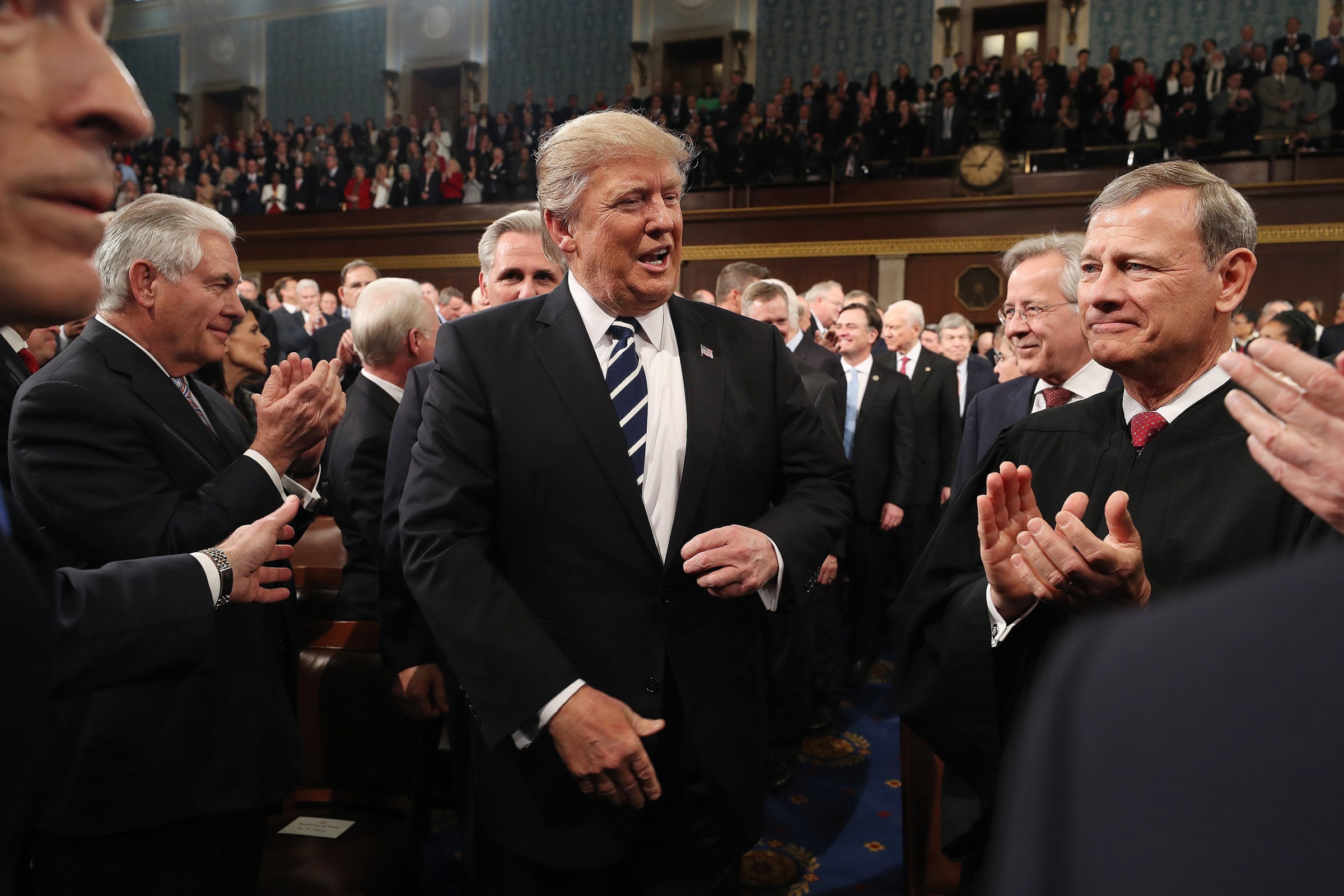

On his 40th day as President, Donald Trump stepped up to the biggest megaphone his office provides–the prime-time joint address to Congress, a speech usually chock-full of real-life stories, uplifting rhetoric and promises of change. Trump followed the pattern too, pleading for new infrastructure projects, vastly more military spending and broad tax and trade overhauls. And he vowed to roll back the biggest leftover from the Obama era: “I am also calling on this Congress,” Trump said, “to repeal and replace Obamacare with reforms that expand choice, increase access, lower costs and, at the same time, provide better health care.”

Republicans in the House chamber cheered so earnestly that it all sounded easy. In theory, it should be easy: the GOP controls the White House and both chambers of Congress. In fact, problems await Trump’s agenda at every turn. The Republican tax-reform plan has sparked a backlash from key GOP Senators, big-box retailers and powerful conservative advocacy groups with millions in ads at the ready. The plan to repeal and replace Obamacare faces a two-front revolt in the House, where some Republicans think the working replacement plan is too severe, while others believe it would permanently enshrine a new big-government entitlement. Even the plan to pour billions into the Pentagon is unlikely to happen while Republicans protect cherished programs in law enforcement, diplomacy and education.

As a business mogul, Trump has typically thrived amid chaos. But now that he’s President, the stakes are higher and the players far more difficult to manage. The Republican math for getting things passed remains unforgiving, prompting no less a figure than former House Speaker John Boehner to predict a quick end to GOP “happy talk” about repealing and replacing Obamacare quickly.

One ally of House Speaker Paul Ryan, Representative Mark Walker of North Carolina, who chairs the roughly 170-member Republican Study Committee, has already come out against the draft health care plan because it would create individual tax credits to help pay for health insurance, which conservatives view as yet another costly entitlement program. Representative Mark Meadows, also of North Carolina, who chairs the more conservative, roughly 40-member Freedom Caucus, has joined the rebellion. “We can’t vote for the current plan as it is,” Meadows says. “That dog doesn’t hunt.”

On Ryan’s left are Republican moderates, many from swing districts, who want to have a safety net in place before Obamacare is repealed. “Now we’re in charge and we’re firing live rounds,” Representative Charlie Dent, a Pennsylvania centrist, tells TIME. “It’s incumbent upon us not to only deal with repeal but with replacement.” In the House, 23 Republicans won election in November in districts that Hillary Clinton carried. And Republicans can only afford 23 defections if the Democrats remain united.

Ryan’s plan to break the standoff is to create a crisis. Congress has been conditioned in recent years to act only when pushed to the edge–whether a real crisis, or one of its own making. At some point this spring, he hopes to force Republicans to make a choice between voting for his blueprint or explaining the failure to pass anything to their constituents back home. “It’s probably going to be at the brink a few times before we get there,” a top aide to House Republicans tells TIME. “Everything big is.”

In that environment, what role does Trump play? “There’s only one person out of 320 million Americans who can sign a bill into law, and that’s the President,” said Senator John Thune, a South Dakota lawmaker and the third-ranking Republican on his side of Capitol Hill. Long averse to the fine print of policy, Trump has so far decided to avoid courting votes one by one, although his team has been ramping up the invites to the White House bowling alley and scheduling frequent visits to Capitol Hill by Vice President Mike Pence, a former House member. In the President’s regular phone calls with the Speaker, the most common question is not about the substance, but “When can you do it?” say Capitol Hill aides.

The answer is as soon as Ryan can find the votes, a refrain that is likely to be repeated again and again. Complicating Republican efforts is the money crunch: repealing Obamacare, depending on the details, could add to the deficit, along with Trump’s other legislative priorities, like building a wall with Mexico and a $1 trillion new infrastructure program. To date, Trump has said he will not seek cuts in either Social Security or Medicare to fund his agenda, although Ryan has said the President might come to alter that view. “This is not rocket science,” says Representative Mike Simpson, an Idaho Republican. “You’ve got to touch entitlements.”

That’s where the GOP’s other big priority, corporate tax reform, could come into play. House Republicans are pushing a plan to lower corporate tax rates and completely reimagine what kind of earnings and profits the revised taxes target. Their proposal would exempt exports from taxes and levy new taxes on imports, raising more than $1 trillion over the next decade. It’s a complex plan that would place new burdens on importers and ease restrictions on exporters. And that is precisely where its chances of passage get dicey.

Trump has seemed open to the proposal and mentioned the disparity between imports and exports to Congress during his joint address. But as with health care, he has not committed to specifics. Retailers, who depend on imports, have started running millions of dollars in ads opposing the “border adjustment tax,” as it’s called, arguing the plan would increase prices. (Many economists argue the price spikes would be short-lived, as currency markets adjust to the new regime.) Rank-and-file lawmakers see only trouble back home for businesses that bankroll their campaigns. Key Senators like John Cornyn, Tom Cotton and Mike Lee are urging the plan’s supporters to look for change in the couch cushions instead. The proposed border tax, says Matt Schlapp, the chairman of the American Conservative Union, “is wounded for sure.”

Straddling all this infighting is Senate leader Mitch McConnell of Kentucky, who is none too eager to stick out his neck for a health or tax plan that his members may never vote on. McConnell has been telling fellow Republicans that Ryan’s agenda might be dead on arrival in the upper chamber if he doesn’t consider how the slow-and-steady Senate will react. A McConnell adviser noted with a smirk that, when Trump speaks of Congress, he mentions Ryan by name but rarely McConnell. If the Trump agenda stagnates, Ryan is likely to shoulder more of the blame.

It’s just another sign that the Republicans are still getting accustomed to being the party in power.

–With reporting by SAM FRIZELL/WASHINGTON

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Philip Elliott at philip.elliott@time.com