmates scheduled to die on Monday, was convicted of killing 62-year-old Jane Daniel in 1990. Her daughter, Susan Khani, told NBC News: “We’ve suffered long enough and my mom really suffered that last day.”

She added: “I’ve been promised this for 25 years,” according to NBC News. “I just hope this time it goes through.”

Despite the court challenges, Leslie Rutledge, the state’s attorney general, says her office is committed to carrying out the executions.

“Attorney General Rutledge supports the death penalty and believes it is past time for the victims’ families to see justice for the horrible murders of their loved ones,” according to a statement from the attorney general’s office. “This office is prepared to respond to any and all challenges that might occur between now and the execution dates.”

Who opposes the state’s decision?

Arkansas’ executions come as support for the death penalty has dropped nationwide. According to a 2016 survey by the Pew Research Center, only 49% of Americans said they support the death penalty for those convicted of murder, the lowest point since the 1970s.

In the last few weeks, more than 200 faith leaders in Arkansas sent a letter to the governor urging him to reconsider the executions, as did more than two dozen former corrections officers. The Arkansas Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty is planning a rally on Friday to raise awareness about the executions. Even best-selling author John Grisham wrote an op-ed in USA Today urging his home state to “stop the execution madness.”

On Thursday, two pharmaceutical companies — Fresenius Kabi USA and West-Ward Pharmaceuticals — filed amicus briefs in an Arkansas district court, saying they believed the state illegally obtained the drugs for the executions. The companies have refused to supply drugs to states for lethal injections, and Arkansas has not disclosed where it got them.

While the efficacy of the drug remains a concern, the rushed schedule could bring its own challenges. Dunham, of the Death Penalty Information Center, says there are questions about the ability of executioners to carry out seven executions in such short a timeframe. He points to the problems involving Oklahoma’s 2014 execution of Clayton Lockett, who convulsed and groaned on the gurney and died 43 minutes after he was first sedated. It was the first of two executions scheduled for that day, but the second one was called off after problems with Lockett’s lethal injection. Oklahoma’s Department of Public Safety issued a report finding that officials involved in Lockett’s execution felt additional stress because of the back-to-back executions, which could’ve led to problems inside the execution chamber. The department has since recommended that the state only schedule one execution per week.

“If they botch one, there may be emotional effects that impair the ability to properly conduct the other,” Dunham says. The Death Penalty Information Center has tracked just 10 instances of multiple executions on a single day, the last one occurring in 2000. Deborah Denno, a Fordham University law professor who studies lethal injection, says that carrying out more than one execution already heightens the risk that something could go wrong — let alone seven in a week and a half with an often-criticized lethal injection drug. “We’ve never seen anything like this,” she says.

Still, the Arkansas Department of Corrections says it’s ready. Solomon Graves, a spokesperson for the Arkansas DOC, said via email that “training has occurred related to carrying out a sentence of death and the individuals involved are prepared to carry out their respective responsibilities.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com