I have never bought a camera.

I don’t enjoy photography. Yet I have saved 6,982 photos and 144 videos since my cell phones started coming with built-in lenses. I have recorded my family history dutifully–exactly as Kodak first began instructing moms to do in the 1890s–capturing birthdays, vacations, grandparent visits, first bicycle rides. But the bar for a Kodak moment has clearly been lowered. I have more than 7,000 of these things. I am creating a massive museum to myself that no one will ever enter. Not even me.

In 2011, Stanford students Evan Spiegel and Bobby Murphy figured out that photos had been massively revalued and no one had noticed. In an 1859 essay in the Atlantic, Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr. called the camera a “mirror with a memory;” Spiegel and Murphy realized that having a zillion memories can be a burden. So they created Snapchat, an app in which images that are sent disappear after one viewing. Snapchat contended that because photography is now free and frictionless, it is a medium for communication, not commemoration. As a result, Snapchat’s parent firm, Snap, isn’t really a social-media company. Instead of likes or comments or forwards, its currency is the “streak,” a calculation of how many days you and another person have privately communicated with each other. It trades in intimacy, not popularity. As its name so neatly explains, Snapchat is really a utility company for visual texting.

At a lunch awhile back, Snap CEO Spiegel put his smartphone on the table and told me that it had replaced the Internet, and now he wanted to figure out what was going to replace the smartphone. Much of Silicon Valley is trying to discover that. Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg thinks the answer is going to be virtual reality; Amazon’s Jeff Bezos is betting on voice recognition. Spiegel believes in the camera.

That belief is about to be put to the test, as Snap heads to the New York Stock Exchange via one of the most anticipated tech IPOs in years. The parent company of disappearing-message app Snapchat priced its shares at $17 in its IPO on March 1, raising $3.4 billion and valuing Snap at $24 billion. Which is pretty remarkable for a company that lost $515 million last year on revenue of $405 million. Snap’s valuation could have been even higher, but Spiegel created a rule that is so unfriendly to investors that no other U.S. public company has ever dared to try it: none of the firm’s public shares will come with voting rights. Spiegel’s and Murphy’s shares, however, will continue to have voting power for nine months after they die; investors cannot even pry the company from their cold, dead hands. At Stanford, Spiegel was a product-design major, and he keeps a painting in his office of Steve Jobs, a man he seems to admire for everything except the fact that he wasn’t controlling enough.

Snapchat makes visual communication so frictionless that, according to Nielsen, it is used by roughly half of 18-to-34-year-olds, which is about seven times better than any TV network. Those who use it daily open the app 18 times a day for a total of nearly 30 minutes. Last fall, Snapchat passed Instagram and Facebook as the most important social network in the semiannual Taking Stock With Teens poll by the investment bank Piper Jaffray. Tweens used to count the days until they turned 13 so they could open a Facebook account; now they often don’t bother. And just as Facebook matured years ago, Snapchat is starting to be used by adults. The company says the app is now used by 158 million people daily, though that growth has slowed a bit lately.

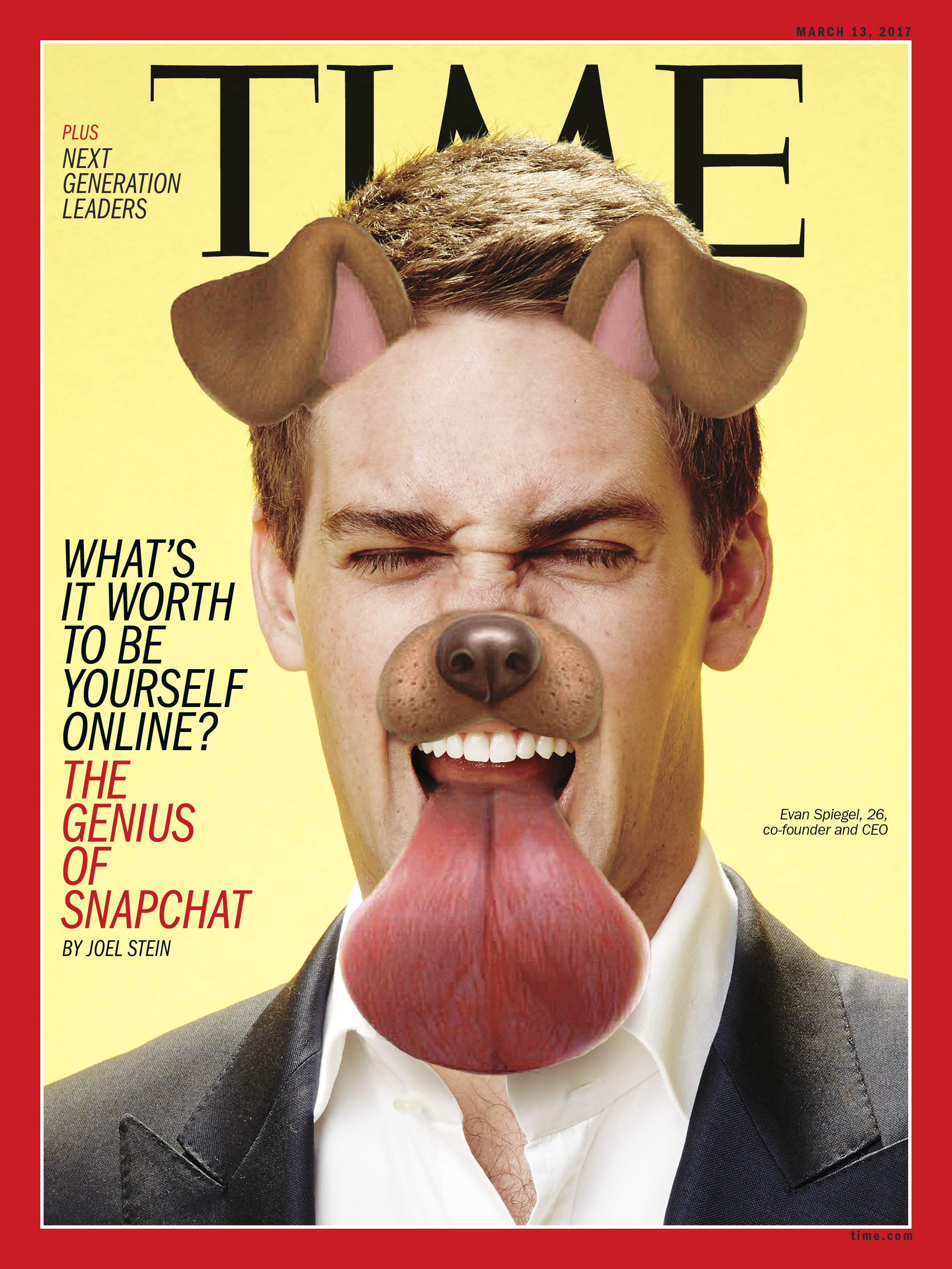

Snapchat’s ethos is largely about the seemingly contrary values of control and fun: the company prospectus is one of the few in Wall Street history to use the word poop, employing it to explain just how often people use their smartphones. Snapchat gives users such tight control of their disappearing messages so that they feel safe taking an imperfect photo or video, and then layering information on top of it in the form of text, devil horns you can draw with your finger, a sticker that says “U Jelly?” or a filter that turns your face into a corncob that spits popcorn from your mouth when you talk. Snapchat is aware that most of our conversations are stupid.

But we want to keep our dumb conversations private. When Snapchat first launched, adults assumed it was merely a safe way for teens to send nude pictures, because adults are pervs. But what Spiegel understood is that teens wanted a safe way to express themselves.

Many teens are so worried about projecting perfection on Instagram that they create Finstagram (fake Instagram) profiles that only their friends know about. “Teens are very, very interested in safety, including something they call ’emotional safety,'” says San Diego State psychology professor Jean Twenge, author of the forthcoming iGen: The 10 Trends Shaping Today’s Young People–and the Nation. “They know on Snapchat, ‘If I make a funny face or use one of the filters and make myself look like a dog, it’s going to disappear. It won’t be something permanent my enemies at school can troll me about.'”

The technology successes of the Internet age have been about making information free and easy. But Snapchat is a tech reactionary, offering an escape from the gameified popularity contest measured in friends, followers, likes and comments. Snapchat is built by and for a generation that wants to use technology to improve its antisocial social life.

Evan Spiegel is not exactly the prototype hero who saves humanity. Take a look at him: he could be cast in a teen movie as the preppy kid who beats up nerds and then drives away in his Ferrari with a license plate reading H8 nerds. He grew up in Los Angeles with an allowance of $250 a week. As the social chair at Kappa Sigma, he sent out misogynistic emails, including ones about “sororisluts” and joking about shooting “lazers at fat girls.” He’s engaged to former Victoria’s Secret model Miranda Kerr. He flies helicopters and actually does own a Ferrari. The guy even posed in L’Uomo Vogue wearing a Brioni fur coat while hugging a puppy. Bond villains have better optics.

Heroes are supposed to be ordinary outsiders who encounter tribulations, learn humility and make great sacrifices. Spiegel has done none of that. And that could be exactly why he might help rescue the online world from the trolls, fake news, hacking and narcissism that are eroding our culture.

Hemant Taneja, a managing director at the venture-capital firm General Catalyst, invested in Snapchat after hearing Spiegel’s pitch that virtual life should conform to real life, where you express who you are in different moments and around different people. “Products reflect the founders behind them. Mark [Zuckerberg] was this guy who is not very social in college–the guy outside looking in. ‘I’m missing out and I need to figure out what’s going on and I need to see everything.’ The choice of making Facebook completely open has created a lot of chaos,” Taneja says. “Snapchat reflects Evan’s ethos. It’s all about privacy and using technology to live the way you’ve always been.” Political philosophers worry about private information being seen by the government, insurance companies and employers. Normal people worry about being made fun of by their friends. Or lectured by their parents. But because Snapchat communication is private, kids can give their parents their Snap codes as freely as they do their phone numbers. As Spiegel said at a conference last year, “We’ve made it very hard for parents to embarrass their children.”

In 2013, Snapchat had rattled Facebook enough that it offered then 23-year-old Spiegel $3 billion in cash for the company. He turned it down, garnering mockery for his hubris, already famous in tech circles for moves like shunning Silicon Valley to build his company by the ocean in the Venice area of Los Angeles. When Sony was hacked by North Korea, one of the emails from CEO Michael Lynton, an early Snapchat investor who announced in January that he will leave his job to become chairman of Snap, implied that the offer was higher than $3 billion. “If you knew the real number,” he wrote, “you would book us all a suite at Bellvue [sic].” But a rich, cocky 23-year-old is uniquely empowered to turn down $3 billion. He was living in his dad’s huge house, getting meetings with anyone he wanted. Snapchat was a once-in-even-his-lifetime chance to build something unique.

Spiegel declined to comment for this story. But in an interview in 2013, his views on Snapchat’s place in the world were already clear. “Having this online world allowed my generation to support the illusion of being special,” he told me. “You could pick out your vacation in Maui and be that person, that collection of great, beautiful moments. But now there’s no gap between offline and online. So we’re trying to create a place that is cognizant of that, where you can be in sweatpants, sitting eating cereal on a Friday night and that’s O.K. It’s O.K. to be me even though I’m not on a fancy vacation and great-looking all the time. People are shifting from the self-promotional view of the world to one that is more self-aware.”

Snapchat accomplishes privacy not just through disappearing messages, which other companies had provided before, but by fully divorcing from the Internet. You can’t link out of the app to a news article or a website. You can’t even forward someone’s message or “story”–the 24-hour-lasting public-facing posts that anyone can see if they find your screen name, which is not an easy task. On Twitter or Facebook, if you don’t want to know about what Donald Trump said five minutes ago, too bad, someone is going to tell you. On Snapchat, if you don’t choose to follow DJ Khaled, the app’s biggest star, you never have to find out how #blessed he is. So celebrities use it not so much to increase their fame but to share less-filtered versions of their lives to their truest fans. Snapchat is the most troll-resistant online platform.

“The fact that it disappears in 10 seconds, I don’t trust that, but I value that it’s not creating a catalog of my tweets to my cousin who is in high school,” says New Jersey Senator Cory Booker, who Snapped his trip to and from Trump’s address to Congress on Feb. 28. “It creates a freedom to be silly in a way I just wouldn’t do on Facebook or Instagram. I could show Hillary Clinton being fun and lighthearted waiting to go onstage. Then I could show a more serious speech. It lends to a multilayered, authentic view of what life is all about. As much as you want to criticize Donald Trump, as far as social media, he is being authentic on those platforms. He’s creating connections.” On March 1, Arizona Senator John McCain, 80, got his own Snapchat account.

Because it’s not a forwarding mechanism that can make messages go viral, Snapchat is not the route to fame and fortune that YouTube, Instagram or even Twitter can be. “Culturally, Snapchat has become a very important platform in a lot of cool ways,” says Alec Shankman, the 37-year-old head of alternative programming at Abrams Artists Agency, who represents social-media influencers. “The only downside is that from a creator standpoint, it’s harder to be found and monetize.”

Snapchat indeed has a monetization problem: How do you sell ads if you’re essentially a phone company that has chosen to provide free calls forever? Yes, advertisers can slide 10-second commercials into people’s stories, create filters (Taco Bell let users turn their faces into taco shells on Cinco de Mayo) and suggest geo-locators to put on the bottom of photos (college students were offered a congratulations by recruiters at JPMorgan Chase at graduation). But it’s possible to spend a lot of time Snapping with friends before seeing anything that looks like an ad.

Still, many advertisers are eager to work with Snap. “Last year 75% of every ad dollar was going to Facebook or Google. As an independent publisher, that makes me shake in my boots,” says Shane Smith, CEO of Vice Media, which has a Snapchat Discover channel. “Advertisers have to park money at Snapchat. If they don’t, they are subject to the duopoly. Anybody who understands how advertising dollars work on the web knows that Snapchat mathematically has to be successful.”

And Facebook is finally showing its age. “On Facebook’s Newsfeed, all of a sudden you have your great-aunt fighting with a neo-Nazi that found you by accident. It goes not just to your friends but to your friends of your friends,” says Ryan Broderick, the 27-year-old deputy global news director at BuzzFeed. “If they don’t continue to evolve and stay ahead of Snapchat, Facebook might be something people use but don’t care about. It could end up looking like the New York City subway system, this thing you don’t want but you have to use.”

Facebook has tried to replicate Snapchat several times. In 2012, it created an app called Poke, which didn’t take off; in 2014, it tried Slingshot, which did just as badly. But in August, Instagram, which Facebook owns, launched its identically named, identically disappearing-after-24-hours Stories section. More than a third of Instagram’s 400 million daily active users are posting on it. It’s likely the cause of Snapchat’s slowed growth in the fourth quarter of last year. As Snap’s prospectus warns, “This demographic may be less brand loyal and more likely to follow trends than other demographics.”

Meanwhile, Snapchat has given advertisers a place to drop old-school, mass-marketed commercials in its Discover section, in which media companies are creating very short videos. The Washington Post, CNN, the Economist, the NFL, E!, Vice, Vogue, Comedy Central and brands owned by TIME’s parent company, like People, are all producing videos shot vertically to fit the phone. Saturday Night Live seamlessly stitched together a series of short videos to tell the story of liberal Brooklynites panicking as they try to boycott every product with ties to Trump. (Just three years earlier, SNL’s Cecily Strong made this joke at the Consumer Electronics Show: “The founders of Snapchat last year turned down a $3 billion offer from Facebook and a $4 billion offer from Google. It’s a surprising show of integrity from the guys who invented the app that lets you look at pictures of boobs for five seconds.”)

Even if the Discover section doesn’t turn into TV for iGens, NYU business-school professor Arun Sundararajan thinks Snapchat has some advantages over other platforms, namely demographics. The users are a lot like his Snap-addicted 13-year-old daughter: they skew female (boys interact through online video games), young and rich, three traits advertisers like. And it provides the necessary function teens once got from a landline: a way to spend time with their friends when they’re stuck in the house with their families. The main thing that’s communicated on Snapchat is “here I am.” “It’s a stream of consciousness,” says Sundararajan. “It’s what people thought Twitter would be when it first came out.”

It seemed dumb to talk to Sundararajan when there was a 13-year-old right there in his home. So I had him put his daughter on the phone. “I text sometimes. But Snapchat is better. You can see if someone opened it and are ignoring you. On the snow day, everybody was Snapchatting what they were doing in the snow,” said Maya, whose Snapchat score–which is roughly the number of Snaps she’s sent and received–is nearly 45,000 (of these images, she’s saved about 100 to her permanent “memories” section). Maya has streaks with about 40 people, whom she Snaps twice every day just to be sure the streak goes on. She was pretty upset, since the day before her cousin had blown their 178-day streak.

So, in a weird way, Snapchat is the only social-media company, unless we now think socializing consists of yelling about politics, reading news and extolling your personal brand. Snapchat is about sharing who you are right now. And the most effective way to do that is by seeing each other. In a 1953 TIME cover story on the growth of amateur photography, fashion photographer Irving Penn said, “The photographer belongs to the age of the subway, high-speed cars and tall buildings. His picture is made to be seen amid the haste of contemporary life.” In other words, in a snap.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com