Few are alive today who remember the 1948 Olympics in London. To commemorate London’s third hosting of the Games, TIME has traversed two continents to speak to the last surviving medalists from the U.K. and the U.S. for its special Olympics edition. Those competitors speak of feelings familiar to us all—the comfort of a lucky charm, the joy of victory. They also recount experiences that are foreign to many athletes today: the enervating effect of post-war rations, and training sessions fitted around everyday jobs.

Despite the various hardships they encountered, the athletes interviewed by TIME remember the Games fondly. Yet when the International Olympic Committee selected London to host the 1948 Summer Olympics, not everyone in the city was pleased. “The average range of British enthusiasm for the Games stretches from lukewarm to dislike,” wrote London’s Evening Standard in September 1947. “It is not too late for invitations to be politely withdrawn.” Even government officials who had pushed for a London Olympics acknowledged that following the devastation of the Second World War, Britain had few resources to spare for a sporting contest. “We have a housing shortage, and food difficulties, which do not permit us to do all we wish,” said Prime Minister Clement Attlee in a radio address welcoming athletes in 1948.

(For daily coverage of the 2012 Games, visit TIME’s Olympics blog)

It was called the ‘austerity’ Olympics—in a sense that even in today’s frugal times we can hardly fathom. With a budget of just $1.2 million (compared to today’s almost $14 billion), no new venues were built—instead, organizers made do and mended. The Henley Royal Regatta course hosted rowing events despite being 70 meters too short. Javelin throwers, deprived of stadium lighting, cast their spears in the dark, while judges officiated with flashlights. Wembley Stadium—usually used as a greyhound racing arena—received a new brick rubble cinder surface, which quickly turned to slush in the rain.

Yet, as Atlee pointed out, if there was anything lacking, it was not “good will.” Britain worked hard to be able to welcome 4,000 competitors from 59 countries – converting university dormitories, schools and RAF bases into accommodation for visiting athletes and their entourages. The army convalescent camp in London’s Richmond Park became an athletes’ village, complete with a ‘milk bar’, a cobbler’s, a hair dresser’s, a post office and a cinema to seat 500. Good will also streamed in from other nations, particularly when it came to food. The Dutch shipped over 100 tons of fruit and vegetables, Denmark contributed 160,000 eggs, and Czechoslovakia sent 20,000 mineral water bottles. The Brits cooked these and other contributions in camp kitchens, attempting to cater to national cuisines. Although post-war rations were boosted for athletes, the fare wasn’t always well received—legend has it that oarsmen displeased by their end-of-the-Olympics dinner at Henley began to chuck bread rolls in protest.

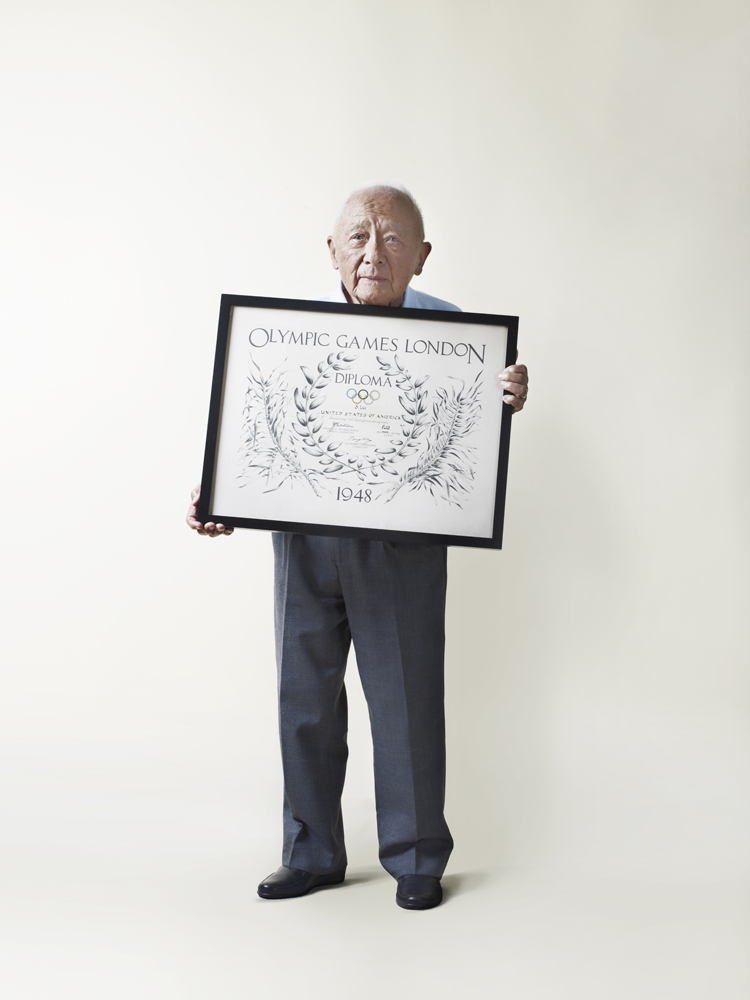

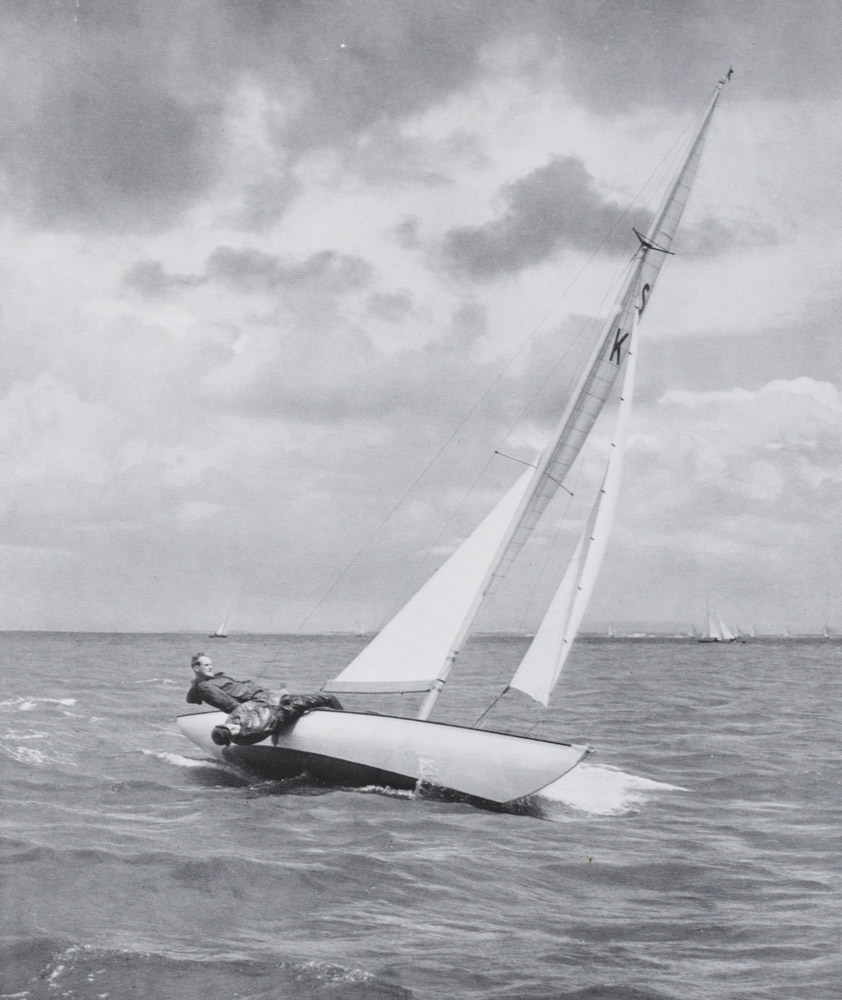

Still, athletes managed to enjoy themselves, without fine cuisine and—in many cases—without alcohol (though the French team carted over their own wine). After winning a gold medal in the swallow sailing class, David Bond and other competitors celebrated by going to a dance at the Imperial Hotel in Torquay, on the English coast. “We had a wonderful ball,” he tells TIME. “Nobody got drunk actually.” In 1948, the rewards for top competitors, were modest — a medal to show to their family and, in British cyclist Tommy Godwin’s case, a post-race glass of chocolate milk. There were no multi-million dollar endorsements, no spandex uniforms, no neon mascots. The big technological advances in 1948 were the photo finish and silk swimming costumes, which replaced saggy cotton. Yet for all the differences with the modern Games, some things have remained the same. Sixty years later, people from all over the world will gather once more in London to celebrate the Olympic spirit. Londoners will still grumble. And like Prime Minister Attlee said in his address, everyone will be hoping for a bit of good weather.

Jim Naughten is a photographer based in London. See more of his work here.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com