In the movie A Quiet Passion, out in the U.S. on Friday, Cynthia Nixon (Sex and the City) plays the poet Emily Dickinson as a woman facing both limited opportunity — typical for women in 19th century society — and physical ability, as she was plagued with a kidney disease that often left her bedridden.

Jerome Charyn, author of the biography A Loaded Gun: Emily Dickinson for the 21st Century, says the film accurately captures just how much such limitations would have constrained a woman like Dickinson, but also how she stood up to them in her own way.

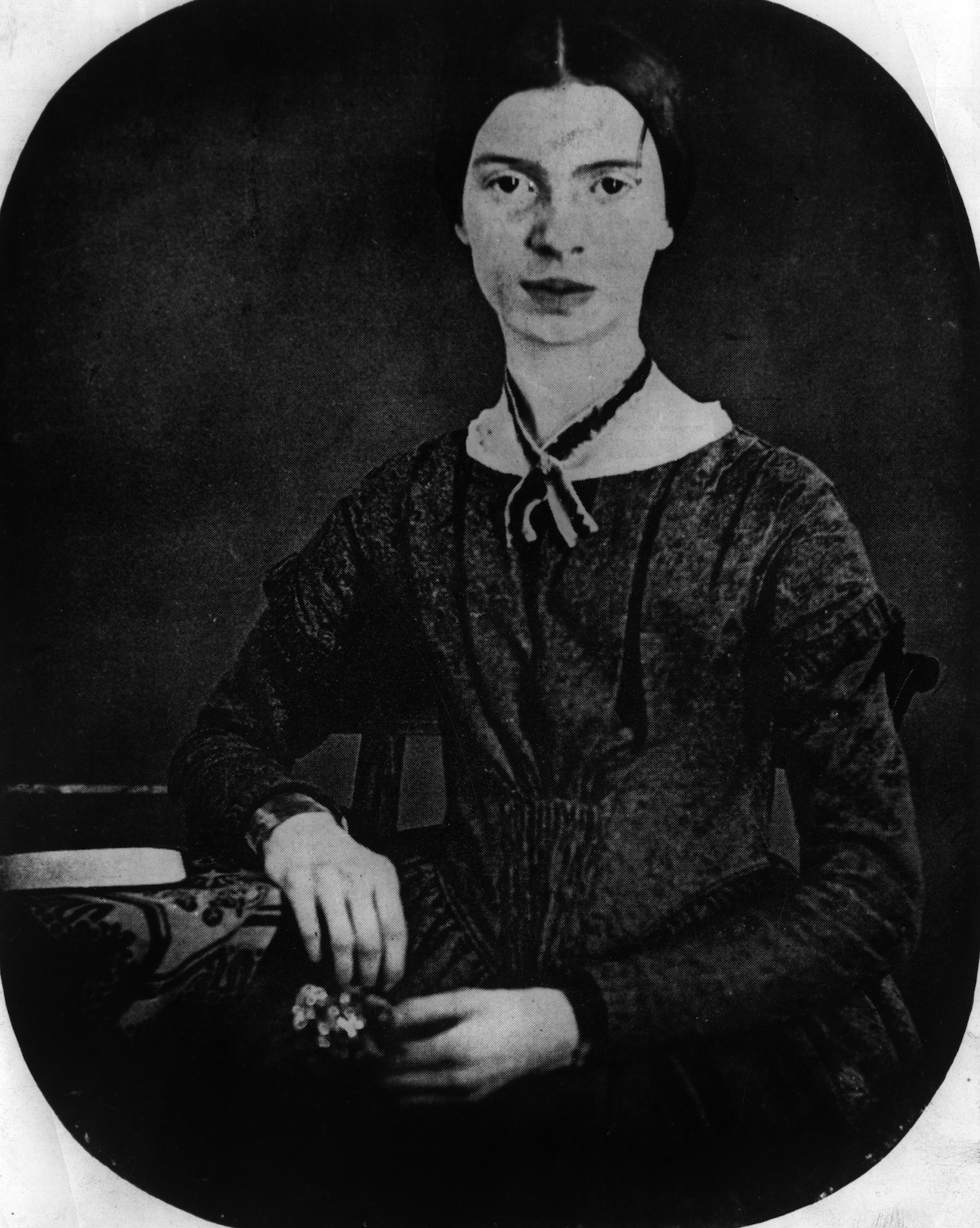

More than a century after her 1886 death, the poet is still known for the quiet, family-centric life she led. She’s usually thought of as “the queen recluse,” as her friend and the publisher of The Springfield Republican Samuel Bowles once described her — generally “a mousey, sickly, tubercular woman who never left her home.” And that depiction is, in its way, true, Charyn says. She often preferred to be at home doing chores, getting up at 5:00 a.m. to start the oven to bake bread and emerging into the outside world just to walk the dog around Amherst, Mass., rather than living for the outside work.

But, within that home, Dickinson could be outspoken too, and Charyn says that the film’s portrayal of her as having a “flirtatious, comical and serious” side is fairly accurate too. For example, one scene in which she smashes a plate when her father says a dish is dirty shows the way she could sometimes be the only member of her family who has the courage to stand up to her father or who is willing to argue with him. And the idea that Dickinson asked him for permission to write poems at night — which he grants, thanking her for asking — is not just about acknowledging the family hierarchy.

“She didn’t have to ask her father’s permission, but she’s also trying to make him aware she’s writing poetry. She wants some kind of recognition,” Charyn argues.

She also wrote about the constraints on women in the 19th century, a topic she knew all too well, as a writer who had to ask her father for money to do anything like buy a pencil, who published anonymously because women didn’t publish under their own names, and who generally had no way of earning a living. When her father died, all of his money went to her brother. “She was a kind of aristocratic pauper,” as Charyn puts it. On top of that, she was seen as an outcast in society for not marrying or having children.

“[The film] makes her very articulate, gives her a kind of lyricism, a deep anger,” says Charyn. “Women didn’t get to present their own ideas in the 19th century, so this is a very new and interesting reading of female power in the 19th century.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Biden Dropped Out

- Ukraine’s Plan to Survive Trump

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com