This post is in partnership with the History News Network, the website that puts the news into historical perspective. The article below was originally published at HNN.

In April 2016, Wyatt Houston Day was expecting a visit from a collector who had made an appointment so that the Swann Galleries’ expert on printed and Manuscript African Americana could take a look at the cartes-de-viste album he owned. The collector had picked this album up at a sidewalk sale at the Puck Building in New York over 30 years before. Some goods left in storage were being sold off, and he bought the collection of photos as a lark. Day was used to disappointment, but when he began to thumb through the album, he recalled: “I almost fell out of my chair!”

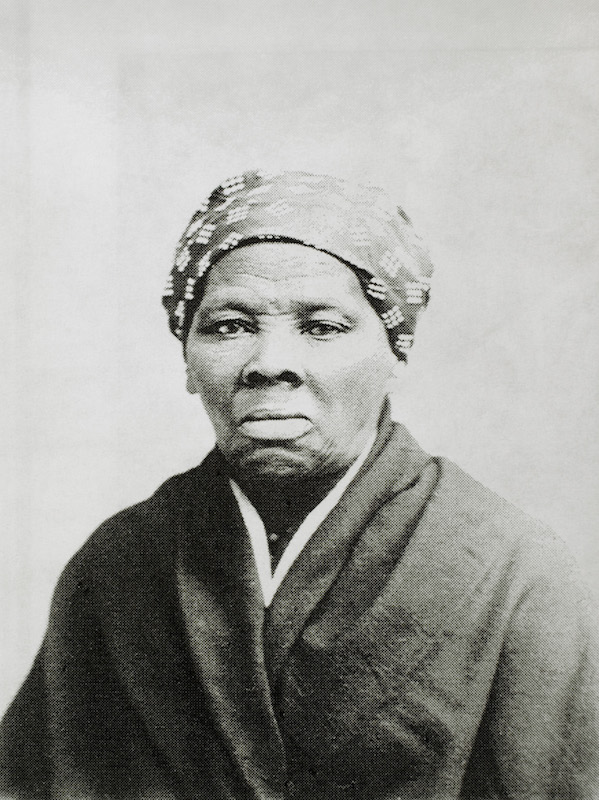

This souvenir album contained 44 19th-century daguerreotypes—men and women, blacks and whites, including a familiar image of the intrepid Underground Railroad conductor, Harriet Tubman. Indeed, this image adorned the cover of not just my own 2004 biography, Harriet Tubman: The Road to Freedom, but also Jean Humez’s book, Harriet Tubman: the Life and Life Stories, which appeared the same year. Our studies, and one by Kate Clifford Larson, were published simultaneously in 2004, nearly 60 years after Earl Conrad’s 1942 biography.

But this souvenir book also contained a previously undiscovered likeness of Harriet Tubman—one Day had never seen before. The esteemed expert had his guess confirmed by scholars that this image was indeed a compelling new portrait of Harriet Tubman.

In the 2015 volume, Picturing Frederick Douglass: An Illustrated Biography of the Nineteenth Century’s Most Photographed American, co-authors Jon Stauffer, Zoe Trodd and Celeste-Marie Bernier provided 160 photographs of its magisterial subject. By contrast, there are fewer than a dozen images of Tubman from her long and productive life as a respected activist who in 1849 escaped slavery in her Maryland birthplace to join the Underground Railroad, to liberate scores of others, shepherding many all the way to Canada.

Harriet’s career before and during the Civil War coincided with the emergence of the daguerreotype and the popularity of the cartes-de-viste. This was a lucky stroke for the UGRR leader, as photographic images became instrumental to the protection of her identity. Because she was illiterate, letters of introduction were not as useful as a picture. It could be a costly mistake if Tubman were to reveal her UGRR connections to anyone but a fellow traveler. Her own collection of photos of UGRR agents and comrades helped to prevent such mishaps. Tubman’s treasured pack of cartes-de viste became her insurance policy. She could show her images to strangers and asked them to name people in the pictures to test their credentials.

Once the Civil War broke out, in essence bringing the underground struggle above ground, Tubman joined the fight—first at Fortress Monroe in Virginia then with regiments in occupied South Carolina, leading Union troops on the infamous Combahee River Raid in June 1862. She earned praise from the men she assisted on military expeditions, and finally, she secured a pension for her military service, after decades of inquiries and petitions. Following the Civil War, she became a suffragist, a respected reformer in her upstate adopted hometown of Auburn, New York.

This new image is captivating and surely the earliest portrait for which she ever sat; in this sitting Tubman appears to be in her mid-forties. During her lifetime, Tubman was rarely photographed, so unearthing this lost image is an historic find. This recovered portrait will have its public debut at a March 30th auction at Swann Galleries: 104 East 25th Street, New York, NY 10010—with previews of “Printed Manuscript and African Americana” from March 25 to March 29.

This discovery is just another example of Harriet Tubman’s star on the ascendancy. She is making up for lost time, expanding her circle of admirers even after her death on March 10, 1913. Relegated to a clandestine realm during her Underground Railroad years, Tubman was a widely heralded exemplar to her abolitionist brothers and sisters, including holy warrior John Brown, who addressed her as “General Tubman.” Enslaved African Americans came to regard her as the Moses of her people. But her emergence as an American patriot and hero has not had such a smooth journey.

Although former Union commanders commended her service and bravery, Congressman W. Jasper Talbert of Parkesville, South Carolina wanted to block Tubman’s pension, perhaps in response to her key role in the destruction of property and the liberation of slaves in coastal South Carolina during the Civil War. Nevertheless her campaign finally succeeded and in 1899 the government rewarded Tubman with a monthly pension. At her funeral, race leaders praised her exemplary role in the war against slavery, her crusades for education, and care for the needy. She opened a charity shelter for veterans, the elderly and disabled, a charity she ran until her later years. She finally donated her home to her church, and died there in 1913. With her death came nearly a half century of neglect of her key contributions to American history. Her exploits have been more celebrated on the children’s shelf rather than history textbooks.

But since the 1960s there has been a sure and steady revival of Tubman. Schoolchildren became smitten, after reading one of the more than 50 children and juvenile books in print by the turn of the 21st century. In the 1990s discussants on electronic lists and letters to the editor attempted to use Tubman in the debates over “gun rights v. gun control.” Tubman not only shouldered a rifle when she served with the Union army, but she always carried a pistol during her travels along the Underground Railroad. This matter of fact circumstance should not have had any bearing on contemporary political battles over guns, yet legend contributed to myth, and certain elements of the Black Power movement expropriated her as someone willing to use “any means necessary.” In a 2007 installation at London’s Victoria and Albert Museum (a bicentennial commemoration of the ending of the international slave trade) Tubman was featured as a “pistol packing” revolutionary. Tubman also sought to build through interracial cooperation and putting her Christian faith into action. Thus she had become a Harriet for all seasons.

At such a pinnacle of conflicted symbolism, her popularity elicited “blacklash.” Harriet Tubman became a “hot-button” for conservative critics. She became a symbolic “whipping girl” for political correctness. Lynne Cheney, the former chair of the National Endowment for the Humanities, was a fellow at a conservative think tank when she wrote in the Wall Street Journal in October 1994, condemning the forthcoming National History Standards: “As for individuals, Harriet Tubman, an African-American who helped rescue slaves by way of the underground railroad, is mentioned six times. Two white males who were contemporaries of Tubman, Ulysses S. Grant and Robert E. Lee, get one and zero mentions, respectively. Alexander Graham Bell, Thomas Edison, Albert Einstein, Jonas Salk and the Wright brothers make no appearance at all.” Cheney’s tote board approach and the tidal wave of condemnation of the history standards that followed drew the attention of the United States Senate. In January 1995 the Senate voted 99-1 to denounce the history standards.

Thus Tubman’s name was invoked to highlight “flaws” associated with new perspectives on core concepts within American history. Protracted debates in which opponents of the politics of inclusion hammered away at “revisionism” as a danger continue. But even as pundits bicker, Harriet Tubman’s legacy continues to blossom. She became an icon within popular culture.

Artistic representations of Harriet have been empowering. One of my favorites would be Jacob Lawrence’s stunning Harriet Tubman series (31 panels completed from 1938-40). There have been many more striking incorporations of Tubman’s image, and she has become a powerful “two-fer” on the cover of reference and textbooks, as her image conveys the inclusion of both race and gender.

But the measure of her growing presence might be the number of public sculptures that have been erected since the 1990s—giving her stature a boost through statues: a tribute to her partnership with Thomas Garrett in Wilmington, Delaware (1993), a group portrait erected in Battle Creek, Michigan in 1994, Tubman leading African Americans to freedom in Boston, Massachusetts in 1999, a statue of Tubman with a child in Little Rock, Arkansas in 2004, Tubman alone in 2006 in Bristol, Pennsylvania, and the monumental memorial to Tubman completed in Manhattan in 2008. She has even gone international with a bust of Tubman outside Salem Church in St. Catharine’s, Ontario, Canada (2010). A virtual explosion of markers track her contributions and fame, and it was a particular triumph when South Carolina in 2008 designated a bridge over the Combahee River to be named after Tubman, with a plaque commemorating her role in the Civil War raid.

Despite Cicely Tyson’s powerful portrayal of Tubman in a television miniseries in 1978, Tubman had a low profile in the broadcast and film realm until quite recently. The Hollywood Reporter announced in April 2015 that Viola Davis hoped to bring her hero to the screen for an HBO movie. And in February 2017, an independent biopic was announced, starring Tony award winning actor Cynthia Erivo (who won for her role in the Broadway musical, “The Color Purple”).

When Davis won an Emmy for her role in How to Get Away With Murder in September 2015, she paraphrased Tubman in her acceptance speech, an advocate on behalf of black actors: “ ‘In my mind, I see a line. And over that line, I see green fields and lovely flowers and beautiful white women with their arms stretched out to me, over that line. But I can’t seem to get there no how. I can’t seem to get over that line.’ That was Harriet Tubman in the 1800s. And let me tell you something: The only thing that separates women of color from anyone else is opportunity.”

In March 2017, Aisha Hinds will play Tubman as a series regular on WGN’s Underground. Accuracy is not well served by her appearing in publicity shots for the program toting a rifle— as her rifle was a Civil War rather than an antebellum accessory.

She was featured in the 2012 Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter—where along with First Lady Mary Lincoln she phantasmagorically saved the day by smuggling silver bullets to Gettysburg so federal troops were able to defeat the Confederate army of vampires. Tubman was featured in an episode of Drunk History, portrayed by Academy Award winner Octavia Spencer, with narration by Crissle West. Indeed she has had increasing cameos within pop culture, i.e. as a sculpture in butter for an Iowa state fair contest in the forgettable 2011 film, Butter, and the unfortunate “Harriet Tubman Sex Tape,” posted in August 2013 by Russell Simmons on his Def Digital Channel, before being removed following protest and Simmons issued multiple apologies. (But like so many “sex tapes,” the tarnish lingers on the Internet.) However, her image recently underwent a dramatic boost, as Tubman is at long last receiving homage and acclaim.

April 20, 2016 was the day Harriet Tubman was said to have “broken the Internet,” due to Googling of her name in the wake of Treasury Secretary Jacob Lew’s announcement that Tubman would be the new face on the front of a redesigned U.S. $20 bill. In Spring 2015, a Women on $20s grassroots crusade and later that same year a U.S. Treasury outreach campaign – the New Ten culminated in the realization of a dream for former U.S. Treasurer Rosie Rios (2009-2016), who advocated for women on the money during her time at Treasury. The grassroots Internet campaign conducted a poll with over 600,000 votes cast and Harriet Tubman declared the winner. Over a million and a quarter nominations were sent to the Treasury website soliciting advice for redesigning currency. The outcry over replacing Hamilton on the ten dollar note was perhaps an unanticipated hiccup, but Secretary Lew argued that the “family of redesigned bills” would maintain Hamilton while creating opportunities for more than just one woman, as Lucretia Mott, Susan B. Anthony, Alice Paul, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Sojourner Truth will appear on the back of the $10 bill, while Marian Anderson and Eleanor Roosevelt (joined by Martin Luther King) are proposed for the reverse of Lincoln’s $5 portrait.

But it will be Harriet Tubman—a solo and signature honor—who will adorn the front of the new $20 bill. All of these scheduled redesigns will be glacially slow for a public primed for viral response, but when I began my academic career over 40 years ago, the idea that such a sea change would happen within my lifetime, seemed a fantasy.

I did hope to survive to see the establishment of a national monument for Tubman. And the Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad Monument on the Eastern shore of Maryland will have its grand opening following Harriet Tubman Day—March 10th, the anniversary of her death. I also very much welcome the addition of the Harriet Tubman National Historical Park in Auburn, New York on the site of the charity home Tubman founded, adjacent to her own family homestead. A park was officially established in a signing ceremony on the 10th of January 2017.

And it’s especially gratifying to be able to give three cheers over the newly discovered portrait of Tubman. I remember my elation over the 2003 discovery of a runaway advertisement for her from a dumpster: as preservationists recovered an issue from an Eastern shore local paper from October 1849.

But the recovery of this portrait from a souvenir book that was purchased as unclaimed goods on the streets of New York has prompted nothing short of glee. So those of us addicted to searching for discarded valuables, for shining a light on lives that have too long been relegated to the shadows, can take heart. Harriet Tubman and her sisterhood are gathering hosannas long overdue.

In Viola Davis’s moving Oscars’ acceptance speech on Feb. 26, 2017, she paid tribute to both her family and to the great writer August Wilson, whose character she was privileged to play. She also suggested: “We are the only profession that celebrates what it means to live a life.” On Facebook, a colleague reported her daughter turned to her at this moment and asked: “What about historians?”

So let us remember that as Davis spoke about exhuming the bodies and exalting the stories, we historians must continue our quest to excavate lives long buried, to illuminate those in need of resurrection. And in this month of celebrating women’s history, in this season of Hidden Figures (based on the book by Margot Lee Shetterly) and the forthcoming television film of The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks (based on the book by Rebecca Skloot), we can celebrate women enjoying their long overdue cultural star turn. A very happy Harriet Tubman Day for 2017.

Catherine Clinton is the author of Harriet Tubman: The Road to Freedom, and most recently Stepdaughters of History: Southern Women and the American Civil War. www.catherineclinton.com

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com