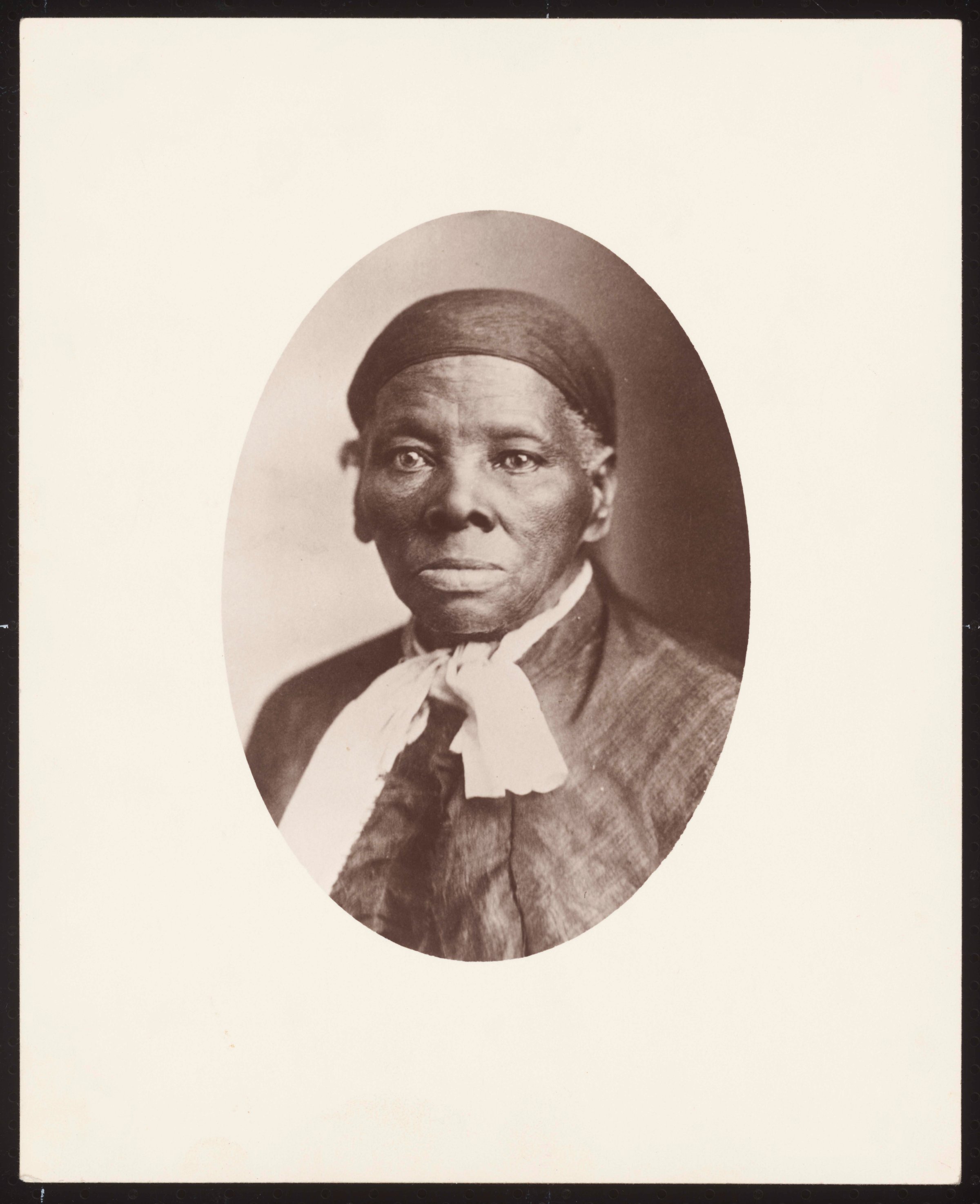

Ever since Congress designated March 10, 1990, “Harriet Tubman Day,” to mark the anniversary of her death in 1913, the date has become an opportunity to review the life and legacy of the “conductor” of the Underground Railroad, the secret network that helped fugitive slaves in the South get to free states in the North or in Canada.

But while many people have read about how she dressed up escapees in disguises in their history textbooks, they may not realize that she herself often dressed in lace and silk, even though she lived very modestly later in life, when she made sure that African Americans who had escaped from bondage had someone to take care of them in their old age, at her Auburn, N.Y., home.

One of the “most treasured” objects at the Smithsonian’s new National Museum of African American History and Culture is the white, silk and lace shawl that Queen Victoria gave Tubman in 1897 when the royal was giving out medals to heroes worldwide as part of her Diamond Jubilee.

“[Tubman] always wrapped herself in white later in life, on a daily basis, which was a strong, powerful color in West Africa,” says curator Nancy Bercaw.

But Tubman’s fine clothes — like the matching tea cups she used to serve her guests — had another meaning, too. For one thing, they sent a message to the rest of the world. She “put great stock in the politics of respectability,” Bercaw says, using propriety to protect herself and others from negative stereotypes about African-American women. But they also sent a message to those Tubman helped, demonstrating that all people deserved the respect signified by elegance. “It was very important to her to serve tea in a proper setting, demonstrating a common humanity and respect, of all individuals,” Bercaw says, “and I think some of her clothing was also speaking to that, an inherent human dignity.”

Bercaw adds that she hopes that this Harriet Tubman Day more people will remember the work Tubman did later in her life, in her wearing-white phase, and how she helped care for the elderly.

“I think people forget about the second half of her story—what happens to people when they become free?” she says. “Slavery was still continuing in people’s lives.”

Correction: The original version of this story misspelled Nancy Bercaw’s name.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com