It was around dawn on Oct. 17 when Kurdish forces began the long-awaited offensive to retake Mosul from the Islamic State. Two and a half years had passed since the group swept through northern Iraq, allowing a chance to dig in for the eventual counterattack. For months, photographers waited in the wings for word that the battle would begin. They knew it would be long, bloody, ruthless. But when?

Sebastian Meyer, an American photographer based in the Kurdish region of Iraq from 2009 to 2014, was working on a book about Kurdistan. He had no interest in the frontline anymore but knew the offensive was a crucial inclusion for his book. So a friend dropped him off at a medical clinic in Wardak, a tiny village about a mile from the front. There, he assumed the traditional role of the conflict photographer, capturing the mayhem close up.

Previously under ISIS control, the village had been wrestled back about six months earlier. Largely empty of civilians, he says it had become a base of sorts for forces preparing for the offensive. That night, he got about three hours of sleep, on a gurney in an ambulance. Meyer recalls it was still pitch black when the line of vehicles began to move toward the front around 3 a.m. In Wardak, the explosions began near dawn, these loud booms in the distance.

“A solid two hours went by, nothing. There was just thumps,” Meyer says. “Around 8 or 9, the first ambulance comes tearing down the dirt road.”

All the injuries that day were from improvised explosive devices, among the ugliest weapons in modern warfare. Men who left that morning returned limbless—eight of them, lifeless—within hours. “When you’re just covering the medical clinic, all you’re getting is the carnage side of it,” Meyer says. “You don’t see any successes, you just see the negative.”

One ambulance brought back a man who appeared to be dead on arrival. This was no young gun, but an older, seasoned fighter, respected within the Peshmerga ranks. “They brought him in thinking the doctors could do something, and the doctor takes one look at him and says ‘no,’” Meyer says. “Everyone’s in shock.” Nobody would call time of death.

A group hoisted the man onto an orange stretcher, his arms hanging off the sides. A large white bandage had been placed over his eyes. His green camouflage jacket was open, exposing an undershirt caked with dirt and stained with blood. Handmade tourniquets were loosely fastened on both legs.

They wheeled him around the corner to a spot under the shade. Meyer, who picked up Kurdish during his years in the region, understood much of the whispering. “[There was] a sense of reverence around him as people walked by,” he recalls. The man was among 24 casualties at the clinic that day, and one of four deaths that Meyer says was photographable. He tweeted a few pictures from the clinic, showing fatalities early into what was sure to be a long fight. Kurdish authorities were upset and booted him that afternoon. Later, the body was zipped into a bag and shipped back to Erbil. About three weeks would pass before Meyer would again think about the man on the gurney.

“The way that war reporting happens is we very rarely follow up with the families of people who die or are wounded or kidnapped. I think it’s important to show the ripple effects of something like this, of what it does,” he says. Speaking about the notion of relatability between subjects and viewers, he adds, “it’s the biggest challenge I think that we have.”

He knew the man’s name (Kamaran Omar) and his rank (captain). Finding the family wasn’t difficult in a place as small as Kurdistan. Through a friend in the local media, and three phone calls later, he was introduced to Kamaran’s nephew, Hazhar. By that time, Kamaran was buried.

Hazhar allowed Meyer to tag along when the family visited the gravesite a month after Kamaran’s death. They met outside a mall in Erbil and drove about a half hour away to the village of Sewaka. On the way, Hazhar says in a phone call with TIME, he showed Meyer photos of him washing Kamaran’s body at the mosque. He told Meyer that Kamaran was one of seven brothers, and the fourth to die on the battlefield over the past three decades.

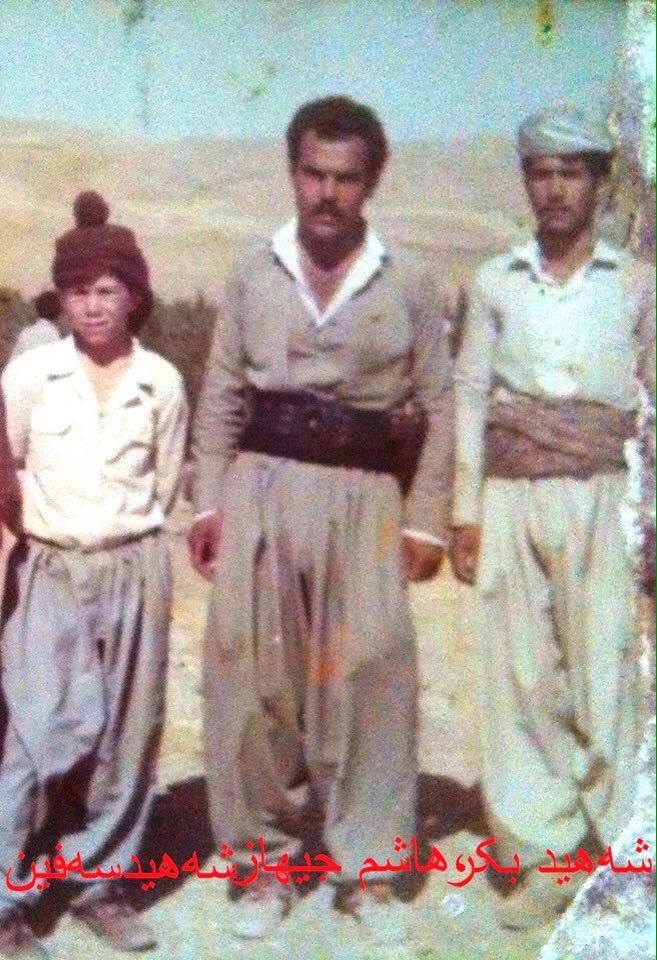

The first was Safen. In November 1987, nine months after he was smuggled into the Peshmerga as a 17-year-old, he was killed fighting on the front line against Kurdish fighters allied with Saddam Hussein’s forces.

The second, Hashim, was the eldest of the brothers. He was conscripted, joining the Iraqi army’s communications division. After more than a year, Hazhar says, he deserted to join the Peshmerga. In the mid-1990s, that militia was divided against itself, with forces split between rival political parties, the KDP, or the Kurdistan Democratic Party, and the PUK, or Patriotic Union of Kurdistan. As the civil war raged, the KDP allowed Hussein’s army to rout the PUK from Erbil. Hashim was captured by the KDP and, Hazhar says, thought to have been handed off to Hussein’s forces and disappeared. His body was never found, his tale became the stuff of lore.

Bekir, the third son to die in battle, spent 25 years of his life with the Peshmerga. The third-youngest of the four, he was the first to die against ISIS. His group was holding a front near Makhmour, on the plains south of Mosul, in 2014 when the militants attacked, leaving 14 Peshmerga dead. Bekir was shot five times, including in the left side of his chest, near the heart. He died five days later.

Kamaran, born in 1972, was a quiet boy, Hazhar says. When he was young, during his studies, he worked at the family’s bakery part-time. When he was a teenager in the city and Hashim was with the Peshmerga in the mountains, he would bring things like food and medicines and letters containing sensitive information back and forth. In 1991, he joined the Peshmerga as a fighter and rose up through the ranks. He was a veteran by the time the Mosul offensive began.

In a conversation after Bekir’s death, Hazhar recalls Kamaran saying, “I miss all three brothers, I want to see them, I want to be with them.” Hazhar urged him not to joke about death. “You have to look after your kids. If you go to them, who will look after your kids?” He had five children: three sons and two daughters.

This family’s sacrifice is more extreme than most, Meyer says. Certainly there are families that have lost like this and more, but four brothers who died in the handful of major conflicts of modern-day Kurdistan is rare.

The day at the cemetery was dry, and the sun had already started to fall. Relatives gathered around a row of three plots, the newest covered by a blue tarp and held down with stones. Underneath was a Kurdish flag, also held down with stones.

Mourners began to recite prayers. After a while, the men pulled back, leaving Kamaran’s two daughters, his wife, mother and a few others. Islamic prayers could be heard from a cell phone as the daughters comforted one another, then comforted their mother.

Later, on the way back to Erbil, Hazhar told Meyer more about the family. Of the three brothers who are left: one works in the oil business, another lives in Holland and the third, previously in the U.K., returned to take care of their mother.

Kamaran’s funeral was broadcast on several regional television networks, and the family’s sacrifice over three decades duly noted. “OK,” Hazhar says people would tell them, “your family has given enough.”

Sebastian Meyer, based in Brooklyn, is a documentary photographer who was based in Iraqi Kurdistan from 2009 to 2014. His book, Under Every Yard of Sky, will be published in late 2017 by Red Hook Editions.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com