No matter how hungry you are, you’d be very unlikely to sit down to a piping hot bowl of Larry—or anyone else, for that matter. In other words, you wouldn’t eat another person.

Cannibalism has existed throughout the long, strange arc of human history, but even on those occasions when it’s been justified—when the Donner party had a dinner party, say—we don’t much like to think about it. Anthropologists, however, find the topic of cannibalism irresistible. The part that intrigues them most is the why: What situations would impel otherwise sociable humans to turn Stu into stew, or Frank into furter?

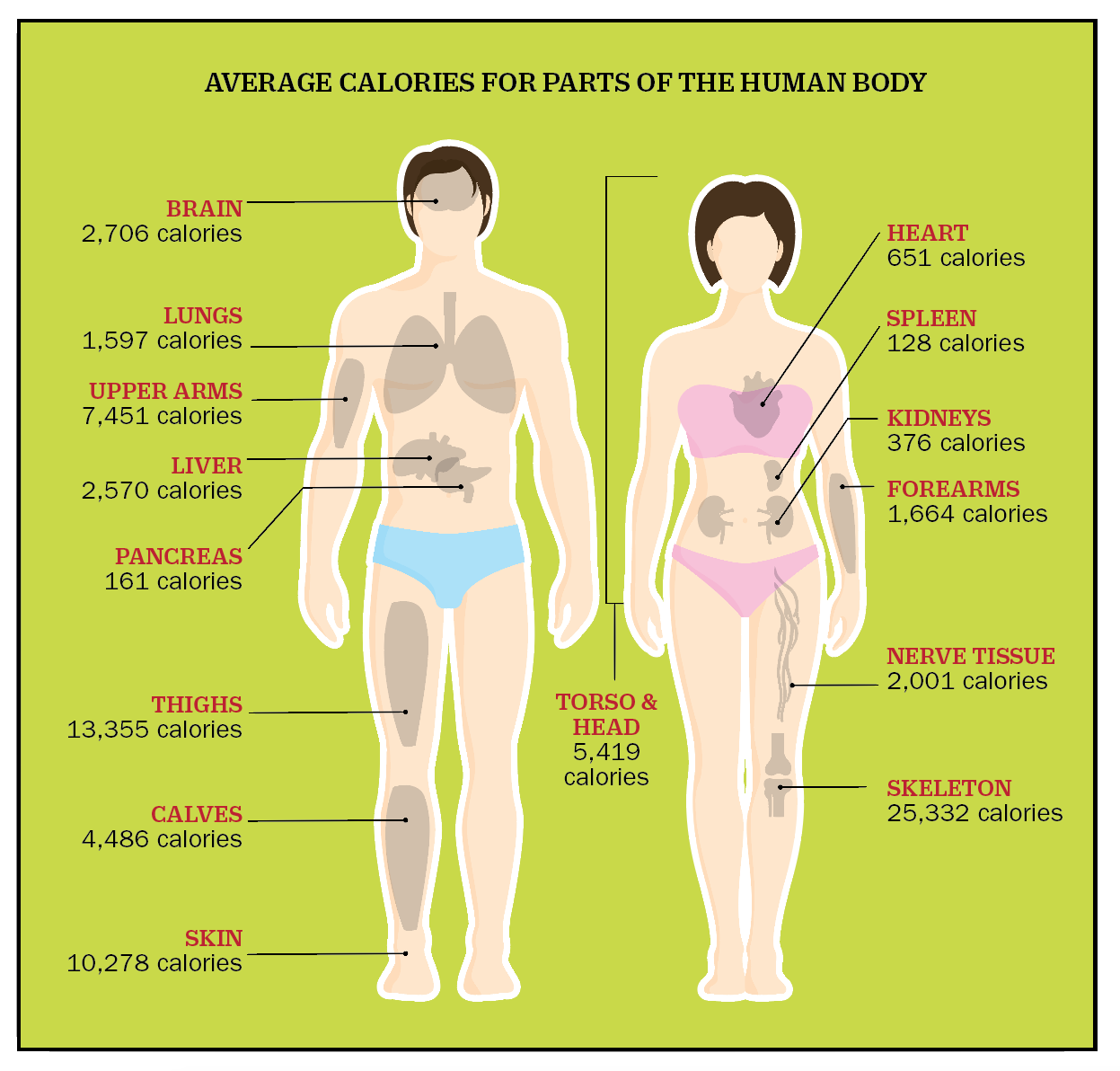

Now, James Cole, a senior lecturer in archaeology at the University of Brighton, may have an answer. In a new study published in Nature, Cole calculates the calorie content of nearly all edible parts of the human body—from loin to ribs to tender rump—and concludes that when people have eaten people, it usually hasn’t been for the nutrition.

Most incidents of human cannibalism occurred during the Paleolithic period: roughly from 2.5 million to 10,000 years ago, a range that easily includes the first appearance to Homo sapiens. To the untrained eye, human remains are just human remains, and once the flesh is off the bone it’s impossible to determine if it decomposed or was devoured. Archaeologists, however, are experts at spotting the unlovely clues that a body became a meal, including parallel cut marks on bone; the absence of the base of the cranium, which would provide access to the brain; and jagged breakage or scorching of bones, both of which suggest attempts to get at the marrow.

Relying on such anthropological forensics, scientists have discovered a handful of sites of where cannibalism unmistakably took place—many of them across ancient Europe—with as few as five and as many as 30 victims per site. To determine the reason behind the feasts, Cole began by analyzing existing data on the chemical composition of the human body, specifically on an adult, male human body weighing an average of 110 lbs (50 kg). That’s small by modern standards, but not by ancient ones; a single man would contain about 66 lbs (30 kg) of lean muscle mass. But he would be made of more than just his choice cuts; he’d also be stomach, heart, lungs, body fat and all of the offal humans regularly consume when it comes from other species.

Adding that all up, one man would represent a walking grocery cart’s worth of 125,822 calories, 32,376 of which would be lean muscle. The thighs would be among the most nutrient-dense parts, packing in 13,354 calories; the upper arms would provide 7,451 calories; the brain and spinal cord 2,706, the liver 2,569 and the heart just 650.

All of that, however, would not last long—and here is where cannibalism becomes a bad survival strategy. Assuming a minimum daily requirement of 2,400 calories per adult, one anatomically modern human would provide barely half a day’s calorie needs for a tribe of 25. For Neanderthals or for anatomically modern humans living in the Paleolithic era—when daily exertion was greater and calorie needs higher—a single human body would stretch for just a third of a day.

Those slim rations compare miserably with other game that was at large at the time. A primitive cow provided 367,200 calories worth of lean muscle mass alone—ten times more than a human; a bison weighed in 612,000 muscle calories; a woolly rhinoceros offered 1.26 million; and the true prize, a woolly mammoth, meant 3.6 million calories of muscle.

What’s more, a human being who has been designated as dinner usually does not give up easily. “The mental and physical effort to hunt a hominin would presumably be much greater,” Cole wrote in the study, “given the hominins’ ability to fight, run and think their way out of the hunt.” Prey animals, of course, put up a fight too, but not the kind a person can.

If a good meal was not what ancient humans were after when they ate other ancient humans, what was? Cole concedes that the fossil record doesn’t hold many answers. In some cases, a famine or an emergency like the one the Donner party faced might indeed have been at play: meaning cannibalize or die. In others, it could have been ceremonial, as when the brains of relatives were eaten after death. In most cases, however, the reason might have been a primitive form of geopolitics. Then, as now, humans expanded their range by killing, and that leaves a lot of bodies behind.

“It might be that once the kill has happened it would make sense to eat the flesh either as a waste not want not, or perhaps as a warning,” Cole wrote in an email to TIME. “In truth we will never really know the true motivations, and they may be different for each episode.” What happens in the Paleolithic, it seems, stays in the Paleolithic.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Biden Dropped Out

- Ukraine’s Plan to Survive Trump

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Write to Jeffrey Kluger at jeffrey.kluger@time.com