Dr. Goel is a physician and recipient of the Cannes Lion for his work in human rights advocacy

In the past month, nearly every conversation with my family has ended with the same two words: “Be safe.” As Indian Americans, we and so many like us today feel unsafe in the most basic day-to-day aspects of our daily lives: pulling into our driveways, walking across our front lawns or while getting a drink after work. Innumerable immigrants, like my parents, have dedicated their lives to America, only to now be disrobed of security in the very communities they have long served. Yet, with nativist fears simmering, this hatred hurts more than just immigrants. It also endangers the health care of many more at-risk Americans.

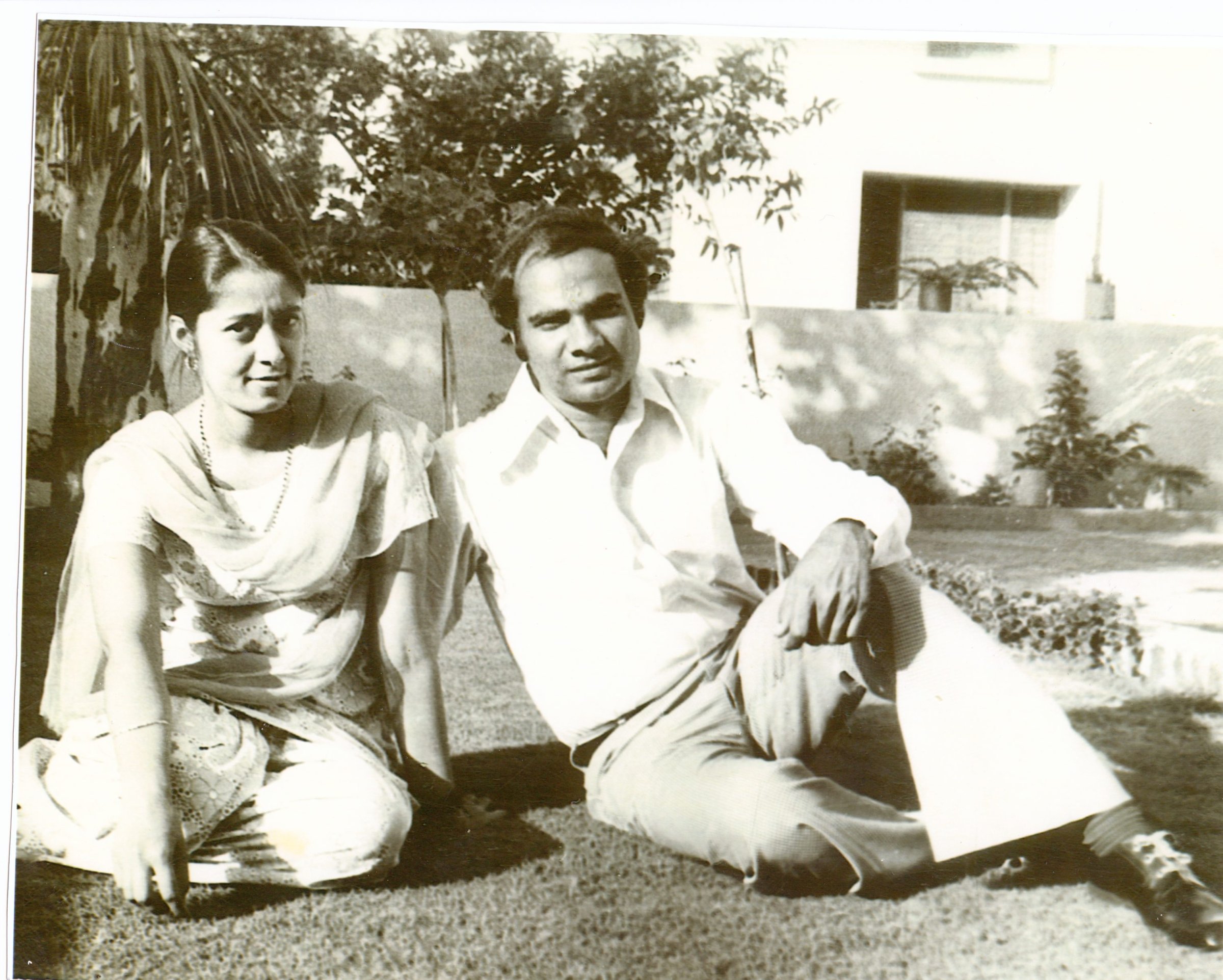

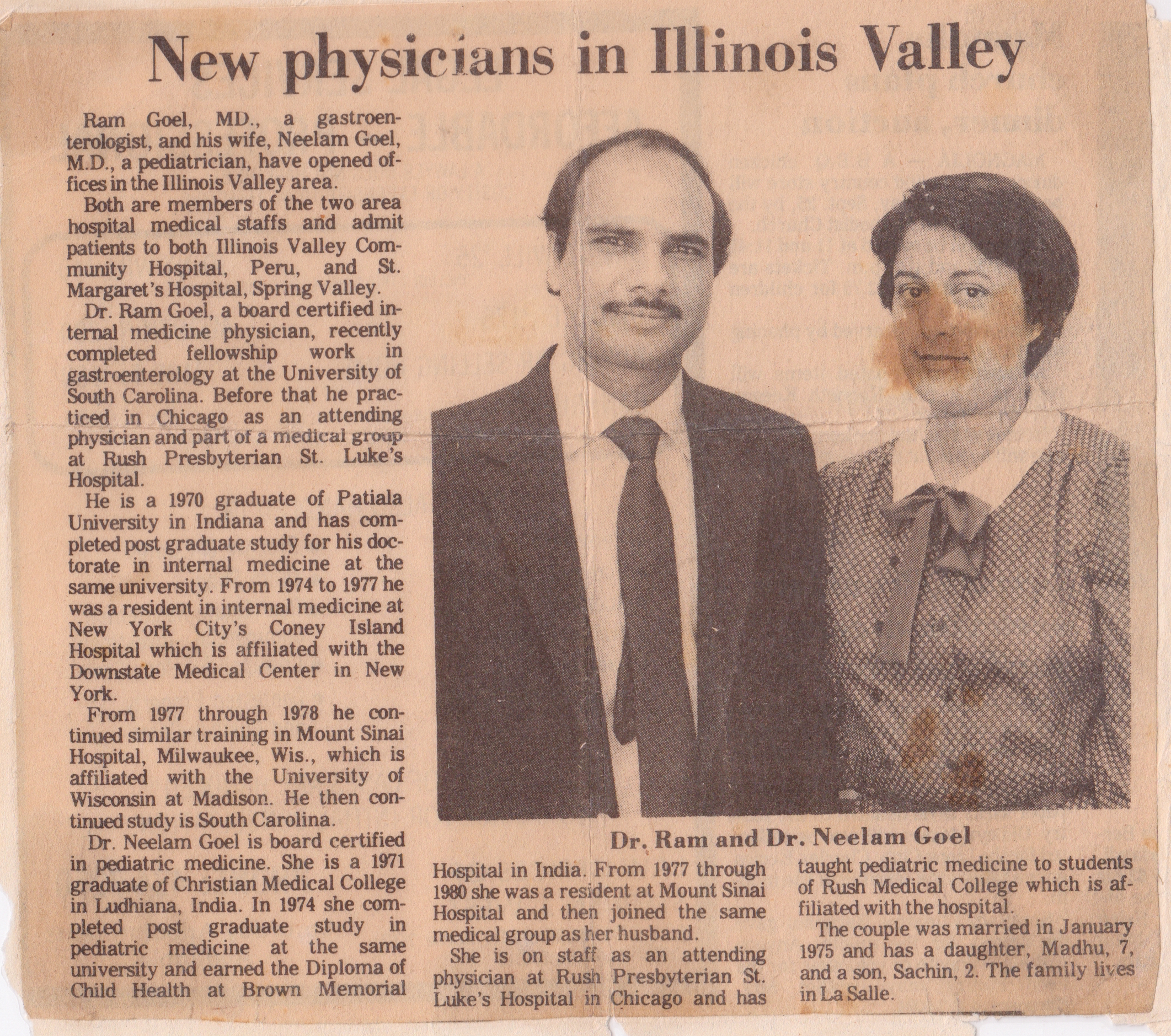

My parents entered the United States during an immigration surge of highly trained professionals and a time of physician shortages in America. It was an unlikely story, as my father was born to a family of sugar cane farmers in rural India. He was the youngest of nine siblings and the only one to have finished schooling beyond a primary education. After receiving the highest exam scores in the entire state of Punjab, he received a full scholarship to medical school, after which he completed his post-graduate training in internal medicine. He soon met and married my mother, a gifted pediatrician also from Northern India.

In 1974, they left India for America and arrived in arguably the most American of places — Coney Island, Brooklyn — with $12. As international medical graduates, they repeated their post-graduate training in America in order to sit for the U.S. licensing exams, which amounted to an additional ten years of training.

When my parents finished their training, my hometown of Peru, Illinois, like vast swaths of rural America, needed doctors. They settled in and set up practices. Peru had roughly 10,000 inhabitants when I grew up, and over the next 35 years, my family came to know almost all of them. My mother was often the first person to hold and take care of the town’s children. My father took care of the town’s parents and grandparents. Growing up, I often heard stories of lives saved and years lived healthier and more full because of my immigrant parents. Today, my dad is 70 years old and is still one of the few doctors on-call 24/7 for the town’s medical emergencies.

My family’s narrative is not unique, but rather reflects a shared story. According to the Migration Policy Institute, over a quarter of physicians across the United States are foreign-born — many staffed in America’s Rust Belt and the Deep South, places that oftentimes U.S.-born doctors don’t go. And there is a real concern that this hostility toward immigrants will have potentially devastating consequences on the health of these very communities across the heartland. There are stories like that of Dr. Ali Fadhil, an Iraqi translator for Americans during the war, who had to recently move his family from rural Georgia, where he was practicing as a physician, to California after concerns for his family’s safety and wellbeing. This downward spiral of consequences will only further stress the fault lines of rural communities, leading to even further divide and continental drift.

The recent executive orders on immigration added insult to injury as the physician shortages that brought my parents to this country persist to this day. According to a 2016 report from the Association of American Medical Colleges, there is an estimated shortage of 8,200 physicians in America; the organization projects that number to swell as high as 94,700 by 2025. Over half of the over 7,000 new doctors trained in internal medicine across the country are international medical graduates, many from Muslim-majority countries including Syria and Iran.

In order to train in the United States, international graduates apply for J-1 visas, which explicitly require two-year commitments of post-training service to be allowed to subsequently stay in the U.S. These commitments secure foreign-born doctors for some of the most underserved areas and vulnerable populations in America. If the recent executive orders on immigration withstand court challenges, Native Americans, veterans and children in remote rural areas and inner cities alike are at risk of losing much-needed medical staffing as these positions go unfilled.

As a child, I came to believe that America was not only home, but it was also a promise. A promise of tolerance and religious freedom. A promise of a ladder for those willing to climb. A promise that despite our inevitable flaws, we would not yield in our pursuit of a more perfect union. Given our nation’s current tenor however, I cannot help but feel disheartened and even delegitimized in an environment that is hostile towards economic migrants and asylum seekers, escaping our same shared and troubled past — fleeing some of the very same persecutions we now feel in our own five-digit zip codes. Today, I fear that for the first time in my life that the hope and vision America once represented is being questioned, if not overtly threatened. We have replaced reason with irrational fear, and empathy with misdirected anger.

Our immigration system is indeed broken. Too many people live in the shadows. But to blame immigrants for making us less safe or for not belonging is not only uninformed, it’s un-American. As we work to fix immigration, in the midst of the deportations and executive orders that impact highly trained doctors and nurses on which our most vulnerable communities rely, we should strive to be thoughtful and measured, to respect the innate dignity and humanity of all those affected — including the health of the rural communities we’re meant to protect. In the end, we all are the tired, poor and huddled masses. The only thing greater than America is the idea and promise of an inclusive America. For that, we cannot yield in this pursuit of a more perfect union, as the health of our nation depends on it.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Introducing the 2024 TIME100 Next

- The Reinvention of J.D. Vance

- How to Survive Election Season Without Losing Your Mind

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Scams

- Did the Pandemic Break Our Brains?

- The Many Lives of Jack Antonoff

- 33 True Crime Documentaries That Shaped the Genre

- Why Gut Health Issues Are More Common in Women

Contact us at letters@time.com