It has been more than 50 years since the 1963 publication of James Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time, a New Yorker essay that in its book form turned into a career-defining assessment of American life, but the author has recently been the subject of a spate of posthumous interest. As the subject of an Oscar-nominated documentary and the thematic inspiration for Ta-Nehisi Coates’ Between the World and Me, Baldwin has again and again proved his continued relevance over the last few years.

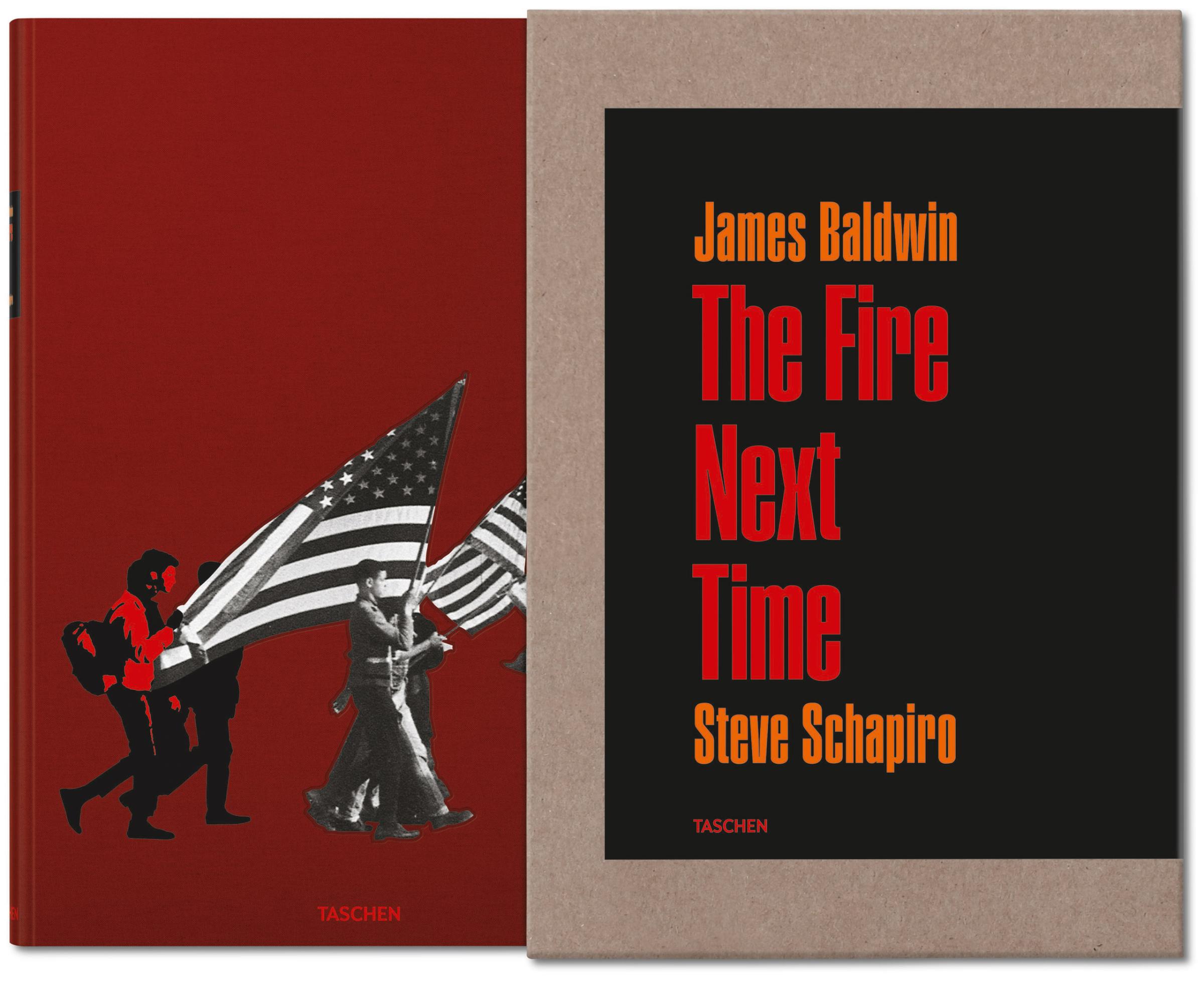

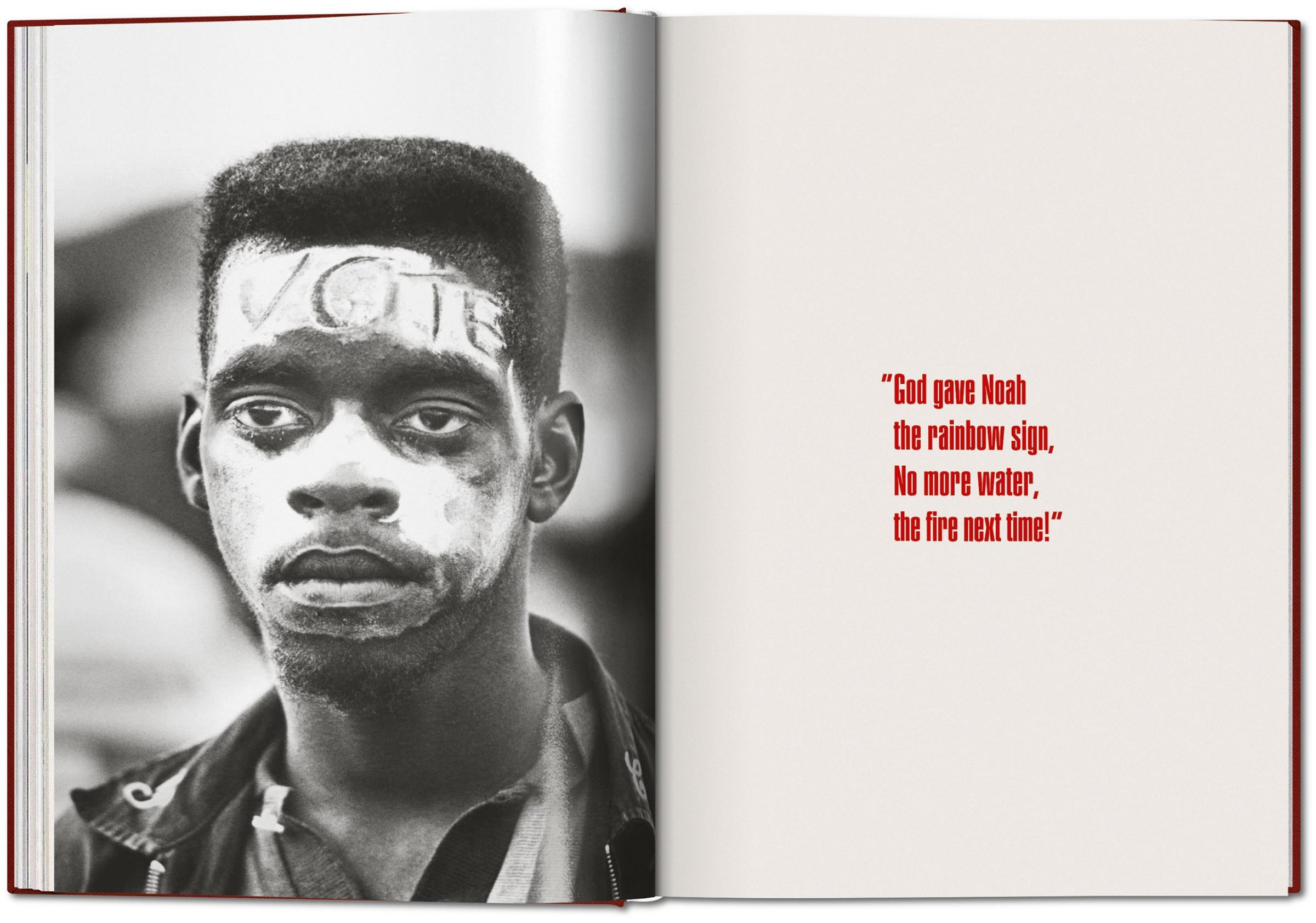

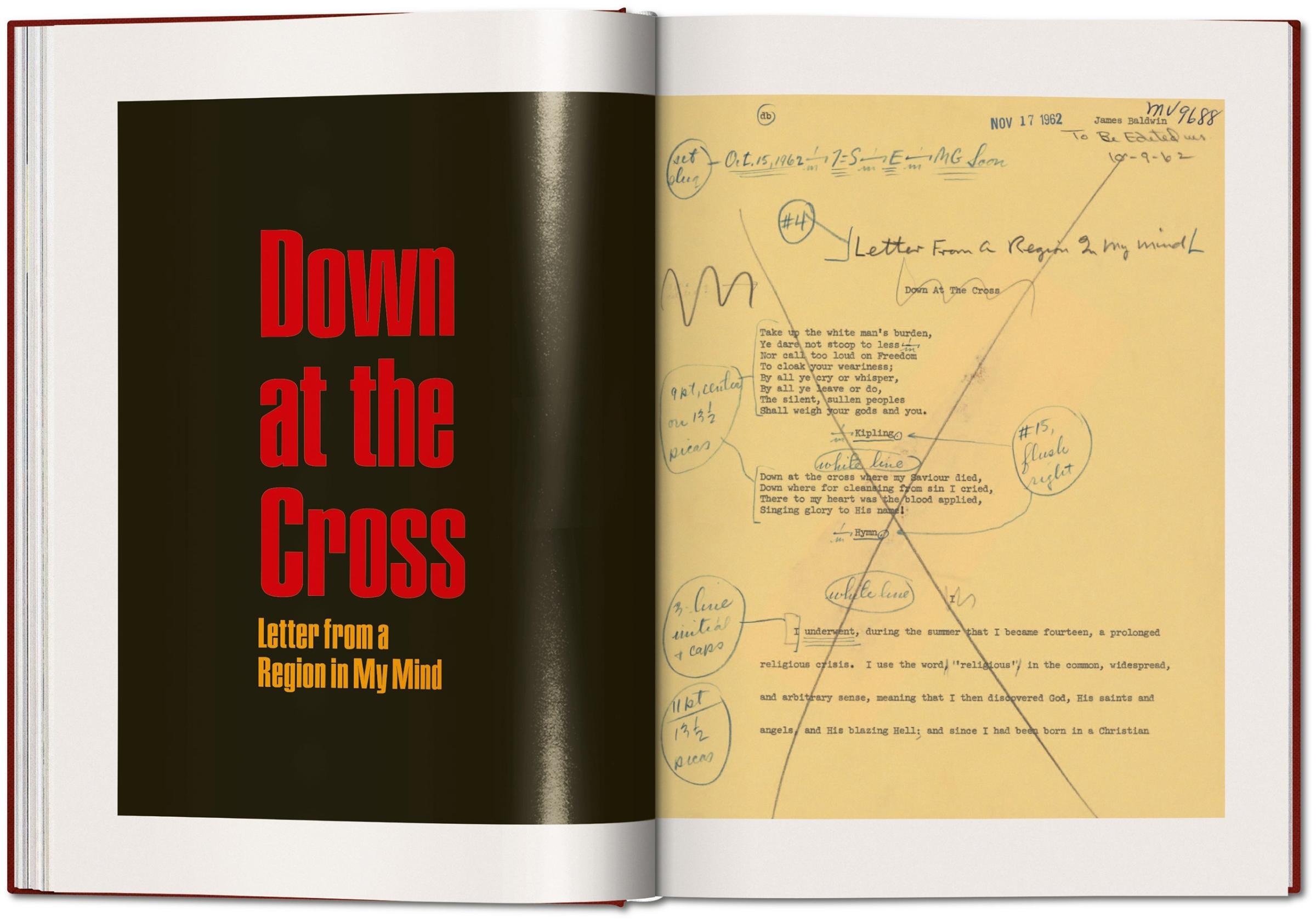

Now, a new Taschen edition of The Fire Next Time pairs the seminal text with photographs by Steve Schapiro, including some images that have never been published before.

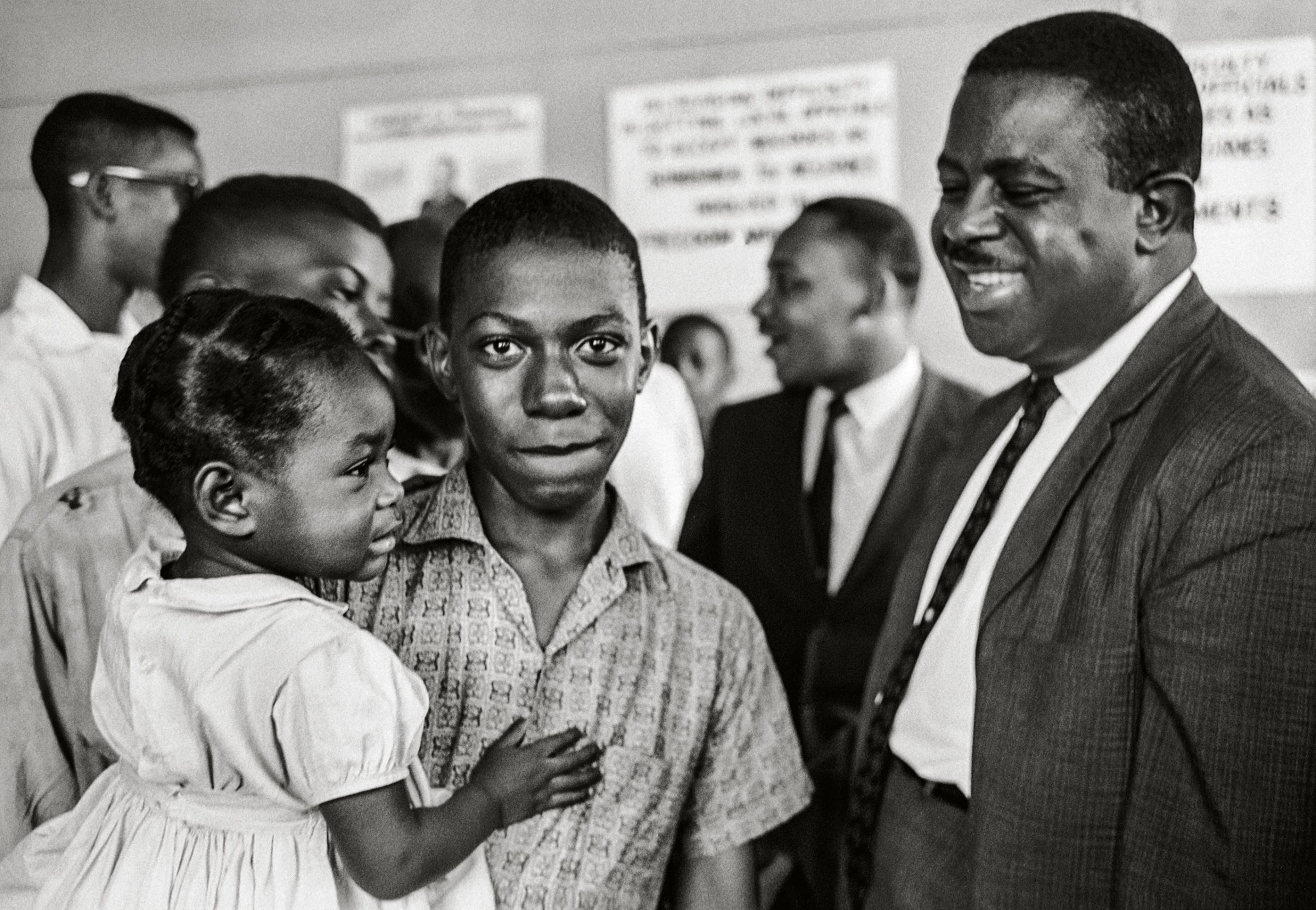

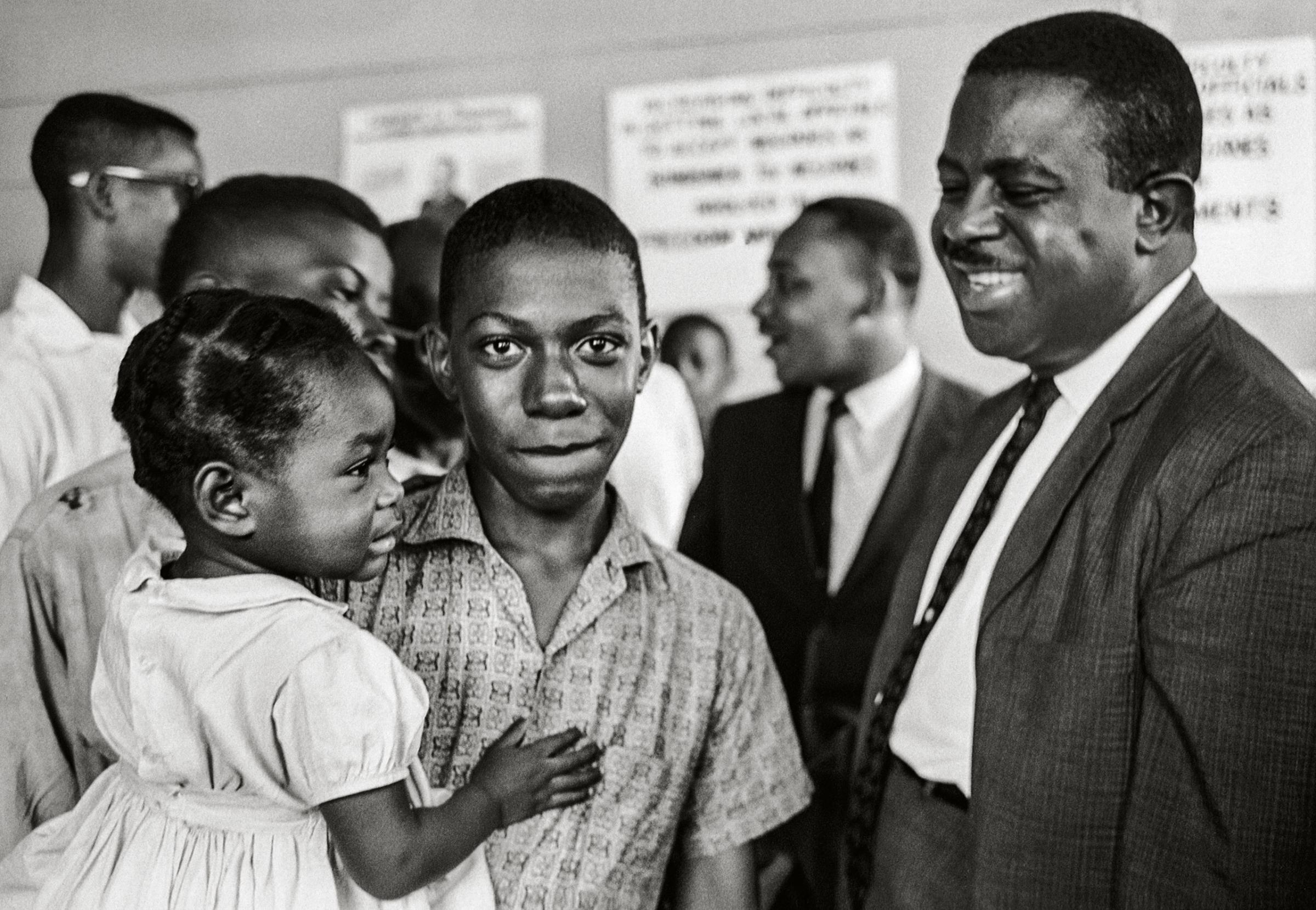

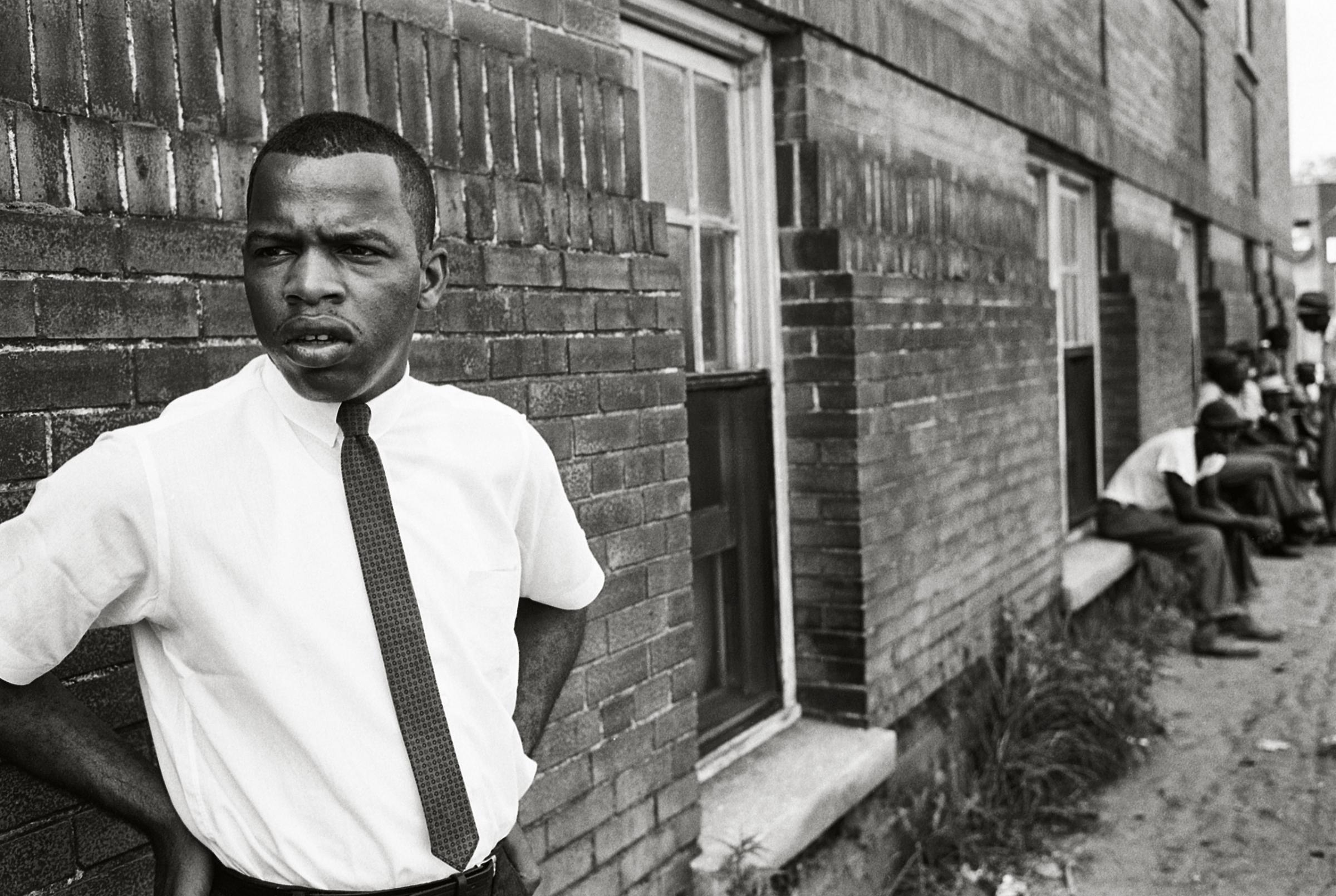

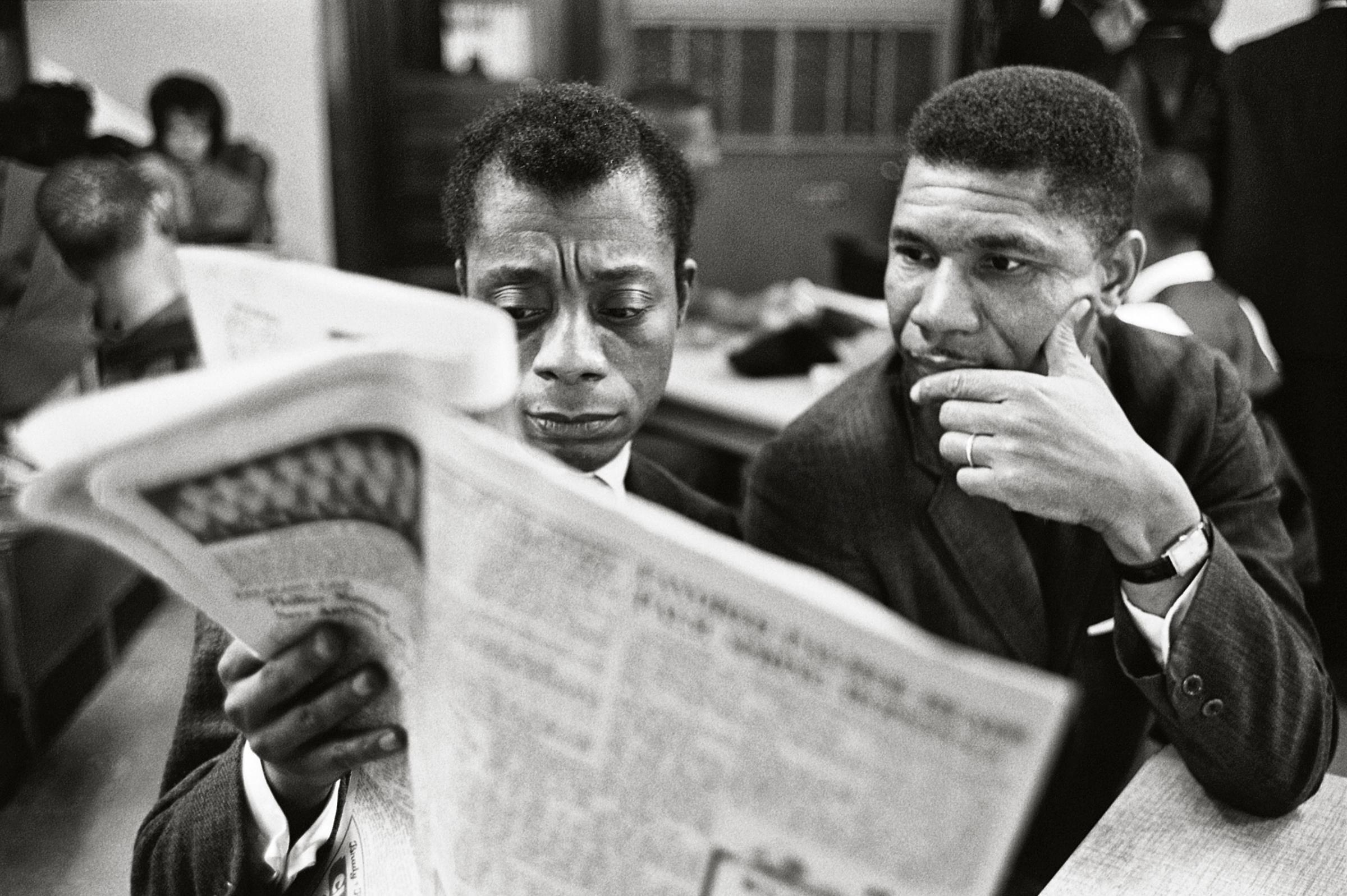

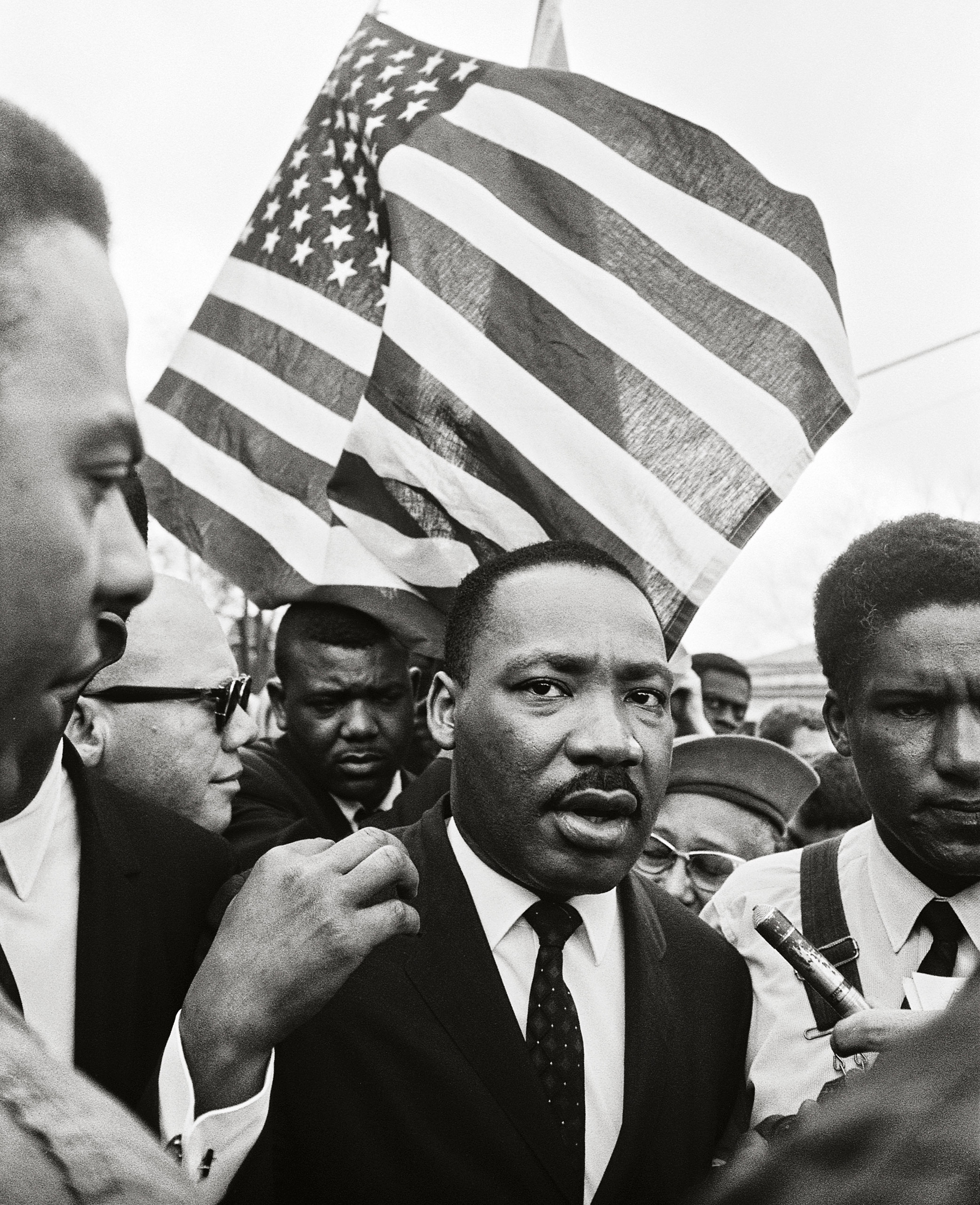

Schapiro and Baldwin had a long history together. In 1963, Baldwin was the subject of a multi-page story in LIFE Magazine with photographs by Schapiro, who traveled from New York City to the American South with the author. As the resulting story, with text by Jane Howard, explained, the book’s release had changed Baldwin’s life but he was proving up to the task he then faced:

“I’ve been here 350 years but you’ve never seen me,” said the frail, gnomelike Negro of 38. James Baldwin spoke from a New Orleans church pulpit but he was talking to a lay audience, mostly white, and he was giving them hell. He spoke both as one Negro and as his race’s voice against the rigid attitudes of white men’s fears and judgments: “I represent sin, love, death, sex, hell, terror and other things too frightening for you to recognize.”

This was a new role for Baldwin, whose main occupation has been writing probing novels (Go Tell It on the Mountain, Giovanni’s Room, Another Country) and articulate, somewhat specialized essays on the Negro in America. For 10 years his novels sold well, his essays were accorded respectful criticism, and Baldwin swam around fairly anonymously in the intellectual fishbowls of New York and Paris.

Then early this year a searing essay he wrote for The New Yorker was combined with a gentle letter to one of his nephews, and became a bestselling book called The Fire Next Time. So intuitively does it dissect the nation’s explosive race problem that Baldwin found himself a celebrity overnight. He also, reluctantly but doggedly, found himself on a whistle-stop speaking tour.

That Baldwin took naturally to his role didn’t mean he was glad to take it on. His existence as a public figure got in the way of his life as a writer, and he found himself having to respond to people — well-meaning white liberals, in particular — who saw his celebrity as a reason to believe he had nothing to complain about anymore.

Schapiro’s photographs of the civil-rights movement are a reminder of just how much that perspective missed the point. Baldwin may have been personally insulated by wealth and fame and talent, but his people were still oppressed and his responsibility to express that oppression only grew as he moved toward his goal of being a great artist — not just, he reminded the magazine, a good one.

“An artist is a sort of emotional or spiritual historian,” Baldwin told LIFE. “His role is to make you realize the doom and glory of knowing who you are and what you are.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com