This post is in partnership with the Harry Ransom Center at The University of Texas at Austin. A version of the article below was originally published on the Ransom Center’s Cultural Compass blog.

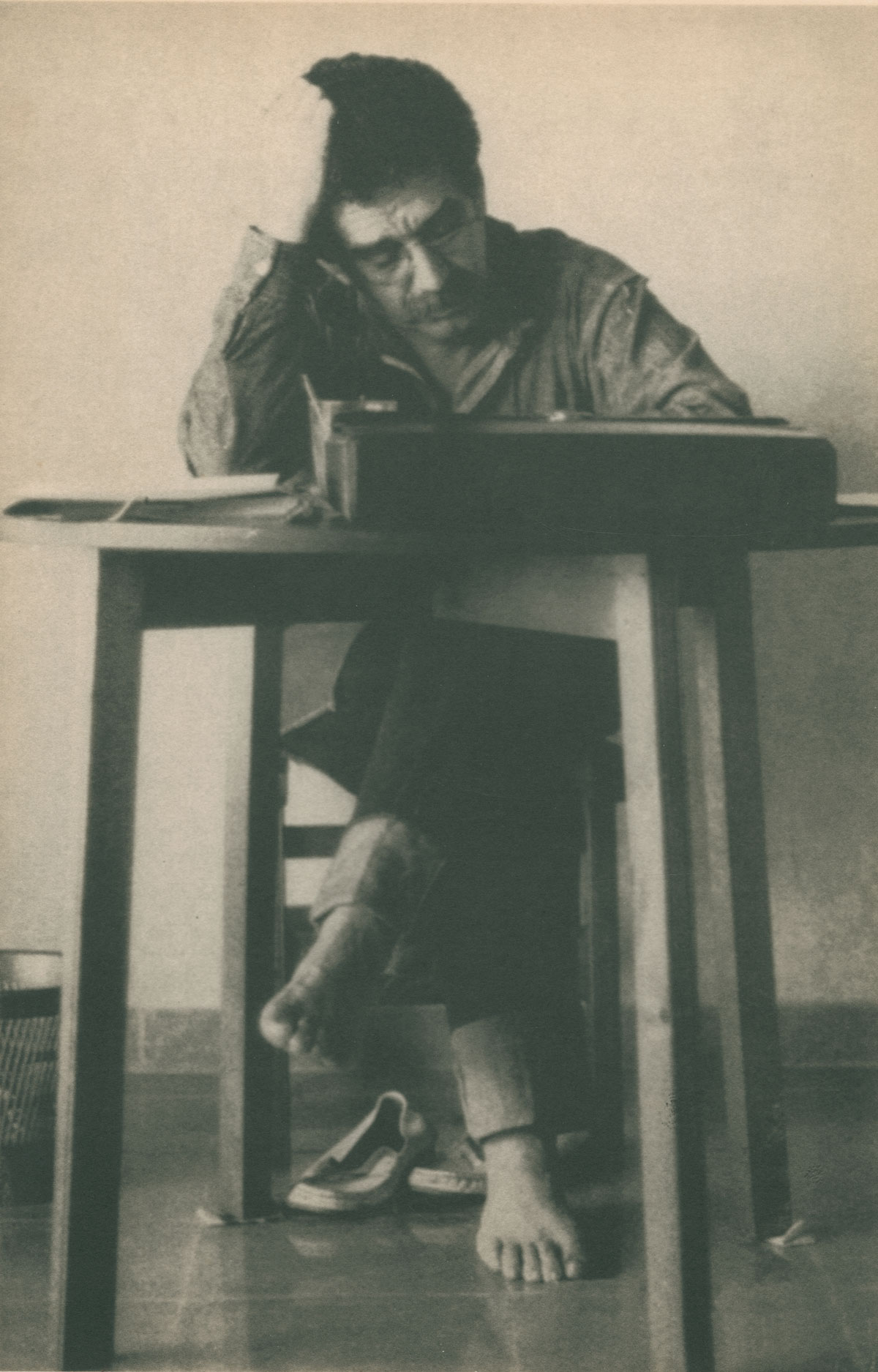

In August 2016, I joined the Ransom Center as a graduate student assistant from The University of Texas at Austin’s School of Information to digitize the Gabriel García Márquez papers. The project’s title, “Sharing ‘Gabo’ with the World,” reflects the intentions of the Council on Library and Information Resources’ grant: to make accessible digitized content from García Márquez’s voluminous collection of manuscripts, notebooks, scrapbooks, and photographs. My first weeks entailed digitizing pages of García Márquez’s manuscripts.

Several months later my supervisor, Jullianne Ballou, asked me to select about 100 photographs for digitization from among the thousands that arrived with the collection. It wasn’t until I was facing a collection of 24 boxes containing dozens of folders with titles like “Gabo con Presidentes,” “Nobel Prize,” and “Gabo con Fidel” that the difficulty of selecting so few photos to represent such a remarkable life set in.

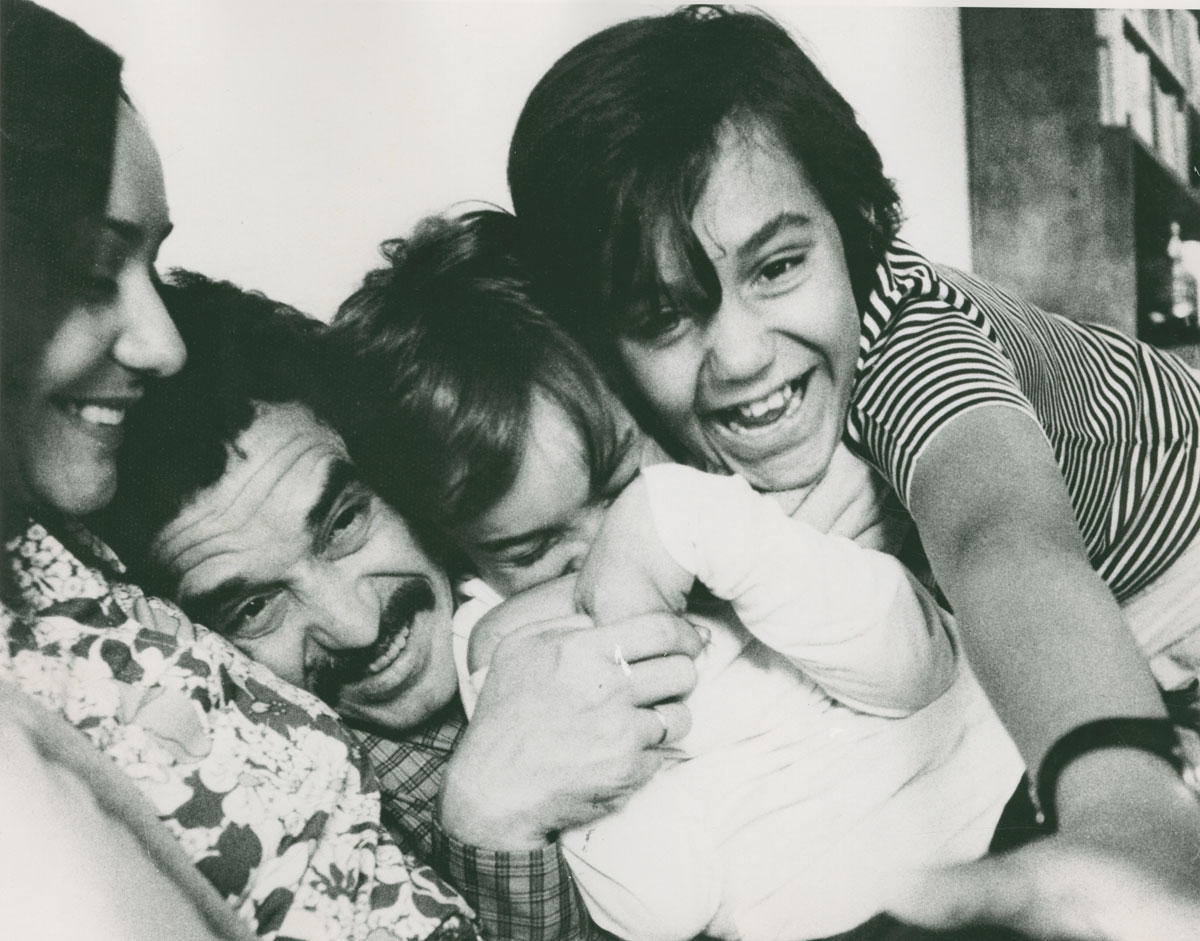

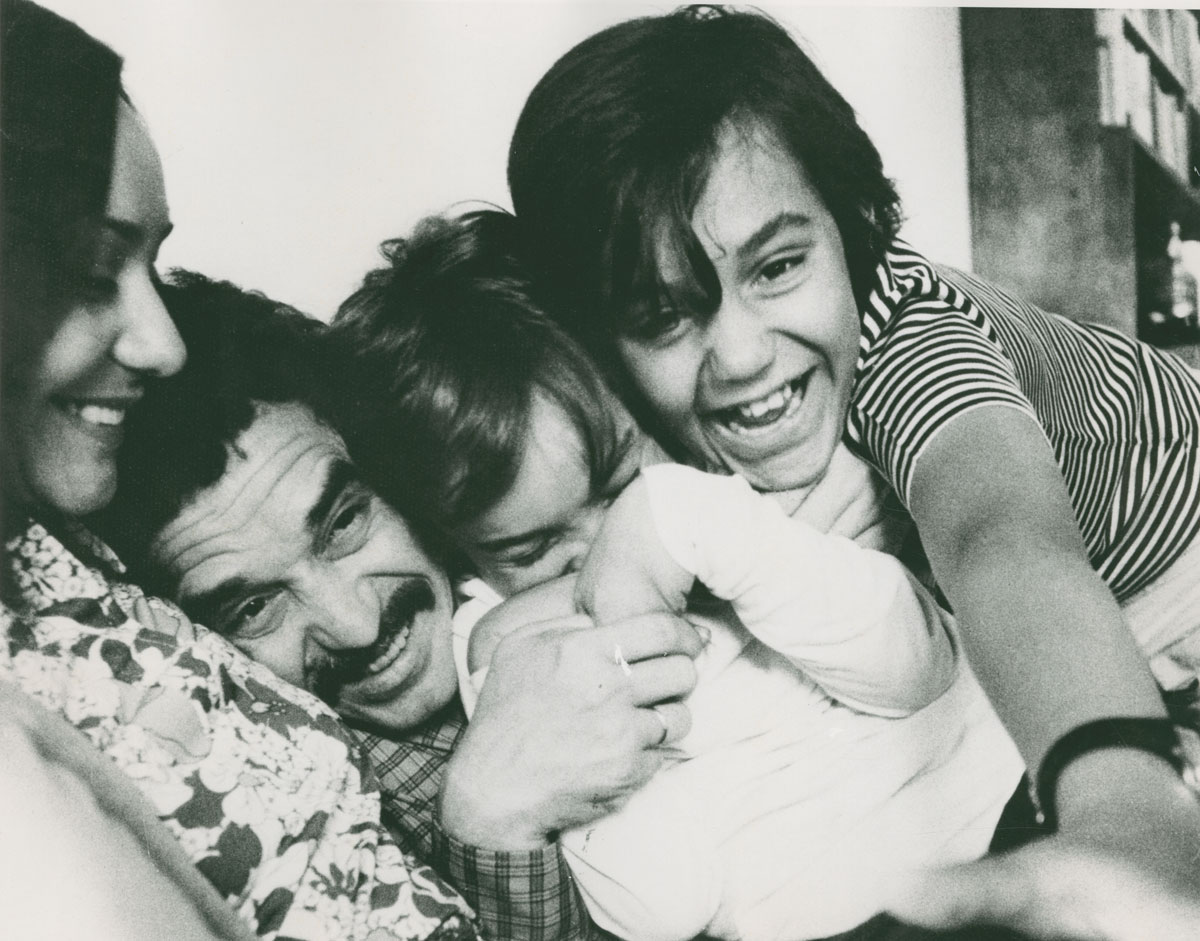

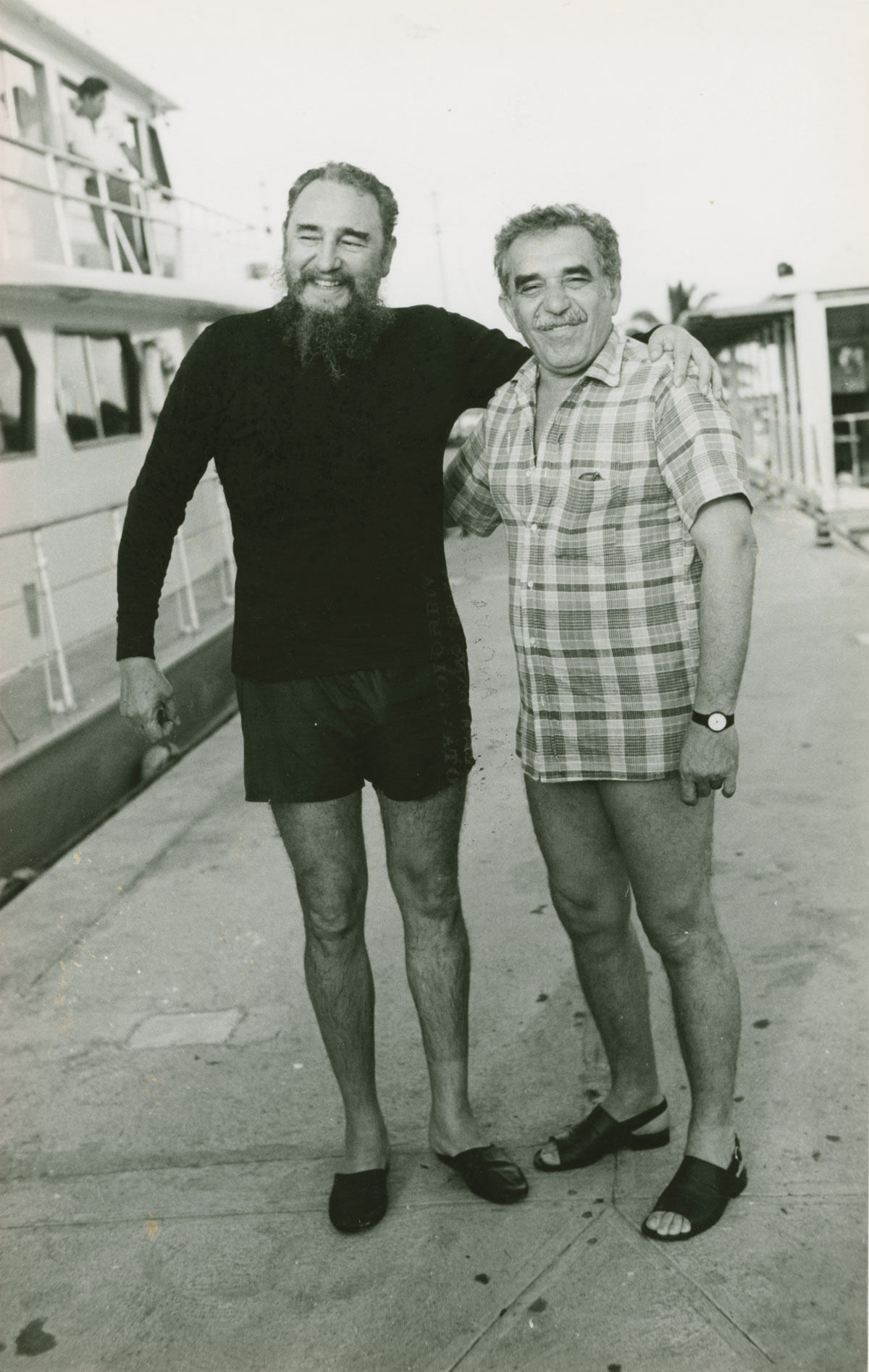

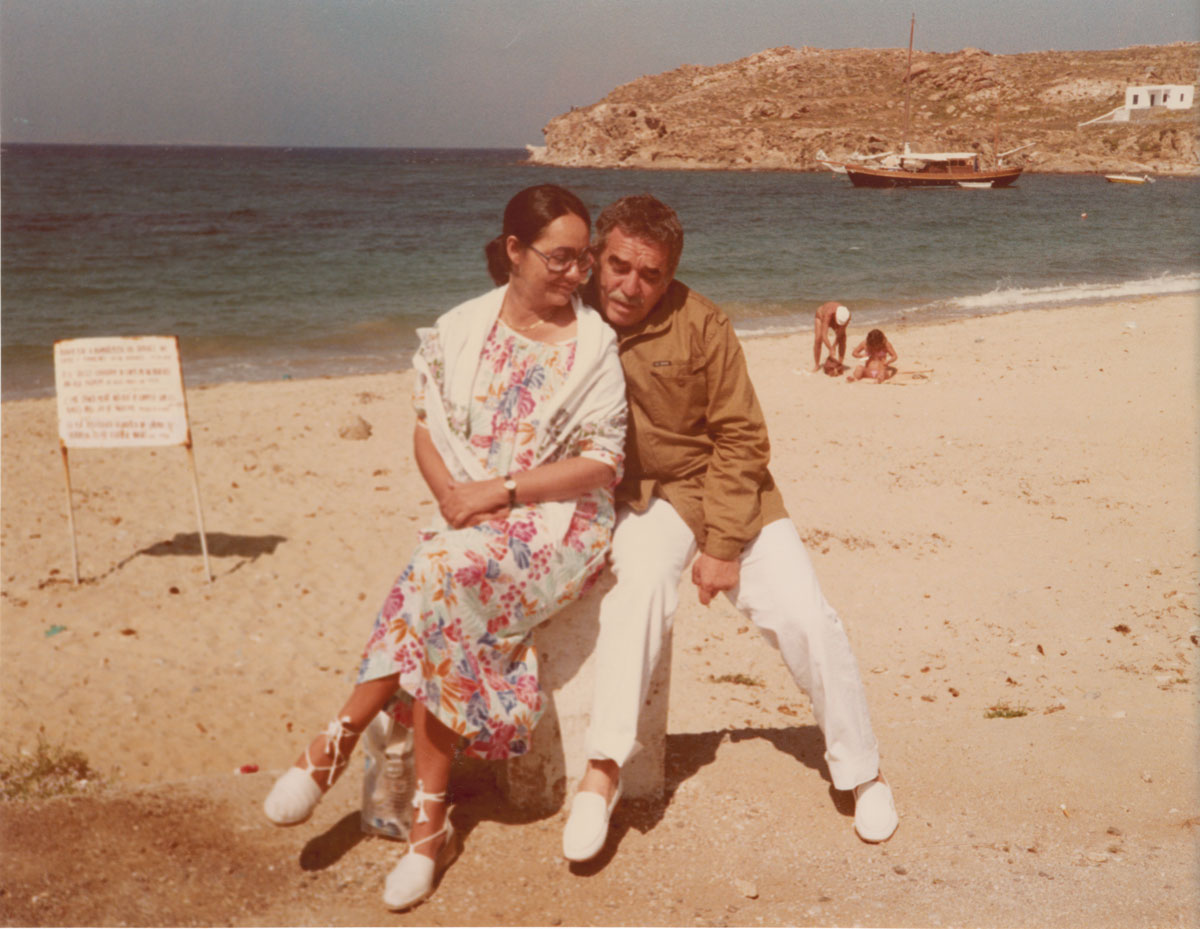

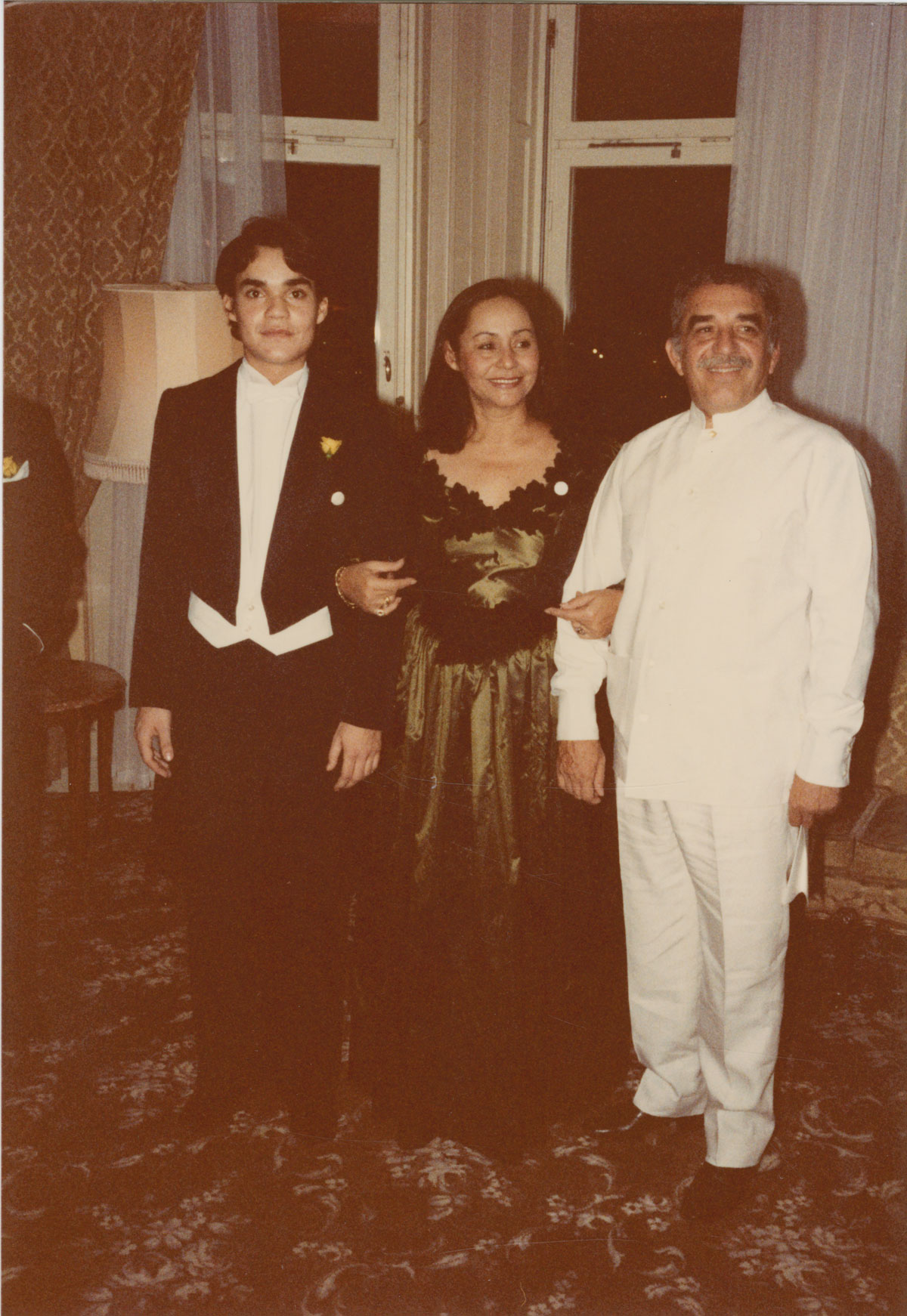

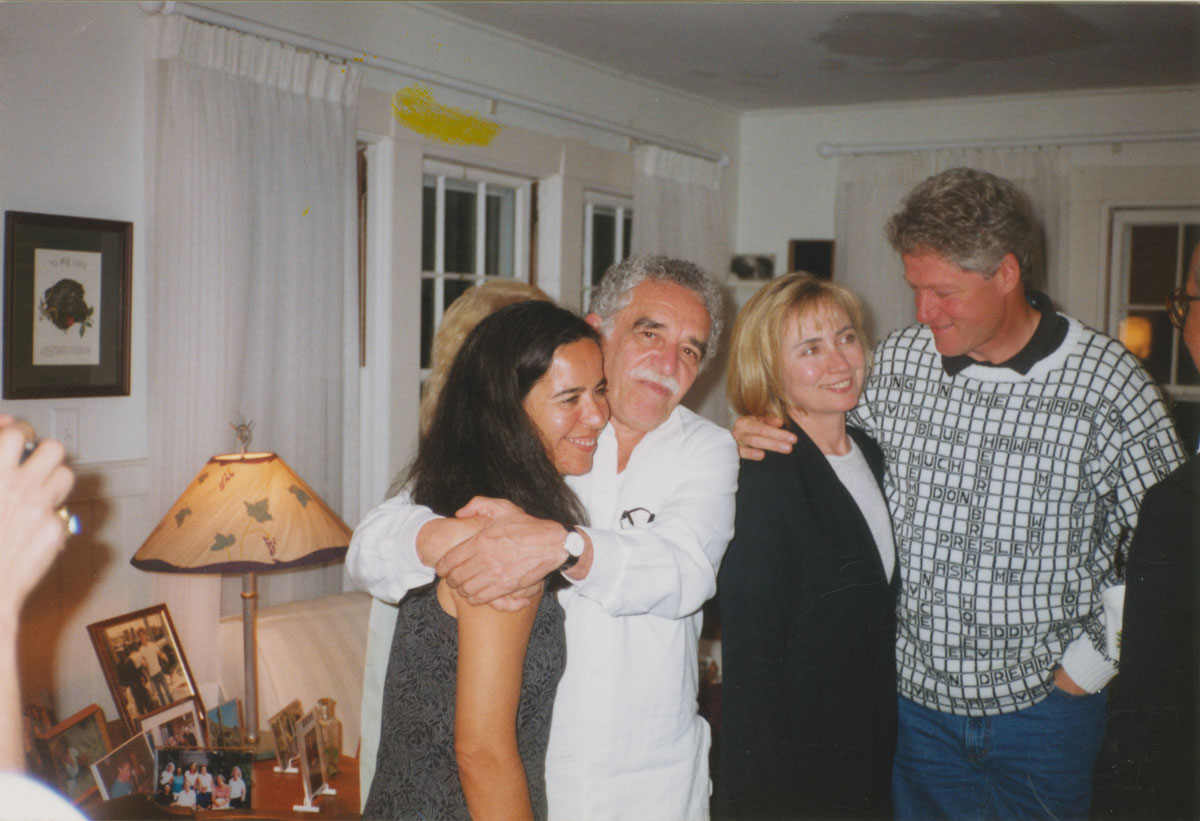

Should I prioritize García Márquez’s personal and professional friendships, so numerous and long-standing that a full seven albums carried the title “Amigos”? How can I do justice to his 56-year marriage to his beloved wife Mercedes, described by biographer Gerald Martin as “indispensable to a man who considered himself absolutely self reliant,” and their two children? Certainly the decades-long friendship with Fidel Castro could supply more than 100 worthy photos: images of the two men depict the reliably stern Castro letting his guard down just about any time Gabo is in the photo. Gabo’s association with Bill Clinton in the mid-1990s was also a rich source of noteworthy photos. Then there’s the Nobel Prize, of course, and the numerous photos of jubilant Colombian friends and family who accompanied him on the trip to Stockholm, but other awards like France’s Legion d’Honneur and the Orden Mexicana del Águila Azteca also demanded consideration. How many of the photos should represent his novels, and how many his journalism or his screenwriting?

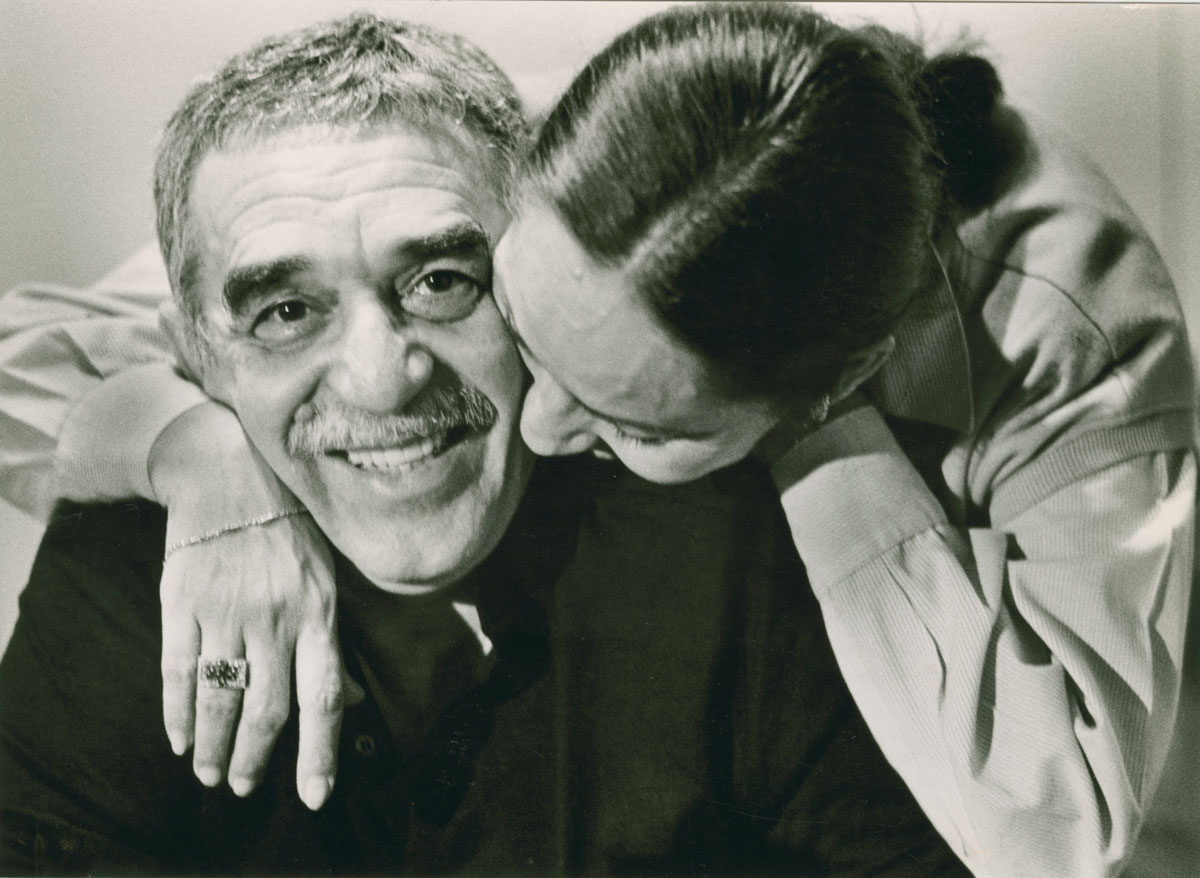

All of which is to say that it was even more difficult to be discriminating with the photos I selected. So many photos seemed significant, and each folder seemed to present a new side or aspect of Gabo, the omission of which would feel like an injustice. I felt a real responsibility to assemble an accurate visual representation of García Márquez’s remarkable life each time I flagged a photograph. This sense of obligation to the collection’s creator was only heightened by virtue of working with the materials of the illustrious “Gabo,” one of the most acclaimed and significant writers of the twentieth century.

Ultimately, revisiting a fundamental archival principle clarified my role: not to compile a comprehensive summary of Gabo’s impossibly rich 87 years, but simply to provide a glimpse into a more complete collection. This concise yet (if I did my job right) accurate overview of the contents would compel the archive’s audience to explore further—either by coming to the archive or by working remotely with a local researcher at the Ransom Center. Generally speaking, as archivists our role is chiefly to make a collection accessible. This means providing an overview of the contents—and letting the researchers and scholars take it from there. In my short archival career, I’ve found this to be an ever present tension: the push and pull between wanting to share the interesting and personally compelling finds from within a collection and remaining faithful to your role as an archivist.

With Gerald Martin’s meticulously researched biography Gabriel García Márquez: A Life to help fill in gaps and provide names, places, dates, and context to the collection, I gradually grew more confident that I could both remain faithful to my archival mandate and provide an accurate, if somewhat limited, portrait of Gabriel García Márquez’s irresistible personality. Before I had seen several distinct aspects of a life that were difficult to reconcile, but as I worked I began to see that literature was the thread that tied these aspects together.

The famous friendships with Clinton and Castro, for example, were founded on a mutual love of literature. Gerald Martin writes of the first meeting between Clinton, García Márquez, and Mexican writer Carlos Fuentes, in which the two writers were astonished by the new president’s parrying their attempts to raise the Cuba embargo by steering the conversation to William Faulkner and citing long passages from memory. Martin also recounts that García Márquez insisted his conversations with Fidel were about literature. Though his personal politics were likely more closely aligned with Castro than with Clinton, finding common ground in appreciation of literature underpinned the improbable but genuine dual friendships with the Cuban revolutionary and the American centrist.

Mutual admiration for the power of words also led to García Márquez’s meeting and interview with Subcomandante Marcos and the Zapatista movement (first question: “Do you still have time to read in the middle of all this mess?”), and his socializing with men of unimaginable wealth like Mexican billionaire Carlos Slim and Colombian businessman Julio Mario Santo Domingo. Gabo hoped that his most powerful and influential friends might bring attention and funding to groups and causes he’d become familiar with in his work as a journalist and in which he believed deeply.

There are the obvious ties to literature in the pictures of Gabo with colleagues from Prensa Latina, the Cuban news agency he helped launch; they are less evident in numerous photos with longtime friend Shakira. But the Colombian city of Barranquilla played an important role in both of their lives, as the city that launched both her music career and the mid-twentieth century circle of writers, journalists, and philosophers in which Gabo played a pivotal role.

So while Gabo was a man of many sides, he was above all a writer, and literature was the guiding force in his life. That seems an obvious conclusion to reach, perhaps, but while his celebrated writing career enabled his impossibly rich life, I also got the sense that he would have been essentially the same person without the presidentes, the personal audiences with the Castro brothers, the stately and elegant awards ceremonies, and the wealthy and influential friends.

The digitized archive of Gabriel García Márquez, including these photographs, will be available for research online in December 2017.

See more from this collection here, at the Harry Ransom Center Cultural Compass blog

Related content

Award supports digitization of more than 24,000 images from the Gabriel García Márquez archive

Preserving Gabriel García Márquez’s life and legacy

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- How Elon Musk Became a Kingmaker

- The Power—And Limits—of Peer Support

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com