Sometimes a camera is more than a tool to document, it is a weapon of resistance. When Henryk Ross carefully recorded daily life at Lodz Ghetto from 1940 to 1944, he was defying a fascist regime with the unequivocal power of photography.

Today, more than 3,000 photographs and negatives – as well as collected historical ephemera – stand testament to the enduring scars of the Holocaust. A new exhibition at the Museum of Fine Art in Boston and accompanying book, both entitled Memory Unearthed, draw together this work and offer an extraordinary insight into the brutalities of ghetto life.

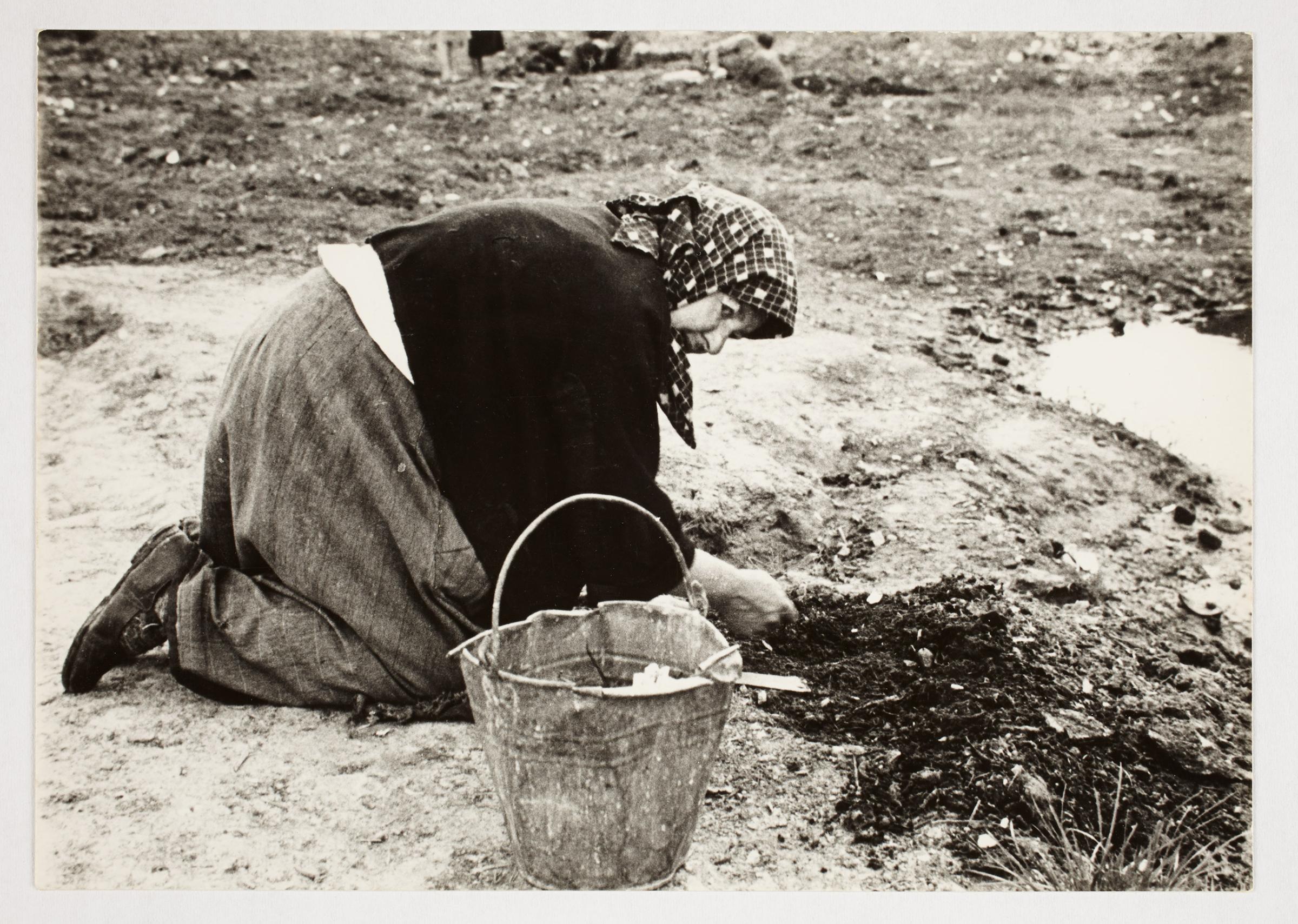

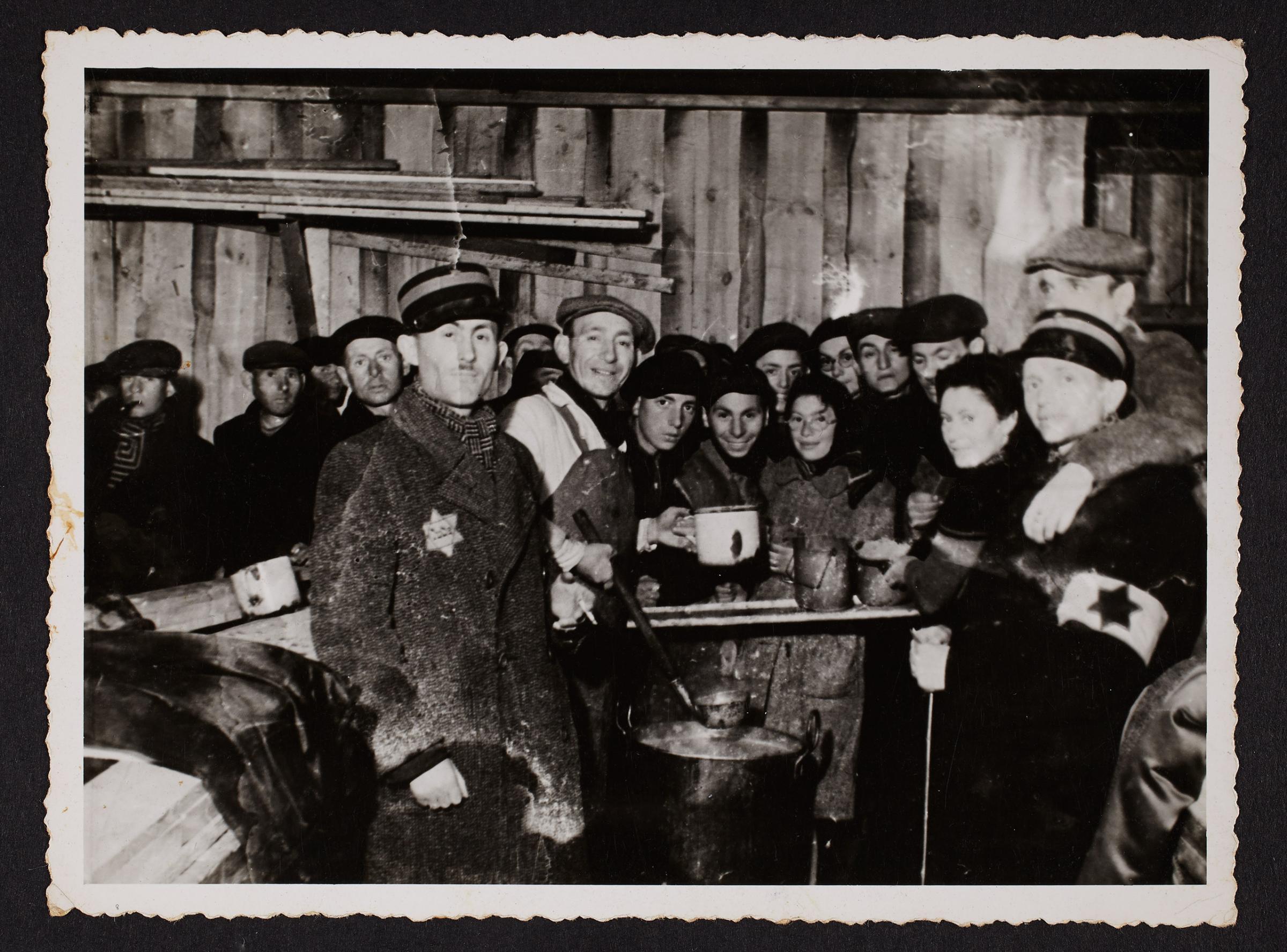

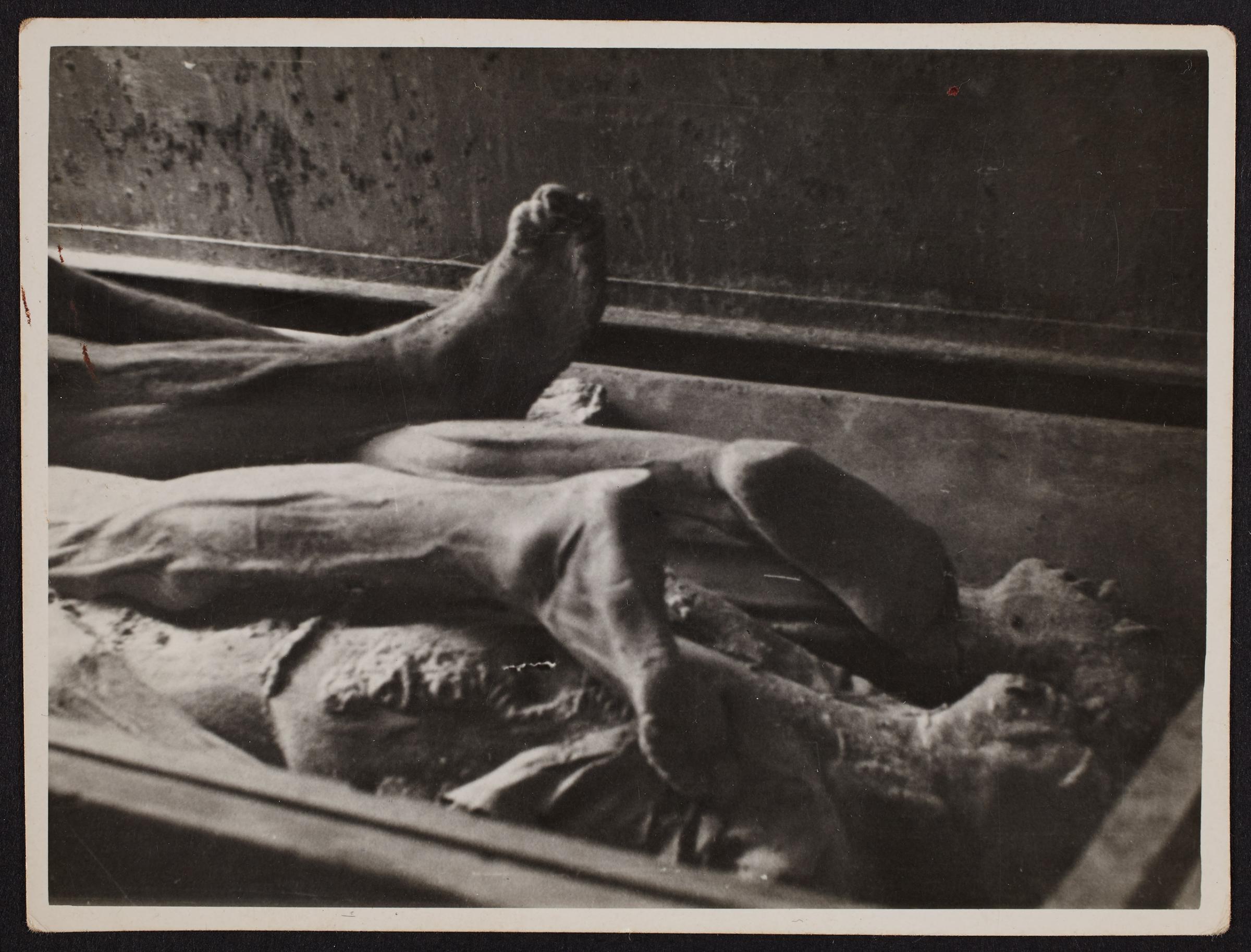

Ross took the images while working as a bureaucratic photographer for the Jewish Administration’s Statistics department after being confined to the Polish ghetto in 1940. Some images are commissioned ID cards or Nazi propaganda but many clearly are not. The contrast between the constructed formality of a smiling factory worker with the horror of human remains is palpable. Ross took the unauthorized images at great personal risk; through cracks in doors or a gap in his coat, he accumulated a record, a physical memory, of what he had seen and suffered.

The collection offers a rich tapestry of life at Lodz; revealing the horror but also the rare moments of joy. “The lighter moments are a real testament to the idea of survival and resilience,” Kristen Gresh, curator of photographs for MFA Boston, tells TIME. When our reference point is distilled to a few images of unimaginable human suffering, proffered by Hollywood or the media, it’s startling to see moments of ordinary life; children playing, families laughing and eating together, weddings. Gresh believes those lighter moments, likely taken between 1940 and 1942, demonstrate an attempt to live in normalcy as much as was possible. “Those moments help us to understand the complexities of life in the ghetto,” she adds.

The body of work is significant because of its incredible range and exhaustive chronology. It is also significant because it survived. Towards the end of the war, Ross and his wife Stefania, buried the negatives in sealed iron jars that were then placed in a wooden box lined with tar. They were recovered in the spring of 1945. “Given that Henryk Ross had the insight to bury all his negatives and prints and that he was a miraculous one of the eight hundred and seventy-seven survivors is remarkable,” says Gresh. “There are other photo documentations of different ghettos during the Holocaust but to have this in-depth view from one specific photographer is very rare.”

Not only is the collection revealing of daily life in the ghetto but one comes to understand Ross the photographer and Ross the man. He was an insurrectionist, quietly defying the fascist regime with a steady determination and honesty. He was painstakingly thorough, vigilantly observant and above all humanistic. “When you see all the photographs together, you see he was incredibly courageous,” says Gresh. “The fact that his photographs were used in the end in the Eichmann trial, also shows his own perseverance and commitment to making an historical record.”

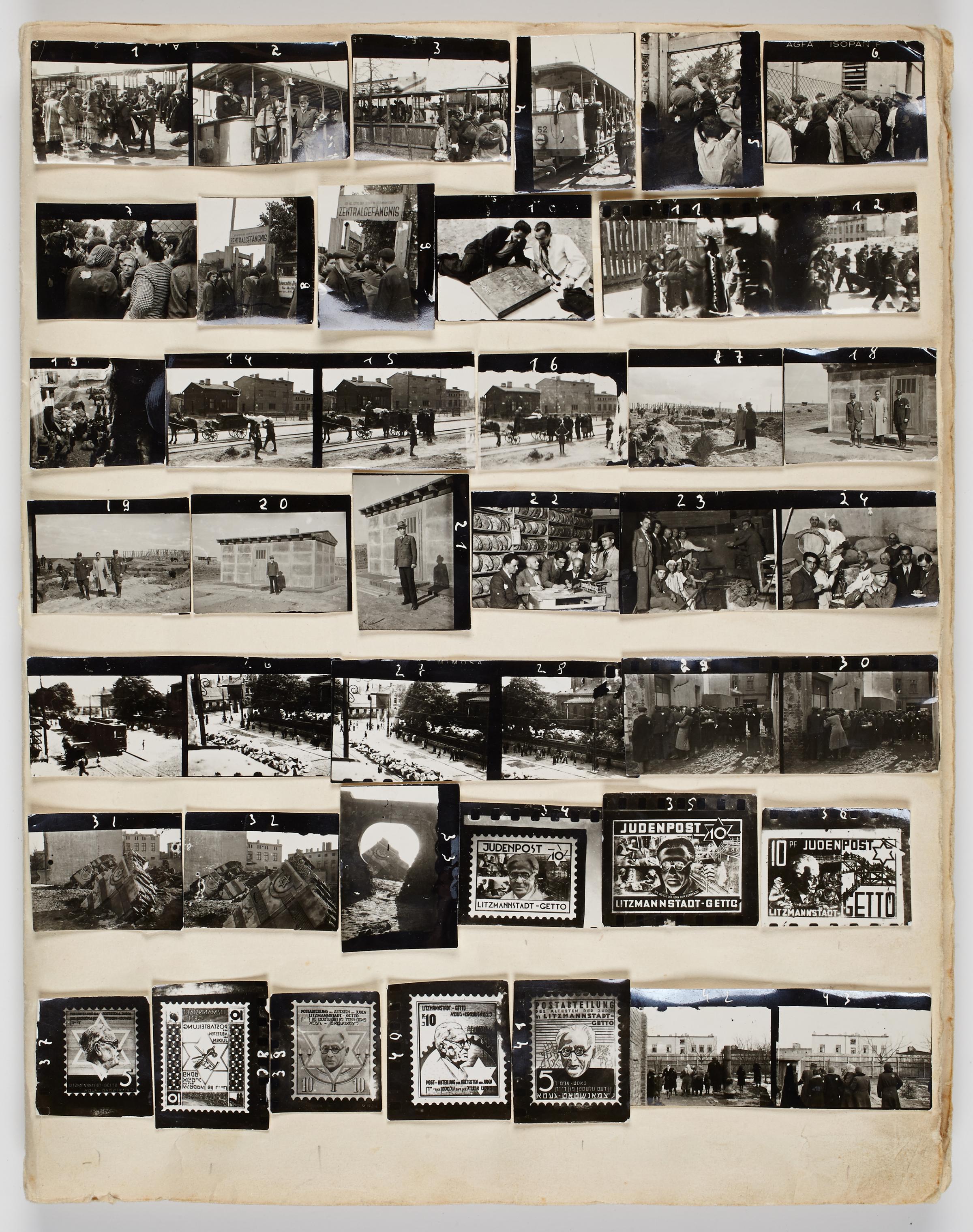

The centerpiece of the exhibition is a scrapbook of negatives put together by Ross towards the end of his life, many years after his liberation. The contact sheets are assembled in rows but not sequentially; the groupings jump between seasons and scenes. But Gresh believes we see another side of Ross again through this somewhat puzzling edit. “The album really shows the true voice of Ross because he’s the one that put them together,” she says. “The negatives are not necessarily coherent but there are smaller stories within and so you can see the different aspects of a survivor’s experience.” The editing process may also have a means to understand, years later, the enormity of what he had documented.

Kristen Gresh is the curator of photographs at the Museum of Fine Art in Boston. Memory Unearthed: The Lodz Ghetto Photographs of Henryk Ross is on display from March 25 – July 30.

Alexandra Genova is a writer and contributor for TIME LightBox. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram

Follow TIME LightBox on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com