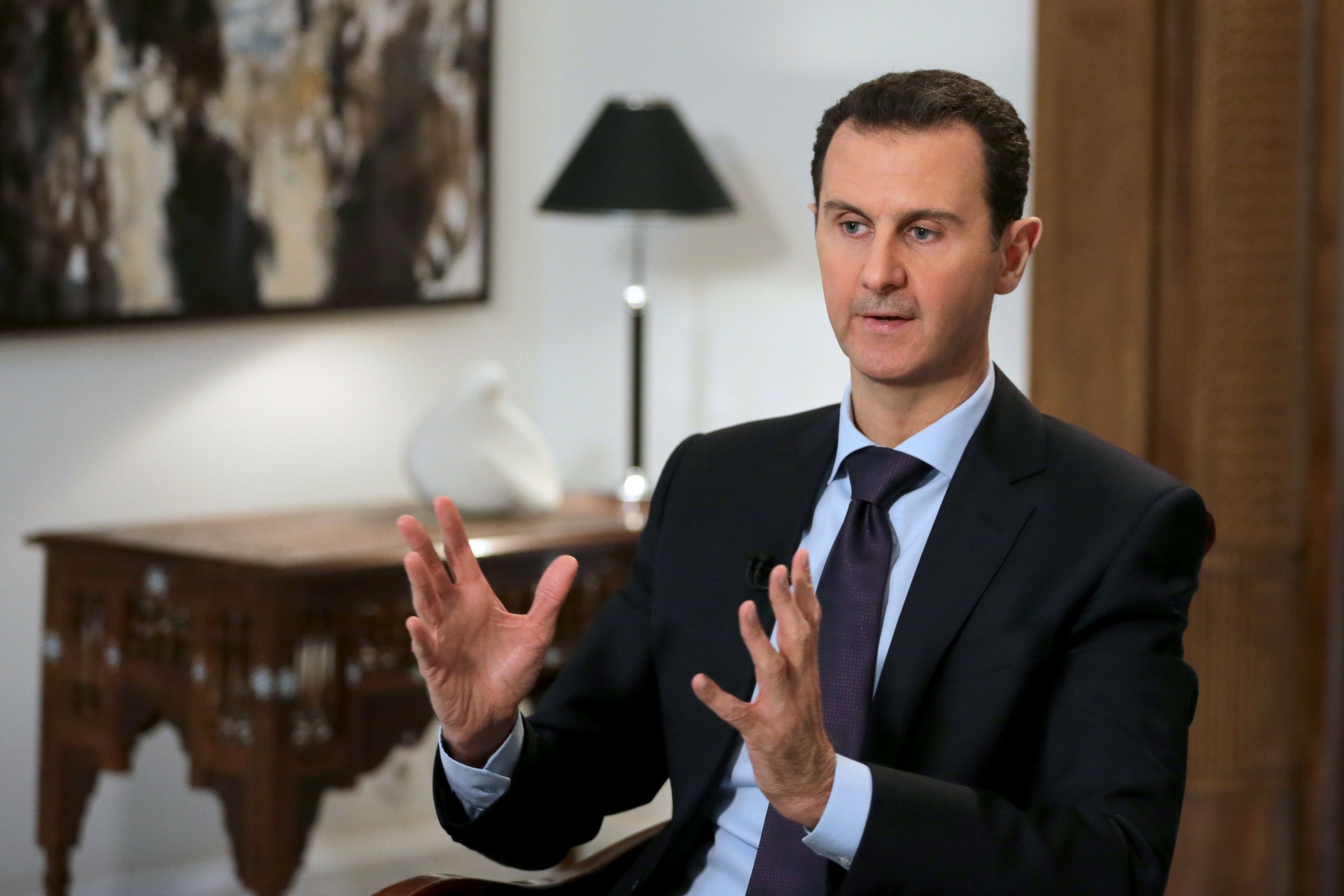

When nearly 60 lethal Tomahawk missiles flewi nto Syria last week, the United States asserted that the strike was necessary and legal due to our certain knowledge that Bashar al-Assad’s government planned and executed the chemical strike. A chorus of nations, led by Russia and Iran, point out our credibility deficit stemming from the Iraqi WMD debacle in 2003 to the Trump Administration’s questionable wire-tapping allegations. The White House subsequently accused Russia of trying to obscure the Syrian government’s role in the attacks — culpability that Assad himself now claims is “100% fabrication.”

Welcome to the post-truth, alternative-fact world of international relations, where a president’s own manipulation of the truth comes home to roost. How did we get to this point, and what can we do about it?

US credibility globally has always been questioned before, to be sure, most recently in a serious way after the WMD mistakes we made in regard to Iraq prior to invading that country in 2003 – this was the beginning of a steep decline in US credibility. And throughout diplomatic history, nations have often sought to undermine the credibility of their opponents for political purposes going back to the ancient Greeks and Persians. But we have arrived today at a point when our credibility feels unusually low, which will create real drag on our ability to build coalitions, convince allies and partners to come along on our missions, and convince the neutral nations of the world that we are in the right.

The political campaign of 2016, full of mud-slinging, name-calling, and FBI investigations of both parties heightened this. But what has hurt the most is the tendency of the Trump Administration to play it loosely with facts, to say the least, from crowd size to complete success in Yemen to Obama wiretapping.

Cut to the strikes in Syria, which were legal, proportional, and a sensible response to Assad’s flagrant use of chemical weapons. Unfortunately, they are seen in certain parts of the globe through the dark lens created by months of what might charitably be described as confusion and misstatements, but what many observers have now branded as “alternative facts.” This hits the Administration in the three principal audiences for the strategic signal represented by the strikes: the people of the United States, who already suffer from a bad case of “Middle East fatigue;” our friends around the world, upon whom we will depend to build a coalition to ultimately bring down Assad; and our enemies, who are spring-loaded to disbelieve us anyway. In all three strategic communications target zones, our shredded credibility is insufficient to create real belief. And here’s the key: in the end, deterrence is the result of capability (which we demonstrably possess) and credibility, which is so badly damaged. Can we recover?

Given the circumstances, we have to begin by simply following a more virtuous path in terms of public pronouncements, speeches, and other strategic communications from the US government. This means not just the White House but all of our cabinet agencies must be scrupulous in fact-checking themselves, reporting only verifiable facts, and responding to media requests with hard truth. And yes that includes tweets from the top.

Second, we need to redouble our efforts to provide real evidence, especially in controversial situations like the chemical weapon use. It will be insufficient for us to simply assert things; instead we need recordings, videos, scientific analyses, testimony from credible witnesses, and high-level intelligence. Naturally we must protect sources and methods, but frankly if we are going to rebuild our credibility we will need to bring our best evidence to the table.

Third, we must work with our allies and friends to create a coherent campaign plan of strategic communications that builds on our words with their support. We need to make our pronouncements in alignment with other credible actors, creating a kind of international chorus of truth.

A fourth powerful voice would be media and non-governmental organizations. Bringing them more into the tent, so to speak, addressing their skepticism and questions with respect and facts instead of yelling at them to “stop shaking their heads” would go a long way toward helping.

As Rick Warren, ethicist and pastor said, “The most essential quality for leadership is not perfection, but credibility. People must be able to believe you.” We have work to do.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- TIME’s Top 10 Photos of 2024

- Why Gen Z Is Drinking Less

- The Best Movies About Cooking

- Why Is Anxiety Worse at Night?

- A Head-to-Toe Guide to Treating Dry Skin

- Why Street Cats Are Taking Over Urban Neighborhoods

- Column: Jimmy Carter’s Global Legacy Was Moral Clarity

Contact us at letters@time.com