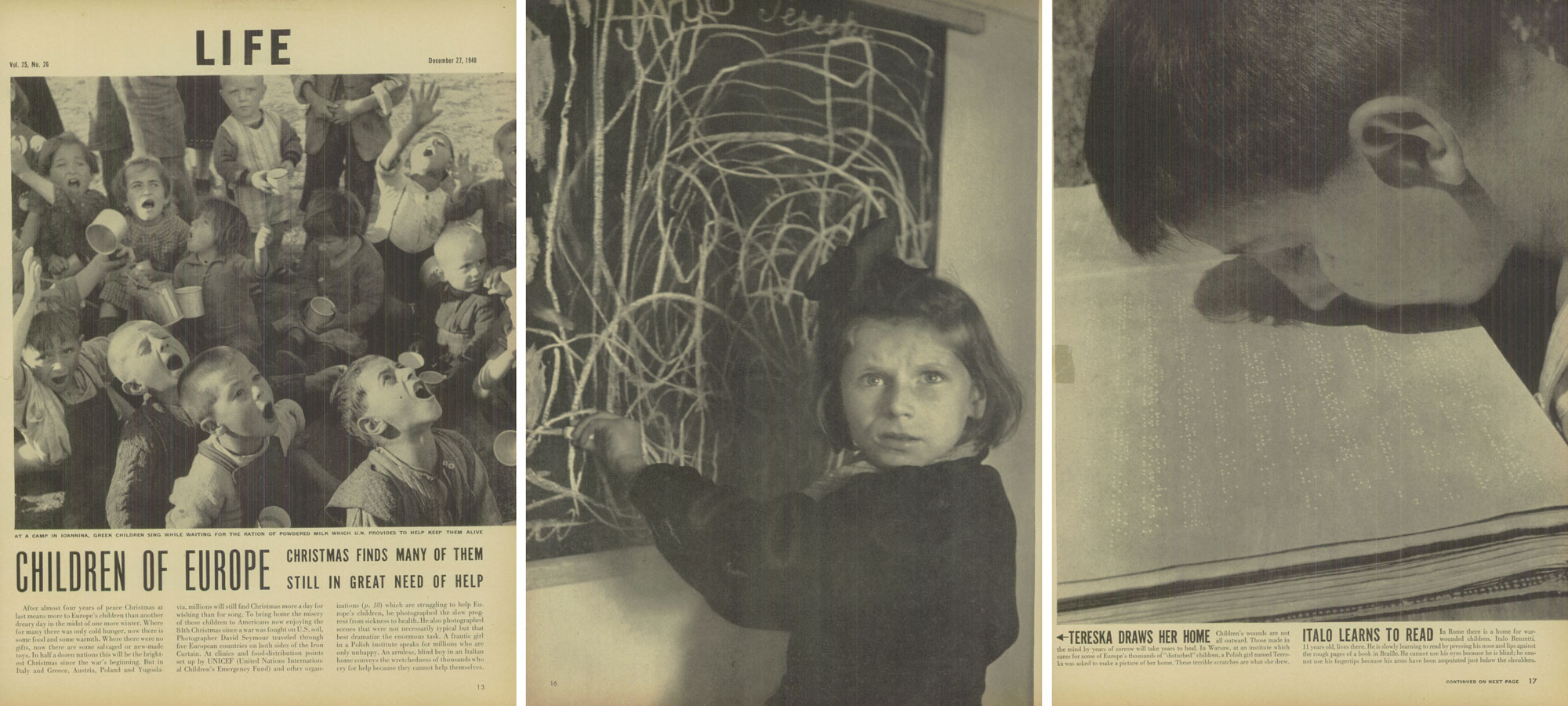

An extraordinary picture taken in 1948 by David ‘Chim’ Seymour, one of Magnum Photos’ co-founders, has since been seen by millions: first, it was published in LIFE magazine where the caption read in part “Children’s wounds are not all outward. Those made in the mind by years of sorrow will take years to heal.” Then it was selected by Edward Steichen for his legendary exhibition The Family of Man. This image of Tereska drawing her home has fascinated many and has become emblematic of World War II.

In the Spring of 1948, when Chim was sent by UNICEF as a special correspondent to report on children in five European countries, 13 million children of Europe had survived World War II. They were homeless and orphans, many of them physically wounded as well as mentally traumatized. As a new retrospective of Chim’s photographs opens in Israel at Tel Aviv’s Beit Hatfutsot Museum, it seems like a perfect time in history to take a new look at Tereska’s picture.

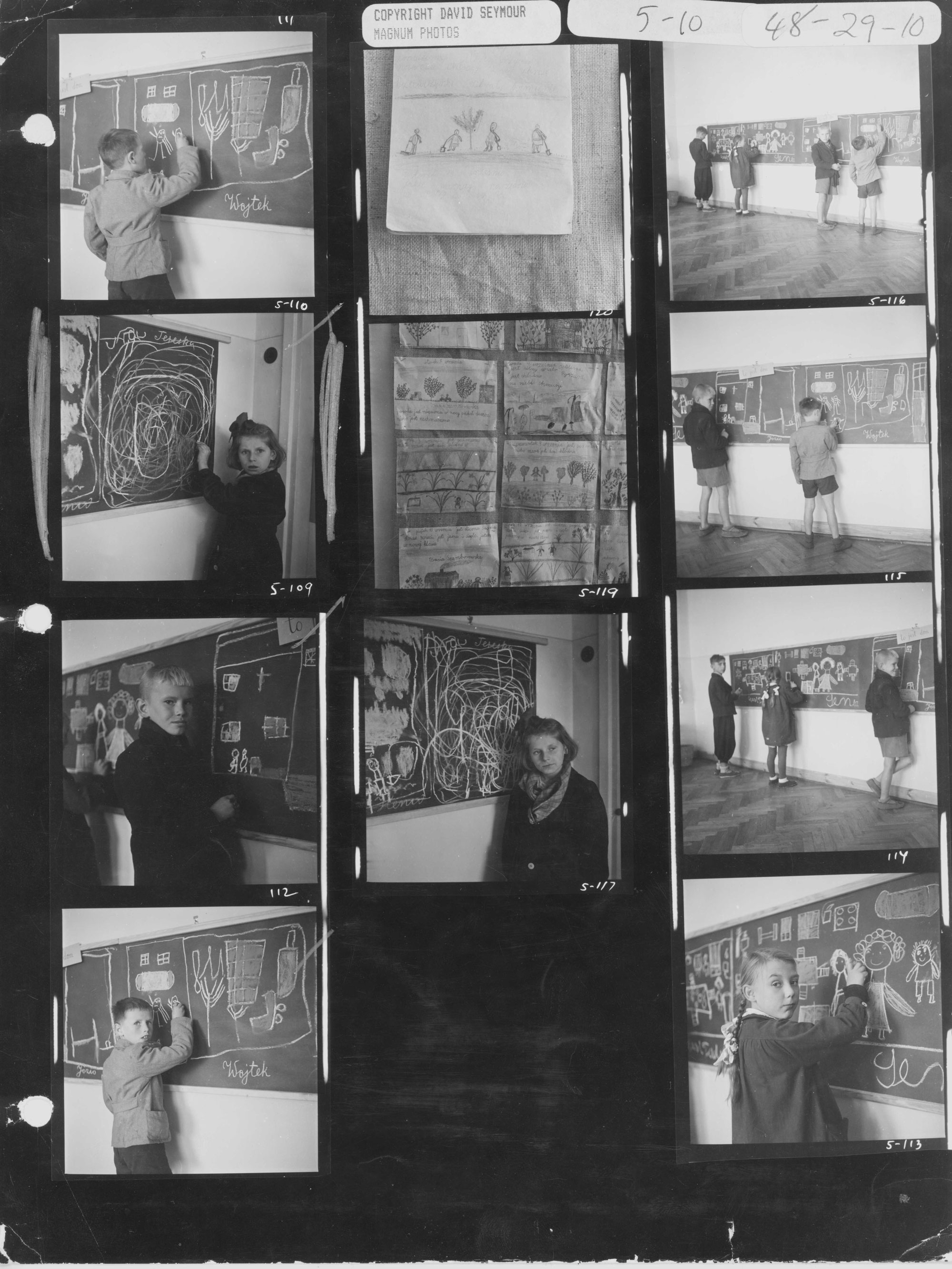

In a school for “backward and psychologically upset children,” as Chim states in his story’s captions, Tereska, then seven or eight years old, is standing in front of a blackboard. As we see in Chim’s contact sheets from a pinned notice on the blackboard, the teachers’ assignment was ‘To jest dom”- “This is home”.

That is what children were supposed to draw, but Tereska could only trace in chalk a tangle of frantic lines. Her haunted eyes reflect her confusion and anguish. Tereska’s identity has remained a mystery for almost 70 years.

Initiated by Gregor Siebenkotten, director of the Tereska Foundation, a thorough research on Tereska has just been carried by Patryk Grażewicz, a Polish researcher, and Aneta Wawrzyńczak, a human-rights journalist. Matthew Murphy, an editor at Magnum Photos’s New York office and myself assisted them from this end with information on Chim’s life history and archive.

Early in September 1948, Chim arrived in Poland, his native country and the last he visited on his mission (after Italy, Greece, Austria and Hungary). He had found out that his parents and most of his family has been killed by the Nazis.

After traveling to Otwock, 25 miles from the capital, where he summered as a child, he went back to Warsaw, where he photographed the ruins of the Jewish ghetto and children on Stawki Street. They were walking home from their school, the only building that had not been razed during the Warsaw bombings.

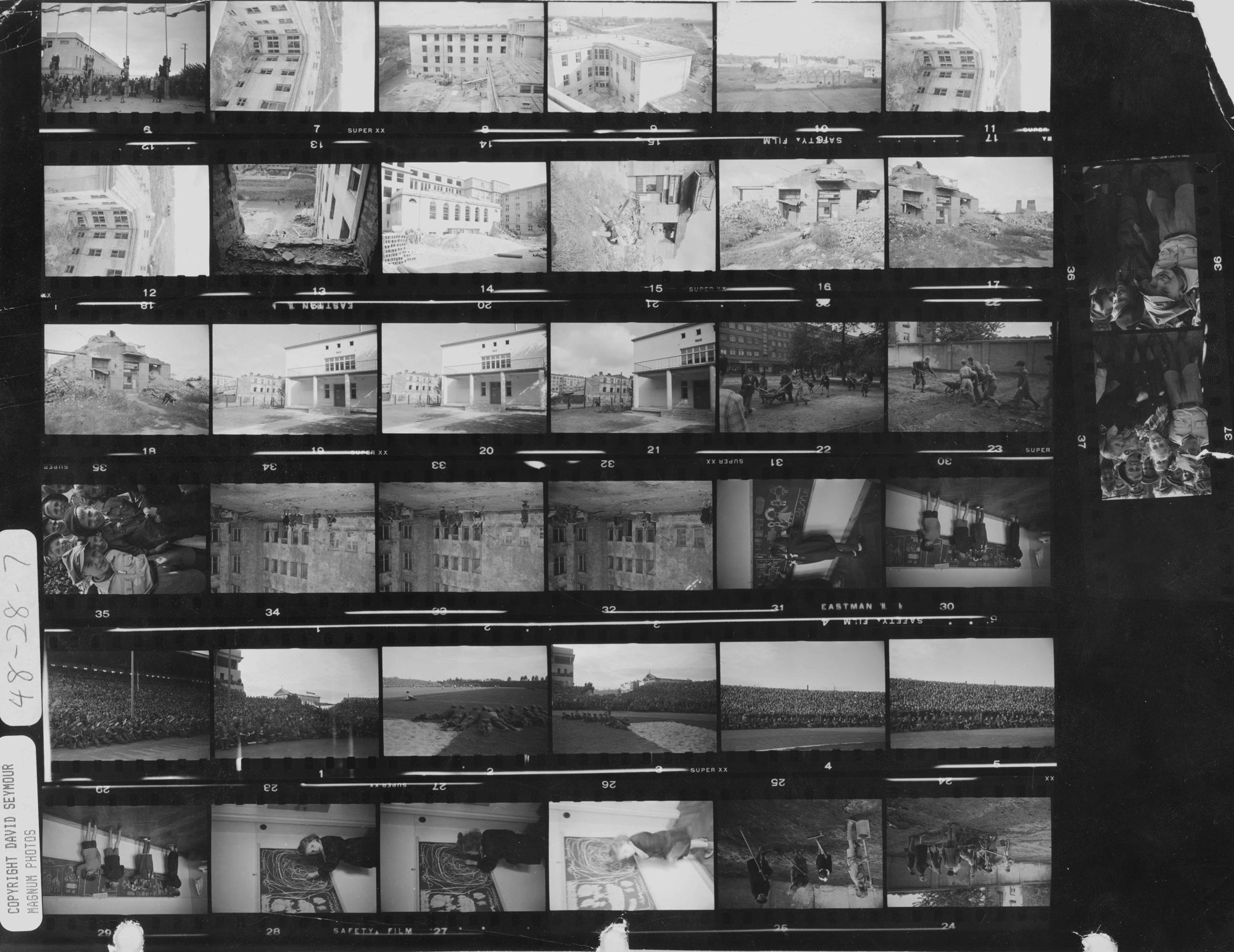

The captions and contact sheets of his story on Polish children, shot with both 35mm and Rolleiflex, let us follow the photographer on a mid-September morning of 1948. Chim first photographed at the Legia Warszawa soccer stadium, then walked among Warsaw’s ruins, shooting on the way. He chanced upon a group of schoolchildren pushing wheelbarrows full of rubble, and he followed them, finding several other children working on their garden plot as occupational therapy. He photographed children from the same school standing in front of a group of buildings.

Thanks to an architectural historian from the non-for profit group Warszawska Identyfikacja, the buildings were identified. Incredibly given the amount of war destruction in Warsaw, one of them was still standing on Okopowa street, in the Muranów district, the former Jewish ghetto.

The next step was to identify Tereska’s school.

The school was the topic of a 1948 short film, where one can recognize in the classroom several elements present in Chim’s photographs: wooden floors, similar wall painting, a black trim painted on the wall, and a big round black metal buzzer placed near the door. It is not longer a special-needs institute but has become Primary School no177 on Tarczynska street, in the Stara Ochota district. The Institute’s archives have been moved to its new location, and the principal there readily granted the researchers access to the 1948-1957 years of the archive, which still hold a few moving notes made by Tereska’s teachers, such as this one: ”She is talkative, keen on schoolwork, and actively contributes to reading and counting classes.”

Three possible “Tereska” were identified from the 1948 class list. One of them was too old to be the girl in the image – she was 12 or 13. When the researchers saw family pictures of the second Tereska, it became obvious that it also wasn’t her. The third Tereska was seven or eight, which tallied with the picture, and had left the school after a year. The research team was able to find her brother and sister-in-law and to piece together a few elements of her life.

Teresa Adwentowska came from a Catholic family. She was one of two daughters of Jan Klemens, who was an activist in the Polish Underground State, the Resistance. During the Warsaw uprising (August-October 1944), he was heavily beaten and all his teeth were broken by the Gestapo at their Warsaw headquarters and prison. During the war, Tereska’s mother Franciszka did her best to make ends meet, for instance visiting the Jewish ghetto in order to trade goods.

During the bombing of Warsaw by the German Lutwaffe, Tereska’s home was destroyed, and her grandmother was most likely shot by Ukrainian soldiers who were helping the Germans annihilate the Warsaw Uprising. Tereska was struck by a piece of shrapnel that left her brain-damaged. Fleeing Warsaw after the bombings, four-year old Tereska and her 14-year-old sister Jadwiga spent three weeks trying to reach a village forty miles away from Warsaw – on foot, in a war-ravaged country. They were starving. That episode left her with an insatiable hunger, and her physical and mental condition steadily deteriorated. During the 1954/1955 school year, she had to be sent to a mental asylum in Świecie (about 190 miles from Warsaw). Since her early childhood she had loved drawing, mainly flowers and animals. As a teenager she got addicted to cigarettes and alcohol, and became violent towards her younger brother. Since the mid-sixties, she spent her life at the Tworki Mental Asylum near Warsaw; the only things that meant anything to her were cigarettes, food and her drawings.

In 1978, at the Tworki Mental Asylum, Teresa Adwentowska met with a tragic death: she accidentally choked on a piece of sausage that she had stolen from another patient.

Chim’s photograph of Tereska, which has become a symbol of the fate of children during war and has inspired the Tereska Foundation, remains one of the only portraits of her as a child. As if caught in the tangled web of her own chalk lines, she remained frozen in time: for Tereska, war never ended.

Carole Naggar is a photography historian and poet.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com