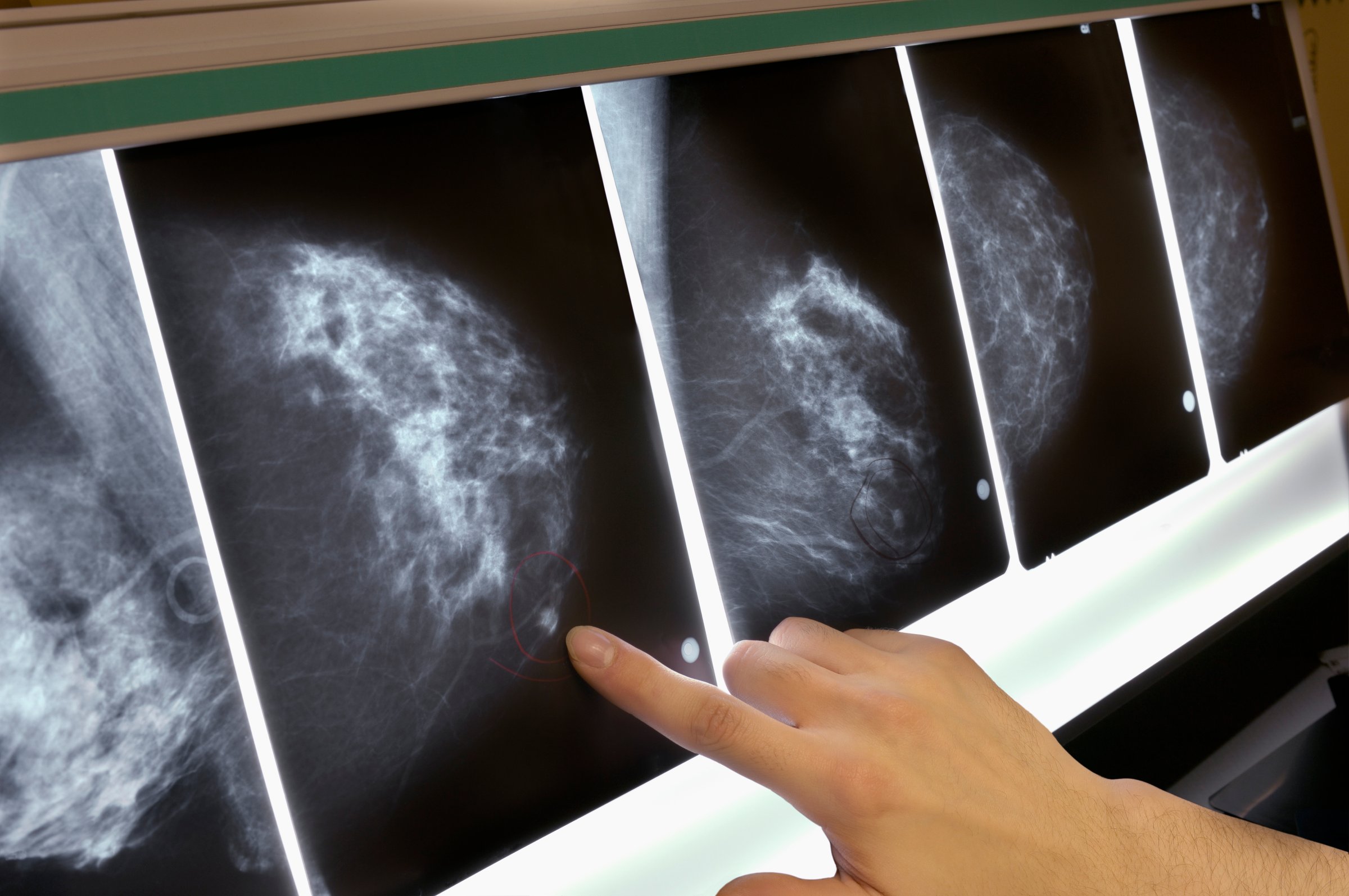

Who needs a mammogram—and when? These are questions that have vexed women for years now as science—and the recommendations it informs—has shifted. In 2009, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) advised that most women should start getting regular mammograms at age 50, rather than at age 40, prompting some groups to change their official guidelines, even as others kept their advice the same.

Today, confusion persists—and women may not be getting much clarity at the doctor’s office, either. In a new study published in JAMA Internal Medicine, researchers found that 81% of the doctors recommended mammography to women aged 40 to 44 and 88% recommended it to women aged 45 to 49 years—advice that goes against the latest federal recommendations.

Dr. Archana Radhakrishnan, clinical research fellow in internal medicine at Johns Hopkins University, and her colleagues analyzed data from 2,000 doctors in the Breast Cancer Social Networks study, a national survey of primary care, internal medicine and family medicine physicians and gynecologists. They found that gynecologists were more likely than other physicians to recommend screening for women in their 40s — their professional physicians organization is one that continues advising women to get screened starting in their 40s.

Ironically, 23% said they trusted the USPSTF guidelines more than other breast-cancer screening recommendations. “Doctors reported trusting a particular guideline, but then recommended screening more frequently than the guideline,” says Radhakrishnan. “What that highlights is that we still have a ways to go to understand what challenges doctors are facing when they implement clinical guidelines into practice.” Those factors may include things like malpractice fears, if they don’t recommend screening and breast cancer is missed, she says.

The disconnect may also reflect a bigger challenge in dismantling a long-standing conventional wisdom, even when such a change is supported by science. For decades, the response to cancer was that more is better — more screening means more cancer can be detected, and therefore treated, earlier.

But recent reviews of the studies show that with breast cancer, more screening does not, in fact, save lives. What’s more, doctors and patients also have to weigh the risks of false positives, the harms that can come with over-treatment, not to mention the psychological stress and anxiety of a positive mammogram. Understanding that not all cancer needs to be treated immediately, but that some cancers can be monitored until they need treatment, is another major change that not all doctors are comfortable with yet.

The findings point out that while the recommendations about breast cancer screening continue to evolve, so too do doctors’, and patients’ decisions about screening. For now, most health groups are learning toward a more personalized approach, encouraging a discussion between women and their doctors about how much screening is right for them.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com